‘Nobody can hear a scream in the vacuum of space, or so they say. Despite this mathematical certainty, I have indeed reckoned the roar of a passing Vermeer missile on its course to an adjacent star system. I jest, though the sheer tumultuary presence one feels passing such a thing… it’s truly astonishing. Especially considering the speed; watching that dart race past, knowing its target is over eight years away…’

Dr. Havenshire drawled his babble, actualizing his spokesman training with rote-like efficiency. Had his listener been a tourist, or perhaps the investor-type he was truly designed for, there’d be no doubt in his succession, and even his docility. Redrick watched him, the childish face with rakish glasses and an askew glance; when not speaking his lips would thinly part and he’d sit prostrate, like an idiot. There was a large incision running the length of his right hand, which he often itched. Havenshire looked, in the face, the part of a typical scientist: a face normally pale yet quickly turned scarlet, with a high-arch nose and remnants of a shadow on his jawline; he enunciated his words with especial import.

‘He considers Earth a holiday,’ observed Redrick, noting the leisurely attire.

In truth, there was great difficulty in listening to the wiry man, such was a commotion outside Red’s current environment – the General’s office – and so filled with questions that he sat uncomfortably and with a degree of caution. Havenshire picked on this:

‘Are you okay, Redrick? You look a little pale.’

‘Yeah,’ he began, unsure, ‘yeah, though I get a little claustrophobic in a place like this, y’know?’

Havenshire whistled, ‘damn. That’s gotta be tough on a spacer.’

‘Actually, I’m not a spacer. Born on Earth.’

‘Oh wow!’ Havenshire started, with a fresh alacrity, ‘oh wow indeed! Don’t see many of you nowadays. From Mars myself…’ he trailed off.

Not once had the General looked up from his papers, his forehead was creased in concentration.

‘I’ve been there,’ said Redrick, ‘not heaps, but there’s some nice towns and such.’

‘Nice towns and such, yes yes…’ Havenshire echoed, ‘you know there’s this special type of animal there, I don’t know how to describe it exactly… kind of like a jackal but no hair, and walks on two legs… couple feet high?’

‘Never heard of it.’

‘Well, you must get some sent to you, cooked I mean, it’s a favourite of mine and my family’s.’ Havenshire stopped momentarily to shift positions in the seat, resting his head in the weak tenure of his arm, ‘although, I ain’t much a fan of space food myself. It’s just a little… I don’t know…’

‘Aged?’ Redrick interjected, the constant stopping and starting was starting to annoy him.

‘Yeah… yeah, that’s a good way for it. But to have a home here on Earth, that’s quite amazing. It’s--’

‘Gentlemen.’ He was cut off by the general. A thick, stocky man of good breed, with large, round shoulders and a chiselled face, General Marwen reeked the excess diplomacy and military conjunction required of a man of his position. His colourless, somewhat messy hair, parted down the middle, framed his grizzly cheeks in a way that kept Redrick looking intensely at them. His uniform hung awkwardly on him and looked like a fetter that now lay heavily on his back. His eyes, though a crystalline blue, were ringed in black and had a sunken, hollow appearance. Redrick figured him somewhere over fifty.

‘Gentlemen,’ he continued, looking past both his companions, ‘firstly, I apologise for the abruptness, namely, to your holiday, Captain.’

‘Don’t mention it, Sir.’ Redrick replied.

Marwen had volumes of white paper between his fingers and seemed to be caught between his guests and the work. For a while, he sat without stirring. Though often good-natured and approachable enough, today he displayed a grim demeanour, and seemed not pleased at his circumstances. Still, the curiosity gnawed at Redrick, and even in the midst of this airlessness, he managed to summon the first word.

‘May I ask, Sir, as to why there is so much commotion out there?’

Marwen looked directly at him, intensely so. ‘Oh, that. Yes, well that is indeed partially the reasoning for your arrival. Have you ever seen,’ this he directed to Havenshire, ‘have you ever seen such babble down here?’

He shrugged. ‘Can’t say so Burt, no. Though worse has happened, I guess.’

‘Regardless, it is serious, though half these halls are crammed with – you saw them, Red – kids! Old enough to get a piece of paper tellin’ you can fly to Saturn, young enough to worry about their girlfriend’s goin’ with ‘em.’

