The Penlee lifeboat disaster, 1981

All lives were lost during a terrible storm in Cornwall

The Penlee lifeboat disaster of 19th December 1981 brought home to everyone who sets sail around the coasts of Great Britain just how much we owe to our lifeboat crews. They are all unpaid volunteers whose equipment is paid for entirely by public donations. They give their time, and sometimes their lives, in selfless devotion to their fellow seafarers.

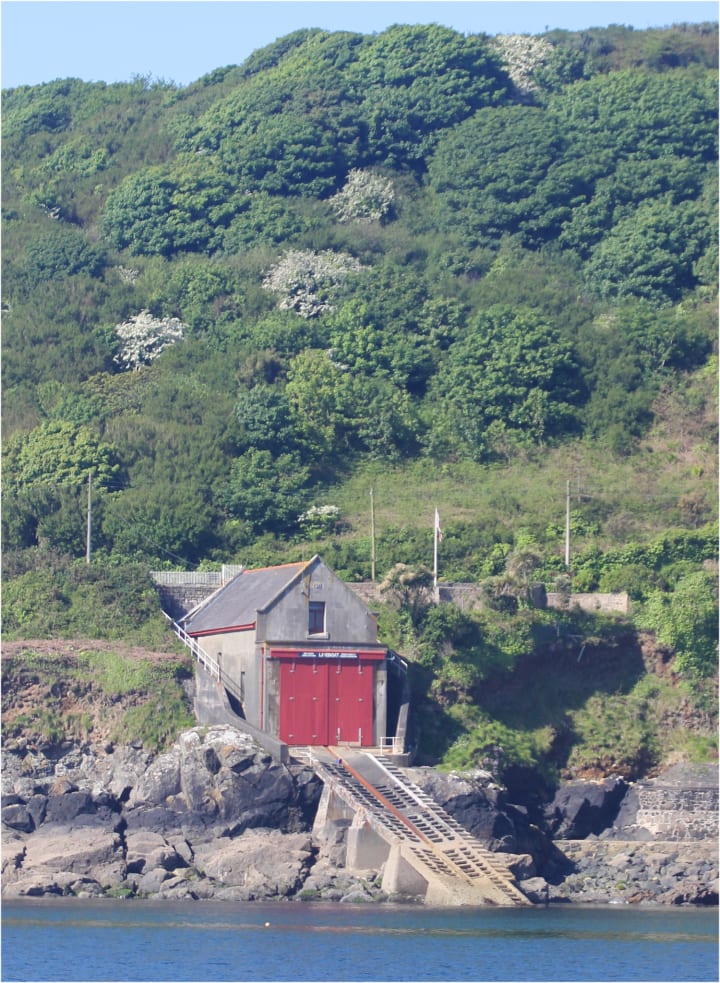

The Penlee lifeboat

Cornwall, at the south-west corner of England, juts out into the Atlantic, attracting the worst of the weather and the massive breakers that crash against its granite cliffs and rocks. It is not surprising that there are no fewer than fourteen lifeboat stations around the coast of this one county alone.

Penlee Point is just to the north of the fishing village of Mousehole (pronounced Mousle to rhyme with tousle). The first lifeboat was stationed here in 1913, transferred from nearby Newlyn, although there had been a rescue service in the area from as far back as 1803. In the years before 1981 the station distinguished itself by carrying out many operations and saving lives, recognised by the award of many medals and certificates.

In 1981 the station was equipped with “Solomon Browne”, a 47-foot Watson class wooden boat, a type that has long been superseded. However, it was highly manoeuvrable and could be launched straight down a steep slipway into St Mount’s Bay.

The voyage of Union Star

Union Star was a small bulk carrier, registered in Dublin, that was making its maiden voyage from Denmark via the Netherlands to Ireland, with a cargo of fertiliser. The master was Henry Morton, who had a crew of four on board, plus his wife and her two teenage daughters. He was breaking the rules by having family members on board, but that is a rule that is often broken.

Weather conditions were bad as Union Star beat her way towards Lands End, hoping to make it round the headland and into relatively calmer waters before the worst of the storm struck. However, Captain Morton’s luck ran out when his engines failed just as he reached the most exposed part of the voyage. He was offered a tow from a tugboat, the Noord Holland, but declined the offer. By riding out the storm at anchor and repairing the engines in calmer weather, he would avoid having to pay salvage charges.

The storm was one of the worst to strike that part of the coast for years, with winds of 85 mph, gusting to 95 mph, which is hurricane force. Union Star started to drag her anchor, and the fuel tanks became contaminated with seawater. The ship was being driven towards the Cornish coast and had no means of avoiding her fate if the storm continued, which it did. The Noord Holland was still in the area, should the captain change his mind, but even this option vanished when conditions became so bad that the tug itself would have been in danger. Eventually, Henry Morton called Falmouth Coastguard for help, and the call went out to the Penlee lifeboat crew.

