The Future of Invention in 1879

Concerns about advancement result in asinine advice

The Atlantic recently fully digitized their archive going back to 1857. This is an examination of one article from the August 1879 issue entitled The Future of Invention by W. H. Babcock to see the hopes and fears about technological change.

Overproduction & Underemployment

A concern of the author is that mechanization of labor is reaching a point of self-defeat. Modern machines can make products so easily with so little labor that we are going to have a world full of surplus consumer goods and unemployed workers. However, his ideas of surplus consumer goods seem quite quaint by todays standards "If hats become very cheap, a man may get a new one every month, instead of two or three a year; but no man can possibly need, or will buy, many more than the former number." The peak of consumer excess: a dozen hats. I went around my home and counted the number of hats and caps, there are 24. I'm not even a hat guy, I'm not that interested in hats.

Looking to the future, his concerns only heighten:

Suppose, for example, that the many attempts at producing a satisfactory traction engine should result in success; is it not evident that the number of horses in use would be greatly diminished? This would similarly reduce the demand for horseshoes, horseshoe nails, currycombs, and harness of all sorts, every one of which now forms the centre of extensive manufacturing interests, employing many men.

The idea of trying to stop the use of cars to save the horse and buggy industry is the ur example of short sighted decision making. For one thing Babcock was unable to foresee all the jobs that would be created manufacturing, maintaining and operating motor vehicles.

Though perhaps in some ways he was ahead of his time. Auto production has become highly automated. If fully self-driving cars are finally released into the world then truck and Uber drivers could see their work disappear. It is hard to see what jobs would come in their place.

Except that's simply taking too narrow of a view on work. The issue our age is not what to do with the glut of unemployed but a labor crisis (for industry).

Resource Depletion

...the future exhaustion of the coal fields is to us, — a great fact looming in the distance, full of changes for the race, but without immediate application.

The fear as old as the hills--that we are going to run out of energy. Coal production has only gone up in my lifetime, largely driven by China's desire for low-cost energy.

To be fair, coal prices have shot up significantly in the last year, but I would argue this is a good thing. Coal is really dirty and harmful to human health but we've kept using it because it is so cheap.

The Remedy

Babcock has a solution for his made up crisis. People should go out to the marginal hills of Appalachia--which can not be easily be utilized with mechanized farming techniques-- and become subsistence farmers. "The natural escape from all this is the return of the masses to their normal and healthful existence as tillers of the soil, not for the sake of speculation or considerable sale, but for the means of living."

This is a terrible a idea and no one took up his suggestion. Being self-sufficient is synonymous with being indigent. Babcock would live until 1922, there's no indication that he ever left Washington D.C. where he worked as a lawyer and author. His advice was apparently for other people.

Home Tech

While Babcock was worried that advancing industrial technology would make workers obsolete, he was enthusiastic about labor saving devices for the home. Indeed, he saw these as important advances that would allow his imagined new rural class to focus more on farming than domestic chores. Here are some new and coming technology he mentions:

