Gore Vidal Interview

Gore Vidal discusses presidential affairs, his writing, and sexual roles and pleasures.

When Gore Vidal published his first book, Williwaw, he was just twenty years old and stationed at an army base in Idaho. The book received critical praise as an excellent first effort by a young writer. Three years later, in 1948, Vidal published his second novel, The City and the Pillar, and the terrible swift sword of the literary establishment came crashing down upon him. The book's hero is a red-blooded American boy who, it happens, enjoys sleeping with men as well as women. Critics in that post-war neo-Victorian era were not about to stand idly by and watch American morals be "corrupted" by "perverts." Many critics decided that they would never review another of his books, and Vidal found himself banished from the literary mainstream at the very start of his career.

Looking back, it seems peculiar by today's standards that such a relatively mild work as The City and the Pillar should have been so controversial. Vidal, at the time, was unaware that he would be risking the wrath of what he calls the "American heterosexual dictatorship," although he knew that the book would negate his childhood dream of becoming president—which, he told Penthouse interviewer Ken Kelley in this 1975 interview, was his ultimate sexual fantasy, as well.

Vidal's family belonged to the American aristocracy. His grandfather, Thomas Gore, was the first elected US senator from Oklahoma; His father, Eugene Vidal, was a West Point football star and a member of Franklin Roosevelt's inner circle of advisers, and his stepfather was Hugh Auchincloss (who was also stepfather of the Bouvier sisters—Lee, who married Prince Stanislaus Radziwill, and Jacqueline, who, of course, became Mrs. John F. Kennedy). Because of his family background, it was often assumed that Vidal was affluent in his own right. He wasn't. He took a job as a copyeditor for E. P. Dutton, wrote screenplays for the budding new medium of television (one of which, Visit to a Small Planet, would later become a Broadway hit), and turned out a plethora of potboilers to pay the rent.

In the 50s, Vidal became a member of the new literary set—with Norman Mailer, Truman Capote, William Styron—and befriended Anais Nin, a middle-aged French writer who had been unable to get a book contract in America. She went on to become a feminist heroine with the publication of her multi-volumed diaries and Vidal was somewhat piqued that she never admitted the influence he had on her career and, in fact, snubbed him in her own works.

In 1960, Vidal made his only stab at electoral politics. He had written several books and had been on enough TV shows to gain a national reputation. He decided to run for Congress from New York State's 29th District, a Republican stronghold. He nearly won. And though he could have easily won a seat in the Johnson landslide of 1964, he declined to run—"I just couldn't relegate myself to the anonymity of the House of Representatives."

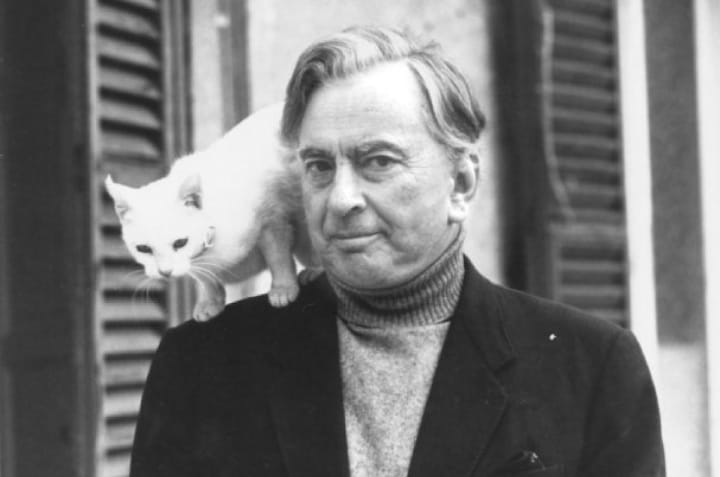

Photo via The Star

During the 60s, Vidal rose to preeminence among contemporary American authors. In addition, his play, The Best Man, was tremendously successful and became a hit movie. Virtually every book he turned out became a bestseller: Julian, Washington, D.C., and the controversial Myra Breckinridge, the story of a sort of American Gothic transvestite. Vidal's later book, Myron, is the story of Myra becoming masculated once more. "I'm the latter-day Mark Twain," boasted Vidal, only slightly tongue-in-cheek. "Myra is Tom Sawyer, and Myron is Huckleberry Finn."

Vidal was also one of America's premier essayists. His book, Homage to Daniel Shays, is a collection of 10 years worth of his essays. It is named after the leader of Shays' Rebellion, who, Vidal felt, would have plucked the United States from the clutches of George Washington, "America's first millionaire," had the rebellion been successful. "It’s dedicated to the road not taken," Vidal told interviewer Kelley.

