Queer and Radical Women in the Third Reich

An exploration into the feminism of Germany's troubled past

Hearing little about the Holocaust from my German family and learning the majority from museums and books that showed the ugly truth, I felt an overwhelming sense of guilt around my German heritage. It was a difficult thought process to acknowledge that my ancestors were most likely complicit, if not perpetrators, in the systematic murder of millions of Jewish, queer, Romani, and other oppressed peoples. I sought some sort of remedy for these dissonant thoughts; being ashamed of my lineage while also holding so much love for my family, their culture, and the country I come from.

I found solace in the story of Sophie Scholl and the White Rose, a student-run protest group that spoke out against Nazism during the Third Reich. Her public opposition to Nazism, her encouragement of other young people to stand in solidarity, and the persecution she faced from the Nazi government, spoke to what I had been searching for: a German woman to admire. I began to wonder about other radical women who would have spoken out against the injustices of Nazism at the risk of endangering themselves and their loved ones. Becoming more comfortable with my queer identity and recongizing the long-standing history of women like me, opened up a new area of interest. I had heard so often of the homosexual men that were also taken to concentration camps and the pink triangles they were besmirched with. I wondered what, if anything, was happening to queer women. I wondered if women were persecuted for the sole reason of being queer and not because of their intersecting religious or ethnic identities. Where did they go? What did they face? If I had been born a century earlier in Germany, would I have been exiled, repressed, or killed?

In constructing this archive, I hoped to tell a story that combined the voices of women who were given platforms to share their experiences and the vast majority of queer and radical women who were simply marked as “asocial” and often met their fate in concentration camps. I attempted to use both perspectives to show the disparity between the different ways queer women experienced the Third Reich. Erika Mann, Kaethe Kollwitz, and Clara Zetkin were all well-known figures who used their platforms as authors, artists, and political figures to speak against injustice and fascism. Their works were instrumental in filling the gaps left by the murder and silencing of so many other women. Radical groups like The Kreisauer Kreis and the White Rose fought back in radical ways that often resulted in execution. My archive does not tell the whole story, but includes a variety of perspectives that may not be found in another person’s interpretation. My primary focus of German women is also, I feel, underrepresented in the history of the Third Reich. While the German people were (rightfully) held responsible for the horrors of the Holocaust, the entire population is often painted with a broad brush as “bystanders”. In creating my archive, I hope to allow the voices of these activists to be heard once again, to remind us of the ways that complacency was not the only option.

Historically, as women are oppressed, their labor is exploited and their bodily autonomy is removed. This is true for Nazi Germany, not only through the forced sterilization of women from "undesirable" populations but for the encouragement of progeny among Aryan women. Women have attempted to retain bodily autonomy through the use of abortifacients and infanticide, as we have seen in writings like Bahadur’s Coolie Woman and Mies’ “Social Origins of the Sexual Division of Labor”. Nazi propaganda often discouraged these methods of family planning, depicting mothers, children, and Aryan families in an attempt to encourage women to take on the role of motherhood and continue the Aryan race. Various laws enacted by Hitler prevented women from pursuing white-collar careers, as well. This further encouraged women to remain in the domestic sphere. German women resisted this position in many forms. In Gupta's "Politics of Gender '', the author writes, "Working class women slowed down on the job, middle-class women could not be mobilised in the workforce. Most women refused to have large families. Whatever the motivation, personal or political, women's recalcitrance hindered the smooth functioning of the war machine and made it impossible to achieve a total mobilisation of 'Aryan' labour for total war" (45). Women relinquishing bodily autonomy and doing whatever they could to disrupt the spread of Nazism is radical in its own right. This quote from Gupta helps us to better understand the truth of resistance and complacency in Nazi Germany. Though many were complicit as Hitler terrorized millions, the country was not idle out of ignorance, but mostly out of fear. While these small acts of resistance were important in combatting fascism, the threat of Nazi persecution prevented many women from taking further action.

Many, but not all. Activist groups during the Third Reich were primarily organized by and composed of German men with political clout. This restricted women from being involved unless they were behind the scenes. The Kreisau Circle (a pun in German, The Kreisauer Kreis) was one of these activist groups that was predominantly male in its membership. The group was composed of German dissidents who had experience in the military and politics and was founded by Helmuth James von Moltke. In Alison Owings’ book Frauen, she interviews von Moltke’s wife, Frau Freya von Moltke. Freya was less involved in the Kreisauer Kreis than her husband, but took it upon herself to be involved for reasons of justice. Almost forty years after her husband was executed by the Nazis, von Moltke states, “"[T]he treatment of the Jews and those whom Hitler considered inferior. They were human beings like us, and the treatment contradicted what we thought civilization stood for. We found it a treason against humanity, as humanity had been taught to us. And we had personal ties to Jewish human beings. Many Germans did not. For them everything they heard was... theory. For us, it was our own skin. Those were our friends. Then it's very simple to be in opposition" (Owings, 249). Sophie Scholl, a founder of the White Rose student group, shared a similar sentiment and faced a similar fate to Frau von Moltke’s husband. In 1943, Sophie and some other students were arrested for distributing leaflets on their college campus. They were arrested, tried, and executed within the same day. Scholl’s legacy is one of the most well-known stories of activism that remains fresh in the minds of many German women. Her story is the primary reason that scholarship on radical women exists.

