Science of Identical Twins

While two babies with identical DNA may seem miraculous, the science of identical twins explains the many similarities that go beyond looks.

“Double your pleasure, double your fun” couldn’t be more true when it comes to identical twins. Starting with the moment your obstetrician tells you, “There are two of them,” your life is never the same. Twins are double the fun and doubly amazing. Aside from the remarkable science behind them and the totally random happenstance of their creation, the very fact that two people can have identical faces and DNA is just miraculous. Here you have two babies who have spent nine months keeping each other company in the womb and then, upon being released into the world, continue to amaze all those around them. Parents of twins have reported identical sleeping positions, finding their twins sleeping in the same bed; As babies, when they would nap in the same crib, and even if they started out on opposites sides, they would always end up holding on to each other, most likely as they did in-utero.

Identical twins have been known to pull practical jokes on their parents, friends and teachers-fully taking advantage of the fact that few people can actually tell them apart. They are each other’s built in best friend and companion. Is it true that if one twin gets hurt the other feels the pain? Some say it is. Other studies show that being a twin can help you live longer. The very fact that you have a built-in social network, someone who is just like you in every way, is an element of the science behind that theory. Always having someone to talk to, whether they like it or not, and always having someone who has your back, adds to the quality of life. And when identical twins end up having their own identical twins it’s mind blowing. There are few things cooler than an astronomical odds event happening before your very eyes.

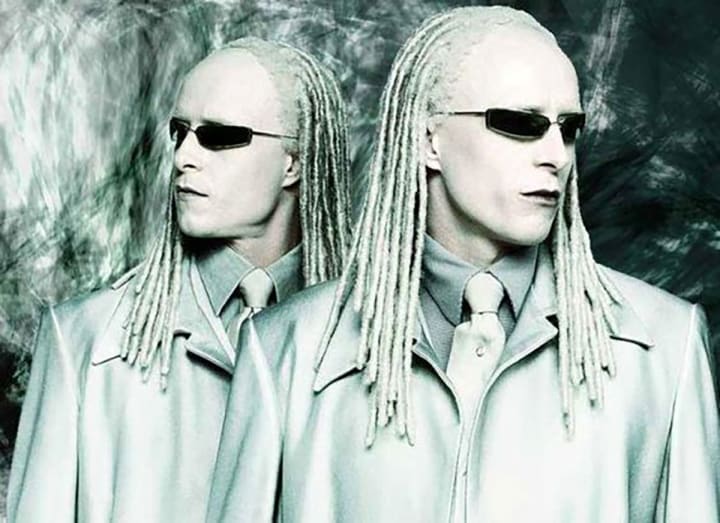

Nature's Experiment

From Lydia Fairchild in The Shining to Sarah Paulson in American Horror Story: Freak Show to Mary-Kate and Ashley Olson, twins show up often in pop culture. Perhaps our fascination with twins is that they are nature's experiment in nature vs. nurture. While they are identical genetically, some twins grow up to be incredibly similar in all aspects, while others grow up quite differently. Jim Lewis and Jim Springer, for example, were identical twins who were separated four weeks after birth and adopted by different Ohio couples. Reunited many years later, the twin brothers showed astonishing similarities. Besides their close physical resemblance and the matching first names their adoptive parents had, by chance, given them, both had worked as gas-station attendants and sheriff's deputies. Both drove Chevys and chewed their fingernails. Each had named his dog Toy, married a woman named Linda, divorced her, then married a woman named Betty. In each of their gardens stood a tree encircled by a white wooden bench. The twins' circumstances beg the question of what significance genetics have on the people we become.

Does the hereditary endowment bestowed upon us by our parents at the moment of conception make us who we are-even establishing our rate of aging and the decade in which we're likely to die? Or does what happens to us after we're born count for more? Nature or nurture? The debate has most often surfaced in connection with intelligence, where it has always roused controversy. The specter of "biological deterism" looms over other traits with genetic roots-including vulnerability to disease, the aging process, the personalities we form during childhood and carry into old age, and longevity in general. If a particular gene-borne illness runs in our family, we may yield to fatalism, but if the influence of genetics on our health is weak, we're more apt to take on active stance. For researchers, an instructive way to approach how genetics impacts longevity is to look at twins-not all of whom are as uncannily similar as the two Jims.

Niels Juel-Nielsen

One key study of identical twins separated at birth and reared apart was done by Danish psychiatrist Niels Juel-Nielsen beginning in the 1950's. He studied only a dozen pairs of twins, but he studied them in excruciating detail, interviewing them repeatedly, taking their personal and medical histories and giving them medical and psychiatric tests. He then checked on them 20 years later, when most had reached old age. He was struck by the likenesses he found among them, but also by the differences. Kamma and Ella, separated the day they were born, both grew up in rural Denmark. When Juel-Nielsen first met them, in their middle age- "it was difficult to specify how they differed." Both were calm, initially reserved, but later more talkative. Both were of average intelligence, wore glasses and had developed migraine headaches when they were about 10.