Included in this collection was an essay attacking his in-laws and former friends, the Kennedys. A former intimate of Jack Kennedy (for whom, among other things, Vidal admits he served as an ersatz pimp, telling the president which Hollywood starlet he thought would be amenable to his amorous attentions), Vidal was appalled by Kennedy's term in office and what he saw as a potential Kennedy dynasty, with Bobby Kennedy succeeding his older brother, to be followed in due course by Teddy.

Vidal went on to spend much of his time in an Italian villa, journeying to America occasionally. Burr, Vidal's fictionalized biography of America's third vice-president, was last year's runaway best-seller, and Vidal is currently involved in turning the book into a five-part series for ABC Television. Although he lived on foreign turf, Vidal maintained that he was not an expatriate, inasmuch as he still payed American taxes and was one of this country's foremost critics. "Most of my time is spent commenting upon of thinking about America," he said.

His book titled 1876 is about Samuel Tilden and the Tilden-Hayes election of that year. To Vidal that election signaled the first wholesale selling of American democracy to the highest bidder. "It was the Watergate of its era," said Vidal, "and the story that Mark Twain tried to write, but couldn't."

Photo via Mubi

Penthouse: You've said that in publishing The City and the Pillar in 1948 you took on single-handedly the "American heterosexual dictatorship." Yet, by today's standards, it is rather tame. What was all the fuss about?

Gore Vidal: The only value of that book is that it was saying that the homosexual act has parity with the heterosexual act, and this was unheard of at that time—nobody would accept it. Homosexuals were criminals and/or insane, and there was no other position to be taken on the subject.

So although The City and the Pillar was melodramatic, to say the least, and very demure by today's standards, its assumption blew everybody's mind. I took a perfectly normal, all-American athletic stud and showed that he was wildly in love with his old boyfriend. It would have been all right if he were an interior decorator or a ballet dancer or a freak of some sort, but I used a dead gray style that sounded like James T. Farrell to make him seem like the boy next door. And, indeed, that's what the boy next door probably was up to.

Every man in the country knows this—or knew this. And yet this is the one thing he must never say—what buddies do on hunting trips. That's cheating. The fact that men in America are bisexual is a phenomenon that people just haven't confronted.

I remember when Adlai Stevenson was running in '52, Anaïs Nin said to me, "Of course, he's a homosexual." And I said, "What on earth makes you think that?"

"Well," she said, "because no heterosexual American man can have such wit or such charm."

And I said, "Do you realize that you've said the most devastating thing that I've ever heard said about the United States? That only a homosexual can have wit and charm?"

She said, "It's true." Whether it was true of Stevenson or not, I don't know.

Did you anticipate that the book would make the waves that it did?

Oh, yes. By publishing it was putting an end, I thought, to a political career—something that I wanted very much. In fact, not only could I not have a political career, I almost didn't have a literary career. Nobody would review me. So I vanished from sight, really, for quite a while.

But actually, even at sixteen I knew that was going to have to deal with this problem sometime—but I didn't know how I would deal with it and I didn't know that I was just going to come head on with an axe and take on the heterosexual dictatorship, which nobody had ever tried to do or dreamed of doing. That was a surprise and a slight variation from the script. But I did expect that there would be trouble. And it simply never occurred to me I'd ever lose. That wasn't part of it.

But you knew you were giving up any chance of becoming president.

Yes. I certainly wanted to be president, but I realized it was not in the cards. Before The City and the Pillar, I thought had a very good crack at it. But I turned it off. It was a decision done with open eyes. I knew that was eliminating something from my life that I might have wanted.

But in retrospect it makes no real difference one way or the other. So there have been many presidents, there's only been one me, one Hawthorne, one Whitman. All those presidents—think of that range of mediocrity!

At the beginning of his administration, you were hopeful that John F. Kennedy might be different—a fresh approach, rather than the same old mediocrity. What happened to change your opinion of him?

That was a curious piece, that first article I wrote on Jack, because I read it again about a year ago and I was rather startled at how wary it was. And how I struck the note that he might not live through his first term. I did think he’d die—terrible health would do him in or some angry husband would shoot him. Or else he’d be driven from office for moral turpitude. I was always positive something awful would happen to him of a sexual nature, though it never did.

Anyway, when I had my row with Bobby Kennedy, which was both personal and political, I saw that they were going to pass the presidency to Bobby after Jack had enjoyed two terms. I thought this was a bad idea. Bobby was really a child of Joe McCarthy, a little Torquemada. So I really was out to see that this didn't happen.

Moreover, Jack's presidency appalled me. He began with an invasion of Cuba that failed and he ended with the Vietnam War beginning. That was Jack Kennedy's contribution to American history.

