A Small Black Notebook

The things worth remembering

I found it while packing up my father's house, on the coffee table in the den with the brown shag rug. A small black notebook with a soft cover. It looked like one Dad had when I was a boy. He said he used it to write things down he needed to remember. I went back to boxing up books and forgot all about it. My dad died two weeks ago.

He got Covid-19, although I can't imagine how. He never left the house except to walk to the mailbox. I delivered groceries to his screened-in porch. I wore a mask and waved at him through a window. Dad waited at least four hours before touching anything. Then he stripped off the packaging and sprayed containers that couldn't be removed with Lysol. When he finished, he washed his hands with surgical precision and scrubbed the counters. Dad, a former army captain, and a little OCD, enjoyed the drill.

I packed up his house over two days, taking my time. More than once, I started to call out to ask him what to do with something. But then I'd remember.

Before leaving the house, I surveyed my work. A dozen boxes (mostly books) and some furniture. The movers would imagine Dad an insignificant figure. He was not.

It's because of Dad I'm a writer. He gave me my first notebook and said: "It's the little things you forget that make up a life. You can write them here." He called me a natural storyteller with a writer's name: Quentin Conrad Jones. Quentin, from William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury, Dad's favorite book; Conrad, after Joseph Conrad, Dad's favorite author. Names that took some convincing with Mom.

It was just me and Dad for most of my childhood. A drunk driver killed my mother when I was four. Dad had returned home early that day. He had the flu and went straight to bed. Then the babysitter left, and it got dark outside. I crawled up on the kitchen counter and made a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. At some point I went to bed. The next day, Dad said Mom was gone. It's the only time I ever saw him cry.

I don't remember Dad ever staying sick in bed again. "If you are going through hell, keep going," he would say, quoting Winston Churchill. I think he blamed himself for Mom's death. They worked together at a factory. Dad on the shop floor; Mom keeping books in an office. I suppose he imagined if he hadn't come home early that day, he would have been with her at the bus stop and somehow protected her from the drunk driver who swerved his car onto the sidewalk, killing her instantly.

Mom quickly faded from my memory. I can't remember her touch or her smell or her voice. It's only from photos I can see her at all. She was a neat-looking woman with pale skin, light hair, gray eyes. In the photos, she looks faded as if early death was inevitable.

For my twelfth birthday, Dad bought me a typewriter. It was a beige Olivetti, sleek as a Ferrari. The boys in the neighborhood teased me mercilessly for boasting of getting an electric typewriter; for being a bookworm; for the classical music that blared from our house. I never cared for those boys, except for Kevin.

Kevin lived in the house on the corner with a tin roof. We used to lie on his bed in the attic, listening to rain beating like pebbles on a drum. We never did anything except hold hands. But I knew from an early age. And Dad knew too. We never talked about it. Not even when I married Paul (now ex), with Dad standing behind us as we exchanged our wedding vows.

In my last year at Penn State, Dad said a writer's life would be hard and I should find a job as a journalist or as a teacher and write at night. I worked construction and was a delivery driver for a while. I rose at 5 a.m. each day and wrote for two hours; a thousand words before breakfast. Dad said such discipline would pay off.

I sold my first novel at 22. Back then, there wasn't a genre called gay fiction, but publishers must have felt it was time. Otherwise, my book never would have sold. The story was as awful as the title, "One Perfect Love". An honest reviewer would have pronounced it: "Prissy and pent-up." In retrospect, I should have called it that. More copies would have sold.

I made $2,500 on that book. It was enough to convince me to keep writing and rent a cheap place to live in Jersey City. I got a bicycle messenger job in Manhattan and wrote "Master of Ceremonies". GQ called it "dark and funny" and called me "one to watch." Money from the book wasn't enough to quit my messenger job, but it gave me something to talk about in bars.

Soon after my second book came out, something miraculous happened. "Master of Ceremonies" won a $20,000 Cooper Literary prize. I didn't even apply for it, and it saved me. Jersey City may not be New York City, but it is expensive. I was nearly broke. Dad would have helped. He was frugal and had savings. But I wouldn't ask, and he wouldn't offer. Admitting I needed help, was like admitting we both had failed in some way.

At the award ceremony for the literary prize, I met a filmmaker. The next thing I knew, "Master of Ceremonies" was being made into a movie. For nine months, I lived rent-free in a bungalow in West Hollywood.

I paid to fly Dad out. I picked him up at the airport in a white convertible Mustang lent me by the studio. Dad looked smaller and shabbier than I remembered, and his skin had a waxy unhealthy glow. I joked that he could use some sun, and maybe some new clothes. He looked me straight in the eye and said: "Don't ever apologize for where you come from son."