The launch of Solomon Browne

When the call goes out, a lifeboat crew stops what it is doing and gets to the lifeboat station with all due speed. All the crew of the Penlee boat lived in Mousehole, some of them being local fishermen, and some with other jobs. They included the landlord of the Ship Inn, for example. That night, most of the crew were socializing in the British Legion club in the village, but, knowing that they were on call and also being aware of the state of the weather, they would have kept their alcohol intake to a minimum.

The Coxswain was William Trevelyan Richards, at 56 a highly experienced lifeboatman who already had commendations for bravery for previous rescues. Richards knew that this was going to be a very dangerous mission, and for that reason he refused the services of Neil Brockman, aged 17, because his father was already in the crew, and the Coxswain would not risk the lives of two members of any one family. This is common practice in the lifeboat community. The lifeboat was launched shortly after 8pm, well after dark, into waves that reached as high as forty feet.

Solomon Browne did not have far to go to find the Union Star, which was approaching the rocks close to Boscawen Bay and the Tater Du lighthouse, only a few miles down the coast. A helicopter from the Royal Naval Air Station at Culdrose was overhead, but conditions were so bad that it was impossible to winch anyone off the ship. Eventually the helicopter had to break off, and so did not witness the final outcome. There were also people on the cliff top, but in the darkness they could see very little apart from the lights of the two vessels.

Tragedy strikes

In those tumultuous seas, and in the dark, it was essential that nobody went into the water, as their chances of survival would be virtually nil. Solomon Browne therefore had no choice but to get alongside Union Star and for the crew and passengers to be helped across on to the lifeboat. Coxswain Richards was in radio contact with Falmouth Coastguards, and we know from the radio transcripts that several attempts were made get the two vessels as close as possible. On at least one occasion, it would appear that the lifeboat actually landed on the deck of the coaster and was then thrown off again.

We know that four people did manage to get aboard Solomon Browne, as Coxswain Richards’s final message was “we’ve got four off at the moment”. Exactly what happened next must be conjecture, because no more was heard from the Coxswain, and the watchers on the cliffs saw no more lights from shortly afterwards. Nobody from either vessel survived.

A huge rescue mission was launched, but nothing could be done. Other lifeboats were called out, but the Sennen Cove boat could not get round Land’s End, and the Lizard boat, from the other direction, only found wreckage when it arrived. Only eight bodies were ever recovered, four from Union Star and four from Solomon Browne. Union Star lay capsized at the foot of the cliffs for several days before she broke up, but little was ever found of Solomon Browne.

The aftermath

So what happened? It is highly unlikely that the lifeboat capsized, because all lifeboats of its class were self-rightable. However, if a huge wave had turned the boat over, would all of its crew have been washed over the side? Or was one more collision between the vessels too much for Solomon Browne’s wooden hull?

Whatever the cause, the result sent shockwaves through the whole country, which had been looking forward to Christmas and was suddenly reminded of the perils faced by seafarers and the courage of those who volunteer to save their lives.

The shock was particularly profound among those people whose living is made from the sea, and the entire population of south-west England. The custom at Mousehole itself has been, on the evening of 19th December every year, to extinguish all lights in the village as a mark of respect.

A local appeal raised three million pounds to support the families of the crew and provide fitting memorials, although many contributions came from well beyond the local area.

There are always “might have beens” that are asked on such occasions. Should Henry Morton have been required to take a tow from the Noord Holland? One consequence of the disaster has been that, in similar circumstances, today’s regulations demand exactly that. Had Morton’s three family members not been on board, would Solomon Browne have needed to make another attempt to get alongside? Perhaps so, given that only four people had been rescued and not five, but would it have been easier to rescue five seafarers rather than eight people who included two teenage girls? Such questions can be asked, but probably not answered.

There is still a Penlee lifeboat today, although the old lifeboat station is no longer used, being instead preserved as a memorial to Solomon Browne and her crew. In 1983, an Arun class lifeboat, the Mabel Alice, came into service, based at Newlyn. In 2003, a Severn class boat, the Ivan Ellen, came into service. Both boats have made many lifesaving rescues in recent years, including some that have earned awards for courage and outstanding service.

The full list of the lost crew of Solomon Browne, all of whom received posthumous awards, is as follows:

William Trevelyan Richards (age 56) (Coxswain)

James Madron (35) (2nd Coxswain)

Nigel Brockman (43)

John Blewett (43)

Kevin Smith (23)

Barrie Torrie (33)

Charles Greenhaugh (46)

Gary Wallis (23)

In 1992, Neil Brockman, who at 17 was refused a place aboard Solomon Browne on the night that his father lost his life, was appointed Coxswain of the Penlee lifeboat.

I grew up in Poole, which is where the Royal National Lifeboat Institution has its headquarters. I have known many men and women who have gained their living or recreation from the sea, and some who have been members of lifeboat crews. I am delighted to have this opportunity to pay my own tribute to the selfless dedication of these volunteers who put their lives at risk to help save others.

About the Creator

John Welford

I am a retired librarian, having spent most of my career in academic and industrial libraries.

I write on a number of subjects and also write stories as a member of the "Hinckley Scribblers".

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.