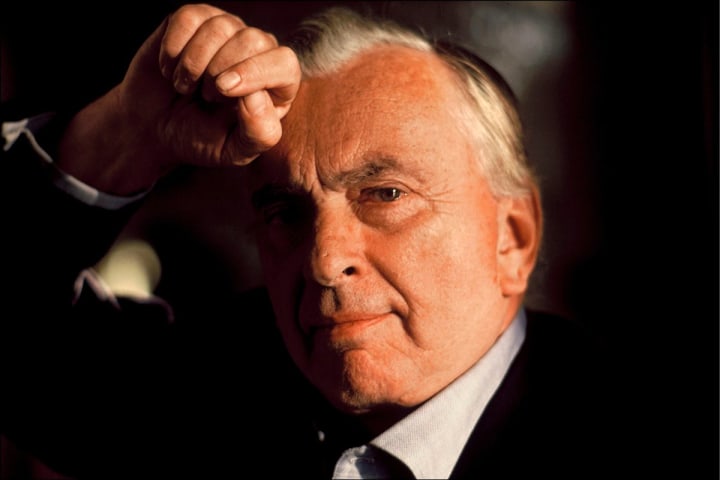

Photo via Democracy Now

You knew Kennedy personally. When he became president did you continue to call him "Jack" or did you call him “Mr. President"?

I called him "you." I couldn't call him "Jack" and I wasn't about to call him "Mr. President," so I said "you." It's funny—people always had to stand by and let him go into the dining room first. Everyone, even women, had to stand to one side as he went in. It was very royal, that place. Eleanor Roosevelt told me she went down and saw him right after he was elected, and he stepped aside for her to go through the door. She drew back: "Oh, no—you are the president."

He said, "I keep forgetting."

"You must never forget," she said.

One thing he never forgot was sex. He used to ask me about this girl and that girl. What was she like? Could it be arranged? He checked out everybody. He just went down the line. He was wild for Joanne Woodward. He knew that Joanne and Paul Newman and I were all living together in a house and wanted to know all about that. He said he found her very attractive and would like to meet her sometime. "Oh, come off it." I said. "She's all wrapped up in Paul."

"Well," he said, "what difference does that make?" He was very royal about those things.

And Jackie, of course, knew about it?

Yes.

Did she have any of her own trysts?

In the spirit of revenge, perhaps she might have. I wouldn't say if I knew.

What about injustice to homosexuals? Do you think the gay liberation movement is going to succeed in its revolt against the heterosexual establishment?

I think in the long run it will do pretty well. It depends on what the politics and the economy are like. These are far more important than the sexual climate. They should not be, but they are. If we have a dictatorship, which I rather suspect is in the cards, then we're apt to go through a great period of repression, sexual repression, which dictators need, particularly Protestant ones. But as things are going now, I think all the gay movements are slowly forcing the legislatures to change their laws, which is the most important thing to get done.

Do you think the cultivated androgyny of the rock 'n' roll culture has anything to do with it?

No, I think that reflects rather than inspires. It is a reflection of a general turning away from sexual roles. Also the tyranny of the female orgasm is really going to drive male heterosexuality to the wall. Because many men by and large cannot fulfill them—in many cases because it's not technically possible. Of course, before women found out about it, many of them were perfectly happy with their sex lives. Now it's, "Herman, are you giving me the Big O, are you a considerate person, Herman?"

"Well, Miriam, it has been two hours now, am still sawing away trying to give you the Big O."

"Well, Herman, I wonder if you're really a warm, mature human being; you're probably latently homosexual."

"It's been three hours, Miriam, three hours, I'm trying to give you the O."

"But if you were a warm and mature person, Herman, I would have had the Big O by now." This dialogue is heard every night in the suburbs of America. And one day Herman is just going to say, "Oh, shit. Here—take this vibrator, and I'll see you later."

Lots of male heart attacks are coming out of this, too. Men live under great tensions in the kind of greedy society that most of them have to work in, and now they also have to be good at sex and go on and on and on. I can see how a lot of them just quit the game and go with each other or stay alone.

More women are going with one another, too, they know all the buttons to push. They can get along quite well without that temperamental piece of meat which so often refuses to respond as Masters and Johnson would want it to. Moreover, I think homosexuality is somewhat simpler, in that it is a sort of doubling of one's own body, a mirror reflection of it.

When you go around speaking—to college audiences and such—what kind of reception do you usually get? Do cute little boys come up to you and offer their services for the night, as they offer them to Allen Ginsberg?

