The Egg

Don't count your chickens until they are hatched

I have no doubt that my father was born to be a happy, caring person. He worked as a farmhand for Thomas Butterworth, whose property was close to the Ohio town of Bidwell, until he was thirty-four years old. He drove into town on Saturday nights with his own horse at the time to engage in some social interaction with other farm workers. He drank three glasses of beer in the city while loitering in Ben Head's bar, which was frequently packed on Saturday nights with travelling agricultural labourers. Glasses banged on the bar as songs were sung. Father drove home at ten o'clock over a lonely rural road, prepared his horse for the night, and then retired to bed, content in his place in life. At the moment, he had no intention of attempting to advance in society.

Father married my mother, who was a country schoolteacher at the time, in the spring of his 35th year, and the following spring I was born writhing and inconsolable. The two people experienced some sort of event. They developed ambition. They were possessed by the American desire to wake up and change the world.

It's possible that mum was to blame. She had no doubt read books and publications because she was a teacher. She may have imagined as I lied next to her throughout the days of her lying-in that one day I would rule over men and cities because, as I assume, she had read about how Americans like Garfield, Lincoln, and others climbed from obscurity to renown and glory. In any case, she persuaded father to quit his job as a farmhand, sell his horse, and start his own independent business. She was a large, mute woman with troubled grey eyes and a long nose. She had no wants for herself. She had an unquenchable desire to succeed for my father and Myself.

The two people's initial business venture didn't go well. They began farming chickens after renting ten acres of subpar, stony terrain on Griggs' Road, eight miles from Bidwell. I developed into a boy there and formed my initial opinions on life. They gave off the feeling of calamity right away, and if I, in turn, am a sombre man inclined to see things negatively, I blame the fact that I spent what should have been my happy, carefree youth years on a chicken farm.

Uninitiated people may not be aware of the numerous sad things that can happen to a chicken. It emerges from an egg, grows to be a tiny fluffy creature similar to what you see on Easter cards for a few weeks, then turns hideously naked, consumes a lot of corn and meal that your father paid for out of his own sweat, contracts diseases like pip and cholera, stands in the sun gazing stupidly, falls ill, and eventually dies. A few hens, and perhaps a rooster, struggle to adulthood in order to fulfil God's inscrutable purposes. The awful cycle is completed when the hens lay eggs, which hatch into more chickens. All of it incredibly complicated one step ahead in life assessments.

The majority of philosophers must have grown up on farms with chickens. One expects so much from a chicken and is so utterly let down. Little hens who are just starting out in life appear so alert and brilliant, but in reality, they are painfully stupid. They resemble people so closely that one can confuse them when making judgements about life. If illness does not claim them, they wait until you are thoroughly aroused before walking under a cart to be crushed and killed before returning to their creator. Their youth are infested by vermin, necessitating the purchase of expensive powder remedies. Later in life, I became aware of the literature that has developed around the idea of making fortunes of the chicken-raising process. The gods who have just consumed fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil are supposed to read it.

It claims that simple, ambitious folks who possess a few chickens may accomplish a great deal. Don't let it mislead you. Not for you, it was not written. If you want to believe that the world is getting better every day and that virtue will ultimately triumph over evil, go prospect for gold on Alaska's snowy slopes, have faith in a politician's honesty, or anything else, do not read or believe the literature about the hen. Not for you, it was not written.

I'll stop there, though. My story is not primarily focused on the hen. If told appropriately, the egg will be the focal point. My mother and father toiled for ten years to make our chicken farm profitable before giving up and starting over. They settled in the Ohio town of Bidwell and started a restaurant. After ten years of stress over incubators that did not hatch, tiny—and in some ways lovely—balls of fluff that developed into semi-naked pullethood and then into dead hen-hood, we set everything aside and drove down Griggs's Road towards Bidwell in a tiny caravan of hope in search of a new location from which to embark on our journey.

