If Creative Thinkers Are So Clever, Why Do We Still Have Problems In the World?

The Problem of Restless Minds

Restless minds

You would have thought, wouldn’t you, that by now we would have sorted out how we want to live, what political and economic system works and we would have found an excellent comfort level, where nothing changes, and everyone is happy… Brave New World?

Sounds more like hell. Nothing changes, no thrills, no spills, no passions, no mistakes, no loves gained and lost, no joy (happiness without joy, is that possible?).

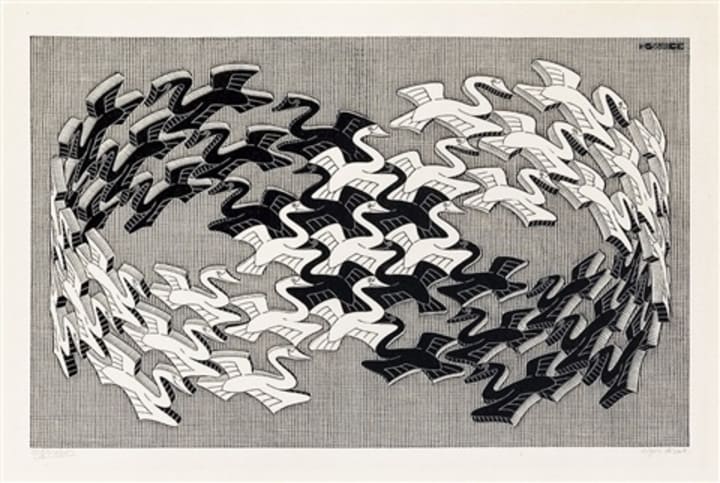

Perhaps that explains why it is that, no matter what our situation, we fiddle and tinker with it to try to wrestle it into a shape that fits us. That makes sense our restless, creative minds. Its an endless bounce between stability and chaos, automation and novelty, risk and reward, and pleasure and pain.

Between the desire for homeostasis and the desire for change, lies the natural habitat of creative minds. The result of this dichotomy is the relentless creative mind. Creation and innovation are what humans do. Creativity is the natural state of the human mind.

Rapid Change becomes the norm.

If there’s one phrase that condenses our current situation, it would be Rapid Change. It feels as though the rate at which we are changing and innovating is gaining momentum exponentially. As we plunge into the information age, our relationships, our communities and our societies (and perhaps identities) are all questioned and re-evaluated.

The results of rapid change quickly become the norm, and indeed change itself becomes the norm. The first desktop computer, the Programma 101, was unveiled in 1964. The first mass-produced mobile phone was launched by Motorola in 1973, The first SMS message was sent in 1992, the iPhone only appeared in 2007. According to GSMA intelligence data, 5.24 billion people (and counting) now own a mobile phone. All this has happened in the last 60 years. We have taken the change onboard and have adjusted our lives accordingly.

Repetition Suppression.

The more familiar something is, the more we adapt and accept it. This is a phenomenon called “repetition suppression”. Our brains get used to something and, as a result, gets less and less responsive every time it is exposed to it. It becomes the norm. There’s a good reason for this, this is how our brains make habits so that we don’t have to re-think it every time and therefore consume lots of energy and lose lots of time. We need quick, automatic reactions for our survival. It wouldn’t do for us to be considering all the possibilities and data when we are confronted with a hungry tiger. The best thing is to react automatically and run very fast (or perhaps attack it).

Novelty is essential for our brains, but to be novel, it must be new and stimulate us in some way.

Prediction.

Because our brains are also pattern-seekers; when events repeat, we create a pattern which allows us to predict. By predicting well, we save energy, and we make our internal stories that tell us how the world works. Now that’s all well for energy conservation, but it conflicts with our equal need for novelty, surprise and stimulation.

Familiarity breeds indifference

As repetition suppression gradually takes over, our focus and attention begin to wane. Yet we are hungry for the new and the unfamiliar. We get caught between familiarity and novelty. Between habit, assumption and belief on the one hand and stimulation, newness and unpredictability on the other, our brains run from pillar to post trying to satisfy both ends of the spectrum. It’s no wonder that we are often conflicted in what it is we want. Familiarity breeds indifference.

Yet, this is the learning cycle. We stimulate ourselves with the unfamiliar, which, often by repetition or association, we commit to our memories where they become part of our store of knowledge, ready to be accessed at any time (hopefully). The critical thing to remember here is that this is how we learn new things and every new thing, no matter how small, affects how we view the world. These new items “flavour” our habits, assumptions and beliefs and steer them towards a mental model of how the world works. Implicit within that is that we form those mental models to be able to predict how the world works.

We crave the new (and funny).

Within reason, we mental set our personal balance between novelty and familiarity. We crave new stimulation. We don’t want perfect predictability or instead we don’t wish for perfect homeostasis. We need a level of surprise, and the function of our brains have evolved to reward us for that stimulation. Surprise and novelty satisfy our biological desires that trigger reactions in our brains.

Humour and jokes are something that demonstrates how this happens and the pleasure we have in moving from predictability to novelty.