Marwen stood, flexed his joints, and stepped languidly to the window. The asphalt of the airfield was steaming in the sun, the blossoms on the grasses’ border had fallen off; the corner of the window crackled with static. Marwen squinted at the discrepancy and flicked a few fingers on it, then a whole fist. The picture fuzzed back to normalcy, and resuming his passive gaze, turned around to Red again.

‘About fourteen hours ago, a missile struck near a base on Triton.’

Redrick’s eyes widened. Havenshire looked unfazed, almost pleased to witness the news being broken to someone for the first time.

‘Triton?’ Redrick replied, ‘that’s impossible.’

‘Impossible? Doctor?’

‘As I was just reassuring the general,’ said Havenshire, lightly, ‘there is no impossibility in that regard. In fact, launch anything in space, the chance of it never hitting another object is quite the impossibility. If this was calculated, as fits the pattern, then we count our graces it did not in fact hit the base. Although, I’m unsure there even was a base established on Neptune or its surroundings when that missile first launched, which theoretically should have been around eight years ago.’ He interrupted himself in his own excitement, removing his glasses to stare at Red with myopic eyes. ‘Now, I ain’t a psychic Redrick, but that Vermeer missile – my design, by the way – will hit a target, there’s no mathematical reason why it shouldn’t.’

There was a faint emphasis hidden in Havenshire’s words that disturbed Redrick, partially because he seemed to relish keeping the minutiae details secret; and, more importantly, because one doesn’t bring the progenitor of interstellar war to a meeting unless you plan to up the ante. Marwen inspected the doctor with a glazed eye and polite smile.

‘Neither Red nor myself are much of logistics men, I’d appreciate it if you gave the details pertinent to us.’

‘Of course, Burt. Do you know, Red,’ he began again with increased zeal, ‘about anchor stations?’

‘Of course,’ replied Red, ‘stations placed in strategic sections of space around and within Sol, designed to detect incoming foreign objects from Alpha Centauri, track its trajectory, and warn the potential fallouts of a strike.’

‘And this means--‘ prodded Havenshire.

‘I’m not sure I understand.’

He sniffed and emitted a whooping sound of laughter. ‘It means, Captain, that any object sent from our adversaries in Alpha Centauri are yet to learn of their existence, otherwise they would just wipe them out with a single, calculated strike, and send a wave of missiles in all stretches of Sol!’

Marwen scowled and broke in: ‘Actually, there’s a mathematical impossibility for you. No one could produce that many weapons in a million years, let alone sixty.’

Havenshire scoffed and said dryly: ‘A hypothesis, Burt, nothing more. But listen to this…’ he leaned forward till he was but a murmur’s pace from Redrick. The general leaned in closer too. ‘what if I told you, despite my boasting and theatricality just before, that we (and by we, I mean Sol and Alpha Centauri) are actually just shooting from the hip? All the peppy hogwash we drivel out monthly to you spacers, about how we know enemy locations and such, and can wipe them out, slowly but surely, with no loss of human life, it’s all false.’

‘That’s not necessarily true…’

‘You’re right, of course. But every day, it becomes more so. And this is why those anchors are so damn important. We don’t know the enemy, and they don’t know us. This is not a war of attrition, but one of time. The victor is determined in two ways.’ Havenshire fingered a pipe, which Redrick hadn’t noticed before, and held up two fingers with his other hand. ‘One: Whomever first builds missiles that fly faster than the speed of light. Two: Whomever first learns the enemy planets, positions, and peoples as soon as they are erected.’

‘For your hypothesis’s sake,’ Marwen interposed, ‘which of those two possibilities is most likely? At least in the immediate future.’

‘The immediate? Well, any solution is unlikely to be in the immediate, at least for us. But that is beside the point. An enemy like those in another star system, seemingly on a similar developmental path as us, may stumble on either option first. And do you suppose, following that logic, they have not considered the same outcomes?’

‘Which is why we need the anchors.’ Redrick stated.

‘That’s right, Red.’ He said, smiling, ‘those stations give valuable time we need to find our solution, which cannot be measured in the years… perhaps the decades, likely the centuries.’

Redrick slanted back in his seat, he knew where this was going. ‘A station failed to report the incoming missile, didn’t it?’