We must have appeared dejected, not unlike refugees fleeing a war zone, I imagine. I walked in the road with my mother. Mr. Albert Griggs, a neighbour, had let us borrow his cart for the day, which was loaded with our belongings. A crate containing live chickens was behind the stack of beds, tables, and crates containing culinary equipment. On top of that was the baby carriage that I had been dragged around in as a baby, and out of its sides protruded the legs of cheap chairs. I'm not sure why we insisted on using the baby carriage. The wheels were broken, and it seemed unlikely that any more children would be born. Individuals with limited goods hold on to them dearly.

The father sat atop the cart. He was then a balding, slightly overweight man in his forties who had grown accustomed to remaining silent and dejected due to his extended contact with his mother and the hens. He worked as a labourer on neighbouring farms for the entirety of our ten years on the chicken farm, and the majority of the money he earned was spent on treatments for chicken diseases, such as Wilmer's White Wonder Cholera Cure, Professor Bidlow's Egg Producer, or other products that mother discovered advertised in poultry publications.Just above his ears, father's head had two tiny hair patches. On Sunday afternoons in the winter, I recall that as a young child, I used to sit and observe him as he dozed off in a chair next to the stove. I had just started reading novels and forming my own ideas at the time, and I imagined that the bald trail leading over the top of his head resembled a vast road, similar to one that Caesar would have built to take his soldiers out of Rome and into the wonders of an uncharted world. I compared the hair tufts that developed over my father's ears like forests. I awoke from a dream in which I was a tiny creature travelling along a road into a stunning location devoid of chicken farms and where life was a joyous event without the consumption of eggs.

Our journey from the poultry farm to the city could be the subject of an entire book. Together, my mother and I walked the entire eight miles—she to make sure nothing dropped off the waggon and me to take in the sights. Father's most prized possession was sitting on the wagon's seat next to him. I'll let you know about that.

Surprising things occasionally occur on a chicken farm when hundreds or even thousands of chicks hatch from eggs. Eggs give birth to grotesques just like people do. The accident only happens occasionally—possibly once every a thousand births. You see, a chicken is born with four legs, two pairs of wings, two heads, and other features. The objects are not alive. They swiftly return to the hand of their creator, which had briefly trembled. One of the sorrows of fatherhood was that the poor little things were unable to live. He believed that his fortune would change if he could only raise a hen with five legs or a rooster with two heads make it. He imagined bringing the marvel to county fairs and becoming wealthy by showing it to other farmworkers.

The little hideous creatures who were born on our chicken farm were all saved, at least. They were each placed in a glass container and preserved in alcohol. These were carefully placed in a box, which he carried on the waggon seat next to him as we drove into town. He held on to the box with one hand while using the other to drive the horses. As we arrived at our destination, the box and bottles were immediately taken down.The grotesques in their tiny glass bottles sat on a shelf behind the counter for the whole of our time as the restaurant's keepers in the Ohio town of Bidwell. Mother would occasionally object, but father never wavered when it came to his treasure. He said the grotesques were priceless. He claimed that people enjoyed looking at unusual and fascinating objects.

Did I mention that we started our restaurant venture in the Ohio town of Bidwell? I slightly overstated. The actual settlement was situated next to a tiny river and at the base of a low hill. The railroad did not pass through the town; instead, it stopped at a location called Pickleville, one mile to the north. At the station there had once been a pickle plant and a cider mill, but by the time we arrived, both had closed. Buses left the hotel on Bidwell's main street and travelled along Turner's Pike to the station every morning and every evening. Mother had the idea that we should start our restaurant business in a remote area. After discussing it for a year, she finally decided to rent an empty storefront next to the railroad station. She thought the restaurant would be successful. She claimed that travelling men would often line up at train stations to board departing trains while residents of the town would gather there to wait for arriving trains. They would frequent the eatery to purchase pies and drink coffee.I realise now that Mom had another reason for attending as I have grown older. For me, she was ambitious. She wished for me to advance in life, enrol in a local school, and mature into a man of the community.

