Livin' On The Rim

Slave descendants on a Georgia Plantation

Author's Note:

In 1973 I heard that descendants of plantation slaves were still living on a plantation near Waynesboro, Georgia. Caldwell and Bourke-White started their epic "You have Seen Their Faces" in Waynesboro. The story documented the plight of poor whites across the south. When I read it, I was astonished even back then that poor African-Americans had been completely ignored - a story even more compelling than that of the benighted whites. So I went down to the Carswell Plantation and found several dozen slave cabins still occupied by the descendants that had served the Carswell family over centuries of slavery. The story that follows is what I came back with. I sent it to an Editor at the Atlanta Journal Constitution. Never recieved a reply. A few months later the newspaper published a story by one of its own reporters - documentating exactly the same conditions on a plantation in Alabama.

Of Bonds & Bondage:

It is the country of Caldwell. It is the place where "dirt poor" became part of the language and where, for the better part of three centuries, the only living has come from the land. It is fertile here, a place called Burke County, Georgia. Sometimes it seems as if only the seasons change. The Loblolly pines cast an evergreen dark divide across the horizon from biting winter to steaming summer. They fill the air with an eternal, magical, and always far distant lambent blue mist.

A man called Samuel Eastlake came to this spot in 1767 with a land grant from England’s King George the Third. He named it Bellevue and, like many elsewhere before and after him, set in motion the bittersweet saga of the southern plantation.

The shadow of slavery is forever cast across such spots as this. For many, the story of such times is a simple one, an issue of right and wrong that condemns the white planter class. The truth is far more complex. It tells of both bonds and bondage, for the relationship between the Europeans and the Africans and their descendants was not only master and slave, but sometimes also patriarch and family.

I first came upon Bellevue deep into the winter of 1973. The fields around Eastlake’s great plantation house were bare. A chill Canadian clipper stirred dust devils against the sun-bronzed boards of the old plantation store as I loaded my camera. Across the barren field I could see the object of my journey down from Augusta, Georgia. A row of tumble down homes, the remains of slave shacks under the shadow of the great house. Not empty shells these. The shacks were still occupied by the descendants of those Africans who long ago left the Dark Continent to toil in the fields of Dixie. In those days I thought of ‘slavery’ as many others still do. What I heard about Bellevue had challenged these simplistic notions. Now I had come to see for myself.

I walked down the dusty track between the shacks. Youngsters from five to thirteen quickly gathered around friend John Fleming and me. Our camera bags, film and lenses were quickly dispersed among ‘assistants’ who insisted on carrying something. The shacks were amazing affairs. They were the original buildings, built sometime in the nineteenth century, perhaps as far back as 1835 when the first Carswell married Eastlake’s daughter. They were better slave shacks than were common for the times, built up off the ground, a brick chimney on either end with a dividing wall in the center. Some plantation slave quarters had plain dirt floors and chimneys made of wood lined with clay. In the old days two families would live in each shack, there had been at least ten families living here at Bellevue.

Over time the chimneys began to lean and even the heart pine boards succumbed to the harsh extremes of Georgia’s weather. The shacks all leaned one way or the other, the walls showing the efforts of the occupants to ward off the invasion of the elements any way they could. One had an old Texaco gas station sign bent around a corner where the rain, born on a north winter wind had rotted out several boards. Another was patched with particle board that was now sprouting a heavy coat of moss.

I stopped opposite a well, a hole in the ground boarded off with scraps of planking. Inside it a rusting chain and tackle block held up a battered narrow well bucket that creaked in the chill wind.

The nearest door opened, framing a stooped old man with red, rheumy eyes and a crop of gray hair beneath a black baseball cap.

“Help you?” He asked, one hand steadied him against the door frame as the other gathered the neck of a sweater tightly to his throat.

I explained that I wanted to talk, maybe take a few pictures. The old man looked at me for moment or two, and then motioned me inside. The walls of the shack were thickly papered to seal out the chill, not with proper paper, but with picture pages from popular magazines. There were thousands of them, papered one over the other. A log of hickory burned in an open fire before two chairs. The old man sat down carefully. A woman sat in the other chair, an ancient rocker, a woolen cap pulled down tightly over her hair.

