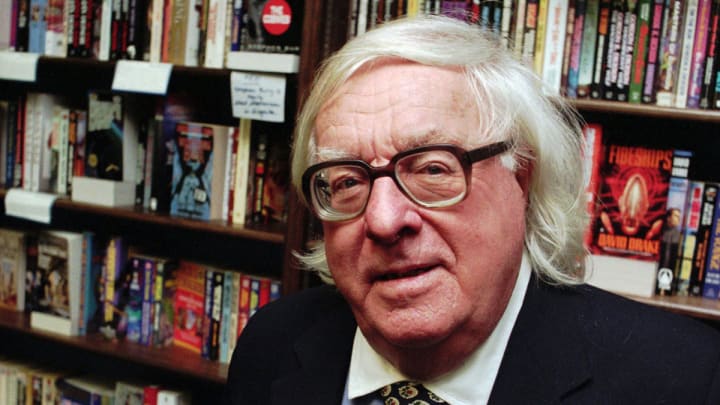

Ray Bradbury Interview

Ray Bradbury discusses sexuality, laughter, and his success as a writer in a revealing interview.

Ray Bradbury worked and wrote in a two-room office on Wilshire Boulevard in downtown Los Angeles. The rooms exploded with yellow brightness, and a visitor leaving the uproar of the street below might have felt that he had somehow walked into the middle of the sun. A gigantic, 15' high, stuffed Bullwinkle sat in the outer room, covered with hats and comic-book clippings, child's drawings and baseball cards. It set the tone for the man it served. "The problem with so many of the modern American writers," said Bradbury, "is that they exist in a world without children. I don’t believe they were ever young."

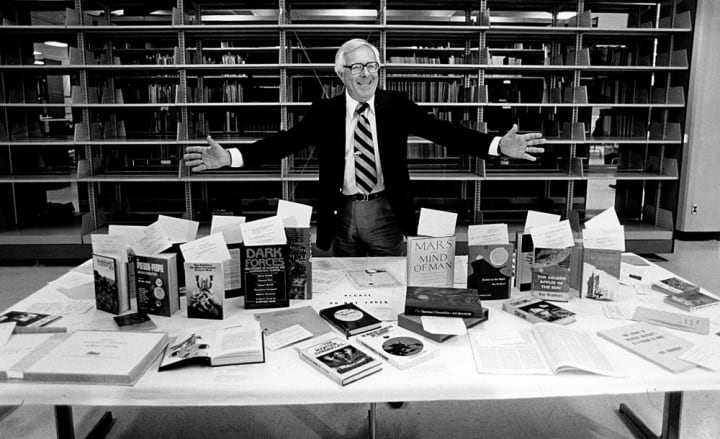

Science fiction author Ray Bradbury passed away in 2012. During his lifetime, he was married and had four daughters. While he was living, he achieved the acclaim and the popularity that most great authors earn only after their deaths and is still considered one of the greatest sci-fi authors of all time. His work still holds particular appeal for the under-thirty set. Many of the best Ray Bradbury books, The Martian Chronicles, Fahrenheit 451, and Dandelion Wine are among the most widely read works in contemporary fiction. As a short-story writer, Bradbury is an acknowledged master. His stories have appeared in every major publication, and collections of his stories, The Golden Apples of The Sun, October Country, R is for Rocket, and The Illustrated Man, among others, are read and studied in almost every school in America. Films have been made of Fahrenheit 451, The Illustrated Man, and Something Wicked This Way Comes.

For years, critics and readers tended to think of Bradbury merely as a writer of science fiction. Only later in his career did his power as a humanist-philosopher become recognized. An observer of Bradbury must recognize the irony of all this, for it is his philosophy of affirmation, of joy, that gives Ray Bradbury's work its greatest power and importance. "I give you reality, with the addition of love," says Bradbury. "I interpret reality. Too much of today's literature merely reports reality; but that isn't what we need. We need philosophers, writers who say: 'Look, we're alive... we've got problems... now here’s what we do about them.' "

Bradbury became visibly angry whenever he spoke of the existentialists and writers of despair. He blamed an obsession with despair for much of the trauma that we put ourselves through as a nation and as individuals. "Those writers who merely dwell on despair without offering solutions," he said, "are preying mantises without jaws. I’m busy making babies and they're telling me everyone is dead."