Father and mother put in long hours at Pickleville like they always had. At first, it was necessary to transform our space into a restaurant. That required a month. Papa constructed a shelf on which he placed vegetable cans. He painted a sign and wrote his name in big, bold red characters on it. His name was followed by the direct order to "EAT HERE," which was not often followed. Cigars and tobacco were placed into a display case that was purchased. Mother cleaned the room's walls and floor. I attended school in the city and was relieved to leave the farm and the sad, dejected-appearing poultry behind. I felt like I was acting in a way that should not be carried out by someone like myself who grew up on a poultry farm where death was a frequent visitor.

I was still not overly happy. As I made my way along Turner's Pike home from school in the evening, I thought back to the kids I had seen having fun in the town schoolyard. A group of young girls had ventured out while bouncing around and singing. I gave it a go. I hopped gravely along the icy path while standing on one leg. I shrilly sang, "Hippity Hop To The Barber Shop." After that, I halted and took a cautious glance about. I was worried that my gay mood would be noticed. I must have felt that I was acting in a way that someone who, like myself, had grown up on a poultry farm where death was a daily visitor, shouldn't have acted in.

Mother made the decision to keep our restaurant open late. A passenger train and a local freight passed our door at ten in the evening. After finishing their work in Pickleville, the freight crew stopped by our restaurant for hot coffee and meals. One of them occasionally placed a fried egg order. About four in the morning, they left us and came back in the direction of the north. A small business started to develop. While father slept, mother took care of the restaurant and served our boarders during the day. He slept in the same bed that my mother had used as I left for school in the town of Bidwell. In the lengthy father prepared the meats for the sandwiches that would be included in our boarders' lunches at night while my mother and I slept. Then he had the thought to stand up and face the outside world. He became possessed by the American spirit. He developed ambition as well.

Father thought it would be a good idea for him and mom to try to amuse the diners at our restaurant. Although I can't recall his exact comments right now, he gave off the vibe of someone who was ready to emerge as a sort of obscure public performer. Bright, enjoyable talk was to be had when visitors visited our property, especially young people from the town of Bidwell, which happened on very rare occasions. I inferred from my father's statements that the jolly innkeeper effect was something that should be aspired after.Mother must have had reservations from the beginning, but she made no demoralising comments. Father believed that the younger residents of the town of Bidwell would develop a strong need for his and mother's presence. Bright, joyful groups would start singing down Turner's Pike in the evening. They would march into our area shouting and laughing. There would be music and celebration. I didn't want to imply that father discussed the subject in such detail. He was, as I've stated, a man who didn't like to talk. "They desire a destination. I can tell you that they want to go somewhere "He repeatedly said. He only advanced as far as that. The gaps have been filled in by my own imagination.

This idea of a father infiltrated our home for two to three weeks. We didn't converse much, but we made an effort to replace gloomy expressions with smiles in our regular interactions. Mother grinned at the guests, and I grinned at our cat as I began to feel sick. In his desire to please, Papa grew a touch heated. There was without a doubt a little of the showman's energy inside of him. He did not use much of his ammunition on the railroad workers he looked after at night; instead, he appeared to be watching for a young person from Bidwell to enter so he could demonstrate his skills. There was an always-filled wire basket on the restaurant counter and it must have happened right before his eyes when the notion of being amusing first entered his head.The way eggs continued to be involved in the growth of his concept had a prenatal quality to it. In any case, an egg shattered his newfound life purpose. One late night, my father's throat let forth a roar that woke me up. Mother and I were both sitting straight in our beds. She lit a lamp that was on a table beside her head with shaky hands. Our restaurant's front door shut with a loud crash down below, and dad soon started trudging up the steps. His hand, which was clutching an egg, shook as if he were experiencing a chill. His eyes had a half-crazy gleam to them. I was certain he was going to throw the egg at either my mother or myself as he stood there gazing at us. He got on his knees next to his mother's bed and carefully placed it on the table next to the light. He started sobbing like a little boy, and I was overcome by his sorrow and wept alongside him. We both screamed in unison, filling the little upstairs room. It's absurd, but the only thing I can recall about the picture we took is that my mother's hand kept stroking the bald patch across the top of his head.I can't remember what his mother said to him to get him to tell her what had happened below. My memory of his reasoning has also faded. Only my own sorrow and fear come to me, along with my father's shiny path over his head that shone in the lamplight as he knelt by the bed.

