Ancestry

A significantly cropped version of this story (they said 500 words max) was submitted to Scotland's Stories Now as part of the Year of Stories 2022 under the title On This Day and read during the Edinburgh Book Festival in August 2022. This is the full version.

On this day last year, I wrote the message and forced myself to click Send (with my heart trying to jump out through the throat, my body refusing to breathe).

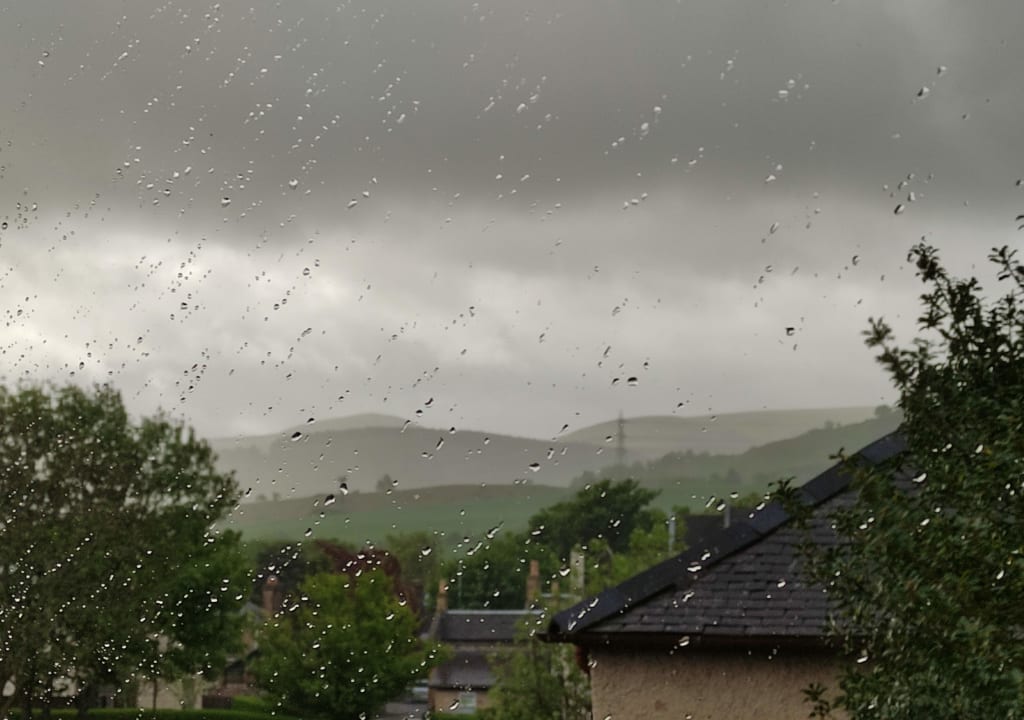

Then I stood up, went to the kitchen and put the kettle on. I looked through the window at the hills shrouded in the morning mist. There was no trace of yesterday’s snow.

'I am alive', I told myself, not entirely believing my own words. The voice sounded foreign. My body was a hollow shell I no longer knew.

There was this empty kitchen and the hills outside. There was this clumsy body with its sore back and the terrified mind inside like a panicked ferret. The person looking through the window, waiting for the kettle to boil, felt like someone I haven’t met before. This moment in time felt too tiny to contain all it had to hold. How many paths had to converge to conceive this here and now? Surely, it must have begun long before my birth. But the furthest my memory could go was to my great-great-grandmother.

The only thing known about her is that she gave birth to almost twenty children. The first-born daughter died in infancy but the second and the third child survived. A boy and a girl in the long procession of lost pregnancies and nameless infants put into puny graves.

The girl was great-grandmother Tekla, a humble farm hand with no home she could call her own. Although never married, she managed to raise a boy and a girl, her second and third child. The first-born daughter died in infancy. Tekla had never disclosed the name of their father, not even to her children.

The third child, my lovely Granny, had never married either. With her education finished after eight years of the Polish primary school, Granny survived two world wars and raised two children: my mother and her younger brother. Her second and third. The first-born daughter, fathered by a different man, died aged just two weeks. A tragedy? Perhaps. But also a relief for the single mother with no home to go to after losing her first job. The employer, a stately notary, could not stand the disgrace of the teenage maid making him a father. Surely his wife was not thrilled either.

My mother came into being several years later, at a large farm in Germany. It was a bleak winter night and Granny was able to get a few hours of rest before the dawn came and she had to work again. The year was 1943 and forced labourers working the fields in the middle of nowhere had to start early. ‘It wasn’t that bad’, I remember her saying. ‘You can always find something to eat on a farm. We didn’t go hungry.’

Granny (a smart one) had never let it slip how well she spoke German. While on the farm, she could only understand a few simple commands. On Sundays though, with the bright yellow ‘P’ on her sleeve meticulously covered with a large scarf, she would go to the nearby town with a basket full of food. She would meet a man there, transfer the food to his bag while the information was being transferred at the same time. The forest people, the undernourished Polish resistance troops, were always hungry. My mother’s father, grandfather Michał whom I have never met, was one of them.

She would return to the farm with an empty basket and her sleeve covered on the train where the Polish slaves were not allowed to sit next to the Übermenschen. Other passengers tried to chat her up sometimes. She always replied politely, with a demure smile and a perfect accent.