But Bradbury was not always beyond despair. He admitted that he fell prey to the agony of the Second World War, and the nuclear weapons that the war engendered. He conceded that many of his earlier stories, "There Will Come Soft Rains," for example, were born out of the horror of the atom bomb. He knows, too, that love cannot last, that men grow old, that men die. But men also laugh, and roar through sex, and are blessed with the gifts of friendship and children and good work to be done. Life is all things. "Half of me is sunlight, half of me is shadow, and it has to be both," said Bradbury. "All I want is to be part of the fecund process by which the universe is trying to discover itself, and to have fun doing it."

In this vintage Ray Bradbury interview, originally published in Genesis magazine, the master of sci-fo discusses his writing, his life, and the current and future state of the human race.

Genesis: How do you feel after you've finished a book?

Bradbury: Every time a book is published, there's two things that happen—the day a book goes into the mail I am one up on death, you know? I say, "Okay, death, there you go. One more right in the chops!" and then after the book is published I carry it around with me for about a week. It's my baby. I can hardly believe it's there and I keep staring at it and this seems terribly egotistical but I think it's only natural because you love it so. People say, "What's new?" and you say, "Well, here it is! Now that you ask, here it is in my hand." Those are happy times.

Why is there very little sexuality in your work?

I think it's because I have no hang-ups. People often say to me, "How come you don't fly? You don't drive? Isn't that ridiculous for a science-fiction writer? How do you explain this paradox? You're writing about these things and you don't do them." And I say, "Of course, that's exactly it." A writer writes about those things that he can't do. His hang-ups. Now I was afraid of the dark until I was twenty-one, twenty-two years old. Perhaps some of that is still in me. So my first books are excursions in darkness, trying to make do with my fears. And out of these weaknesses I made strengths. So it is with sexuality. If sex doesn't appear in my novels, I must be giving forth these energies, exploding my sexual energies in correct proportions. Loving people in just the right way. So I don't have to write about them.

How can you write about love without describing sex?

I don't want to do the easy thing. A lot of people are doing that now and cashing in on it, and I'm a little afraid of being flip and doing the "in" thing. I want to do the honest thing. I may find a way of describing, at a certain time in my life, certain problems, especially the problem of aging. Then I will probably do a conventional novel or a short novel on this subject. The challenge will be in doing it freshly. There's no reason in doing it unless you can state to the reader: "I am now going to do a cliche. I'm going to give you the names of all the characters, all the relationships, all their sexualities ahead of time and then I'm going to do a mirror trick for you and bring it off and you're going to stay with me even though it's a gigantic cliche." That would be the challenge, to explain everything there is about love and life and sexuality in a novel, with say, three or four people. Other people try to do this and bore us silly. I want to do it and make you fall back in love with love and sexuality in its right proportions.

Why is so much that's written about sex so boring?

Because that is not what life's about. The real problems come after the act or before the act. Anybody else's sex is automatically boring. We're really not that intrigued. What's interesting is the making do before and after. We behave very well towards one another in the middle of our sexuality. What we're looking for is good conversations in this life of ours. We should pick partners, or wives, or husbands, who are fun and who are idea people. That is, if we have any brains at all. We shouldn't just want a pretty person, because we all know what bores they are. They're just so busy looking in the mirrors. They're lousy company. We want company and we want conversation. So that’s the challenge of the sexual novel. And that's the challenge of all friendships.

Ray Bradbury by L.J. Dopp

What do you think makes a woman sexy?

