Mom’s guy ran out of benzos, so I wanted to take Paul anywhere but back home after school. When her pills wore off, at best she’d run water over the soap bars to expose the listening devices she was convinced were hidden inside. At worst, she’d decide that Paul and I were minions of Satan sent to spy on her. Better for us to stay out of her hair, in case it went the second way.

Before school, she emerged from her bedroom in a discolored robe. She watched me zip the half-finished homework Paul had almost forgotten into his bookbag and she pointed with her cigarette. “Don’t forget your briefcase,” she told him, her voice less groggy than it had been for weeks.

Paul was actually better off leaving his miniature plastic attaché of comic books at home — a thing like that could get an 11-year-old in trouble at school with teachers and bullies alike. But I wouldn’t press Mom about it. She had that funny look in her eyes she got sometimes when she came down off tranquilizers; a wicked sparkle that warned me that a disturbing incarnation of her paranoia might come out, one that centered on what profane creatures we were.

High school let out before middle, so I’d walk across the street after the last bell and wait for Paul every day. To my relief, my little brother, shoelaces now loose and hair cowlicked from leaning his head on the desk, still swung the orange briefcase in one hand as he ambled out of the middle school. Sometimes we had to go back in for it.

He adored comic books and we both hated for him to spend even one night without the collection, with nothing for him to disappear into. If our mom got hold of her pills, he might not need it. We might have a peaceful evening watching M*A*S*H* and Match Game on our 12-inch black-and-white TV while Mom slept.

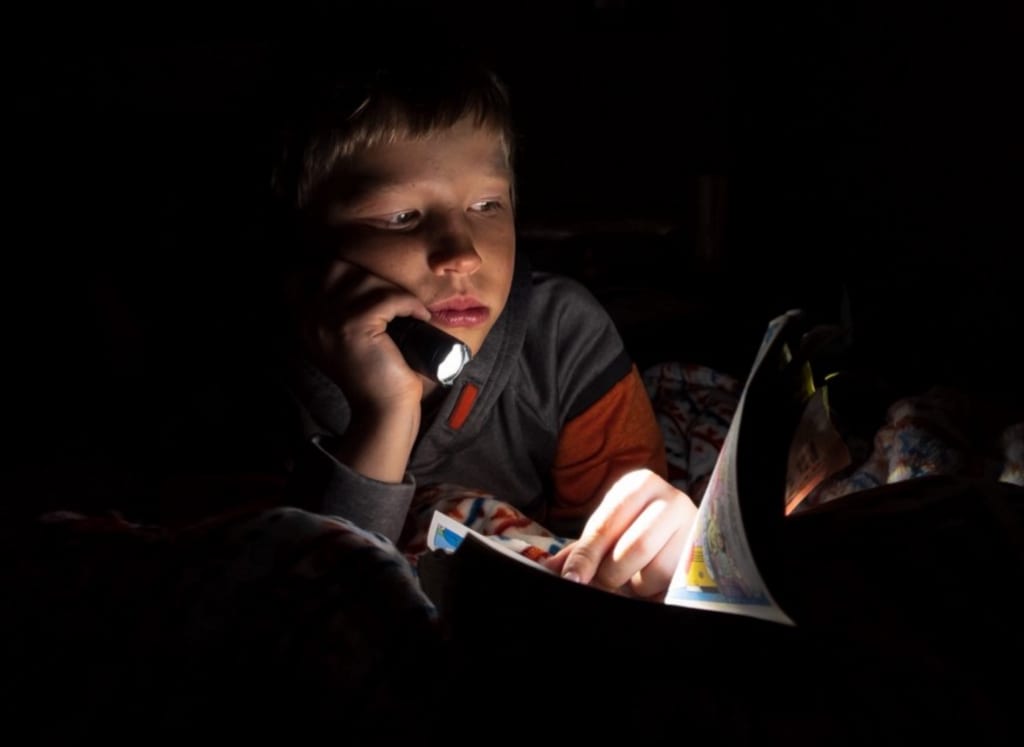

But if she didn’t, anything could happen. Even when she only paced around rattling off angry, repetitive prayers, Paul would squeeze himself into the tiny hall closet with his case of comics nestled against his stomach, an open issue on top. I’d peek in sometimes to check on him and he’d whisper up at me, “Did you know, Spider-Man changes the chemicals in his webs so he can wrap them around his fists and punch Electro without getting shocked?”

“You want to go to 7-Eleven, read comic books?” I suggested.

“Yeah,” he said. “But they won’t let me.”

It was true, when Mom sent us for cigarettes and Paul tried to camp out next to the magazine rack, the clerks at 7-Eleven would yell at him: No reading without buying!

“We’ll go to the one on the boardwalk.” The opposite direction from school as home, they didn’t know us at that 7-Eleven. Plus, I wanted to watch the ocean for a while.

It was late into autumn, but some of the stores on the Atlantic City boardwalk stayed open past summer that year. The Resorts International Casino had just opened earlier that year, and legalized gambling attracted tourists to this beach town months after bathing suit season ended. Still, Paul and I were the only people around in front of the 7-Eleven.