I fear that no ass ever comes my way on a lecture tour. For one thing, I'm too tired; for another, I'm rather intimidating. I think they suspect perhaps I don't love them—and this comes through, you see. Whereas Allen is in the business of dispensing love in great, great, great quantities along with the Oms. So we have a different audience.

How do you raise consciousness?

Well, I don't think of myself as being very effective, but I do things like talking about General Brown and West Point, which I think people ought to know. I hope that by saying the unsaid I make change possible, by opening people's minds to things they haven't heard or thought about. That's all.

But I suppose one could become a messiah that way. The field is wide open now. Everybody seems to be doing it; that mysterious Korean, the little fat boy from India... everybody's in the messiah racket. As the religions break up, all sorts of weird cults are going to come along. There's a fortune to be made in being the messiah. Give people faith and hope, give them something to live for. Tell them death is not the end. Read my novel, Messiah. Very prophetic.

Photo via The Daily Beast

Are psychoanalysts also in the "messiah racket"?

Psychiatry—like phrenology, which was very popular in the last century and was almost as highly developed a "science"—is just an anachronism. It is a manifestation of affluence for one thing; middle-class people with too much money wondering if they're being loved for themselves, as if there was much there to bother with, and as if there aren't plenty more where they came from.

The self-importance that analysis has given a handful of well-to-do people is an aberration. We're going back to real life very shortly. We're going to be starving to death and trying to survive.

So the works of such people as Freud and Jung, you believe, have no relation to “real life"?

Well, they're both interesting men. Freud, in fact, is almost good enough to be a novelist. He used the creative process properly. But it's all nonsense, of course—not to be taken seriously. His Leonardo is beautifully done. But you don't build a science on it.

Now Jung—Jung fascinates me. If I were ever to go mad, I might go mad in his direction—that is, if I ever took any of these gurus seriously. But Jung goes so quickly into fascism—blood consciousness, D. H. Lawrence, and the Nazis—that there's almost no time to enjoy the scenery. But much of it is charming.

It's much the same as believing in God. Our conceited notion that this dreadful race down here was created by something up in the sky that looks just like—guess who? Us! The silliest notion! Our self-congratulation is beyond anything.

Is humility a virtue?

I don't think it exists. We are born into a devouring world that eventually destroys us. Therefore our egos are naturally nervous and tend to voraciousness and self-centeredness, the very opposite of humility. Of course, you have professional religious people who affect humility—and a very gruesome sight it is. To see each of them trying to be more humble than the other is very chilling.

What about humility and the arts?

Not a useful pose, at least in America. To succeed in this country you have to continually tell people that you're the greatest this or greatest that. Otherwise they think, "If he doesn't think so, why should we?" Ours is a land of self-advertisers and snake-oil hustlers.

I've often thought that my literary reputation has suffered because I've never gone in for saying I'm the greatest this or the greatest that. My style tends to irony, to self-deprecation. This is totally un-American; They don't understand it. Why, I actually make fun of my own work, I've actually said some of it wasn't very good. Oh, they look very bleak at that because, they think, "If he thinks it's bad, my God, it must be simply terrible. He's some sort of bad person." You have to be continually in a state of euphoria and constantly boasting.

Much of this goes back to Hemingway. His was the first really diseased mind among the writers. He was a seriously mentally ill man who began a psychotic tradition that Mailer is now trying, without much success, to continue: Literature as a battlefield. Only one champ, Me Tarzan, you Jane.

You once said that we should not examine what people say about themselves but what their assumptions are about themselves. What do you think American's assumptions are about themselves?

Well, it's not their assumptions, it's what they don't say about themselves which is the giveaway; the things they do not examine. In politics, you have an endless list: Has anybody ever really brought up the fact that corporate profits continually get higher and higher as the economy gets worse and worse? Has anybody ever brought up the fact that we get nothing back for the taxes that we give to the government? America is the only country that gets nothing in return for taxes paid except the Pentagon. These are the unstated assumptions of the society. They are never brought up, they are entirely taken for granted and aren't challenged.

Who was our best president?

Well, Lincoln was our most interesting president. But he was a very difficult man and not at all as legend sees him. A very neurotic figure. The mystery of Lincoln is how a man with really no education, who was not much of a reader, could command the best prose style of any American. He writes better than any other American writer. How did he do that? He was wasted in the presidency because the South should have been allowed to secede. Oh, yes, we would have been better off. The whole problem of the American Empire was that we had to be this one indissoluble union marching forever westward and conquering the earth. It was an imperialist notion. Forget slavery—that was not an issue at all. That would have probably withered away in time. But there should be at least eight countries here, and if there were, we probably would be a much happier continent.

Then Lincoln made the biggest blunder of all.

