Mother Tongue Odyssey

A mixed kid's personal account of constantly learning her 1st language.

「うまれじまのくとぅばわしんねーくにわしゅん」

“Umarejima no kutuba washine- kuni washun.”

“To forget the words of the motherland is to forget the land itself.”

It’s an Okinawan proverb I found on one of my research sprints. As a native speaker of Japanese and some Uchinaaguchi, I like to think I’ve been keeping my memories of my land alive.

But I haven’t been able to say I’m fluent.

See, I wasn’t born naturally multilingual. My mother exposed me to Japanese, with some smatterings of Uchinaaguchi. My father engaged with me in English, then as I started school in America, I muddled through ESL (English as a Second Language) classes until I finally tested out in middle school.

I also did not, unlike a lot of Japanese kids living in the States, attend Japanese school, meaning I was always in danger of my Japanese ability atrophying. Attending college away from home and stumbling through phone conversations with my mother and sister assured me of that danger. On top of that, I stinted my own reading and writing ability by asking my mother to stop tutoring me.

Thus why I never felt comfortable calling myself “fluent.”

“You’re doing just fine!” said our Japanese acquaintances. “I’ve been trying to get my son/daughter to speak more Japanese, but they only respond in English.”

So how did you retain it?

Early on—and thankfully—my mother decided she didn’t want to be the only Japanese-speaking member of our multiracial family. She drew upon her schooling back in Okinawa and tutored me in Japanese while I learned English at school.

Like any language course, she started me with the basics.

1. Hiragana and Katakana

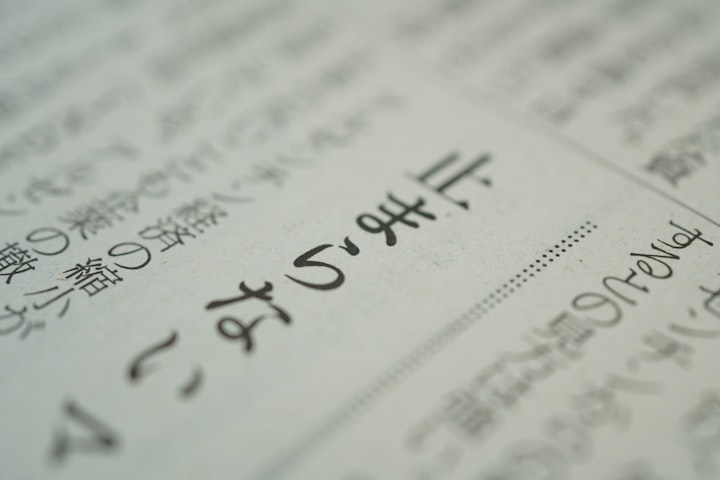

I remember a workbook, vividly colored with the characters ひ・ら・が・な (hi-ra-ga-na) across the cover, and a handmade a calligraphy notebook, bound with yarn and drawn in ballpoint pen, to use for my hiragana drills.

You may often hear that hiragana is the basic Japanese alphabet, 52 characters that form the foundation of the language. I’m sure that’s what 4-year-old me, learning hiragana at the same time as my English ABCs, thought as well.

But it’s an analogy at best. Japanese is more phonetic than symbolic, which my mother demonstrated in the way she taught me hiragana. She read each character to me, helped me trace the proper stroke pattern, then had me repeat the same sound as I wrote the character over and over again. While I wrote, she taught me words and drew pictures, like “ari” (あり, ant) for あ or “ringo” (りんご, apple) for り.

For every single character, even those with extra symbols—like a circle after “ha” (は) for “pa” (ぱ)—or smaller characters—like a small “ya” (や) with “shi” (し) makes “sha” (しゃ)—I ran through the same phonics and writing drills, exercising pronunciations with both hand and mouth.

Come katakana, she applied the same teaching style and took me step-by-step, one character at a time. Look at it, sound it out, write it. Look at it, sound it out, write it. The same base 52 sounds, but with new stroke patterns. My amateur writing made certain characters look exactly the same back then—“shi” (シ) and “tsu” (ツ) or “so” (ソ) and “n” (ン)—and still look the same to this day, but I also don’t face the existential dread I often saw from my classmates in college:

“Can’t we just use hiragana?”

“Why do we have to learn it all again?”

Take it one character at a time. One sound at a time. Write them, say them, follow the proper stroke patterns. For me, learning katakana felt like a hiragana review, meaning kanji should have been no problem for me, right?

Not at all.

2. Listening and Speaking

See, my mother chose not to expose me to kanji until a few years after nailing katakana. Instead, she got worried about my math skills and had me running grueling 10-minute drills on her old soroban (abacus).

But my Japanese studies went on, as my mother spoke to me in Japanese and insisted I respond the same. If I mixed in English, she translated. If I got stuck on a word, she completed my thought. Then I’d repeat the word or sentence I learned, and we’d continue our conversation. Sometimes, she instructed me on intonation, how certain pitches indicated Uchinaabii, or Okinawan tone, versus Japanese. Meaning repetition and exercise, just like writing hiragana and katakana, was the game plan for me here too.

“Nagisa-san,” I hear you comment with your budding expertise, “I watch anime. I never watch dubs!”