Most jokes and things we find humourous will lead you down a predictable pathway where there is an expected response or outcome and then, at the last moment, will change direction and deliver an unexpected (not predictable) answer, which makes us smile or laugh, particularly if the change of direction is relevant, as in this advert from the Ely Standard.

“Our paper carried the notice last week that Mr Shaw is a defective in the police force. This was a typographical error. My Shaw is really a detective in the police farce”.

The predictable pattern is broken, and that fulfils our pleasure in the unexpected and novel answer. Surprise gratifies us.

We try to avoid repetition and seek out novelty whilst at the same time desiring predictability and pattern. We use our beliefs, knowledge and assumptions to assemble predictable patterns.

However, when we step aside from our mental models and make new associations, we step away from our assumptions into uncertainty (non-predictability) and risk.

Constant creativity keeps us engaged

Creativity, genuine creativity, resides in this area just outside of our bubble of assumptions, beliefs and habits. This is what Stephen Johnson calls the adjacent possible. We use some of the old knowledge we have and balance it with a new observation or association, thereby creating a new idea. Creativity, by its very nature, lives in this area of tension, risk and uncertainty. We transition from what we know (or believe we know) to what is new and unstable.

New ideas, if adopted, then form new or adjusted assumptions and cycle through to become habits and, eventually, beliefs. It is the tension between novelty and predictability that starts the creative process. Novelty in and of itself is not necessarily a valuable creative idea.

Creativity is the result of our evolution.

The more we use a new idea, the stronger it becomes. In terms of the neural pathways in your brain, the more you use them, the stronger they become. Repeating patterns of predictability and behaviour.

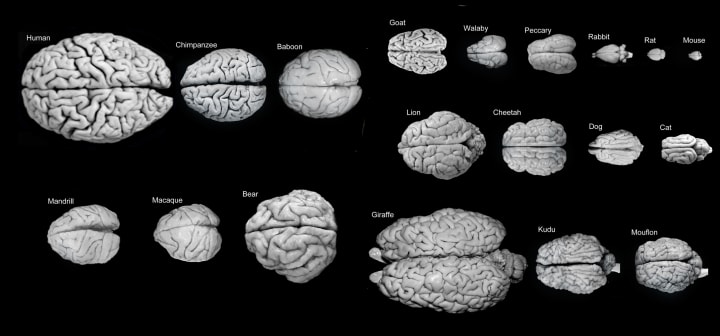

Creativity is the result of our evolution and is one of the defining differences between us and the majority of the rest f the animal kingdom. That’s not to say that other creatures don’t have creativity in their arsenal, but Homo Sapiens seem to have this in abundance.

Our ability to solve problems and apply creative solutions has to lead to the explosion of complex interactions and cooperation and, in turn, has probably lead to the expansion of our mental capabilities.

“The massive expansion of the human cortex unhooked huge swathes of neurons from early chemical signals – hence these areas could form more flexible connections. Having so many “uncommitted” neurons gives humans a mental agility other species don’t have. It makes us capable of mediated behaviours”. David Eagleman.

Automated behaviour isn’t capable of innovation.

What-if…

The equipment we have, our brains, are the ultimate virtual simulators. Combined with our ability to predict, we simulate possible future scenarios in our minds. Again, this saves energy and error. It could be costly to make an error of judgement about the behaviour of a mammoth, so we run simulations in our minds, and we do this all the time. In this way, we test out our predictions.

Children are particularly good at simulating with play. Creating scenarios allows children (not just children) to test possibilities and roles to learn how one thing fits with another.

This is the work of the imagination and visualisation. What-if tests the robustness of an idea and the risk involved in the reality of the situation. This too is a potent creative skill and applies to everyone in every case. We hypothesise about our behaviour and the behaviour of others, and the results allow us to adjust our attitude and change our effort.

The ability to speculate mentally is as essential to envisage alternative realities allow us to peer into worlds that may not have formerly existed. Copernicus visualised a heliocentric solar system. Einstein saw deep into time and space. Darwin saw the origin of species and how evolution had created the world we live in. George Lucas created the Star Wars universe. Adam Smith rationalised modern capitalism. Gandhi saw an independent India…

Creative minds.

Creative minds create ideas and ideas, how we think, shape how we behave, which shapes our societies and cultures. The driving force for change is the restless creative mind. Creative thinking becomes a social act because we are all part of our cultures, which are shaped by our ideas. Restless minds imagine what might be and then share their concepts with others until these become the norm. To implement further change requires stepping into uncertainty and risk.

Complexity naturally occurs when many people (minds) interact without a common agreement. So that the power and strength of mutually shared values and ideas, must, by necessity, underpin our cultures into creating a norm.

Creative thinking exists at the edge of the norm, which is why new or conflicting ideas are challenging to accept because they break with the accepted predictable pattern.

Innovation is the natural state for humans, we’ve used it to change and adapt throughout our evolution, and as a result, we have our place in the world. Unfortunately, change is not always a change for our own of the planets’ good. We can’t help ourselves and thank goodness for that. Creativity is driven by a biological necessity and is a quintessentially human quality.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.