I remember I had gone into the garage to get something. I can’t recall what that was now because I became distracted. There is a corner of the garage that is full of old junk. Things I’d meant to take to the tip months back. Things I meant to sell or take to the local charity shop, just a block away. I’m not sure why, after sorting through everything, I stopped and let it all rest in place, these odds-and-ends of a life. Worn-down brooms and battered lampshades. Fragments of those things that unaccountably tend to survive the death of their patron—the boxes of things that seem to mean something but which are, in practical terms, wholly useless.

I incline towards dust, it seems. It was that hour of the day when the light illuminates the air, and you can see particles suspended above the ground, dancing—wondering where to land, perhaps. The smell of dust is a peculiar thing. I’m not sure I or anyone else for that matter would recognise it if it were distilled and turned into perfume: it’s not like the aroma of cut grass or the scent of wet dog, which I have seen bottled somewhere, once. There’s nothing defining or different about the smell of dust. It’s ubiquitous, bland and yet, fascinating. Like the squareness feeling of opening a box. Like the texture of old paper—the yellowing at the edges and the pattern of insect stains on the inside covers of old books.

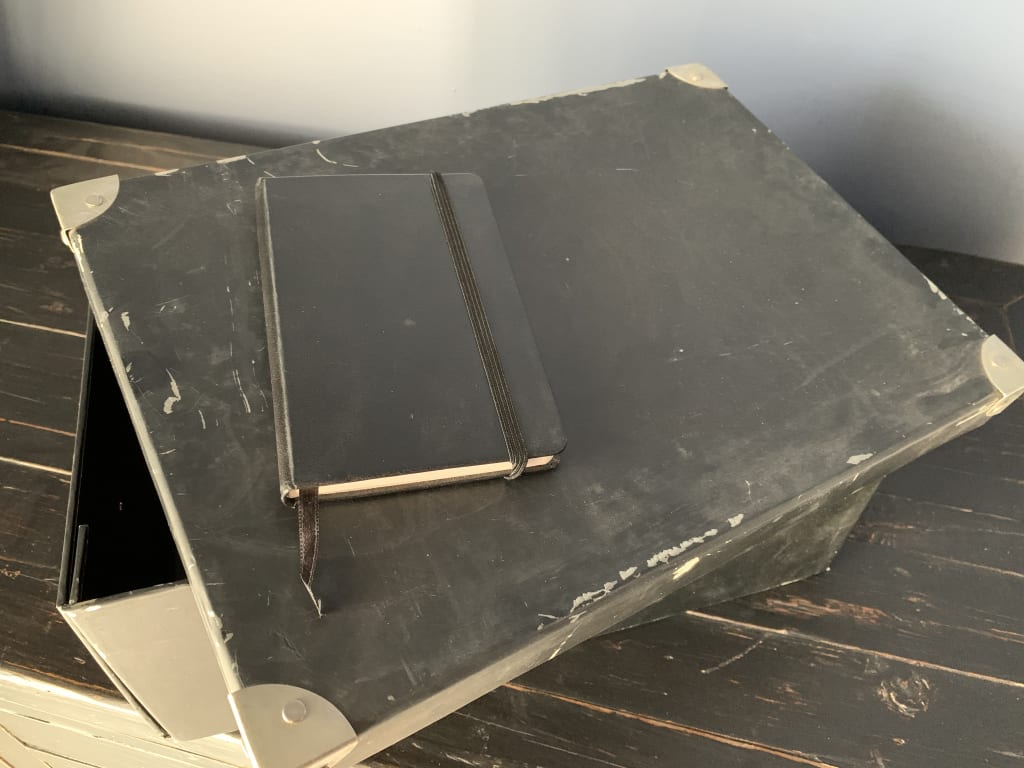

This inclination towards dust is probably why, after going into the garage for some practical but forgotten purpose, I found myself standing before a battered filing box labelled, “Mum’s things.”

The strangeness of a box is not something many people think about, really. But it’s an unnatural, artificial shape, and when it is crowned with a lid, that oddness becomes mysterious. Like a foreign language, of sorts: recognisable for what it is, but strange, nonetheless, because a box of things with a lid becomes an archive, in its way—an archive, written in another language.

In this instance, that language was Pitman’s shorthand. I had lifted the lid and picked up the little black notebook that lay on top of the pile of papers and photographs. I found myself looking at that inscrutable scrawl, written in my mother’s uneven hand—astounding that she remembered her shorthand (learned in adolescence) until the very end. She would scribble shopping lists and notes to herself in lines and dots, in hooks and waving tremulous symbols, in a code that somehow condensed ordinary language—a bit like stars before they burst.

By the dates that appeared throughout, I could see that this notebook was very old—almost as old as I am now. I would have been five, I think, when my mother began using it. Strange that she kept it. But then again, she was inclined to hoarding—the necessary precursor to my love of dust, I guess. I remember seeing a small black notebook like this one, sitting underneath a glass jar with receipts and other bits of paper shoved into it. I had already inspected that jar by the time this little black parcel of thingness arrived on the scene and knew that there was nothing of interest to a child of my age. No sweets, no coins, nothing remotely interesting by way of secrets. I can even remember seeing the little black notebook on the kitchen table, closed or sometimes sitting open because my mother had just left her seat to answer the door or for some other reason.

There was nothing hidden in it. Nothing that was to be kept from me. No terrors or private dialogues, and even if there had been, I could not understand it.