Well, I think intelligence, along with all her other attributes. If you meet a really bright woman, who isn't out to hurt you but who is a challenge as a conversationalist, this automatically makes her more intriguing. She can hold up both ends of life at the same time. She is a creature of flesh and she is a creature of the mind. This has always been attractive to me. As a result, I've met very few women in my life who are totally intriguing. Katie Hepburn comes to mind immediately. Somebody said, a few years ago, "When L. B. Mayer stepped down from MGM, Katie Hepburn should have taken over." I agree. She is the perfect woman, a combination of wonderful attractions.

Could you write a sexual novel freely or would you be afraid the kids would expect another impish Bradbury and might be confused by it?

Well, I believe in the power of the imagination. I would probably leave things out, as most of the good novelists have in the past. You can imply sexuality. A good example is in Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier. It's not a sexual novel but there is the presence of a very strange, and as it turns out, evil woman. It's all done by implication. We realize that this woman did a lot of sexual things she shouldn't have. But there's no need to go into them. We can guess at what they were. Just like swearing, which is a real bore. It's much better to say, "he swore," and then the reader fills in his favorite swear word. I believe strongly in the power of the imagination.

What about group sex, exhibitionist sex?

When a cat goes out in the garden to make its toilet, that's a very private thing and it doesn't want people around. This is genetic. Also, most sexual activity among most species of the world is a private thing. If we see this is true with animals, why shouldn't it be true for us? Why should we separate ourselves out simply because we can think about it? That doesn't make us any more knowledgeable than the animal which has enough sense to do the thing in private. We have to find what the genetic base for any custom is. If we've given up the custom we better make sure we haven't given up the genetic impulse, too, because we're going to have to go back to it eventually. We have rituals for death, birth, and all kinds of things in life and we're finding we have to rediscover these things. We've thrown them out for a few years but we can't live without them.

How do you feel about bisexuality?

I think it's probably going to happen more between now and the end of the century. I think a heck of a lot more people are more bisexual than they ever guess, or remember. Our greatest friendships occur—I can only speak for men—between ten and twenty when we have little sex with the opposite sex and when all we have is friendship. The fantastic love that occurs within the framework of those friendships is partially sexual. It may never come to the surface or manifest itself sexually but there certainly is repressed sexuality.

via scriptphd.com

Why are we so afraid to admit this? Are we afraid of the word bisexual?

No, I think the word homosexual is what we're afraid of. I think bisexual will come into play and be an easier word to get on with. Because it implies shadings and multiplicities and varieties of feeling which we all have. Male love is a vast reality in the world. Always has been. I'm not speaking of homosexuality. I'm just speaking of the ability to love one another. I find if I'm not careful in discussing this subject, many students think I am anti-homosexual. They say, "They're people and they're nice and they're human just like everybody else." I have to immediately say "I’m glad you're defending them and I do, too. You shouldn't think that I have any of these antipathies which have grown up in parts of our society."

There are times in all of our lives when we do not have female company. In the ideal love relationship between a woman and a man there is that wonderful time after sex when we philosophize about the universe and our functioning within it. This "talking period" makes for a good love relationship. But we can't always have that within sexual relationship, so the society that would really function well for me would be one that encourages boys and girls to touch their friends. I'm not saying have sex with them. I'm saying that the warmth of the human body is so important that boys should be encouraged to cuddle one another and touch one another, to hug and even to kiss. That doesn't mean the sexual kiss, it means the kiss of friendship, the hug of friendship. Someone is lying there with you while you talk out your problems so that you don't go mad during your teens. Now we all need a friend like this. We should be allowed to touch a little more and to risk the sexual thing. I guess what we're afraid of is if we encourage boys and girls to do this, they'll take the next step over and never come back. But I don't happen to believe this will happen.

Have you ever had a sexual relationship with a man?

No, I can't really say that I have. But I've come very close to it. Of course, my relationships with all of my friends are hugging relationships and semi-kissing relationships. They've had to put up with this from me and I've warned them all, "Look, if you're going to be my friend, you're going to have my fingerprints all over you. And you gotta accept it." If I like people, I cannot help but touch them as long as they understand that it's the touch of friendship.

