A Brief Guide to Worldbuilding (And Why It's Not That Important)

Lore can crush your dreams if you aren't careful.

"Worldbuilding" is one of those concepts that ebbs and flows in writing communities. It's a non-topic, and then suddenly it's the only thing anyone wants to talk about - and when worldbuilding is at its high water mark, there are resources in abundance to address it. There are checklists, map builders, podcasts, worksheets, books, and hundreds if not thousands of articles on this allegedly all-important topic. At times it seems like the only thing an aspiring novelist should care about.

So why add yet another how-to article to the pile? Well, this one's a little different. I think worldbuilding is one of the most overdiscussed and overrated topics in writing, and I'd like to tell you about its limitations.

I'm not going to tell you that the concept of worldbuilding is bad - there are people who think that way, who have strongly negative reactions to the very notion. I'm not quite there. Worldbuilding is not a bad thing, but it's also easily the least important aspect of the writing process, even in those stories where it really counts.

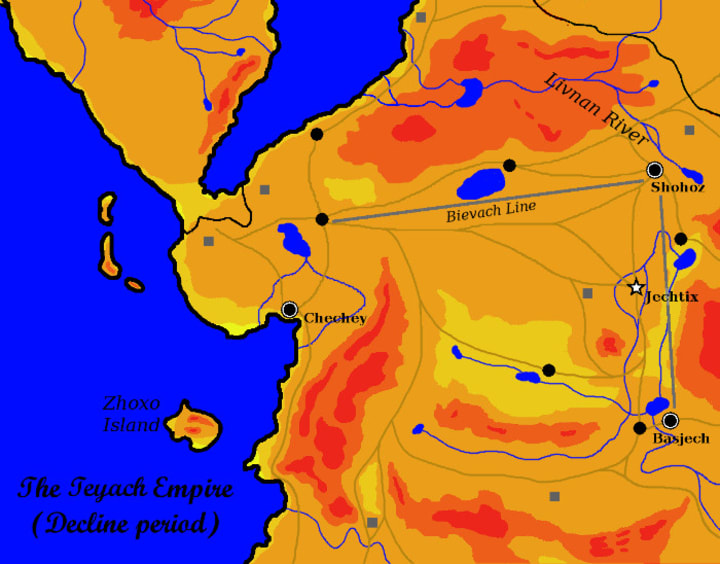

Now, I've more than dabbled in worldbuilding myself. Look through my works, and you'll find speculative stories like The Fabulist and All the Stars Within Our Grasp that take place in wholly fictitious settings. My current project - one I'm discussing here for the first time - is no different, and if anything is grander in scope than those earlier works.

Here's a simple map I worked up for the setting. I designed this before writing the first draft and it took a few hours. Obviously, I don't discount the importance of worldbuilding outright, but I take issues with the importance that many people place on it. This map ultimately doesn't matter, and here's why:

1. The background of a story is less important than the story itself.

If you've been reading articles about worldbuilding and are contemplating spending hundreds of hours on it, then you're planning something big. You wouldn't put in this much work for a one-off, so you're likely thinking a series - a trilogy at least, but more likely seven books, or twelve, or twenty. It means you're ambitious - good for you. And like anyone with ambitions, you're trying to think long-term. You want to lay down the groundwork for those twenty books you plan to write.

However, when planning long-term, it's still wise to remember what you need in the short-term. It does no investor any good to plan for the next ten years if he's going to be living on the street in a month. As someone planning a big novel series, you are making a kind of investment - in time, if not money - and like that would-be entrepreneur, you need to prepare for the short-term too.

Here's your takeaway: If you want to write and publish a big, genre-defining series, you first must write one single novel and at least one person must read that novel from cover to cover. If you never write that one novel because you get so caught up in writing lore that you never bother to finish it, or you do finish it but it's frontloaded with so much lore that no one bothers to read through it, then all of that work was for nothing. Remember, you're not writing Star Wars - you don't have an audience yet, so you'll have to win your readers over first.