About what occurred downstairs. For some reason I remember the incident as vividly as if I had actually seen my father's discomfort. Over time, one learns a great deal of mysterious things. Young Joe Kane, a Bidwell merchant's son, travelled to Pickleville that evening to meet his father, who was scheduled to arrive from the South at ten o'clock. Joe came to our house to laze around while we waited for the train, which was three hours late. The freight crew was fed as the neighborhood freight train arrived. Joe and his father were left alone in the restaurant.

The Bidwell young man must have been perplexed by my father's actions from the moment he entered our home. He believed that his father was upset with him for loitering. He pondered about leaving when he saw that the restaurant manager appeared to be upset by his presence. He did not relish the lengthy trip to town and back, though, as it started to rain. He placed a coffee order and made a five-cent cigar purchase. He pulled out a newspaper from his pocket and started reading. "The evening train is what I'm waiting for. It is late "He apologised, he said.

Father, who Joe Kane had never met before, stared at his visitor in silence for a considerable amount of time. He was undoubtedly experiencing a stage fright attack. He had thought about the issue in front of him so much and so frequently that, as is so common in life, he was a little uneasy in its presence.

He was clueless about what to do with his hands, to start with. He cautiously pushed one of them across the counter to shake hands with Joe Kane. How do you do, he said. Joe Kane set down his newspaper and fixed his gaze on him. Father started to speak after his attention caught the egg basket on the countertop. Oh, you have heard of Christopher Columbus, eh? he said hesitantly. He appeared to be furious. He said emphatically, "That Christopher Columbus was a cheat. "He mentioned turning an egg on its end. He spoke, acted, and after that he went and cracked the egg's end."

To his visitor, my father appeared to be inconsolable at Christopher Columbus' deceit. He grumbled and cursed. In his opinion, it is improper to have students learn that Christopher Columbus was a great man because, after all, he cheated when it mattered most. He had bluffed that he could make an egg stand on end, and when his bluff was called, he pulled a fast one. Father picked an egg from the basket on the counter and started to walk up and down while still complaining about Columbus. Between the palms of his hands, he rolled the egg. He gave a friendly smile.

He started to murmur some things about the effect that the electricity that emanates from a human body would have on an egg. He claimed that he could hold the egg on end without cracking the shell and by rocking it back and forth in his palms. Joe Kane showed a hint of interest as he continued by explaining how the egg's new centre of gravity was generated by the warmth of his palms and the gently rolling motion he gave it. Father answered, "I have handled thousands of eggs. Nobody is more knowledgeable about eggs than I am.

The egg dropped on its side when he placed it on the counter. He repeated the trick numerous times, rolling the egg between his palms while uttering proclamations about the wonders of electricity and the rules of gravity. When he finally managed to get the egg to stand after a half-hour of labour, he looked up to discover that his visitor had left. By the time he was able to alert Joe Kane to the effectiveness of his man oeuvre, the egg had once more rolled over and was lying on its side.

Father now pulled the bottles containing the poultry monstrosities from the shelf from where they had been stored and started to exhibit them to his visitor, enthralled by the showman's ardour and at the same time greatly alarmed by the failure of his first attempt. He displayed the most amazing of his possessions and said, "How would you like to have seven legs and two heads like this fellow?" His face was animated with a smile. He attempted to slap Joe Kane on the shoulder like he had seen men do at Ben Head's bar when he was a young farmhand travelling into town on Saturday nights. He reached over the counter but failed. The sight of the body made his guest a little queasy got up to leave after noticing the horribly malformed bird floating in the booze in the bottle. Father guided the boy back to his seat as he emerged from behind the counter by the arm.

