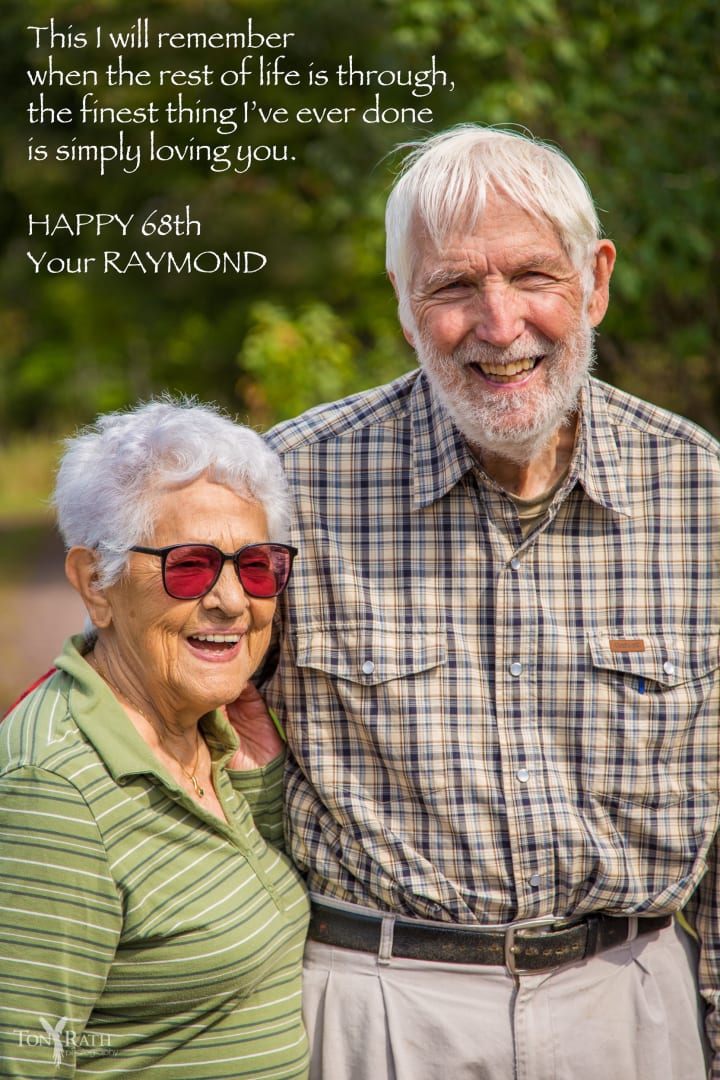

At 93, Mom didn’t rage against the dying of the light. Her heart - big enough to raise 6 children; brave enough to sail the seas for 7 years; bold enough to live off the land in Northern Minnesota for 20 years; and robust enough to love the same man for 73 winters - weakened, surrendered and stopped.

Death is such a personal event, for the one who died and those loved still living. But the feeling of loss is also universal. I wonder why people are so uncomfortable around loss? Friends whisper condolences and cliches like “Sorry for your loss” and “My thoughts and prayers are with you”, meant to ensure we don’t say the wrong thing.

I am embarrassed by the grief I feel and the attention it draws because it is not special. To write something about Mom seems pointless and a little egoistic — the pain is mine. I feel like the loss of my mother, however unhappy or painful, does not give me the license to intrude on others, most of them strangers who know nothing of Mom or me - is there not enough pain and suffering in the world already? But a good friend once told me to tell my stories, create my photos and let the viewer decide; and as a photojournalist I used my camera to manage the pain. These photos, often created through tear-blurred eyes, are the result.

In retrospect, I actually spent very little time with Mom. After my first 18 years at home, I left never to return except for brief visits.

