GIVING BIRTH IN VICTORIAN TIMES

Marriage and pregnancy were considered a woman’s only proper occupation, and birth control information was forbidden in the nineteenth century

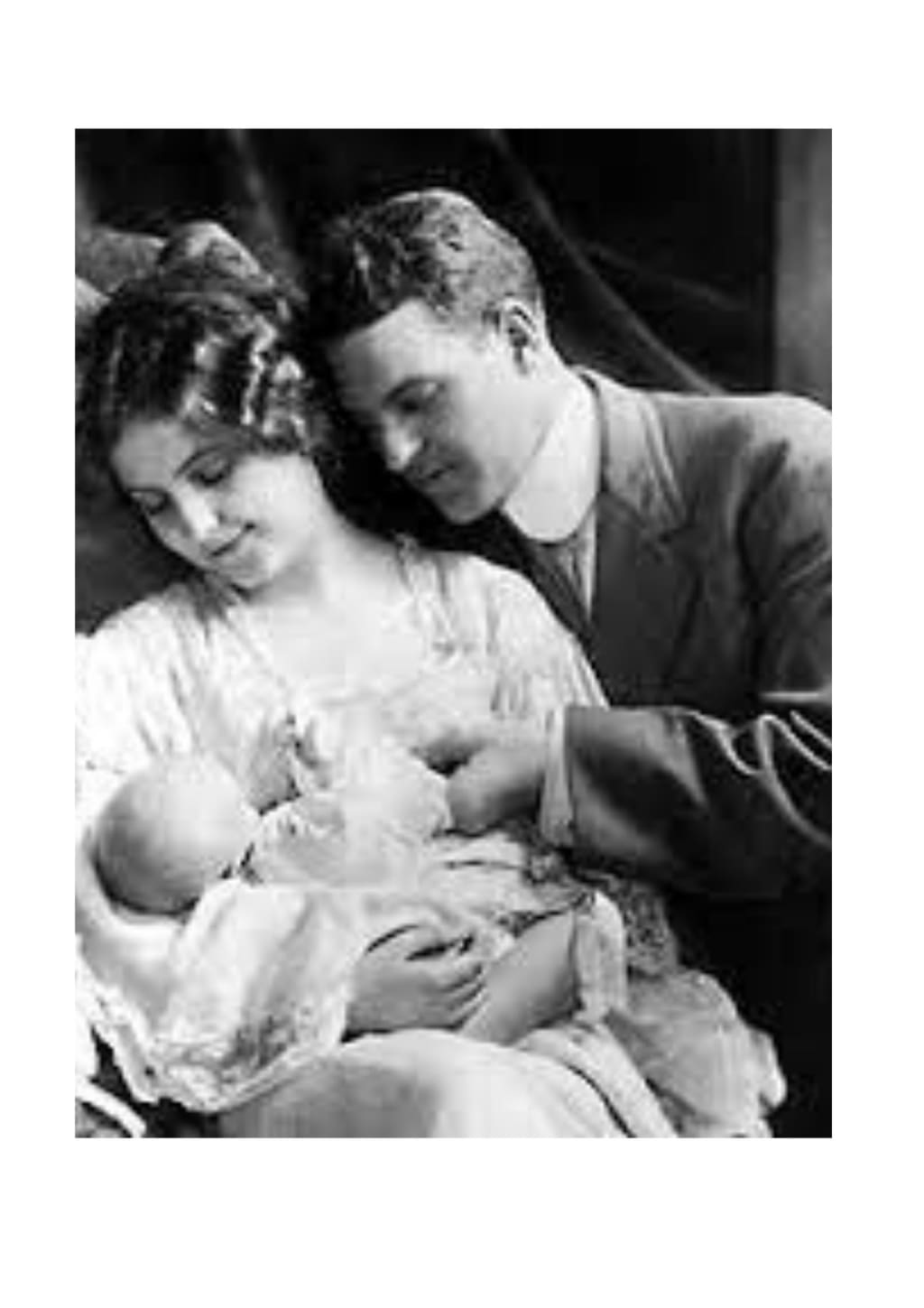

If you think pregnancy and giving birth are difficult in the 21st century, imagine being a Victorian pregnant woman–wondering if either your pregnancy or your baby’s birth would kill you or not.

