Oliver White Hill, SR (1907–2007)

American Civil Rights Attorney

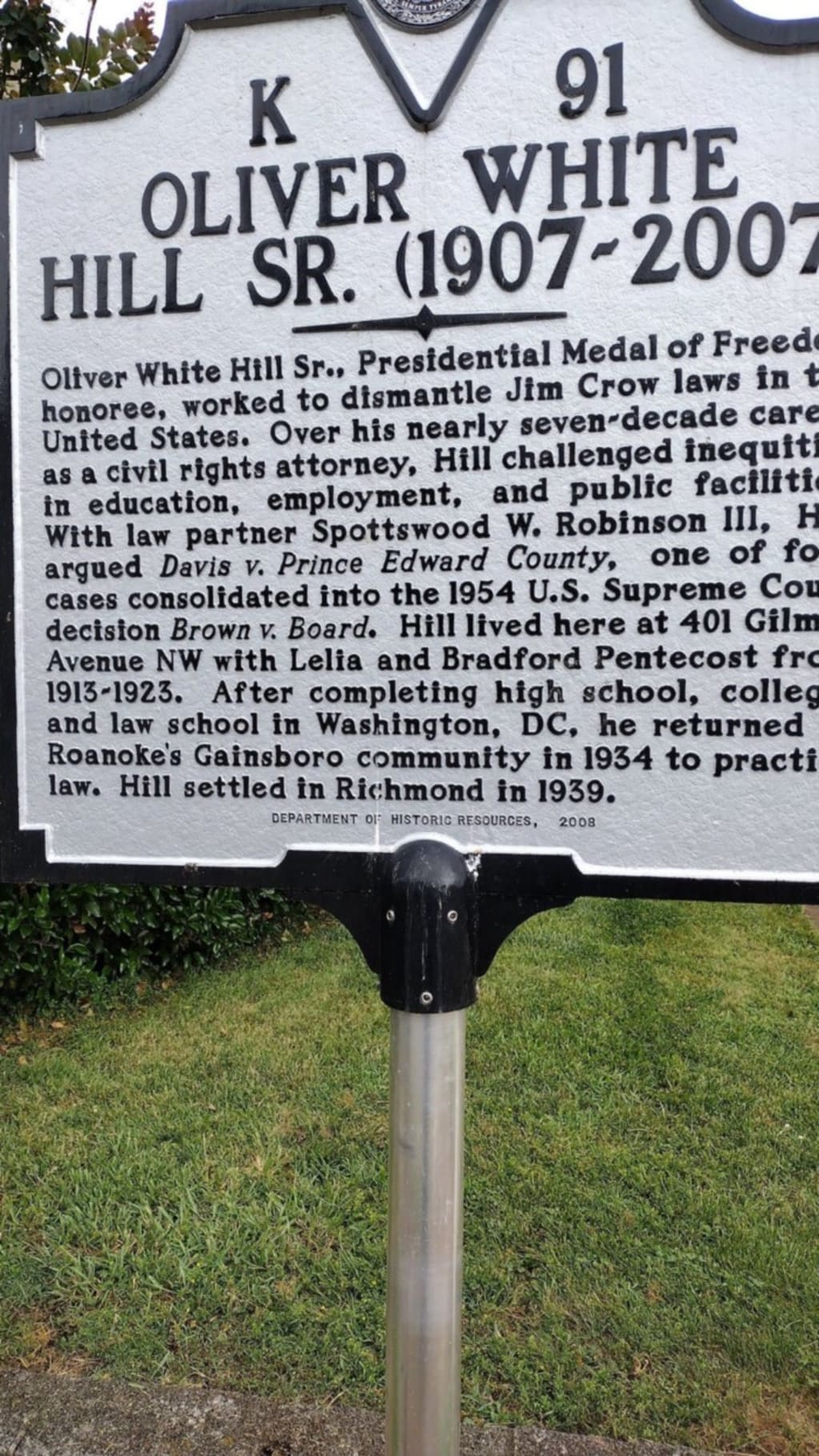

Oliver White Hill, Sr. (May 1, 1907 — August 5, 2007) was an American civil rights attorney from Richmond, Virginia. His work against racial discrimination helped end the doctrine of “separate but equal.” He also helped win landmark legal decisions involving equality in pay for black teachers, access to school buses, voting rights, jury selection, and employment protection. He retired in 1998 after practicing law for almost 60 years. Among his numerous awards was the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which U.S. President Bill Clinton awarded him in 1999. (Source: Wikepedia) Though he spent most of his life working and living in Richmond, he did live in my hometown of Roanoke. The house in which he lived in as a child is just up the road from where I work, in a predominantly African American community. His winning the Presidential Medal of Freedom should have been awarded earlier, but thankfully it wasn’t awarded posthumously.