There is so much to do when you have to manage the affairs of someone who has passed. I must have gathered up her paperwork and placed it in this box, but I can’t remember doing so. I would have paused to look at the book otherwise. It’s hard to know for certain because it was so long ago. My mother has been dead for five years now. I’m not seeking sympathy by saying that. I am well past grieving for her, and, besides, she was ninety when she died. In fact, I am now about the age she was when she used this notebook. I realised this as I looked at it when I found it in the garage. Perhaps the affinity cracked the code for me because I began to understand bits and pieces of it. Here and there, words appeared where she had forgotten her shorthand. I recognised things by their form more than their meaning—a shopping list, the dates of birth of distant family members, long dead. At least, I assume them to be dead. I was the youngest child of the youngest child—and my mother was in her mid-forties when she gave birth to me and my twin sister, Shell (the likelihood of having twins apparently increases when a woman gets older).

Anyway, my cousins were only five or ten years younger than my mother. I had never met them, probably because we had nothing in common and, besides, back then, it was a shameful thing to bring a child into the world outside marriage, never mind two at once.

I suppose all this formed in the back of my mind as I looked through my mother’s notebook. Or perhaps these matters only come to me now. It doesn’t matter.

After a series of random entries, I came across a page with a name, a date, the abbreviation “dec.”—deceased? And “12m” written after it. Perhaps that’s what made me think of dead relatives just now.

On the pages that followed, the figure of $20,000 was written at the top and repeated on several pages. Numerous figures were added and tallied on these pages. One figure that, like the amount of $20,000, was a constant—though it varied from time to time by a few digits.

Then came a series of pages with addresses written across the top and the same arithmetic written below. Beneath each address, a large figure. Though there was one figure of $17,000, crossed through by the word “dump,” the figure recorded beneath each address was usually upward of $20,000 ($24,000, say, and even as high as $27,000).

After the address and what I assumed was its price, there was the figure of $20,000, followed by the negative figure, which was sometimes $4,000-odd, sometimes a little over $5,000. The resulting sum, usually thirteen or fourteen thousand by the time other expenses were deducted, was subtracted from the larger figure given beneath the address. For example:

24,000

- 14,753

= 5,247

It’s amazing how a revelation, even one so long after the fact, can affect you. As I read those financial sketches, I recalled mum dragging Shell and me around the neighbourhood and further afield and us walking into empty houses—some furnished, some not. There were men in suits, smiling because we were twins and people smile harder at pairs for some reason. They were smiling at mum too and talking up the garden and the kitchen facilities—hot water was a boon, apparently.

We had no hot water in the kitchen at home or over the basin in the bathroom. I remembered that, but it never bothered me as a child, perhaps because we did have it in the shower and over the bath. Still, the strangeness of a man in a suit walking up to the faucet, turning it on, and announcing, “hot water!” made the experience memorable. (Shell and I even invented a game where one would be indoors and the other would go outside and knock and, upon being allowed inside, race to the kitchen sink and announce, “hot water!”)

I think it was sometime later, in the late seventies or early eighties, that hot water was plumbed to the sink in the kitchen. Before then, mum would boil the kettle. It’s probably why I never learned to do the dishes properly as a kid. I always thought it was down to clumsiness. But it wasn’t because I was clumsy. I was too small to boil a kettle and pour it into the sink safely.

By the time water was plumbed into the kitchen, I was well on the way to hating my mother and probably never offered to do the dishes or anything else about the house, and she, from feelings of guilt, perhaps, never asked.

Before I learned to hate her, there was this little black notebook and the aspirations it recorded and the longing that was lost and which got turned into the anger and the frustration that she sometimes directed at us. We didn’t have a car, so we went everywhere by bus or train. Mostly, we walked. I remember Shell having a tantrum, lying on her back, fifty yards from home. She was prone to fits of anger, Shell was—you know, racing off and stuff, but this time she reckoned she couldn’t go any further, and so she collapsed. More often, she’d run.

I remember it still. Mum yelling. Shell running off. Then I’m hoisted up on mum’s hip, and we’re running too. I can feel the uneven texture of her cardigan against my cheek and, now and then, her skin, which looked leathery and wrinkled but felt soft.

We didn’t have a car, but I remember the smell of exhaust fumes after Shell’s accident. Later, when the notebook had been put away, and the jar in the kitchen was emptied and stowed away in the cupboard, I remember the social worker coming, and the priest too—he came first. And I remember finding a little beige booklet that described the allowance mum received from the government as a “deserted wives pension.” That’s when I learned that she would get less money without Shell.

My mother was the sort to talk and talk. And she talked through her grief, not thinking of me. Not thinking how I might feel about Shell being dead and me being alone. So, she talked to everyone who came to see us in sympathy or out of pity. I remember seeing a pair of shoes, and the thickness of the leather, their dull matt colour. There was the sound of feet scuffing the linoleum and the kitchen dresser wobbling slightly as the woman and my mother left the living room—their steps a signal to me to move away from my listening post.

It is the smallness of the lives lived, and the largeness of remembering that gets put in a box when you pack it away out of sight. I had thought the woman came out of concern. She listened to mum tell her this and other stuff—how she’d tried but couldn’t get a loan for what she called the shortfall. I remember the woman’s legs: knee-length skirt and sensible, though elevated shoes. Working shoes. Shoes for women who worked. Mum called her the social worker, but she could have been what was called a field officer. In my twenties, I’d worked in the very department that used to pay for my upkeep as a child. Field officers used to check up on single parents like my mother. Bed sniffers, they were called in the department. They’d go through the house, into bedrooms and closets, looking for signs of there being a man there. But there were no men in our house. That’s why mum couldn’t get the loan when she inherited $20,000 out of the blue. A stroke of good fortune to anyone else. But it wasn’t for us. That’s why the woman said, “Spend it.” Mum would lose her pension otherwise. She had too much money, apparently, for government support and not enough to pay her debts and buy a house.

About the Creator

Victoria Reeve

Creative writer and academic, specialising in theories of narrative emotion and reader involvement.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.