My mother’s name was Hänchen, the German version of Janina that in Polish is the female version of Jan (the name of Granny’s brother). As soon as there was no doubt that the war was finished, Granny went back to Poland with three-year-old Hänchen and a seven-month-old swelling in her belly but no man she could call her own. The father of her children had been elated at the news of the German capitulation. ‘Now we will show them. This will be our last fight’, he said.

He was right. The forest people were surrounded and none survived the ambush on that day, a few weeks after the capitulation.

Granny lived though and her daughter too, although she had to stop being Hänchen now that they could become Polish again. A confused (or maybe just tired) official translated the name on the birth certificate as Joanna and changed number 18 in the birthdate to 16. Little Hänchen-Joanna still didn't speak Polish but was not allowed to speak German anymore. Knowing the attitudes of her freshly freed compatriots, Granny kept saving both their lives by smacking the girl in the head every time she opened her mouth.

Granny’s belly survived too, despite the mighty kick from a Soviet soldier guarding the refugee camp. Uncle Wiesiek had to leave the womb two months early and never came to terms with the fact. He went through all the fifty years of his life kicking, screaming and stealing other people’s cars with his mates from prison (alcohol and cigarettes were his more faithful companions, they never left him in times of need).

My mother, whatever her name and date of birth, was the good kid. Her clothes always meticulously ironed, her hair arranged just so, she worked incessantly: helping at home, cooking and cleaning, taking the beatings from her premature brother in silence. In spite of these efforts, children at school did not like her. They kept mocking the ‘janitor’s daughter’ and pushing her around. Nobody likes the janitor able to make children toe the line, shouting at those who forgot to wipe their boots before stepping on the freshly mopped floor. And nobody liked her daughter.

It took many years and many men (some of them married, some not) before Hänchen-Joanna finally settled for my father, no longer married and 18 years her senior, with two almost adult children in tow.

This is where I step into the picture. My mother’s first-born daughter, very much alive despite all the diseases that plagued my early years. Her narrow-eyed gaze, disgusted with such stubborn aliveness, would often stop me in my tracks. I would freeze under its weight.

How do you deal with a child that refuses to die? You might give it to someone who knows more about life and death, who has already dealt with both a lot. This is how, at the age of three, I met my Granny.

She taught me how to read and write, crochet and mend my clothes. She told me the names of all the plants and creatures in her boundless garden, and would repeat the times table with me until I learned it by heart. She was the one to hug me when I cried, the one I ran to when my bruised knees or a broken heart needed mending. She has almost seen me through my teenage years. I was fourteen when, all of a sudden, her heart could not be mended anymore.

My mother, whatever her name and date of birth, has also taught me a lot.

That my needs were called whims.

That there was only one right way to feel and think and I kept getting it wrong.

That I did not feel what I felt and did not think what I thought. And when I said I was in pain it meant that I was lying.

How was I supposed to know myself after that?

She taught me that I did not matter. Whatever I had should have been hers, love had to be earned by being useful and I had to stay with her, never allowed a life of my own.

All these beliefs had to be burned out of my mind in the roaring fire that my adult life has become.

I’m still sweeping the ashes.

This is why, on this day last year, I typed: ‘Do not try to contact me again’. Then I blocked a few numbers in my phone, went to the kitchen and put the kettle on.

‘I am alive’, I thought.

In this new country, my new home, I thought about the childhood spent in a place so different, and yet so similar in many surprising ways. The Polish blackbird’s song that used to lull me to sleep after long summer days, the smell of rain in the air… They are the same in Scotland.

See, my tiny firstborn grandmothers, my little aunties who never got the chance to outgrow your infancy? I made it. To you, who have never been welcome, I am offering two countries I call home. Feel free to make yourselves comfortable. What tastes, sights, sensations do you crave in your silent dusty graves? I will offer them to you, just give whatever sign you like. What would you like to experience, my lovely nameless girls who came before me?

I’ll do it. And maybe, just maybe, this path will lead me to the place of knowing who I really am.

I can do it. I am still alive.

About the Creator

Katarzyna Popiel

A translator, a writer. Two languages to reconcile, two countries called home.

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insights

Compelling and original writing

Creative use of language & vocab

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

Excellent storytelling

Original narrative & well developed characters

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

Masterful proofreading

Zero grammar & spelling mistakes

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Comments (1)

Riveting, real, impressive writing that curled around my throat and left me breathless. I feel it as I read it, and and I read it, I know myself through your words in ways my brain is still struggling to gnaw through. That this story isn't a Top Story is an upset, but that's on Vocal. There's little Vocal could offer that is deserving of your fine storytelling. I'm awed. "Granny kept saving both their lives by smacking the girl in the head every time she opened her mouth." Tears. So entirely relatable. My grandmother kept a yard stick for just such occasions. And these words: "My mother, whatever her name and date of birth, has also taught me a lot. That my needs were called whims. That there was only one right way to feel and think and I kept getting it wrong. That I did not feel what I felt and did not think what I thought. And when I said I was in pain it meant that I was lying. How was I supposed to know myself after that? She taught me that I did not matter. Whatever I had should have been hers, love had to be earned by being useful and I had to stay with her, never allowed a life of my own. All these beliefs had to be burned out of my mind in the roaring fire that my adult life has become. I’m still sweeping the ashes." Oh my goodness. These words. You've picked up my life and set yourself inside it all, the torment, the anguish. You've painted my childhood with damning true brushstrokes. I'm a teary mess right now, but it is an honor to be seen. Your profile tells me you're a translator. You've certainly translated the world for me. BRAVA! 💛💛💛💛💛