What do you think of the whole Esalen thing—the group encounters?

I think there's a lot to be investigated when people are ready. I'd like to see us touch each other more and love each other more and tell our loves more, when we're ready for it. It depends on the individual. I would like to see a more affectionate race of people, male and female.

When do you see that happening?

Oh, I think by the end of the century. We seem to be learning; I think there are many things we can learn. I like the Mediterranean people. I like the Russian men that I've met who rush over and crack your ribs and hug you and kiss you and give you vodka and drink you under the table. Well, that's irresistible. I'm that way myself and my friends have had to put up with it.

You have portrayed the experience of growing up as one of great joy and wonder. Tell us about your childhood.

Well, of course, you know, when you consider growing up in northern Illinois in the late 20s and early 30s, it wasn't much different than it is today in almost any section of the country. If you look at an average child and talk to him and consider his family’s income level, you'll discover, in most cases, that the child doesn’t even know that he or she is poor. No matter what the traumas are, even in the middle of the worst wars, children survive. They survive quite often much better than adults do—because whatever the reality is, they take it in and chew it up and make do with it. They're able to fantasize, something that many adults lose later, much to their bereavement. It's a great shame when we lose the ability to take a thing and say, "I see this reality, but I will interpret it thus and so."

For example, I grew up in Waukegan, Illinois. It never crossed my mind that the lakefront was ugly. Half of it was a shore where we went bathing and the other half was old docks and harbor facilities. You go back and look at those things today and they're ugly. But, when you're a child, a heap of coal is beautiful. It looks like a ton of black insects. And you look at it and you catch the blue meteorite glints of that coal. I used to love to go into the cellar when I was six or seven years old, and watch the ugly coal pouring into the cellar down the shoot when the truck brought it to our house. For me, it was a beautiful piling up of meteorites coming out of outer space, hitting that shoot and coming into my very own basement, where I then could imagine, late at night, that out of those stacks, mysterious creatures would come and wait for me in the basement.