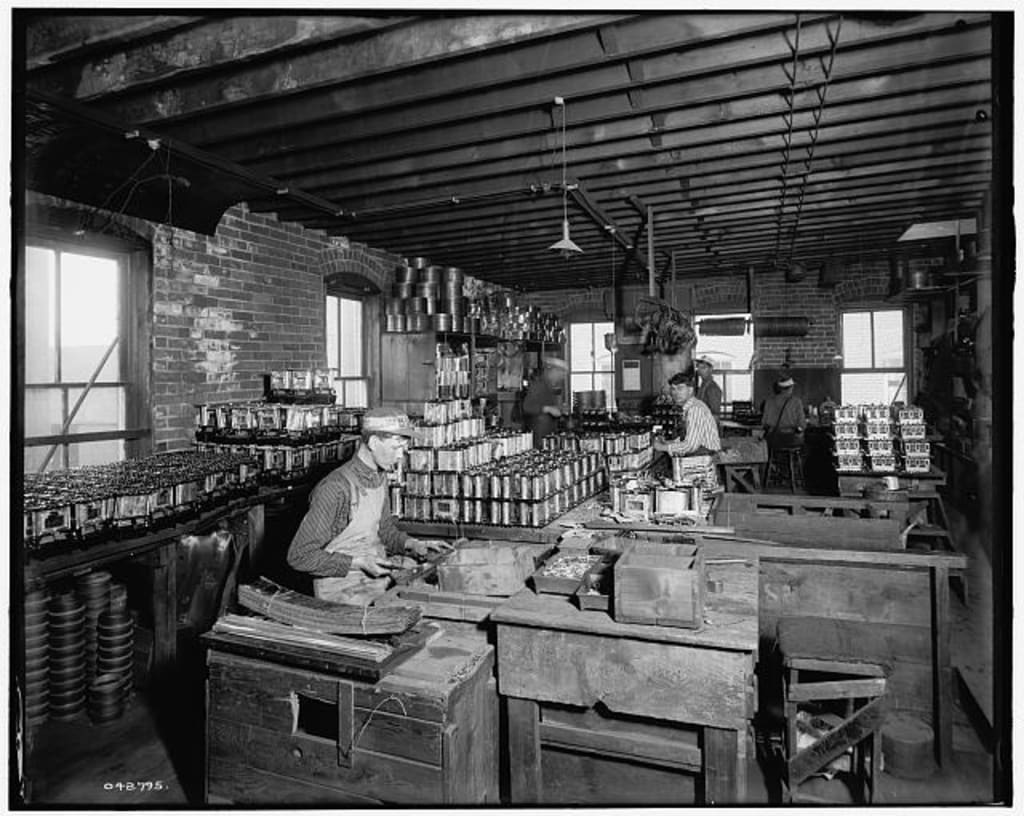

"The four or five thousand patents already issued for washing-machines attest the need that has been felt to lighten the task of cleansing clothing as now generally performed." Keep in mind that early washing machines were nothing like what we have today. They looked like this:

"Stoves have been so greatly improved as to make the labor of cooking, in a well-ordered household, comparatively light, and to insure good heating in winter." Again, nothing like stoves we have today. These would have been wood burning stoves. which have to be constantly fed, cleaned and monitored.

"...we may confidently look forward to an ice-machine of the near future which shall be as manageable and as cheap as an ordinary cooking stove. It will in time be as common to make one’s ice for the day or week as to prepare a baking of bread."

"Unfortunately, no one has as yet devised a satisfactory machine for automatically sweeping and scrubbing floors, and it is likely that these labors will be generally performed by hand to the end of the chapter." We have robot vacuums now but we still don't have anything that automatically sweeps do we?

I'm not really sure what he's imagining when he talks about a device that will set the table, but he might just be describing a Lazy Susan. "Human ingenuity has not yet invented a dining table which will automatically dress and set itself, but tables have been patented which obviate all need of passing things about by hand, or employing a waiter. They are arranged to rotate so as to bring the dishes around when slightly pulled, leaving a stationary platform or rim for holding the plates." Then the table devices get even more fanciful "There are moreover simple fanning and fly-brushing devices run by clock-work, which will keep the household free from annoyance during meals. There is not even any necessity for lifting the coffeepot and tea-pot, very neat and secure tilting frames being procurable, which reduce the effort to a minimum."

Particularly funny are his descriptions of advancements in churning, bee-hives, milking machines, and knitting. These days only dedicated hobbyists engage in these activities and to do all of them is unheard of. Babcock's distrust of industry meant that he failed to see a future where everyone would simply buy their butter, honey, milk and clothes from the store.

Babcock makes his case for inventions making it to the countryside with this example: "Riding through a dense piece of woodlands in one of the more sequestered counties of Maryland, I came on a cluster of negro cabins, and in the first one of them that I looked at was—a sewing-machine." Oofff. It kind of sounds like he just went uninvited into some black people's home to examine their stuff.

Conclusion (his, not mine)

Babcock saw his vision as not a pie in the sky aspirational but as inevitable. "It is a life which can be made a success, and which will be one day the rule rather than the exception." This development is nothing but positive since there will be "occupancy of its many places now lying waste." (i.e. all land occupied by people). Future generations will be prepared when the coal fields give out. People will live in "a more placid state than our own, in which personal desire shall play an unimportant part..." It's not really clear why subsistence farming will cause people to reach Nirvana. If anyone wants to try it out, please let me know.

All images in the article are from the Library of Congress.

About the Creator

Buck Hardcastle

Viscount of Hyrkania and private cartographer to the house of Beifong.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.