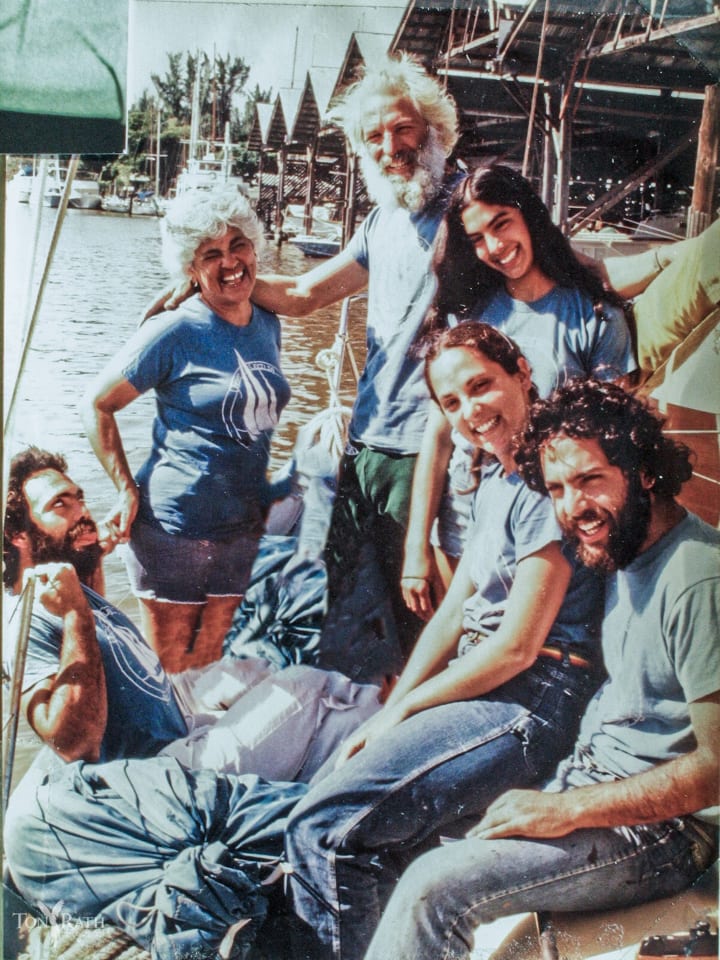

I was lucky enough to spend part of 7 years with her on a sail boat cruising across the Atlantic Ocean twice and through the North, Mediterranean and Caribbean Seas. I took cooking instructions from her as she lay seasick in her bunk. She was terrified of ocean crossings - she never did learn to swim.

I tried to make annual visits to their farm during the fall deer hunting season in Northern Minnesota when I would help fill her freezer with venison. I can still see her smile through the kitchen window as I opened the porch door; still smell the aroma of fresh chili on the stove; still hear her lovingly admonish me to remove snow covered pants and boots and “close the door!”.

Mom was a cribbage fanatic even though I sometimes had to help her count her points - and never take any that she missed! She was a cleanliness fanatic; visitors never found mildew in the bathroom or cobwebs in the corners or water spots on the windows. Her hair was always brushed, earrings usually framed her smile, her clothes immaculately brushed for lint. She was often described as classy even at 93. Mom wore her feelings on her sleeve, people knew when she approved or disapproved. And cook - well everyone loves their mother’s cooking. But my high school buddies would often invite themselves over after football practice for a dinner of Mrs. Rath’s tortillas and refried beans.

Yet, with all the wonderful memories, it was the last three weeks of her life that I will always cherish most, for just like she brought me from darkness to light through birth, I helped her from twilight back to darkness with her death.

In the midst of planning all the thrilling expeditions that a photojournalist living in Belize gets to do, I received a mid afternoon phone call from Croixdale, the assisted living apartment complex where Mom and Dad reside in Minnesota. The staff had a problem. Could I come immediately. Mom was scared. She was too weak to properly handle Dad’s increasingly erratic behavior brought on by early onset dementia. She needed help.

The staff at Croixdale interpreted this call for help as Mom fearing for her safety and by law they had to separate the two. For the first time in 73 years, Mom and Dad were forcibly kept apart, moved into different apartments. They were not taking it well.

For the last five years, ever since Mom began to have heart problems, Dad rarely left her side. Despite his early onset dementia, he used his engineering background to managed her complicated medication regimes through checkmarking printed spreadsheets he made; took and recorded her blood pressure twice a day; tracked medical appointments; accompanied her to the doctor checkups; always had an arm or hand ready when she moved. When she needed a pacemaker, he wouldn’t leave her side in the hospital unless one of the children promised to stay with her, then only to shower and eat.

Due to Mom’s worsening condition, they were forced to sell their beloved farm. After 50 years of developing a 1000 acres tract of pristine Minnesota forest and wild prairie grass habitat for wildlife, they donated 640 acres to the State of Minnesota to create the William M Rath Wildlife Refuge in honor of my grandfather. They sold the remaining acreage, including their home of 20 years, to a neighbor.

Dad stopped hiking, snowshoeing, cross country skiing and hunting. He stopped gardening (Dad was one of the first Master Gardeners in the State of Minnesota), stopped exercising, stopped doing everything he loved to take care of Mom, the woman he loved.

When I arrived at Croixdale at 1 am, 36 hours after that first phone call, I let myself into Mom and Dad’s apartment and found Dad alone in his bed, asleep. Pulling out the sleeping pad and bag I normally take on expedition to Belize’s hinterlands — which I had hastily thrown into a suitcase along with every long sleeve shirt I own — I crashed on the floor of the office next to his bedroom.