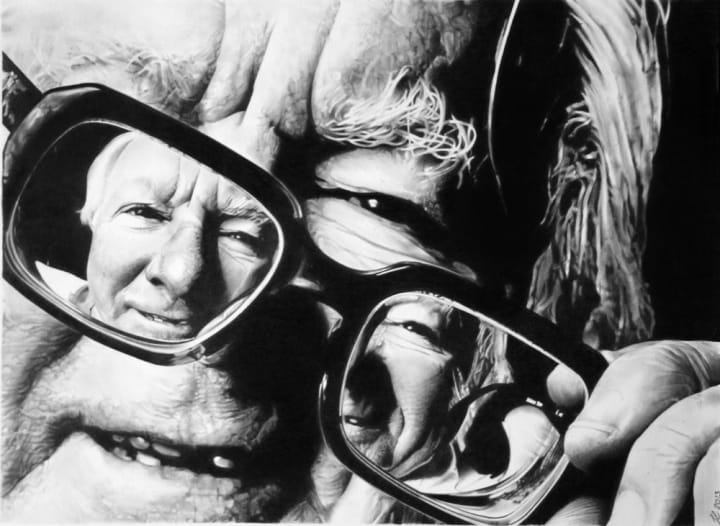

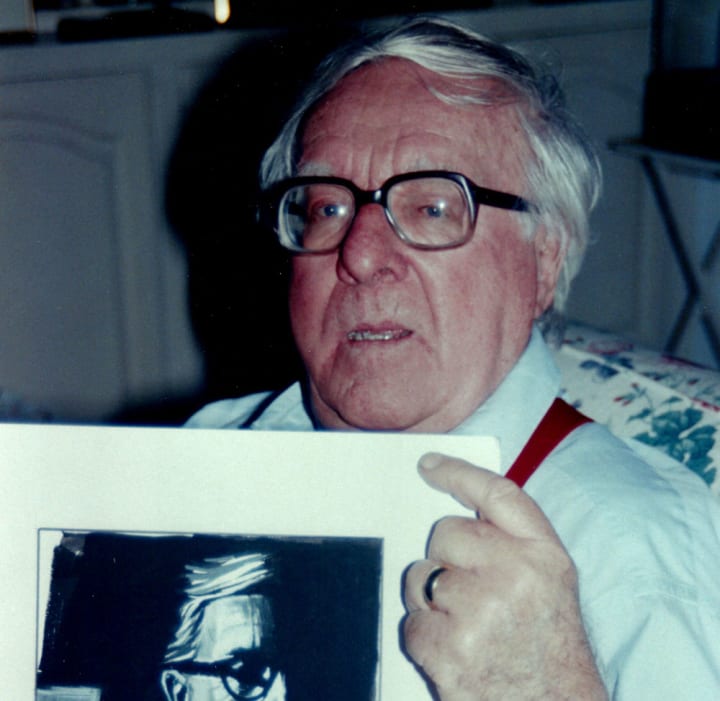

Ray Bradbury by francoclun

If it takes a child's innocence to see that you can live life joyfully, how is it possible for an adult to recapture this?

I think, if you're fortunate, you can lose your innocence in one way but still retain a childlike vision. I don't know how to advise people about this except to be in love on as many levels as possible. Even that is hard because if people don't have the capacity to love, it's very hard to teach them.

How do you explain your particular appeal to younger readers of high school and college age?

If I had lived in Baghdad a couple of hundred years ago, on the Street of the Teller of Tales, children would have come there and sat around and I would have told them stories. The reason why the Old Testament and the New Testament are still around is because of the gift of metaphor. So I think I have picked up—from the Bible and from various poets, and from the comic strips and from motion pictures—the ability to tell things tersely, to the point, and to juxtapose such diverse elements that people can't resist. In other words, I come up with an idea like a dinosaur hearing a fog horn and swimming in out of the ocean deeps one night thinking it's another dinosaur and finding it's only a lighthouse with a foghorn. So he knocks the lighthouse down and goes back out into the deeps to despair. It's a perfect metaphor and it's the way I seem to work all the time. I can't resist compacting things.

The great works or even the minor works in the children's libraries are those which have memorable metaphors. We think of Robin Hood, Jekyll and Hyde, the stories of Edgar Allen Poe, L. Frank Baum and the Oz stories—these are things that stay in our minds. Grimm's fairy tales, Anderson's fairy tales. These and the Greek myths stay with us for a lifetime. The thing that's wrong with most literature today is that we haven't borrowed enough from our childhood. What is wrong with the modern American novelist is that he's turned his back on his own roots—what really excited him, what really was fun about reading. I spend as much time in the children's section of a library or a bookstore as I do in the grownups' section. I know that the average American writer doesn't do that. As a result, he's withering. His roots are withering. He can't put out any flowers. There's simply no way. You gotta keep in touch with both halves of life. As one of my characters in a story said to another character, "Sir, have you proof of childhood?" Most novelists today do not have proof of childhood. These people, the modern American novelists, exist in a world without children. I don’t believe they were ever young. And that's because they haven't gone back, and they haven't kept up.

I spoke to a seventeen-year old boy and asked him why he liked your work and he said, "Because he's a kid." Do you see evidence of that as you talk to the kids?

Yes. It's very gratifying. speak to their needs, to their hunger, to their need to cry in certain ways at certain times. I speak to their need to know their own evil at times. One of my most popular stories is called "All Summer in a Day," which is a very sad and terrible story about a bunch of children who lock this little girl away in a closet on the planet Venus on the one day of the year when the sun comes out. The rest of the days it rains. And they lock her away so she misses the sun. And when the sun goes away they let her out of the closet. That's the end of the story. Well, kids read that and know exactly what I'm talking about. I'm talking about them and their own evil, their own genetic evil, which we have to learn to control as we grow up.