Political involvement from women was less common throughout the history of the German Empire but the First World War inspired many to become more involved. The German Communist Party elected renowned politician Clara Zetkin to parliament shortly before the rise of Adolf Hitler. As National Socialism began to rise in Germany, Zetkin became more concerned about the future of her country. On August 30th, 1932 Zetkin publicly denounced fascism and blamed the cabinet of President Hindenburg during a meeting of the German parliament. She stated, “The presidential cabinet bears a great burden of guilt. It is fully responsible for the murders of the last few weeks, murders for which it is fully responsible through its abolishing the ban on uniforms for the National Socialist Storm Troopers and by its open patronage of Fascist civil-war troops” (Zetkin, 1932). Though Zetkin did not live to see Hitler’s Reign of Terror, her legacy lives on as one of the most influential advocates for socialism in Germany’s history. Many followers of the German Communist Party were charged with heresy and made political prisoners throughout the Holocaust.

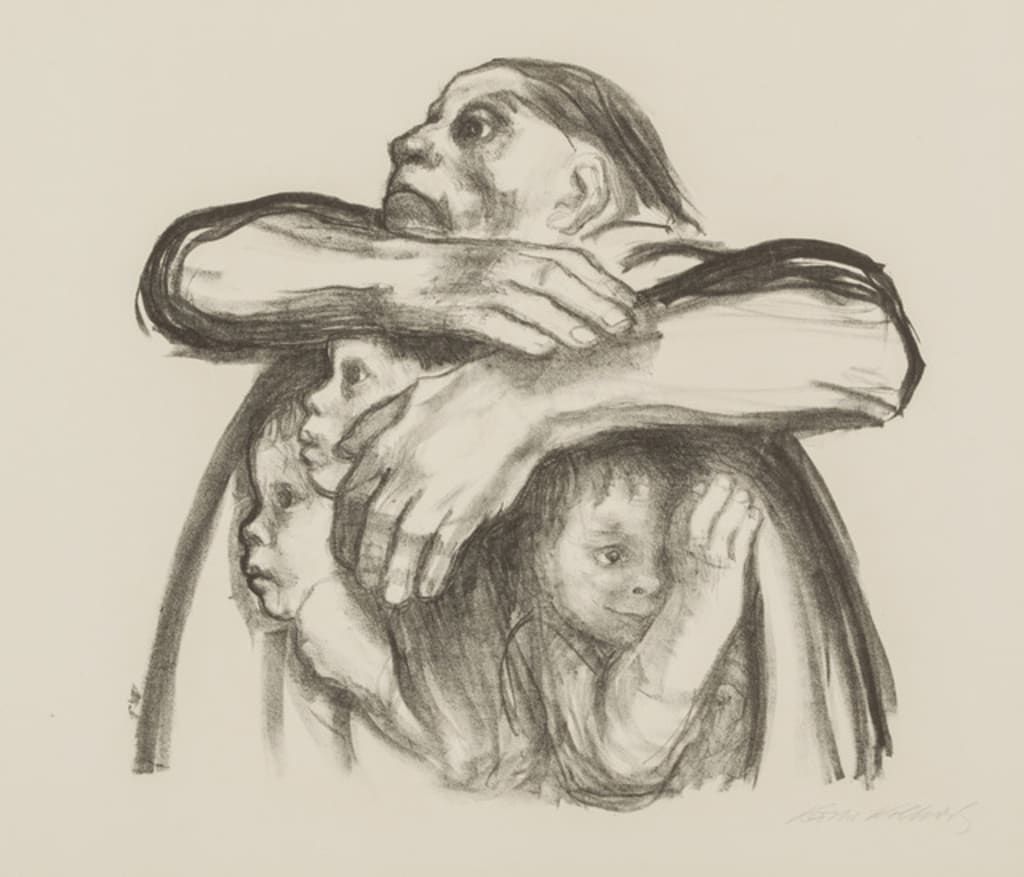

Other influential women used their written word and art to combat fascism. Erika Mann, the daughter of esteemed author Thomas Mann, was one of the most significant radicalists of the day. Not only did she engage in political theater performances with her brother and their friends, she also began to write and publish her thoughts on Nazi Germany. In School for Barbarians, Mann comments on the cruelty and indoctrination that was taking place in Germany’s schools. Systems like the Hitlerjugend and the League of German Girls were used to spread propaganda to the youth of Germany. Because of Mann’s critical stance and the privilege she had garnered from her father’s success, she was highly targeted by the Nazi party. The Mann siblings were nearly executed multiple times and were forced to flee Germany. Another German artist, Kaethe Kollwitz, was known for her lithographs and sculpture work. She had become famous during and after the First World War when she lost her son in battle. Her grief remained an inspiration for her art for the rest of her life. Kollwitz was highly critical of the war in Germany and used her art to make her stance known. In one of her last pieces, Seed Corn Must Not be Ground, Kollwitz depicts a mother shielding her sons from the war, hoping that they will remain young and innocent. Kollwitz was removed from several artist groups and institutes because of her support for left-wing parties such as the German Communist Party.