He experienced a brief fit of rage and had to momentarily turn his head away while forcing a grin. He then repositioned the bottles on the shelf. As an act of kindness, he fairly forced Joe Kane to purchase another cigar and a new cup of coffee at his expense. He then claimed to be going to perform a new trick as he took a pan and filled it with vinegar from a jug that was sitting underneath the counter. He said, "I'll warm this egg in this vinegar pan." "Then, without cracking the shell, I'll insert it through the neck of a bottle.The egg will take on its usual shape and the shell will harden once it is inside the bottle. I will then hand you the bottle containing the egg. It is portable and easy to carry everywhere. You'll be asked how you managed to get the egg into the bottle. Do not inform them. Make them wonder. That is how you may enjoy this trick.

Father gave his visitor a wink and a smile. Joe Kane concluded that the individual who approached him was harmless and only marginally deranged. He sipped the coffee that had been offered to him before starting to read his paper once more. Father brought the heated egg on a spoon to the counter after heating it in vinegar, then went into a rear room to get an empty bottle. He was upset that his visitor did not see him as he started to perform his trick, but he still went about his business pleasantly. He fought for a long time to get the egg to fit through the bottle's neck. He reheated the egg by placing the vinegar pan back on the flame, then picked up it and got finger burns.The egg's shell had softened a little after a second soak in the hot vinegar, but not enough for his needs. He toiled endlessly, and a spirit of ferocious determination possessed him. When he believed the trick was finally about to be completed, the delayed train arrived at the station, and Joe Kane began to walk casually out the door. Father made one final, valiant attempt to subdue the egg and get it to perform the action that would solidify his reputation as someone who knew how to amuse visitors to his restaurant.The egg worried him. He made an effort to treat it roughly. He cursed, making his forehead sweat more noticeable. Under his grip, the egg cracked. Joe Kane, who had been standing at the entryway, turned and smiled as the contents spurted all over his clothing.

My father's howl of rage sprang from his throat. He shouted a series of illegible words while dancing. He reached for another egg from the counter's basket and hurled it, almost missing the young man's head as he ducked through the door and fled.

Father carried an egg upstairs to my mother and me. I have no idea what he had in mind. I suppose he had some intention of destroying it and all eggs, and that he wanted my mother and I to watch him start. Nevertheless, something occurred to him when he was in mother's presence. As I've already mentioned, he lowered on his knees by the bed and delicately set the egg on the table. Later, he made the decision to close the restaurant for the evening and head upstairs to go to bed. He then extinguished the light and, after much mumbling, both he and his mother fell asleep. I guess I did as well, but my sleep was interrupted.

I got out of bed at the crack of dawn and spent a long time staring at the egg on the table. I questioned the necessity of eggs and the origin of the hen that later laid another egg. The query made my blood boil. I suppose it has remained there since I am my father's son. In any case, I still don't think the issue has been resolved. And that, in my opinion, is just more proof of the egg's unquestionable victory, at least in my family's eyes.

About the Creator

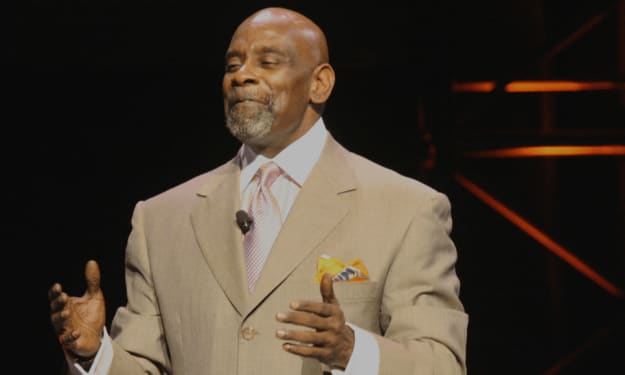

Bikash Poolingam

"Don't bend; don't water it down; don't try to make it logical; don't edit your own soul according to the fashion. Rather, follow your most intense obsessions mercilessly."

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.