Yes, but for the best of reasons. He was wrong: the South's case was perfect. They said they came into the union under their own free will and they always had every right to withdraw from the union. I think they were on strong constitutional grounds.

What was the greatest moment in your life?

Oh, my heavens, I suppose it hasn't come yet. It would have to do with power in some way—I suppose being president would do it. The most exciting moments are when I go on stage and there are 6,000 people cheering, I must say that. That gives me life, it's quite extraordinary. I just take energy from them—I'm a demagogue. Control over an audience is excitement like no other. I remember standing in an old auditorium in Boston which was packed with several thousand people and I was doing questions and answers. Somebody said, "How do you explain that Massachusetts was the only state to vote against Nixon in the last election?" And I said, "Well, I could flatter you and say that you were the Athens of America," applause begins, "but I'm not going to flatter you. All I'm going to say is that since the very beginning, this great commonwealth has been politically the most corrupt in the union and you know a crook when you see one." Well, I was nearly swept back to the proscenium arch. The applause started in the galleries, it went through the whole hall. It was like an explosion. And in a moment like that you think everything is working.

Photo via Note De L'Hotel

That's greater than any sexual pleasure?

Oh, beyond that, beyond sex. That's me and 6,000 people having an orgasm together. And you can't do it with 6,000 people in the usual way.

What was your greatest sexual fantasy when you were growing up?

Well, I suppose being president. That's the great turn-on! Two hundred and twenty million people, and I'm fucking them.

Do you still enjoy having sexual fantasies?

I don't seem to have very many now. I think whatever there is in the head has to be acted out, as much as one has the strength. But fantasy does play a great part in sex. The terrible thing is when you're in bed with A and you start thinking about B to get excited, because A isn't really turning you on. Then you're in bed with B and you start thinking about A to get excited. This is rather common and terribly depressing, too.

Of course, you solve it by going to bed with both A and B; but then you've committed the dread crime of troilism—an abomination in the eyes of man and God, three people in a bed.

Do you like orgies?

I used to like them, but you have to be in condition. You cannot be overweight. I am enough of a narcissist not to expose myself to an orgy without having been to the gym for at least a month.

You've said that to you sex is basically just an in-out ritual. Is there no mystique about it at all?

I once went to bed with a famous woman writer who said, "You fuck just like Picasso." And I said, "Well, I suppose I'm a genius too, aren't I?" She said, "I don't know about that, but it's just as boring." She said Picasso was on and then he was off, in no time at all, back to work.

Some people are like that and some people aren't, and since I'm not young and don't believe in giving pleasure to others, I don't believe you have to be GOOD at sex, all in capital letters. I've never had the anxiety that the culture creates about sexual performance. If it's lousy, it's lousy. I'm not doing it for them, I'm doing it for me. This is one of the reasons why I am such a champion of prostitution.

Besides, the working prostitute is just a more honest version of the usual thing of "all right, if you get me into the movies or take me to that glamorous party or tell me how wonderful I am for four days running, I'll give you my body on the fifth day." I'd rather spend $20.

Do you get lonely?

No. Never. As long as I have a book.

Do you get bored?

Not really, no. My energy drops and then I feel kind of exhausted, but I believe that's known as middle age.

Looking back on your career, what is the thing you're the proudest of?

Well, I don't know—I suppose the fact that I had a career at all. That I've done what I wanted to do. I'm not giving any aesthetic judgments on what I have done since I'm not my favorite writer, but given the cards was dealt in the way of talent, play them as best I can.

Recommended Reading

Gore Vidal's eclectic views and stories can hardly be covered in the course of one article. His books and the books that others wrote about him tell the complete story. To learn more about the writer's life and opinions, read the following volumes.

Myra Breckinridge is willing to risk everything to be superb and unique. Her primary goal is to prove to Dr. Montag that it is possible to live out all of life's fantasies and survive. "From Myra's fist appearnce on the page she was a megastar," explains Gore Vidal. Myra then reappears in Myron to battle with her alter ego.

Gore Vidal believed that there was no such thing as gay, only gay sexual acts. In Bed with Gore Vidal explores the truth about his sexuality, as well as its influence on his writing and public life. Tim Teeman interviews Vidal's friends and family to build an in depth portrait of the man.

Gore Vidal: Sexually Speaking dives into the engaging and often provocative sexual views of Gore Vidal. Fourteen essays and three rare, vintage interviews take on hot-button issues regarding the sexuality of government figures, church officials, and much more.

About the Creator

Filthy Staff

A group of inappropriate, unconventional & disruptive professionals. Some are women, some are men, some are straight, some are gay. All are Filthy.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.