How do Ropes Work?

Hang about - it's not as obvious as it may seem - there is a twist in my yarn about the science

I use ropes every day because I live on a boat. And, even though we’re hauled out in the yard at the moment, painting while we live aboard, I’m still hauling them and tying them. Here’s a story about how they hang together.

Strength and build

When we’re afloat and I hoist the mainsail and harden up the halyard (rope) with a winch, I don’t know how much tension is in it, but the braided 13mm polyester is rated at about 10,000 lbs breaking strain. That’s a shade short 5 tonnes and I’m sure I don’t get anywhere near that or my sail would be torn apart.

Aside: For what it’s worth, sailors don’t usually use the word ‘rope’ — there are halyards, sheets, springs, hawsers and more, or just ‘lines’. Not ropes.

‘Braided’ is the way the ‘rope’ is woven and that’s what you see knotted around that lady’s leg in the image above.

There are other constructions, such as multiplait.

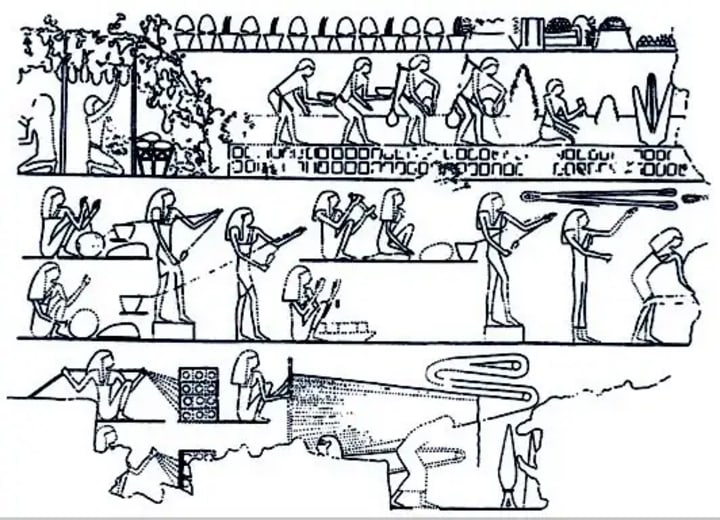

The ancient Egyptians were the first to document rope-making tools.

The old way of making rope was usually in three mains strands (sometimes four but multiplait also) and in many old dock areas you will see streets called ‘Ropewalk Street’ or ‘Ropewalk Road’ (as there was in the Welsh dock town I grew up in). In those streets the ropes were ‘laid up’ — that is twisted into shape.

Why all this intro?

Well, this morning I came across a piece of research about rope. Yes, I know not a word we sailors use, but these researchers are landlubbers. Excused.

It’s all about the yarn

This relates to the old rope constructions. Modern synthetic fibres can be spun endlessly, like politicians.

The actual strands of the natural fibre, sisal, are quite short, maybe a few centimetres. So how does a rope which is maybe 100 metres long actually work if it’s made up of such short strands? How can short strands of natural fibre make up a rope which holds tons?

Think about your mother knitting with a ball of wool. Sheep don’t grow wool 100 metres long. At least, not in Wales where I grew up.

The short fibres are spun into a yarn. Then to make a rope, the yarns are twisted into the final rope. Right hand or left hand twist (‘lay up’). ‘S’ or ‘Z’ as you look at the rope end-on.

An ancient puzzle

It is a mathematical puzzle that stumped Galileo, but researchers in France think they have discovered how rope and yarn fibres held together by nothing more than friction are able to carry heavy loads without breaking. Jérôme Crassous of the Institute of Physics of Rennes and Antoine Seguin of the Université Paris-Saclay have shown that small twists in a rope multiply into massive frictional forces that lock the fibres together. — Physics World

And here’s the twist

Following some rope-breaking tests, the researchers proved that it was the angle of twist relative to its thickness that determined whether the yarn would take tensioning without just pulling apart. They devised the ‘Hercules Number’ from a mathematical model, and it seems to predict a rope’s strength.

So, when the yarns are twisted and pulled the friction between the fibres gives the yarn its strength.

As the author of the article, Katherine Skipper, pointed out, it’s related to another interesting phenomenon:

It is nearly impossible to pull two interleaved phone books apart, the force pulling them together is strong enough to lift a car.

I’ll stick to hauling my halyards. I don’t need telephone directories. And anyway, who the hell has the time to actually interleave telephone directories? Imagine it. Get a bloody life!

You may be sleeping by now, but I had great fun pulling this all together and tying up the loose ends.

Knots

And then there are knots, lots of knots. You can’t have rope without knots. In fact the brilliant John Conway proved that there are only 9,582 types of knot.

Only.

There's a whole sub-branch of the mathematics of topology devoted to them.

I keep a few books handy and use probably half a dozen knots on a regular basis.

And here's a Monkey's Fist. And no, it's nothing to do with BDSM.

If you’re really interested in how ropes were made along Ropewalk Road then there’s a bit of old London history here [pdf].

And here's my story on Knots.

***

Canonical link: This story was first published in Medium on 6 April 2022

About the Creator

James Marinero

I live on a boat and write as I sail slowly around the world. Follow me for a varied story diet: true stories, humor, tech, AI, travel, geopolitics and more. I also write techno thrillers, with six to my name. More of my stories on Medium

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.