I leaned over the boardwalk’s rail. I liked the beach, and to watch the ocean. Didn’t much care for sand and I wasn’t a strong swimmer, but from a scant distance, with my feet planted on solid wood, the ocean’s rhythmic, hypnotic roar unseated the chatter of anxiety that usually filled my head. I closed my eyes, listening, and my breathing came easier, the nippy November air sharp and pleasant in my sinuses like a strong mint.

“C’mon,” Paul whined, rubbing his ungloved hands together. “It’s cold.” I turned toward the 7-Eleven and my regular anxious hum returned.

The door jingled as we entered and the clerk glanced away from his tiny TV on the counter long enough to nod at me. Paul slid past him to the magazine rack, picked out The Amazing Spider-Man, and rested his briefcase on the floor to thumb through it.

I checked the clerk for signs of annoyance, but found nothing to indicate he felt any. His focus was on the TV, which showed a still image of happy hippie types. Unhappy men’s voices droned over it.

“You see this? They’re saying 900 deaths now,” the clerk said.

I didn’t follow the news. For the longest time growing up, it was all Watergate and Vietnam. It bored me and riled Mom, so I’d kept avoiding it long after Nixon had gone.

“Deaths? From what?”

“That cult from California in Guyana. Who killed a congressman and then drank poison.”

I was 15 and except for “killed” and “drank poison,” those words didn’t mean much to me. “Congressman” sounded like history class, both “California” and “Guyana” a whole other world from New Jersey, and “cult” a chilling sliver of a word.

“What’s a cult?” I asked.

He shrugged and turned the volume up. A somber newscaster spoke over images of dead bodies lined up in neat rows.

…Jones had become more and more paranoid, which shifted the focus of the People’s Temple away from spiritual matters and toward infighting. The paranoia fed off itself and tensions within the group escalated…

I only understood every other word, but I got it exactly. The leader, Jim Jones, ordered his followers to drink poisoned Kool Aid, the same sweet drink powder our mother would buy for us in her happier moments, as a treat. They made the children drink the concoction first. Anyone who refused, they shot. They even poisoned the dog.

I pictured my mother stirring a cup for us, her spoon knocking against the sides, the powder dissolving in Technicolor red.

After a minute, Paul’s attention shifted to the television as well. He stared at the screen, transfixed. “Some people ran through the jungle, though. They got away,” he said. It was the only thing he said about it. He kept watching until the information only repeated itself, then returned to his comics.

The sun set in the late afternoon and we stayed another hour after that. Some loud drunk customers came and went, and in the striking silence that followed, the clerk acknowledged us again. “It’s dark out,” he said.

I took the hint. I bought a bag of chips for Paul with a dollar I’d been saving in my backpack pocket. Nothing for me — I ate very little in those days, but I made sure Paul got something to eat. He munched as we meandered a circuitous route, choosing streets I deemed “safer” among Atlantic City’s garbage and riffraff and the urban chorus of nearby sirens.

Those sirens grew louder when we rounded the corner to our apartment complex. Though part of me always half-expected to come home to a horrible scene, the active fire and blinding red trucks lined up in front of our home still knocked me back like a sucker punch. An ambulance pulled forward, urging dispersal of the crowd of people that gathered around, pointing and talking animatedly to each other.

With rising panic, I checked from face to face for Mom, but did not find her. A sick feeling gathered in my gut as it dawned on me that the flames that poured from the building came strongest from our own apartment’s broken windows.

It’s hard to remember, but I think I began screaming until the cops told me to stop. After that, I went mute.

A rush of activity blinked around us, then Paul and I found ourselves placed in the back of a social worker’s sedan. We stayed perfectly silent, more ghosts than children. Then, through the thick haze that fogged around me like I’d swallowed one of Mom’s pills, an urgent thought struck me: the briefcase!

“We left something important at the 7-Eleven on the boardwalk,” I wailed out of nowhere, startling the social worker. The tears I’d held back burst out in a frenzy. “Paul needs it!”

She checked her watch and clicked her teeth, but I’d roused her pity. She made the detour.

After that car ride, without Mom’s terrible gravity pinning us down, we’d be set loose in the jungle. We’d get placed in foster homes, switch schools, probably. They might even separate Paul and me. I leaned forward to direct the woman down the quickest cross-street, urgently as though pointing more strenuously would prevent Paul’s most prized possession from vanishing like everything else in his life.

The orange suitcase flashed bright as a rising phoenix against the cardboard tones of 7-Eleven’s lost-and-found box. I pounced on it before the clerk had even set the box down on the counter.

“Hold tight to this, don’t lose it,” I bade Paul to promise. I pressed the case hard into his listless right hand. “No matter what.”

His eyes barely focused on me, but his arms moved automatically to nestle the plastic safe against his stomach, his closet posture.

I couldn’t protect him beyond this. Spider-Man had better step in.

About the Creator

Lissa Bay

Lissa is a writer and nanny who lives in Oakland, California. She enjoys books, books, playing Disney songs on ukulele for kiddos, books, and hanging out with her deeply world-weary dog, Willow. And, oh yeah, also—get this: books.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.