Where are you most vulnerable?

With my friends and my children. With my wife. And when I was younger, with my love affairs. You have to be vulnerable there.

You are vulnerable to your children?

Oh, very much so. And it's very hurtful. I have four daughters and you have to learn how to go through their experiences. They're not necessarily destroyed by them but if they're not careful they can destroy you. Because you get sometimes much more deeply involved in them than your children seem to be.

via NPR

How about the current state of our nation? How would you describe us?

Blasphemous. That's good, essentially, but gives us problems. When we exploded here on this continent a couple of hundred years ago we said, "I don't like the way things are put together. I'm going to change things. I'm going to survive. I'm going to (in the words of Faulkner) prevail." So in medicine and in every other area of science and in our cities, we have attacked nature. This has gotten us into quite a bit of trouble in the last few years. We've attacked nature much too violently in some areas. We have the tough moral problem of deciding whether or not we want to use, say, DDT or stop using it and let two million people die each year as a result of malaria. That's a very interesting decision, isn't it? And when you see a baby dying in front of you, you make the decision in favor of DDT. You have to. You take your chances on the balances. So in our technologies we are revolutionary, and in the midst of our revolutions we are blasphemous because we've gone against all of the constants, or what we thought were constants in religious terms. We've said, "We will live to be not just three score and 10, but five score and 10, why not? Let's try it."

How do you talk to someone like Beckett who says it's not even worth trying?

Well, I wish he'd slit his wrists and quit. He's a terrible bore. He's a very special case. He is a praying mantis without jaws, and he's wandering around the library somewhere in the shadows and he's been dead for years. He has nothing to offer the living. He's in a catacomb. He's the guy that comes with bad breath in the middle of your love affair and leans over your shoulder. To hell with him. I'm busy making babies and he's telling me everyone is dead. But I've got the proof and he doesn't.

What was the happiest time in your life?

When I was a high school senior I knew it would be years before I would be happy in quite the same way again as I was that last year in high school when everything was going my way. I had written a student talent review. I was accepted in the student body. I was loved by a few people and admired by a few people. So I went up on the top of the school, at sunset, before the last performance of a play I was in, and wept because knew it would be years before I would be loved again. But I could see it coming and I was ready for it and I got in and worked.

What inspired you to write Something Wicked This Way Comes?

I had had ideas about the novel some years before it was finally finished in 1962. But it had been in gestation in various forms for about 10 years. And then, my father died in 1957. I think he wrote the novel for me. Two or three years after it had been published I reread it, one night, and wept because I discovered my father at the center of it, as the hero, as the protector of the family, as the man who takes responsibility and who says, "Do your worst—I'll protect my son. He's more important than my own life." My father's love wrote the novel. That was an important thing for me to discover in the book.

You have written of Shakespeare's Richard The Third and his sense of delicious evil. Is there something of Richard in you?

Of course. There is in each of us, if we're very honest. I've never had to exercise that part of me that is. The genetic shark that devours, mouths, digests, excretes, and doesn't know what it does. It's a carnivore. Boy, it just chomps and there you are. So the shark in me has never had to come to the surface. I've been very lucky. I've never had to destroy people in order to survive. But, if my life turned in the wrong direction, and everybody rejected me and I felt unloved, then the shark might come to the surface. It's there. I see little touches of it on occasion, if people cross me or if I get bad reviews on a play or a book, I have these furies within me which rise to the surface and say, "Boy, was that dumb. Wouldn't you love to knock their teeth out?" That murderer is in me.

We've talked about your success as a writer. Where have you failed?