A bump and squeaky springs woke me at 6 am, and I tiptoed to Dad’s room and nudged open the door. He sat on the edge of his bed, head in hands, sobbing.

“Dad?”

I could not remember ever hearing my Dad cry. In the glow of a nightlight he slowly raised his head, turned and looked at me through teary eyes and moaned “Where is she? What’s happened?” Then without a pause said “How are things in Belize?”

A visit to Mom’s apartment was little different. After a long hug, through tears, she questioned what was happening. I later learned that the first night they were forced apart, the nurses on duty reported both of them wandering the halls at 2 am looking for each other (they had been placed on different floors).

After numerous consultations with nurses, doctors and administrators, we all agreed Mom and Dad could not be separated. We realized that Mom was actually asking for help in dealing with Dad, not fearing for her safety — stress at 93 can cause all kinds of confusion. The solution was more a question of oversight — they would have to move into an area of the Croixdale complex with closer supervision.

When I told them that they would be back together, you would think they had won the lottery. Mom found enough energy to go for a walk. Dad actually joked and laughed.

They were not happy about changing apartments. All of Dad’s routines, so important in dealing with his early onset dementia, would be disrupted. But they had no choice if they wanted to stay together. After the move, life was good and we could all get on with our lives. Or so I thought.

Life changes fast. One evening you kiss your Mother good night, she hugs you close and long, says “Thank you”, pulls you down for another kiss, gazes into your eyes and says “Love you”. And you go to bed feeling all is as it should be. The next morning you go to their room and all has changed. It is a moment that stays with you forever — something intangible, a sense, a look, an aura — when you know for sure that something is wrong.

Congestive heart failure occurs when the heart is unable to pump sufficiently to maintain blood flow to meet the body’s needs. While usually a long term condition, overnight it seemed Mom couldn’t talk, only whisper one or two syllables at a time between weak breaths. This frustrated her greatly as she loved to chat. She would nod off even while filing her nails and become confused about dates, people, and mealtimes.

Her feet and calves would swell like water balloons during the day — her heart was too weak to maintain water balance in the body. Compression socks did little to help. In the evenings I would take the socks off, and rub her feet with coconut cream. Her head would tilt back and a smile would appear as I rubbed first her heals and toes, then ankles and calves. She looked like she was in heaven already. I would have massaged her feet all day if she let me.

We seem to be programed to keep those we love alive and healthy — it is instinct. We need to protect them, we strive to alleviate any discomfort — we would do anything if only the pain would go away. In the end, we know we can’t make it go away or save them, but still we must try.

As Joyce Carol Oates wrote “Hopeful is our solace in the face of mortality”.

Getting old and feeble is really a lot of bodily fluid management and humiliation. Mom and Dad would spend hours in the bathroom cleaning her and rinsing soiled clothes. She told me she felt so bad that Ray had to see her like this, but she didn’t want any one else to, not even the nurses. Near the end, she didn’t complain when I helped her. There is no elegance or pride to be found with death approaching. The term classy lady is for a younger time.

The doctors at Croixdale said “we look at a patient and when we think the patient only has 6 months left to live, we’ll call hospice.” When they called hospice for Mom she only had days to live, that is how quickly she deteriorated.

Huge oxygen tanks appeared in the corners of the bedroom and living room; plastic tubes hissing with oxygen snaked around the apartment; a wheelchair replaced her walker; and a morphine/Ativan cocktail relaxed her and helped with her labored breathing. The doctors stopped all other medication. She stopped eating.

Dad sat and watched all the activity, but I am sure his brain would not register what was happening. Denying reality is sometimes a survival tactic. I am sure he could not imagine life without his wife of 73 years. They lived by routine and he did his best to keep by it. The afternoons were for naps, and to him - despite the strained breathing - Mom was peacefully dozing in her chair.

By late afternoon, all but Dad could see that Mom would make a final journey from chair to bed. While she slept, I gently lifted her in my arms and carried her to the bedroom. Nurses helped to change her wet undergarments and dress her in her favorite soft nightgown, then adjusted her to be as comfortable as possible in her bed — all without waking her. I put lip balm around her nose where the oxygen tubes were chaffing, then used a small sponge to drop moisture in her mouth.

She woke only one more time. Three nurses were trying to adjust her body position to relieve her labored breathing when her eyes squinted opened. Her eyes rotated from nurse to nurse with a lost, confused, scared expression. I squeezed between nurses, lightly took her hand, leaned in close to her ear and said “Hey Mom, it’s me.” She turned her head in slow motion, like a spiderlily flower opening, and looked at me. Her face relaxed with recognition and a hint of a smile nudged the oxygen tubes out of place on her nose. Her fingers moved as if they wanted to crawl up my wrist, then a slight pressure on my hand drew my forehead to hers till we touched.