The man held out his hand and I shook it. “Sam Royal, this is Matilda, she does the talkin’.” Matilda looked at me and motioned to a kitchen chair with two cushions covering a frayed cane seat. I sat, and told them what I had heard about Bellevue.

“Yes. My daddy used to tell me that his folks could remember the slave days. Not that we was any field hands you mind. Our people always worked up the big house far back as we could remember. I worked in the fields some, but then I married my first husband and he was the butler so I did the gardening around the Big House.”

“Things got better when I married my first man. He was the butler for Mr. Carswell all his life. Remember we was both gettin’ old one winter when the mistress wanted to build a fire in every room of the big house. He carried wood to every fireplace, I think there was 26 of them! After that he came home here, laid down and had himself a stroke and died.

“Sam here was the next butler. I married him too! See, Mr. Carswell’s grandaddy had slaves to do his work for him on the plantation. We aren’t slaves anymore, but we still do the work, an’ we still live in these shacks. Seems things haven’t changed much around here after all.” Matilda said she was crippled now and did not move around much anymore. “Sam does mos’ of the cookin’ now. That’s how come we live next to the well. Sam cain’t carry the water too far. If you want more about how things are here, you should talk to Luella Dunbar down the street. She’s got real good rememberance...”

Sam Royal groaned as he lifted himself out of the chair. The late afternoon light was fading fast, the clear deep azure sky forecasting another clear, cold night. Sam lit a kerosene lamp with a shaking hand, closed the glass and turned up the flame. I shook his hand for the last time. Matilda stared at the fire and spoke to me without turning her head, “If you write my name anywhere in a story you write it Matilda ‘Scrappy’ Royal. ‘Scrappy’s’ what I learned to write in Mr. Porter Carswell’s Plantation School.”

“Yes Ma’am,” I promised.

I found Luella Dunbar in the next shack. She came to the door dressed in a skirt over a pair of men’s pants, two sweaters and a hat pulled down over a tightly wound bandanna. I told her I wanted to hear about her life, take a few pictures. She invited me in without so much as a question. Luella had electricity, so we sat in her kitchen beneath a bare bulb where the light was good.

I started by asking her about her early life.

“Before I lived here I was with my mother in another shack. I worked for the plantation overseer Mr. Ralph Elliot. Now he’s the Sheriff here in Burke County. One day my mother reached over the fire to get a pot of coffee and a coal fell and caught fire to her stockings and her dress. She fell over and had trouble puttin’ the fire out, she burned some of her toes right off. She was crippled after that and not long after they had to cut her leg off. She jus’ gave up after that and died. She never cried out once all the time she was burning. I always remember that. “In 1928, after she died, I moved into this shack here. I’m 69 now an’ I still saw my own firewood!” I asked where the firewood came from.

“From Mr. Porter Carswell. I’ve always worked for Mr. Carswell and he’s a fine man. He don’t charge us old people rent for these shacks an’ he sees we’ve good firewood to see us through the winter. That’s on account of how our folks were Carswell people during slavery days.”

I asked Luella what stories she had heard from those times.

“My folks didn’t talk much about what their folks said to them. Work was work and things didn’t change much except that even the people in the big house were poor after slavery. I remember my Daddy sayin’ as how his folks were tellin’ him they always went to church on Sunday with the master of the big house. Then, after slavery, the black folk went to their own church and the white folk went to their own church, and things was different between them.”

What about her own family? I asked, did she have any children and where were they now?

“Well, I got me a man I married when I was sixteen. I had three children and every one of them died when they were born. A woman down the street, she had 21 head, so she gave me two. I brought them both up. One of them, he is sanctified now, a preacher up in New York. He’s healin’ people up there an’ I don’t know but that I wish he’d come down here an’ heal me, ‘caus I’m gettin’ awful old.”

“What happens when you get sick, or need a doctor...?”