I don't think I have anywhere, that I know of. As soon as you stop anything, that is the moment of failure. There's a point I'd like to make here that I think a lot of people don't realize. All my novels, all my short stories, all my plays are written free. No one pays me to do any of this. When they're all finished, I then send them out in the world. And maybe I get paid for them. Maybe. But no guarantees. I'm putting my head on the chopping block every day of my life. If there's anything I have to offer, it's the challenge to the young person of saying, "For God's sake, don't expect to be paid for anything. Do it! And then send it out in the world to be rejected or accepted." I'm still working free on everything I do. I occasionally take jobs in television where I'm paid ahead of time, but that's very rare.

via nj.com

Why are there so many suicides among authors?

Well, is that really true? Name the names.

Let's take Hemingway.

Well, what happened to Hemingway is his reality, if you want to talk about reality. He was in two plane crashes. You can't escape those plane crashes, they really happened. The first plane crash he walked away from. The next day, after that plane crash in Africa, he had a second plane crash which destroyed his body. He had broken bones. I think he had a ruptured spleen. It was disastrous. You cannot live in a fractured body and not have it affect your mind. That has nothing to do with creativity, nothing to do with the artist. You cannot create out of a pain-racked and destroyed body. He finally killed himself because he couldn't take the pain anymore when it was interfering with his creativity. It's no way to live. I would do the same thing. That has nothing to do with his image from the past.

Why do so many writers drink?

I haven't any idea. I think a lot of people drink a lot.

That, too, gives credence to the stereotype?

Yeah. But why do so many advertising executives drink so much? Why do so many agents drink so much? Why do so many housewives drink so much? Why do people from all walks of life drink so much? Alcoholism is a huge problem in most of the northern countries of Europe; It's a huge problem in Russia right now. It has nothing to do with intellect. What we notice is the waste. We have to make an elitist judgment here—one which isn't bad, because some of us offer more things than others. Some of us are concrete mixers. Great. This is needed and it's wonderful and fine. Some of us offer solace to the spirit on another level, either as theologians or as writers or artists. The people who can do that are rarer. We can always get another concrete mixer, but we can't get another DaVinci. We can't get another Schweitzer. They're very rare. So, when we talk about Hemingway and Faulkner and Fitzgerald, all of whom drank too much, we are talking about the waste. Other people doing it in other fields, we don't notice. They are replaceable. But a Faulkner, a Fitzgerald, a Hemingway is not replaceable. It's a great shame when they destroy themselves. For whatever reasons.

If you could live your life as any character in fiction, who would it be?

The first thing that pops into my head, I suppose, is Robin Hood! And I suppose I am in love with this story because when I was two or three I saw Robin Hood with Douglas Fairbanks—my middle name, incidentally, is Douglas; I was named for Douglas Fairbanks. I was born in 1920 and he was at the height of his fame. I had a huge love of this bouncing, adventurous, imaginative man—his zest and gusto. Every time he touched the ground he was like the old Greek heroes who took energy from hitting the earth and bouncing up again. There was a lot of that in my young character—the mysterious one who did good things and vanished in the night. I loved to hide up in trees and jump around. And I guess the next person after that would be Tarzan. Burroughs was a huge influence on me. Those romantic heroes stay with you. I can't think of any later intellectual heroes that would predominate.

Are there any people you dislike and why do you dislike them?

Well, people who confess too much and who pity themselves too much embarrass me. You must be very careful what you tell me about yourself or what I tell you about myself unless we really trade information as very close friends. Then it's different. But not if I get in a cab and the cab driver spills his guts to me for half an hour, and doesn't have enough sense to know that I can't possibly care about all this. But once in a while you hear a thing that's so shattering and so beautiful and so touching that you don't mind it and you never forget it. I got into a cab eight or nine years ago with my own children, and we were going to the beach. The cab driver, looking at my kids, was reminded of his own son. This cab driver was about sixty and he had a son who was thirty and his son, in turn, had had a son who was three who had died several months before. And he said, "You know, it's so horrible. I have to go out to the graveyard every once in a while to get my son and bring him home, because he goes out there at night and stands by the grave and says to his dead son, 'What are you doing here? What are you doing here?' " Well, that's so sad I can't even tell it without its hurting me. And that is a universal story. "What are you doing here? Why don't you come home?" Wow! That's a dagger right in the heart. And I'm sitting there with my own kids...