Marwen was back at the desk, picking up the papers and straightening them for show, then rifling through them again to pick a specific paragraph. ‘four hundred and thirty-nine stations reported—’

‘Out of a possible four hundred and forty.’ Said Havenshire.

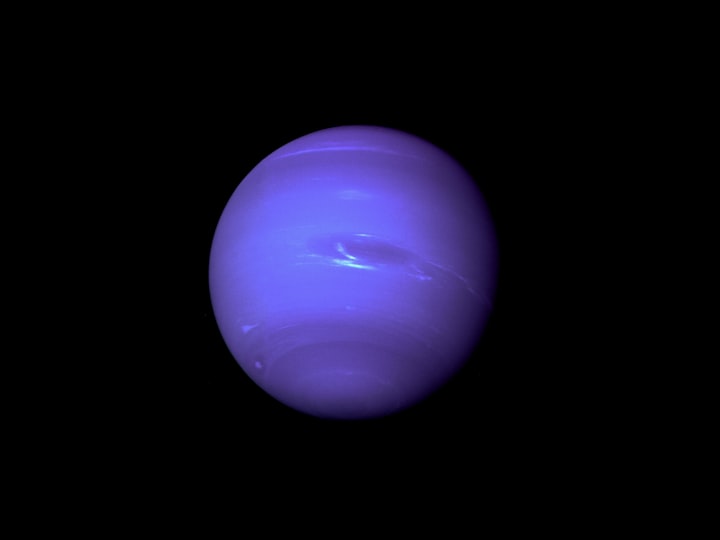

Redrick detected a strange pronouncement of the general’s voice in the last instant, possibly of fear or shame. His face was downcast in the papers and was the colour of a morning fog. He did not engage with Redrick immediately, letting out a deep sigh before sliding a document in his guest’s way. It was a schematic drawn in beautiful articulation, (clearly not human) featuring the backdrop of a massive blue planet – likely Neptune – with the clearly incongruous outline of an anchor station in the foreground. The bold title at the top: The Mortimer.

On the backside was an enlarged view of the station, criss-crossed with lines, nodes and notations detailing the primary external functions. While exceptionally presented, Redrick saw nothing extraordinary in its detailing.

‘Is this recent?’ he asked.

‘No,’ replied Havenshire, ‘though it hardly matters, there may be some extra bits on here and there, but inconsequential.’

Redrick considered his face carefully, his smooth face seemed remotely vexed.

‘The situation suddenly weighs on him,’ Redrick observed, ‘perhaps there is more to this station than he’s letting on.’ He felt a twinge in his jaw and opened them half an inch behind closed lips. Then he studied Marwen, whose face remained stern.

‘Well, if a station doesn’t report in, I imagine you send a message back to ‘em, yes?’

‘Normally yes, in a matter of a few hours,’ Marwen noted, ‘depending on the station, of course. And we did just that, Red.’

‘And no response?’

‘None, but I guess that wasn’t too unexpected.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because, Redrick,’ Havenshire suddenly crossed, ‘the Mortimer is one of our first anchors. At least three generations have spawned there since its first operation. There are likely more civilians than soldiers, and you know how that messes with the hierarchy of command, yes? It’s not too preposterous to assume the civilians have instituted a micro-government, or something of the sort. It’s easy to forget, you too Burt, that in a war with zero casualties, friendly or enemy, that a war indeed exists. There’s no great wisdom in their position; maybe they got bored, figured the people of a planet six hours away ain’t matter anymore. And do we matter that much? They get an automated supply ship once every three months, and that’s it.’ He paused momentarily in a trifle of doubt. Standing, and crossing to the window, he too looked indirectly out at the airfield. At that instant, there was a decrepit silence in the room.

‘They got families, too.’ Marwen finally spoke morosely.

‘Yeah… that too.’ Havenshire replied.

‘So… you want someone to go there…’ Redrick said, complacent.

No one seemed to notice his statement, but there was a general stir of understanding. ‘Can you believe, Red, that wars used to be fought and won in only a few years? Maybe ten at the most?’ Havenshire chuckled, clinging his pipe to his chest and shaking the general’s hand – all seemed well in war today.

Comments (1)

Fantastic idea. Great premise. Very creative and enjoyable. Keep up the good work.