“Not much nowadays, you jes’ have to get better on your own! My sister, she was the witch woman here on the plantation. She helped the babies get born, made her own cures from things that grew around here an’ knew other ways to put a fix on things that went wrong. Witchin’ was something she learn from our mother. She would tell us both that witchin’ was something her people brought from Africa and that it was important to pass it on. I remember when I was 26 I bought a bottle of underarm deodorant, cost me half a week’s wages, two dollar and fifty cent. No sooner used it than I started coughing and caught a cold. My sister had my husband break the bottle and I got better right away.

“My sister died herself a while back an’ her shack is fallin’ down now. I still go by there whenever I can an’ leave a little somethin’ on her porch. Don’t want her spirit unhappy with me! Did I tell you about my teeth?”

I said no.

“Long after my sister died I stepped on a board an’ it hit me in the mouth. I was too afraid to go to the dentist they said worked on teeth down in the town. I got a hatchet an’ put it up against my bad teeth an’ then hit it with a hammer. That split them in two and I could pull the pieces out.” The kitchen window was covered with brown paper to seal it. I could see that light was fading fast and there more people to see. I asked Luella if any of the people here had been field hands in their time.

“You should see Millie Sapp. She worked in the fields jes’ about all her life.”

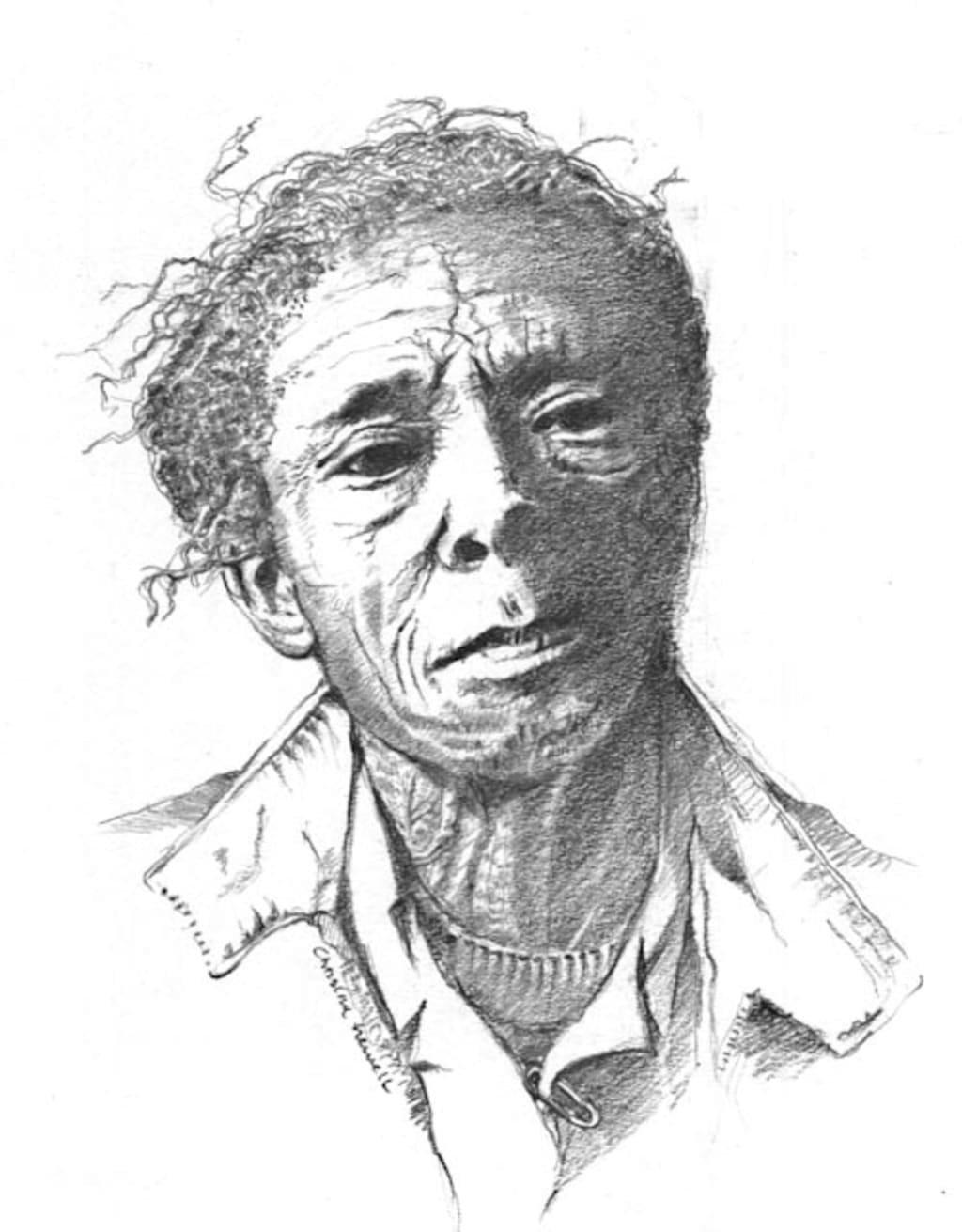

Millie lived in the one shack on the west side of the settlement street, just down from the well. I found her outside, bringing in an armful of split logs for the night. She listened to me, the dying sun casting a golden light and dark shadows across her deeply lined face. Her huge dark eyes surveyed me carefully. One corner of her mouth edged upwards in a half smile and she reached across and dumped the logs in my arms, opened the shack door and motioned me inside.

Millie’s granddaughter, Rosalee, was frying bacon on a skillet over the open wood fire. The walls, like the Royals shack, were thickly covered with newspapers. A kerosene lantern hung from a papered beam in the center of the room.

I said that I guessed life had been hard...

“I spent mos’ my time pickin’ weeds in the Summer and pickin’ cotton in the Winter. Lord, it was a happy day when machines learned to chop cotton! When I was born they jes’ put my name in the wish book. All these years I been wishin’ and never gettin’. All my life I’ve been livin’ on the rim.