2. Plan all you want, you'll still have to change things.

Let's move away from my current project and back to an older one, with an even less impressive map:

This is the map I set up for the serialized version of The Fabulist. I mentioned before that this version was loosely plotted so that I could steer it based on audience requests, but even then I still had a plot sketched out...a plot I had to change. Those of you who've read any version of The Fabulist may notice something missing: Middle Market. This was a location I'd planned for a possible follow-up book but was never intended to appear in The Fabulist. I pulled it out of my notes because I decided that the transition from the camps into Scrapland was too abrupt.

That was a major change to just one relatively short novel. How confident are you that your thousand-page story bible will survive to the end of a long series? Are you ready to invest weeks and months of your time even knowing that you'll end up shredding whole notebooks worth of lore that just don't work out?

3. Your readers won't notice anything that's not in the story.

Most of the people who fixate on worldbuilding are fantasy writers, and a lot of them came to fantasy through something other than literature. Some are influenced by video games, but the lion's share are coming from the world of tabletop RPGs. It's a cliche that every Game Master dreams of writing a novel about his campaign, and whether or not that's true (and it absolutely is), it's obvious that many would-be authors are current or former GMs.

That could be a good thing - running any kind of tabletop campaign will teach you a lot about the fundamentals of storytelling. On the other hand, it can also lead to a lot of bad habits. Some GMs-turned-writers keep thinking in terms of now-nonexistent mechanics and will try to "balance" characters as though they had stats. More relevant to the topic at hand, GMs are accustomed to working in settings with autonomous characters who poke their noses into the darndest places. They're expected to have a description for every object a player might pick up and an encounter for every location a player might visit. In short, they're used to working with open-ended lore rather than linear stories.

If you want to write a novel series, you're going to have to unlearn at least some of that. That first map, the one for the unfinished, unnamed project? You see all of those paths and cities and rivers and mountains? The readers won't be "exploring" most of those. The readers will be going exactly where I want them to, so making "content" for the other places is pointless for now.

Remember - in a novel, your characters have no autonomy and no one is going to accuse you of railroading because you didn't give them enough choices. Focus on the places that you will have your characters go - the places critical to the story.

4. You can always build the world later.

But what about those other places on the map? Surely they're not purely there for decoration? Surely there's something there? And what about everything else - the government, laws, religions, and cultures of this world? What about the history, and the future? Do we never plan for those things?

Of course we're going to plan for all of those things, but you've probably been doing that already. For if you are planning a big series, some twenty-book, two-million-word epic that will mark you as an heir to Tolkein, you've probably thought beyond the page. The end goal, of course, is the big-budget movie series that will bring your words to life. If you're at all media savvy, you've also thought of the intermediary products - the graphic novels, animated shorts, video games, board games, and other products that will extend your vision to new markets (and make a bit of extra scratch for you). Maybe you've even thought of your preliminary add-ons, the novellas, short stories and flash pieces that will help promote your novels in that all-important early phase.

Here's the trick: You can use all of those things to expand your universe. Short stories, side novels, and (down the road) comics and games all give you a chance to explore parts of your world that weren't featured in the novels. And the novels themselves? An outline isn't a bad idea - especially if you are literally planning to write twenty of them - but you can work on those later as well. You can plan for a certain novel or story to focus on a certain geographical region, an ethnic group, a span of history - but you don't need to figure out the details right now. You can do broad strokes now and go into detail when it matters.

That's the other takeaway, maybe more important than the first one. You are not obliged to build an entire world all at once. If you're planning to work in this setting for five years, ten years, twenty years, then you have plenty of time to get into the reeds and make it come to life. Don't knock yourself out now, especially if you haven't even written the first manuscript.

Or, at the very least, don't explore the world until you're sure that you've slain all of the creative dialogue tags in it.

About the Creator

Andrew Johnston

Educator, writer and documentarian based out of central China. Catch the full story at www.findthefabulist.com.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.