In 1916, the Hills moved to Washington, D.C., where Joseph Hill worked at the Navy Yard during the First World War. Oliver was in the sixth grade, but he did not like the D.C. elementary school he attended for a semester, and so was allowed to return to Roanoke and his foster parents, the Pentecosts. In 1923, further education being unavailable to him in Roanoke, Hill moved to Washington D.C. to attend (and graduate from) Dunbar High School, which at the time may have offered the best education available to black children in the country. At first Oliver was behind a semester academically, and also lacked scholarly seriousness. He also played various sports-especially tennis in Roanoke, but baseball, football and basketball at Dunbar (which did not have a tennis team).

Joseph Hill’s brother Samuel worked for the post office in Washington, D.C., and in his off-hours worked as a lawyer handling mostly wills and real estate transactions. Samuel Hill died of a cerebral hemorrhage when Oliver was a college sophomore, and his widow gave Oliver his law books, which piqued his interest in law school. Upon learning that the Supreme Court had taken away many rights of African Americans, and that in the 1920s Congress could not even pass legislation outlawing lynching Negroes, Oliver White Hill determined to go to law school and reverse the Plessy v. Ferguson decision issued slightly before his birth.

Hill performed various part-time jobs in D.C. during his college years at Howard University and later the Howard University School of Law. He spent summers earning money for his education at various resorts in the Mid-Atlantic region, including Eagles Mere, Pennsylvania, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and Oswegatchie, Connecticut, as well as for the Canadian Pacific Railway.

After earning his undergraduate degree in 1930, Oliver attended Howard law school. There, Hill was a classmate and close friend of future Supreme Court Associate Justice Thurgood Marshall, although they were leaders of the rival Omega Psi Phi and Alpha Phi Alpha fraternities. Both studied under Charles Hamilton Houston, the chief architect in challenging Jim Crow laws through legal means. Marshall graduated first in his law school class in 1933, and Oliver White Hill second.

Hill courted and married Beresenia Ann Walker (April 8, 1911 — September 27, 1993) of Richmond on September 5, 1934. She taught school in Washington during his early years of practice in Roanoke, and he soon moved back to Washington. She was the daughter of Andrew J. Walker and Yetta Lee Brown, and niece of Maggie Lena Walker. Their son, Oliver White Hill Jr., was born on September 19, 1949, in Richmond, after Hill returned from his World War II service.

Hill began practicing law in Roanoke during the Great Depression, sharing an office with J. Henry Clayer (a lawyer who once worked in the district attorney’s office in Chicago), and a dentist and a physician. It was a general practice and also involved criminal work in surrounding counties, where blacks encountered prejudice. Howard Law School had received funds to challenge segregation of Negroes, but that endowment was nearly wiped out during the 1929 stock market crash. In 1935, Hill helped organize the Virginia State Conference of NAACP branches, with the help of his friend Leon A. Ransom. Printer W.P. Milner of the Norfolk Journal and Guide newspaper was the first President and Dr. Jesse M. Tinsley (a Richmond dentist and president of the Richmond branch) was the Vice-President. When Milner was fired from his job for union activities, Tinsley became the state conference’s President (and remained so for 30 years).

However, the new general practice did not thrive in Roanoke, and he missed his wife, so Hill returned to Washington D.C. in June 1936. He and his college friend William T. Whitehead frequently took jobs as waiters, and also tried organizing waiters and cooks for the Congress of Industrial Organizations because the American Federation of Labor unions were white or segregated.