“I was one of 14 children, got four years of schoolin’ at the plantation school, but the boys knocked me off my feet when I was thirteen and I had to quit school ‘caus I got a heavy stomach. I could sign my name, scratch out a few letters an’ maybe do a little figurin’.

I asked if things got any better in the summer.

She laughed. “Summer ‘round here the mosquitoes sing like a choir! I remember once when I went to the plantation store and bought me a can of mosquito spray. I bought it on time ‘caus I couldn’t afford to buy it all at once. Never did much good tho’. Never bought any again.”

She asked me to put one of the split logs on the fire.

“Mr. Carswell, he gives us the wood for free. Sometimes we have to split it ourselves, or pay someone fifteen dollars to split for us. ‘Bout one load heats the room for a week during the winter. I don’t eat breakfast in the wintertime, that way I don’t have to heat the kitchen.

“My folks? Well, they have always been Carswell people from the start. Me, I guess I’m Carswell people too. I’ve worked the fields on this plantation all my life and I have never been more than fifteen miles away from here since they day I was born. Guess I’ll die here too.”

I spoke to several more of the residents before the light finally gave way to the kind of star carpeted night you can only see from Georgia’s winter countryside. I met Mr. Porter Carswell on the porch of the Big House. We sat there for a few moments and talked about the past.

“I thought The War Between the States brought an end to the plantation system. Why is there this connection between you, here in the twentieth century, and the people who are descended from the slaves the War set free?”

He smiled patiently, as if once again another stranger was asking a question which words alone could not answer. He hesitated, then said it simply enough: “These people are descended from those who began working this land with Eastlake over two hundred years ago. They are part of our history just as we are part of theirs. No war brought down on us by Northerners, and no decree by the Federal Government can ever release us from the moral obligation we have to care for them as best we can. I can’t do much for them now, but I do what I can. Might seem strange to you after what you think you know, and what you’ve heard, but in a way, these people are family.”

