My bedtime stories were filled with monsters.

As a child, I spent many summers in the Philippines, falling asleep to the sound of swaying palm branches and the rustle of thatched roofing in the evening breeze. But my favourite memories are of the tales my grandfather told me in the dying summer light. Fantastical tales of Philippine creatures, spirits, and monsters. He sat by my cot and told me of the aswang, women whose arms become wings as they detach from their torsos to search for victims, sucking out their guts using their long, tubular tongues. He described the tikbalang, a giant horse-headed man who makes people lose their way. And the mambubuno, a double-tailed mermaid who lures men away to live with her under the sea.

Gory? Yes. Terrifying. Also, yes. Appropriate for a five-year old? Probably not.

But I was riveted to the fantastical tales, and I craved the time with my grandfather, who told his stories with animated expressions, funny voices, and sweeping gestures. He had me giggling one minute and trembling with the covers pulled up to my ears the next. If you want all gruesome glory, I can still rattle off the names of dozens of Philippine demons, spirits, vampires, and epic heroes. His stories have stayed me me across the ocean, even though the decades after he passed away.

But the bedtime story that is most precious to me is the one where the mundane became monsters.

I always knew when my grandfather was about to tell the tale of the monkeys and the butterflies. He would take my hand, and his voice would be soft and grave. To me, monkeys were funny, and butterflies were whimsical - but this story was always serious.

It goes something like this:

Deep in the forest, there lived many monkeys and many butterflies. For a time, they lived side by side but separately. The monkeys ate the fruit, and the butterflies drank from the flowers. But one day, the monkeys decided that the forest was only theirs, and that the butterflies had no place among them. So the monkeys took up sticks as clubs and fell upon the butterflies. They smashed the butterflies with their sticks until only one remained. The last butterfly escaped to the very top of the trees. She looked down at the broken wings of gold, black, red, orange, and blue on the forest floor and wondered, “What have we ever done to deserve this? All we have done is drink the nectar of the flowers, and if we didn’t, the flowers would not produce seeds, and the seeds would not make trees, and the trees would not bear fruit for the monkeys.” The butterfly grew mad with rage and began to flit from monkey to monkey, resting on each monkey’s head for just long enough that the monkeys began to strike one another. She moved from monkey to monkey, baiting them into accidentally killing each other until there was only one monkey left. The last monkey was tired, and as he panted, the butterfly hovered before him and said, “You are the last monkey, and I am the last butterfly. Should we not talk? Put down your stick.” So the monkey listened as the butterfly explained that if there were no butterflies, the monkeys would starve. Then the monkey grew sad and remorseful, and they agreed to peace between them. Since then, no monkey has ever had a quarrel with a butterfly.

When I was young, this story was about working together and appreciating others. When I was a teenager and young adult struggling to make my way in the world, this story reminded me of my value in society, even if others seemed determined to push me out (yes, I believed I was the butterfly). When I started telling this story to my own children, I saw myself in the monkeys and recognized my own complicity in the endless cycle of discrimination. In the light of recent anti-Asian sentiment, this story has become even more important to me as a simple allegory of racism and society. The moral of this ancient tale is that we all have the capacity to become monsters if we won't recognize the good in others.

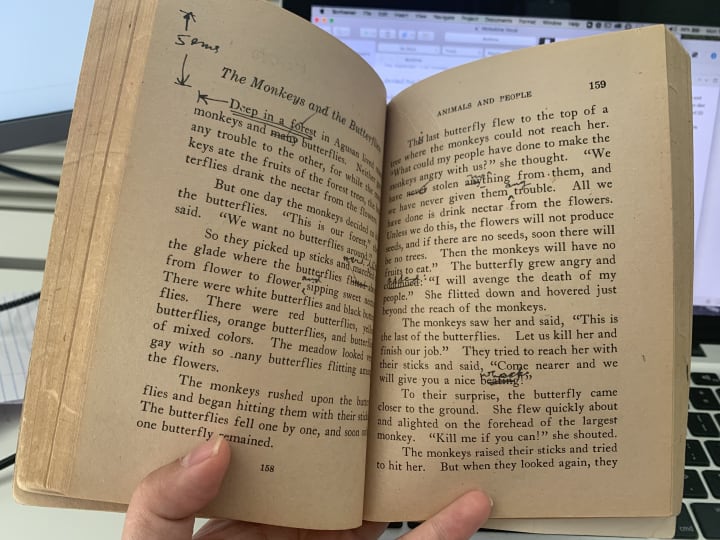

This story, along with all the other culturally rich tales he shared, is a gift from my grandfather. After all, curating the tales of Philippine lower mythology was his life’s work. My grandfather, Maximo Ramos, was known as the “dean of lower mythology” in the Philippines, and he researched and wrote extensively about Filipino myths and superstitions. Recently, my mother gifted me some of his original books - complete with author and publisher notes. They are among my greatest treasures. I’ve savoured each hand-written note in the margins, searching for hints of my grandfather in each loop of his distinctive script.

I may not share all of the stories of ghouls and demons with my children right now because my six-year old may never sleep again. But I do hope to introduce them to their grandfather and their ancestral cultural by gradually sharing all of these stories with them.

I am grateful that my grandfather lives on through his stories.

About the Creator

Linda M

Incorrigible daydreamer.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.