At about the age of 50, Kamma began to have heart problems. She had a heart attack when she was 59, had a second heart attack the following year, was diagnosed with breast cancer at 68, had a mastectomy and died soon after from a massive internal hemorrhage. Ella, on the other hand, had slightly elevated blood pressure and mild diabetes when Juel-Nielsen last checked on her. At age 73 she was in good health, having scarcely set foot inside a hospital in her life. Juel-Nielsen's case histories were studded with such dissimilarities. What might account for such discrepancies? Juel-Nielsen never reached a conclusion from the data he collected. Researchers have always hoped that the definitive answer would lie with twins. Because identical twins have matching genetic material, the ways they may come to differ in later years must be due to environmental influences, and any likenesses between twins separated at birth and reared apart must be due to their heredity.

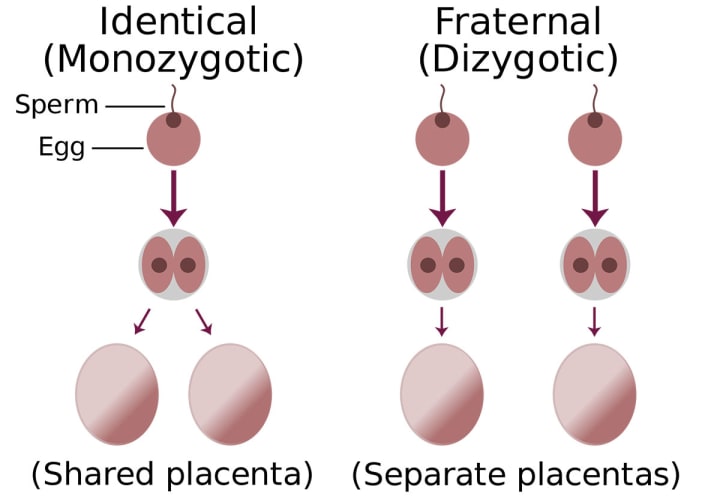

Image via Wikipedia

Science of Twins

Of course, these theories prove tricky to interpret and apply. Twins are a relatively select group. Births of identical twins amount to less than one half of one percent of all births, and the subcategory of identical twins reared apart typically comes to only about three sets per million people. Identical twins raised apart aren't always raised so differently. "Selective placement" often results in adoption by similar families, muddying the experimental waters. For all their shortcomings, however, the science of twins and twins studies are still about the only game in town, offering what scientists term "the best, if not the only, handle on the genetic aspects of aging." Today, the insights that twin studies shed on adult, vulnerability to disease, and aging are voluminous.

For example, identical twins have been shown to be twice as likely as fraternal twins to both get cancer. They are similarly more apt to share any tendency to high blood pressure, varicose veins, heart disease, arthritis, and tuberculosis. One study found that identical twins die only three years apart on average versus six-and-a-half years for same-sex fraternal twins and ten years for opposite-sex fraternals. These similarities hold true psychologically as well. For almost every behavioral trait so far investigated, from reaction time to religiosity, an important fraction of the variation among people turns out to be associated with variation.

On the other hand, even for diseases in which genetic factors are known to play a role, such as cancer, the fact that one identical twin gets the disease scarcely guarantees that the other will. While the concordance rate for cancer in identical twins is about double that among fraternals, the actual rate (9.8 percent) means that for every identical twin whose twin also gets cancer, nine other pairs don't share the same fate. These studies have also shown that our genes do not control a biological switch that limits our life span. If this trigger age existed, it would vary on the basis of hereditary factors. With identical twins, it ought to be the same. Thus, one twin's demise should be followed by the other's within a year or two at most. Studies have shown that this doesn't happen. Twins reaching an advanced age don't, as victims of the hypothesized genetic switch, drop off together. Once a twin dies, there is still plenty of statistical variation in when the second twin dies.

Studies regarding cognitive function showed similar results surrounding Alzheimer's. While having a twin with Alzheimer's seemed to increase the second twin's chances of developing the disease, there were plenty of twins who did not develop Alzheimer's. This data tells us that inheritance is important, but that factors other than genetic have an effect, especially on age at onset. Whatever the precise role heredity plays in our health, adult personalities, and longevity, it doesn't mean we should simply shrug, chalk things up to our genes, and resign ourselves to our would-be fates. Twins researchers caution that the worst lesson to draw from studies that demonstrate genetic influences is helplessness. Our genes set a pattern of development, making certain outcomes more likely than others. This doesn't mean we can't fight these patterns.

In one sense, the precise balance between nature and nurture may matter little in the end. We can't put precise percentages on the weight of environmental factors, but we do know that they play a substantial role. Because they do, room remains to intervene, to change one's life, to eat more sensibly, exercise, reduce stress, behave more rationally, live more intelligently, and live longer.

About the Creator

Stephanie Gladwell

Mother of two, educator of many. Teaches middle-school biology and chemistry. Always interested in exploring the unknown.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.