When people married in the mid-nineteenth century, they assumed children would follow quickly and frequently. The usual sense was children just came, and there was nothing to be done about it. They encouraged women in those days to see motherhood as a duty.

Marriage and pregnancy were considered a woman’s only proper occupation, and birth control information was forbidden in the nineteenth century. The average working-class wife was pregnant or breastfeeding from her wedding day to menopause. Women who married in their early to mid-twenties could expect to bear children continuously into their early to middle forties. Families were large, with an average of six to eight children, but averages can be misleading. Families with many more children were common.

Far fewer children were born in the upper classes, showing some educated people knew how to avoid pregnancy. Premarital pregnancy was infrequent among the upper classes. This was usually because someone always chaperoned everywhere girls they went. A lot of working-class women became pregnant outside of marriage. But because of social disgrace and the lack of money to raise the child, many hid their pregnancy.

If a domestic servant became pregnant because of her employer, sometimes the family banished the girl from the house, but they often pressured the couple into marrying if her lover was working-class. Throughout the nineteenth century, a lot of newborn babies were strangled or smothered. If they found the mother, she would be charged with murder and tried by an all-male jury.

In those days, childbirth was painful and dangerous. The only pain relief available was opium, usually sold as a sleeping drug known as laudanum, but was rarely used. Most babies were born at home, with the help of family and friends. Some women practised as midwives, although they had no formal training. Doctors were asked only to attend if the births were protracted, and it was feared the mother might die.

The problem with doctor’s interventions brought risks. There were instruments for childbirth, but no anaesthetics or understanding of antisepsis, which meant that the danger of infection from medical intervention was grave. This meant doctors were sources of infection, transmitting infection from their previous patients. Hospitals were places of last resort, used only by the very poor. The death rates in hospitals were extremely high.

The chief dangers in childbirth were prolonged birth, extreme bleeding, and infection. Prolonged deliveries often followed when labour began with infants in the breech or transverse a position. They would attempt to turn the babies but were rarely successful. Another common problem was a narrow or deformed pelvis caused by childhood rickets, a disease especially widespread in poorer women.

In life-threatening cases, where it became clear after days in labour, a doctor would usually attempt to use instruments to get the child out or crush the child and remove it. At this stage, the baby would often already be dead, and the mother would also die, either from shock or from infection. Excessive bleeding was another common problem, and there was almost nothing a midwife or doctor could do to stop a post-birth haemorrhage, and many women bled to death. Infection was another menace in childbirth. Women are vulnerable to infection during and immediately after delivery, and fever was common and much-feared in the nineteenth century.

Women approached each birth with trepidation, and many women routinely prepared themselves for death. Using pain relief increased towards the end of the century when Queen Victoria famously pioneered chloroform and helped to popularise the practice, but many doctors still opposed its use.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, there was a growing sense that women’s lives might be saved if they could deliver babies under medical supervision in hospitals. Using anaesthetic became popular — however, it received a religious backlash. Many clergy members argued ‘that this human intervention in the miracle of birth was a sin against the will of God. If God had wished labour to be painless, he would have created it so.’

Possibly the most ludicrous aspect of being a pregnant woman in the Victorian period was pre-natal advice. It is said that pregnant women during the 1900s were told there was a link between pre-natal nourishment the temperament of the baby: one strange one being they were told to avoid sour foods such as pickles, because these types of foods might give the baby a ‘sour disposition’!

About the Creator

Paul Asling

I share a special love for London, both new and old. I began writing fiction at 40, with most of my books and stories set in London.

MY WRITING WILL MAKE YOU LAUGH, CRY, AND HAVE YOU GRIPPED THROUGHOUT.

paulaslingauthor.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.