Understanding Keystone Species

The arch which holds ecosystems together

Sisters, brothers, cousins, parents, grandparents, and more are just part of what makes up a family. There are also friends, friends-friends, acquaintances, and strangers. Each group has its own social web of interactions with each other and without one these interactions wouldn't happen. Each person has the acquaintance they would only hang out with if their friend was there.

These interactions are figuratively the same in nature. Predators eat prey and prey eat plants. And let’s not forget about the scavenger who eat what the predators have left behind. Each ecosystem moves together in harmony. Between both direct and indirect motions each animal has an effect on the other. While a beaver might not directly interact with an eagle, they both affect each other indirectly.

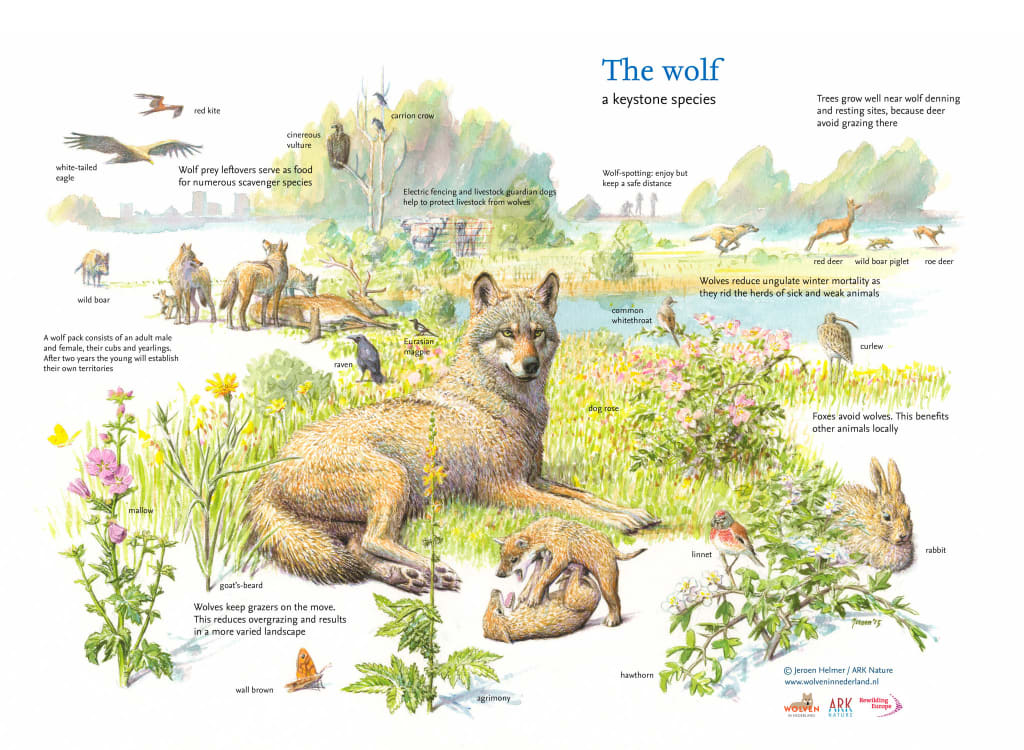

This balance of social systems is kept together by a keystone species. Oftentimes, a keystone species will be a predator due to its ability to control certain populations but this is not always true. They can also be plants in certain areas. For example, the Sonoran Desert;s saguaro cactus is just one. This is due to its ability to provide both food and/or shelter for other species. Biodiversity is often flipped on its side when a keystone species is removed. One population often ends up taking over without the proper chain of events which keeps it under control.

This inmese social web of dependence was first discovered by Zoologist Robert T. Paine in the 1960s. His research focused on trying to understand the food web in Makaw Bay. In doing so, he removed all of the Pisaster ochraceus sea star. The ecosystem changed drastically. Mussels took over the area causing sea snail, limpets, bivalves, and more to be driven out. “Lacking a keystone species, the tidal plain’s biodiversity was cut in half within a year”

(Denchak). One of the most famous examples of a keystone species was the wolves of Yellowstone. When the land was cut out for the national park, people feared what the wolves would do to both the population of elk and their livestock. “The last remaining wolf pups in Yellowstone were killed in 1924” (Nicklen). A top-down trophic cascade began once this occurred. The elk population exploded in Yellowstone. Without a predator, they were able to do as they pleased. Due to their immense grazing, populations of fish, beavers, rabbits, birds, and more decreased since there were not as many vegetation available for them. The elk often ate too quick for the plants to regrow. This overgrazing also caused stream banks to erode due to the lack of wetland plants to anchor soil and sediments. At the time there was a clear line which ran across many trees from the elk eating at the bark. This stunted the growth of many. Since there was little shaded areas from trees and shrubs, lake and river temperatures increased. The physical geography of the Yellowstone Exosystem drastically changed from the removal of just one single species.

“Starting in the 1990s, the U.S. government began reintroducing wolves to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Elk populations have shrunk, willow heights have increased, and beaver and songbird populations have recovered” (Nicklen).

Each ecosystem is built to move in a certain way and if humans are to disrupt that balance there will be a larger increase in extinct animals. There are so many other factors to an environment but keystone species are one of the largest. Yellowstone is just one example of the amazing resilience our ecosystem has. If people can leave the natural balance alone, our ecosystems can restore itself to the great glory it once used to be.

Works Cited

Denchak, Melissa. “Keystone Species 101.” NRDC, 9 September 2019, https://www.nrdc.org/stories/keystone-species-101. Accessed 27 March 2022.

Nicklen, Paul. “Role of Keystone Species in an Ecosystem.” National Geographic Society, 5 September 2019, https://www.nationalgeographic.org/article/role-keystone-species-ecosystem/. Accessed 27 March 2022.

“Wolves of Yellowstone.” National Geographic Society, 30 January 2015, https://www.nationalgeographic.org/media/wolves-yellowstone/. Accessed 27 March 2022.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.