Both Mann and Kollwitz, in their personal writings, have identified themselves as queer. The intersectionality of their identities as women, queer individuals, and anti-fascists were factors in their acts of resistance. Other queer women, unfortunately, were not as lucky or as privileged as these two radical artists. Though lesbianism was never a crime in Germany, many queer women were accused of other crimes so the Nazi party could formally persecute them. One of the most common codes that queer women were found guilty of was § 183a. Public nuisance. The code reads, “Anyone who publicly engages in sexual acts and thereby deliberately or knowingly causes a nuisance is punished with imprisonment for up to one year or with a fine if the act is not punishable in Section 183” (91). Though one year of imprisonment was the norm before the Third Reich, under Hitler a violation of this section could be grounds for internment in one of Germany’s work camps. Queer women were most often forced to wear the black “asocial” triangle rather than the pink triangle that indicated a homosexual man and were sent to women’s camps like Ravensbrueck.

These areas of scholarship have vast silences, similar to the ones that Narrative Psychology and Storytelling has explored throughout the Spring Quarter. In Mushaben’s “Memory and the Holocaust” (2004), the author writes, “The memory of the Holocaust has never been confined exclusively to Germany or Israel, but it has been confined largely to experiences, perceptions and theoretical frameworks defined by men” (149). This is similar to so many histories that have fallen into the hands of the hegemonic few who controlled record-keeping. As we’ve seen in the writings of authors like Gaiutra Bahadur, women rarely get a say into how their stories are told. This experience is not limited to times of indenture or slavery where women may not have been able to read or write down their own stories, we see this up until recently as documented in the Lesbian Herstory Archive. The same gaps in narrative exist within women’s Holocaust experiences. To this day, we have very little understanding of the lesbian experience in Nazi Germany. This is best depicted in a quote from Samuel C. Huneke’s “Duplicity of Tolerance”:

The question of whether lesbians faced systematic persecution in the Third Reich is still an open one and historians have been hard-pressed to find sources to answer it. The situation is not one unique to the Nazi period. Lesbians are among those most silent in the archive, their voices muffled by centuries of both oppression and apathy. Women’s long standing socio-sexual repression in Western European cultures in particular has led to a dearth of written evidence of lesbianism. Though most medieval and early modern European states technically outlawed lesbianism, courts rarely prosecuted cases of female homosexuality out of a more general disregard for women’s sexuality (p. 31).

This quote describes the issue in its totality. Not only were women’s voices left unheard, but their sexualities were disregarded. Because of the way that reproductive labor was violently reinforced, even on women who self-identified as queer, lesbian women posed less of a threat to reproduction than homosexual men. The Lesbian Herstory Archive touched greatly on the ways that queer women have been underrepresented historically, not only because they had little control over whose stories were told, but because of misogynistic and homophobic backlash that has rendered them silent. This seems to be the case of the Third Reich, as well.

Through constructing my research and compiling my resources I have felt a deeper connection to my culture, my queerness, and my ancestors. Acknowledging these radical and queer women has felt liberating, not only for them and their memories but for myself. The silences in these narratives were not only created through lack of attention but through the systematic oppression, exiling, and execution of these women. Hitler’s reign and the rise of fascism in Nazi Germany have not only created a scar on the face of Germany’s history but have left a lasting wound on humanity’s existence. A multitude of narratives were lost, agency and autonomy were revoked, and lives were torn apart. It is through the retelling of these women’s stories and the documenting of their lives (and the lives of those who oppressed them) that we best remember and understand both the resilience and the great injustices that humans are capable of.

References

Bohlander, M. (2010). German Criminal Code. Retrieved May 29, 2021, from https://adsdatabase.ohchr.org/IssueLibrary

Gupta, C. (1991). Politics of Gender: Women in Nazi Germany. Economic and Political Weekly, 26(17), WS40-WS48. Retrieved May 29, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4397988

Huneke, S. C. (2019). The Duplicity of Tolerance: Lesbian Experiences in Nazi Berlin. Journal of Contemporary History, 54(1), 30–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009417690596

Johnson, E. (1997). Gender, Race and the Gestapo. Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung, 22(3/4 (83)), 240-253. Retrieved May 29, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20756167

Mushaben, J. M. (2004). Memory and the Holocaust: processing the past through a gendered lens. History of the Human Sciences, 17(2–3), 147–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952695104047301

Owings, A. (1993). Frauen: German women recall the Third Reich. Rutgers University Press.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.