It was the sharpest thing he ever said, and it stung. I bought him sunglasses and a sports coat, and brought him onto the set. He sat in a corner reading day after day, standing and shaking hands whenever I stopped by to introduce someone. When I walked him back inside the airport, he said it was the best week of his life. I laughed and said, "But you just sat in a corner and read the whole time."

"I got to see my son living his dream," he replied. "What more could a father want?" As he disappeared past security, I stood there and cried. I didn't care who saw.

The third book made me rich. It was the kind of thriller you buy in airports. I bought a place in L.A. and offered to buy Dad one too. But he said he couldn't leave my mother. Dad said now that I had money, I should write something more ambitious. To Dad this meant more literary. That was the second sharpest thing he ever said, and he only said it that once.

When Covid struck, I took an apartment in the center of my old town to be near Dad. He protested, but I needed a change. By then I was working on my ninth thriller. My plot lines had become as stale as the story I would tell about being named for Dad's literary favorites. I had a big name that I felt I didn't deserve. I decided to take a break from L.A.

The last morning I saw him was like any other. I put the groceries on the porch. We talked a few minutes through the window. I got in my car. Before driving off, I looked up to see him still standing there, his hand in the air. Why didn't I stay longer; say something meaningful? Why didn't I move in with him instead of getting my own place? How did I not see he was sick?

Later that day, Dad called an ambulance. The hospital wouldn't let me inside. A nurse said he had a tube in his throat and couldn't speak. Each night, the nurse on duty would hold the phone to his ear. I would say I loved him - something I never said in person. I said we'd see each other soon, trying to convince myself as much as him.

He died on October 22, the same day as my mother. Such an orderly soul, I can't help but think he planned it. When I went to the house to pack up, I found the groceries neatly stored, the bags folded and tucked away under the sink, and that little black notebook on the coffee table in the den. It wasn't like Dad to leave anything out, even with an ambulance on the way. Especially with an ambulance on the way.

I slowly packed the house. It smelled like Dad. Pledge furniture polish, a slight whiff of mothballs and a musty bookish scent. I met the movers on a Wednesday. Three masked hulking men. They finished in two hours. Two hours to clear out the contents of a man's life. One load to Good Will; another to the local dump. All that remained was a box of books and some photo albums for me to keep. One of the movers handed me the small black notebook I had left in the den. "Don't forget this," he said.

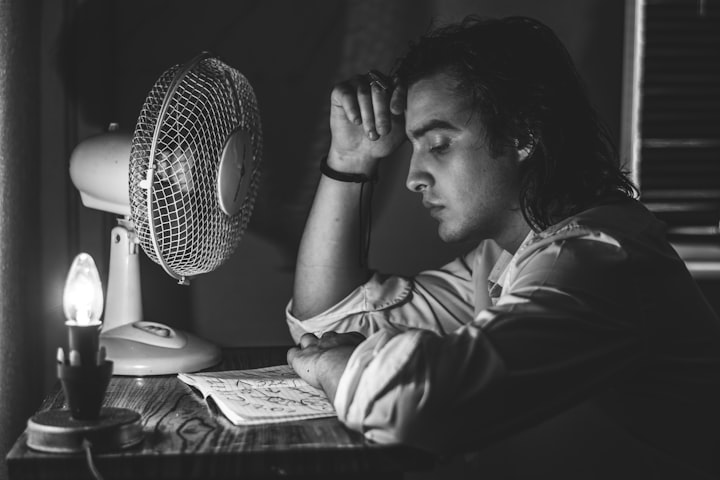

It wasn't until I got back to California that I finally examined the notebook. The cover was soft from decades of use. A frayed black strap held it closed. Inside, the silky-smooth pages smelled vaguely of vanilla. It was here I found in Dad's neat square script the story of our life after Mom died.

The story was beautiful and simply written. It was about stuff I had mostly forgotten, little moments that make up a life. The things Dad said he needed to remember.

Like the story of the first meal he made after Mom died. Dad took from the freezer what he thought were sausages. He baked them for an hour. They turned out to be bananas. The two of us laughed so hard we cried. He wrote about the first time I rode a bike. It seems I was a fast learner, but then with a big smile on my face, I lifted my hands off the handlebars, like I'd seen big kids do. I wrapped myself and the bike around a neighbor's mailbox.

Then there was the story of when he realized I was gay. "My son likes men," he wrote simply. "If there was anything I could do about it, I would. If only to spare him from the hatred of others. But I hope he knows that I love him just the same."

When they published Dad's story, they used a picture I took of him, reading on the movie set, on the back cover. His book inspired my next. It wasn't a thriller, and they didn't make a movie out of it. But it was about things worth writing down, and Dad would have been proud.

About the Creator

SG Buckley

Writer and editor in London.

I write about parenting, technology, sustainability, and other subjects, but it's fiction I love writing most.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.