For a moment she was Mom again. Though she could not speak, I knew she was saying all is OK, that she knew I would take care of Dad, that she loved me … then she was gone. The labored breathing returned, the skin on her face went slack, her eyelids closed. And right there, that moment of recognition, that smile, that touch, is worth more to me than all the adventures I’ve had; all the beautiful sights and wildlife I’ve seen; all the photographs I have ever made; and all the money I may make. With fake bravery, I readjusted the oxygen tubes, brushed a stray hair on her forehead into place with my fingers and kissed her forehead.

The early evening was hell. Mom’s breathing was so labored, each breath in was a moan, each exhale was a rasping snore. The skin on her face was sunken, ash-colored and wrinkled with what looked like pain. The nurses were coming every half hour now to adjust her, the morphine/Ativan cocktail increased in frequency and dosage, but still she seemed in distress. Dad was asleep in his bed next to her as if nothing was happening.

By this time Therese had flown in from Belize to help, and we were both 48 hours without sleep. Mom’s raspy labored breathing and moaning was affecting us, as a crying baby might a mother. By 10:30pm we were frantic. That is when Danica, a young nurses aid at Croixdale came on for the night shift. I don’t believe in angels, but if they exist, she is one. Danica entered the apartment, took one look at us, and with an understanding nod and smile, entered the bedroom. She was firm, professional, efficient. She changed Mom’s diapers and nightgown, pulled her toward the head of the bed, rolled her on her side, placed a pillow between her legs and propped one behind her back . She liquified the morphine/Ativan medication, and fed it to Mom with a baby spoon, moistened her lips and tongue with a sponge dipped in cool water, tucked her in, checked on Dad and turned out the light.

Mom’s breathing eased, the moans and rasps reduced to a whispered wheeze, she looked almost peaceful. Danica would return every half hour throughout the night, checking on Mom, Dad and us. Funny how I wasn’t sad, I was relieved. I sat just outside her bedroom door, counting her breaths. 16 per minute, then 15, then 14.

Recognizing the exact moment of death is tricky. Often Mom’s breathing stopped for 30 seconds, then would come another tortured breath. Her hands are warm. They say hearing is the last sense to go, so I tell her I am here. The room is lit by the glow of the closet light through a door that has been left ajar and silent except for the hiss of oxygen and the occasional snort from Dad sleeping soundly beside her. Mom’s face is slack and ashen, the strain gone. Her breathing stops and I wait for the next breath that doesn’t come. I check her pulse on her wrist which is now less warm, then her carotid artery on her neck. Nothing. I brush the hair off her forehead with my fingerstips and kiss her. It is 6:24 am, Feb 3rd, 2018 — 6 days before their 73rd wedding anniversary.

Purpose and love can mute grief. My only concern now is Dad. He wakes at 7am, and I can’t tell him. The funeral home will come for the body at 8:30am, time enough to dress him, feed him, and get him comfortable in his chair. As he dresses, he glances at Mom, but in the dim light — the shades are closed and he will not turn on the bedroom light to dress for fear of waking Mom — he does not notice she is gone.

Therese feeds him a grapefruit, two pieces of toast and a glass of milk while nurses and a doctor from hospice come to verify death. I help him into his lounge chair. Dad is smiling and laughing about something when I take his hand. He is still smiling when I say “Dad, Mom is gone, she died this morning”.

Disbelief. His hand goes to the top of his head. Then recognition of what I said. His face withers like a sped up time-lapse of a flower wilting. From somewhere comes a primal groan, almost an inhuman sound and a cry of “Oh God!” followed immediately by “She was my whole life!”. Who can know what 73 years loving the same person can do when it is taken away.

The days following are kind of a blur. We did not leave Dad alone. He went through the motions, but because of his short term memory loss, he was living the torture of learning Mom had died over and over…he kept forgetting.

During the following days his one request was to get him some where else, away from Croixdale. He needed the memory of Mom’s death to stick, and to do that he knew needed to stop living where they lived, change his routine, remove the signs of her being there. Every time he looked at the bedroom door he expected her to walk out — as Therese and I did. He needed to create a different present. We hope Belize will provide that different present.

Death leaves a heartache no one can heal, love leaves a memory no one can steal.

About the Creator

Tony Rath

Tony Rath is a writer photojournalist based along the shore of the Caribbean Sea in the picturesque town of Dangriga, Belize.

http://www.tonyrath.com

Facebook: BelizePhotography

Twitter: trphoto

Instagram: tonyrath

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.