I drove away from Bellevue, watching the bright lights of the big house flickering through the wind swept branches of the magnolias at its entrance gate. To my right the slave shacks seemed to huddle in the darkness, a dim light here and there, the rising moon catching the wafting wood smoke. Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke White wrote and photographed in Georgia for "You Have Seen Their Faces" long before I set foot in Burke County, Caldwell’s birthplace. They documented the poverty and prejudices of the South in a way that captured the attention of their generation. Yet right here, a scant few miles from Caldwell’s very own Waynesboro backyard, was a story he and Bourke White missed. Perhaps they had even chose to pass it by.

I found myself deeply touched by the dignity, the gentleness, and the hospitality of these slave descendants. Despite a crushing poverty unnoticed forty or more years after “You Have Seen Their Faces,” they maintained a sense of belonging to Bellevue, even a sense of loyalty. I later looked at the pictures Fleming and I had taken that day, Again I was struck by the smiling faces, by the expressions of simple dignity and character despite the years of hardship. Fleming and I went to Bellevue to document an example of extreme poverty in Erskine’s Burke County. Instead we were privileged to see the very last chapter of one saga of the many that make up the African-American experience in America. It had begun in 1767, and far from being ended in 1865, it was in fact playing out its last scenes within my own lifetime. As a freelance writer I have a real need to produce my work and get into the market place. The occupants of Bellevue’s slave shacks posed cheerfully for my camera, and gave willingly of their life’s experiences. Yet I felt uncomfortable with the story. I filed the pictures and my notes and decided I would revisit them only when I felt the time was right to tell the story. I thought a little time would help focus the remarkable experience I had recorded at Bellevue. In the years that followed I found other historic plantations in the South where slave settlements were intact. Many of them even housed the descendants of the original inhabitants. The more I traveled and recorded the South. The more I began to realize that there was for many years after the Civil War an unbroken bond between the families of the long gone great plantations and those of the slaves that served them. Until quite recently, it was always understood that the aged and the infirm could find a roof and some minimal support back on the plantation. Unlike Porter Carswell, most plantation owners I spoke to preferred to deny any such arrangement, but I found that it existed nevertheless. It was a vestige of the bond between planter and slave that flies in the face of accepted understanding of the relationship.

It was twenty-three years later when I went back the Bellevue for the second time. It was in the late summer, on one of those unusually cool afternoons when the air is fresh and free of the thunderstorms typical of the season. The barren field of years ago was covered in high corn. The corn stalks were surrendering their healthy green color to water short golden brown. The crop was dying. The once dusty street between the slave shacks was covered in thick grass. Vines and sweet grass were growing up around the weathered walls of the shacks. All were empty. The children were gone. Millie, Luella, Matilda and Sam, all the others I had met were gone too. They were part of the dust of Bellevue. Porter Carswell was gone too, the plantation house, for the first time since 1835, no longer carried the Carswell name.

I stood alone in front of Millie’s shack.

“I ain’t never sayin’ I had everything I wanted. But I am saying I’m happy.”

Millie’s last words to me echoed across the years, sounding like the last in a bitter sweet lament that began when a young English farmer came here to plant so long ago. Eastlake’s name was emblazoned on an historic marker the State had set up outside the great house. It seemed to me that the people I had met that cold winter day so many years ago deserved some small place in history too.

I drove home, took out my notes and pictures, and wrote these words.

-30-

Author's final word:

Fifty years later the words spoken above are still echoing in the back of my mind. I have never forgotten these people. Their fate and their story tugs at me still. Once, decades after my second visit, I had to go back yet again. This time the field where the shacks had once stood was barren. The remains of the cabins bulldozed, all signs of the past obliterated by weeds and wire grass. Old Mr. Carswell was long dead. His daughter married and went to Columbia SC. She would not take my calls. I guess she thinks this amazing past is dead, buried, and long forgotten.

About the Creator

Mark Newell

Mark Newell is a writer in Lexington, South Carolina. He writes historical action adventure, science fiction and horror. These include one published novel, two about to be published (one gaining a Wilbur Smith award),and two screenplays.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.