TV’s a great resource; I got a lot of my listening practice from TV too. Before emigrating from Okinawa, my mother recorded countless hours of Japanese television—from the Japanese equivalent of Sesame Street to child-friendly anime series to nature documentaries, from talk shows, quiz shows, news segments, contemporary dramas, jidaigeki (period drama), to all the commercials in between.

“This will all be good for you,” my mother once said. “I want you to listen to all kinds of Japanese, since what we speak at home just isn’t enough.”

So I watched them all, no matter how much or little I understood.

“But Japanese TV is so weird outside of anime,” you might think. “I can’t get into it.”

And you may also be wondering why I push so hard for at least listening to Japanese TV, or even Japanese content on YouTube. Part of it is, of course, that it’s just fun to watch a group of guys scrabble through a “don’t get wet” challenge across a water park.

But it also has to do with seeing the language while listening to it. Japan loves its word art, after all.

3. Kanji and the JLPT

By the time my mother attempted to teach me kanji, I was buried under class presentations, book reports, general homework, and of course, middle school drama. All I wanted to do after surviving school was dissociate, and fortunately, my mother took my high grades into consideration and lifted her foot off the language-learning gas pedal. So after learning basic kanji, I put hard pause on my studies.

I should have pushed on.

My very elementary level of kanji, supported only by repeated exposure from TV—remember I mentioned word art—and manga, limited me from calling myself fluent. To remedy this, I took introductory courses at the local community college and struggled to catch up enough for the Japanese Subject SAT.

Still couldn’t read.

I continued those courses at university and learned—but couldn’t remember—new characters. Exams made me nervous, made me question my retention as well as my so-called “native” speaking level. How could the one student in the class who can “perfectly” speak Japanese not score perfectly on tests?

Maybe Japanese wasn’t really her first language.

Yes, someone accused me of lying about my nationality. Someone else spied my less-than-perfect test score and broadcast it to the rest of the class. That was a lovely day.

And I still couldn’t read.

After enough humiliation and hiding my exam results, I got very used to calling my reading and writing ability “elementary at best.” Still I wondered, what was I doing wrong? Why couldn’t I get kanji to stick?

Was it because I wasn’t reading enough? (Yes.)

Was it because I wasn’t doing drills in calligraphy notebooks like my mother used to make me? (Yes.)

Was it because I didn’t have the pressure of an actual mastery exam where I had to demonstrate my knowledge for certification? For me, yes.

Classroom textbooks like Genki or language learning tools like Duolingo introduced plenty of new information, but encouraged very little repetition. Sure, there were rigid examples of conversation and sentences using new words and kanji, but the lessons were also presented as multiple choice problems. Rather than contextualizing and recalling what I learned, I used test-taking strategies instead. I was reviewing rather than learning. So I decided to set a challenge for myself:

JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) certification.

Futile job hunts for Japanese-English bilinguals clued me to this, emphasizing “JLPT N2 preferred” on their listings. I tried a sample test of the N2 level and of course, flunked the kanji and vocabulary portions. “No job prospects for me!” I thought, and chickened right on out.

Then I looked at the N3 level. The presented kanji were more forgiving, a balance of familiar characters and otherwise. Given that I’d need to pay and travel for the JLPT exams, I was set on pressure: I couldn’t invest the time or money and not get certification. Plus, as all tests go, I wanted to see what the test looked and felt like before I challenged the N2.

Then, I rolled up my sleeves, purchased my workbooks, and went back to basics.

I committed to studying kanji the way my mother made me study hiragana and katakana. Drills, pronunciation, review, rinse and repeat. I studied as fast or slow as I wanted, sometimes only learning 4 new kanji a day or as many as 7 or 8. If I already knew the character, I wrote it only 20 times for my drill. Otherwise, I wrote it 60 times. I sounded them out as I followed the stroke order—homage to my maternal grandfather, a licensed shodō master—and made word or picture associations with the on-yomi or kun-yomi of the character. Depending on the complexity of the character, I studied its parts or its pictographic origin. I reviewed kanji from the days before as I flipped to new pages in my workbook. In the month leading up to the JLPT, I purchased a review workbook, downloaded a kanji app, and drilled even more.

I didn’t finish my entire study plan.

But I passed the 2022 N3 exam with flying colors.

The JLPT—at least at the N3 level—really is a matter of “you know it or you don’t.” Test-taking strategies like process of elimination or context clues only somewhat help, a challenge I deeply appreciated. So I’m incredibly, legitimately proud of my certificate. It’s proof that I studied this language and gained some mastery.

Further proof? I’m reading Japanese way better than before—I’m growing more fluent! Meaning I’ve developed a working strategy to use for my N2 studies in 2024. True, I took a break in 2023 to seek personal help and get back into writing, but I also haven’t lost my motivation to continue my kanji studies.

When I explained this to my father after reporting my N3 results, he asked me, “So… how long ‘til you can say you’ve ‘mastered’ Japanese?”

I can get certification for native fluency—N2 certification—this year. Even then, I know I’ll continue learning and re-learning this language every single day. So honestly, the proper answer is,

“Never.”

That’s what I told him, with pride and optimism. After all, this is my mother tongue.

And I will always return home.

About the Creator

Nagisa K.

Afro-Okinawan, a fledgling writer on the path to publication!

Fiction and fantasy are my forte but I dabble in personal essays as well.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.