What makes you laugh?

I laugh a lot at myself because I find myself in the same ridiculous situations in which everyone else has found himself throughout history. Mostly we laugh at ourselves in sexual situations where we're all fools. If there's one area in which we're absolutely all the same and we share a common humanity, it's in our sexuality and the stupid things we get into as a result of the kind of errors we make there. Those are very funny. And of course the funniest moment in all our lives probably is that moment when we're in bed having a sexual experience and suddenly we sort of look at each other and say, "Hey, wow! Look at us, two naked people in bed. Isn't this funny?" We suddenly see ourselves from the outside for a moment. And you can't be that serious about loving. Loving should be like everything else. It should be a fountain, it should be explosive, it should be truly joyous, and it should be laughing at least half the time when it isn't just exerting itself.

You made laughter a weapon in some of your writing.

In Something Wicked This Way Comes, the father destroys the evil carnival with his laughter, which derides evil. He says, "Do your worst. You cannot destroy me. Even if you destroy me you can't win because I can out laugh you." What the father finally says is, "I accept the inevitable; I accept old age, I accept illness and accept death." Those are the three hardest things for all of us to accept.

How do you feel about freezing people for a future life?

Well, I don't want to wake up in a future where all my friends are dead, where all my children are dead, where everything is dead that I knew. You could write a very fascinating story, and it has been done dozens of times now by better people than myself, of a man waking up in that future and going mad immediately. You cannot exist in a vacuum. A man who is frozen and wakes up in the future, is automatically in a vacuum. He has nothing to refer to. Everything is gone. The immense melancholy that would hit him when he suddenly realized that all his sons and daughters were dead, all his aunts and uncles, his mother and father, his wife, all of his friends.

Would you want to be reincarnated?

Sure—to start over fresh with the mind completely erased and with maybe just a little knowledge that you were here once before. That would be nice. That would be at the center of your consciousness—a little kernel for you to touch your tongue to on occasion and say, "Oh, isn't it nice to have the gift again. I'm so glad to be reborn."

What will happen when the day comes when you sit down and you find you can't write?

I don't think that will happen because I always have enough sense to do something else. If something doesn't work on a particular morning I do something else. I write a poem or I write a play or I do a short story, or I work on a novel. I have files put away from 35 years of writing and it's like a huge brood of little chicks. There are thousands of these little chicks in there and I open the bin and peer in there and say, "Who wants to be born today?" And there's this big gabble of voices, and whoever yells the loudest gets taken out and written. So I have these thousands and thousands of little poems and ideas, and I just go through the titles and look at one and I say, "Well, that's interesting. I remember I put that title in 20 years ago." And I take it out, and I look at it and say "Yes, it's ready to be born." And I sit at the typewriter and an hour later the story's finished.

Explore Ray Bradbury's Work

Now that you have read about the man's life and world views, explore the imaginary worlds of Ray Bradbury in his work. Bradbury wrote countless books and stories throughout his life, so here are our recommendations.

The October Country contains the haunting, harrowing, and downright horrifying tales of "The Small Assassin," "The Emissary," "The Wonderful Death of Dudley Stone," and many more of Bradbury's renowned short stories.

Something Wicked This Way Comes is a dark fantasy that remains distinctly earthly, and is one of Bradbury's few works that don't cross the line into science fiction. The book is set in the American midwest of the 1930s, weaving together elements of mystery and sinister foreignness with the nostalgic setting to create a single dark narrative.

Bradbury Stories features 100 of Bradbury's greatest short stories. The selections were made by Bradbury himself, and span his entire career. Many works contained in this volume have not been republished for decades.

About the Creator

Futurism Staff

A team of space cadets making the most out of their time trapped on Earth. Help.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.