In 1943, although Hill was 36 years old, somehow, he was drafted during World War II. He chose to join the United States Army, rather than the United States Navy which he thought at the time only allowed black sailors to perform mess-hall duties. Like his partner Samuel W. Tucker and other African Americans, Hill experienced racial discrimination during his military service, particularly by white officers. Unlike Tucker, Hill was not allowed to enlist in Officer Candidate School, but instead served in a unit of black engineers, and performed mostly support duties as a Staff Sergeant. He credited the unprofessional racist comments of the unit’s white chaplain (who tried to stop white English people from fraternizing with the black soldiers) with saving him and his unit from near-certain death during the D-Day Normandy invasion. Hill served in the European Theatre of World War II until V-E Day, when his unit was shipped to the Pacific, from where he was ultimately discharged. (Source:Wikepedia)

I learned of this man in high school and college. One day while walking to work I saw the big white sign marking his house. I stopped and snapped a photo. I vaguely remember what I studied about him. This piqued my interest to find out more about this man, his life, legacy and accomplishments. Anything positive that happens from the neighborhood where he grew up is considered an achievement. Today the neighborhood is downtrodden and most of the kids deal in drugs. Gangs run the neighborhood, totally contrary to what Mr. Hill stood for when he grew up.

As head of the Virginia branch’s legal staff, which also included his law partner Spottswood W. Robinson III and a dozen others, Hill filed dozens of lawsuits over the state. They won over $50 million in improvements for black students and teachers. Hill believed schools could be the crux for desegregation, but he was also a realist, acknowledging that Southern techniques for “getting along” among races both caused whites to believe most blacks preferred segregation, when in fact they bitterly opposed it.

An early case in the Virginia Supreme Court won equal transportation for black school children. In 1951, the team took up the cause of the African American students at the segregated R.R. Moton High School in Farmville who had walked out of their dilapidated school. The subsequent lawsuit, Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, later became one of the five cases decided under Brown v. Board of Education before the Supreme Court of the United States in 1954.

During the 1940s and 1950s, the safety of Hill’s life and family were often threatened as a result of his legal work. Crank calls (many with threats) came all through the day and night until the family learned to take their telephone off the hook at night-time (much to the telephone company’s displeasure, but then it also refused to trace the crank and threatening calls which had provoked that self-help). Hill’s young son was not allowed to answer the telephone, and at one point in 1955 a cross was burned on the Hills’ lawn. I am glad Mr. Hill didn't give into threats, intimidation and fear. Mr. Hill had high moral standards. Today, the Roanoke City Court House is being expanded and renamed The Oliver Hill Court House in his honor.

Nonetheless, Hill and his clients continued their legal battles to assert their civil rights. After the Brown decisions of 1954 and 1955, Virginia’s dominant Byrd Organization adopted a policy known as massive resistance to avoid desegregation. A special legislative session in 1956 passed a legislative package known as the Stanley Plan. This included two special legislative committees with enhanced powers, and which came to harass the NAACP. It also permitted the governor (then Thomas B. Stanley, followed by J. Lindsay Almond) to close schools which desegregated, as well as provided tuition grant support of segregation academies set up to avoid the extant public schools. In 1959, after public schools had been closed in several localities, notably Prince Edward Public Schools, Norfolk Public Schools and Warren County Public Schools, the Virginia Supreme Court and a federal 3-judge panel on January 19, 1959, finally ruled most of the Stanley Plan and Virginia’s law prohibiting integrated public schools unconstitutional. Not long after, Governor Almond abruptly dropped “Massive Resistance” as an official state policy; schools in Norfolk and Arlington integrated peacefully on February 5, 1959, and the schools in Front Royal and all locations except in Prince Edward County reopened. Nonetheless, Prince Edward County schools only reopened in 1964 after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County. (Source: Wikepedia).

This man did more for civil rights than most have done in their lives. Most of what was happening during this was either before I was born or in my infant years. I am proud of the fact that this man stood up against racial intolerance in our country. It takes a special person to stand up against racism and tyranny. This man dedicated his life to standing up for African Americans through his career. I never liked how the military treated the African American soldiers during World War II. I believe we should all learn about this man's life and legacy.

About the Creator

Lawrence Edward Hinchee

I am a new author. I wrote my memoir Silent Cries and it is available on Amazon.com. I am new to writing and most of my writing has been for academia. I possess an MBA from Regis University in Denver, CO. I reside in Roanoke, VA.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.