The alien shrub that can't be stopped

Japanese knotweed evolved in one of the harshest environments on Earth – now scientists are desperately trying to find a way to destroy it.

"After sending a friend several hampers of plants season after season, all without satisfactory results… I sent him some of this," explained the botanist John Wood in 1884. He was writing a gardening manual, and heaped gushing praise on a sensational, newish shrub that that even the most hapless horticulturalist would be able to handle. It was an import from the Far East, and would make a "capital" addition to the small town garden – with pleasing red shoots, handsome heart-shaped foliage, and gracefully arching stems.

In short, Wood had nothing bad to say about the plant – which incidentally, he would soon be selling. Oh and by the way, if you left it alone to grow for a few years, it would form a "charming thicket"…

This was no ordinary bush, of course – it was Japanese knotweed, and there is one glaring detail Wood had neglected to advertise. Aside from its noble, though perhaps slightly over-hyped, aesthetic qualities, it's perversely good value, because once you have it, it's (almost) permanent – it will never die, and without drastic action, future generations will be battling forests of its dense, bamboo-like stems for the coming centuries.

Out of the 13,000 alien species that have made their way around the world since colonialism began in the 15th Century, Japanese knotweed is widely regarded to be among the most intractable – smothering suburban gardens, swallowing up whole swathes of railway line, swamping canals, and creeping into national parks with its searching tendrils.

If this thuggish invader were simply allowed to romp at will, it could swiftly take over the entirety of the UK – except the shady patches where there are trees, says Dan Eastwood, a professor of biosciences at Swansea University in Wales. "I think, if we did leave it, there would be a general domination," he says.

Removing the weed completely is extremely difficult, and essentially involves extracting the land itself – digging at least 5m (16.4ft) deep and disposing of the whole lot almost as if it were radioactive. If anything is left behind, it can return again and again – regenerating from the tiniest of fragments, and ambushing gardeners up to 20 years after it has seemingly vanished. One study found that Japanese knotweed could regrow from a root fragment that's just 0.3g (0.01oz) – around the weight of a pinch of salt.

Unfortunately, you can't just throw some weedkiller on it either. "It could grow back even though it may appear dead," says Kevin Callaghan, the director at Japanese Knotweed Specialists, an eradication company based in London.

"Scientists don't [usually] say never," says Eastwood, but he is willing to take a bold position and say that you never end up killing off an established clump of Japanese knotweed permanently this way – it's literally impossible with the chemicals that are legal. "You've got to admire the plant really," he says.

Aside from the fact that a monoculture of 3m (9.8ft) high weeds isn't everyone's idea of the perfect garden – and it's not exactly ideal for wildlife – Japanese knotweed infestation can have catastrophic financial consequences too.

Each spring, as its asparagus-like tips not-so-tentatively push their way up through the soil, thousands of landowners across the globe turn as green as its foliage – knowing that they might as well have chopped up tens of thousands of pounds and used them as fertiliser.

In the UK, the presence of just a single stem can instantly knock around 5-15% off the value of a house, and lead many banks to refuse a mortgage. The plant has even been known to render properties entirely worthless.

So how does Japanese knotweed achieve its astonishing resilience? And will we ever work out how to vanquish it?

An unpleasant present

On 9 August 1850, Kew Gardens in London received a surprise package in the post.

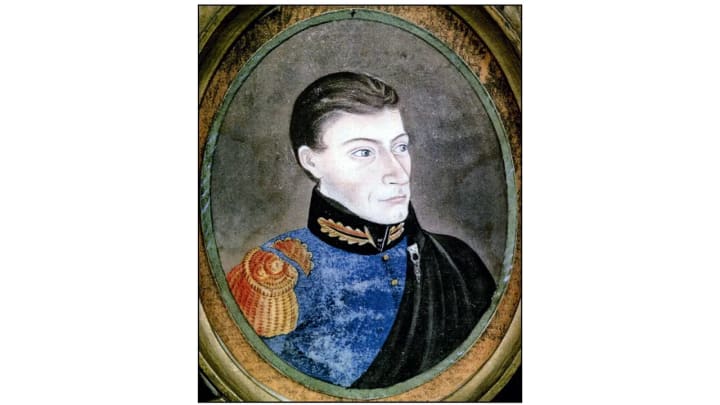

The unsolicited gift contained a number of unusual plants, and a note revealing the identity of the mysterious benefactor – Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold, a German doctor and botanist.

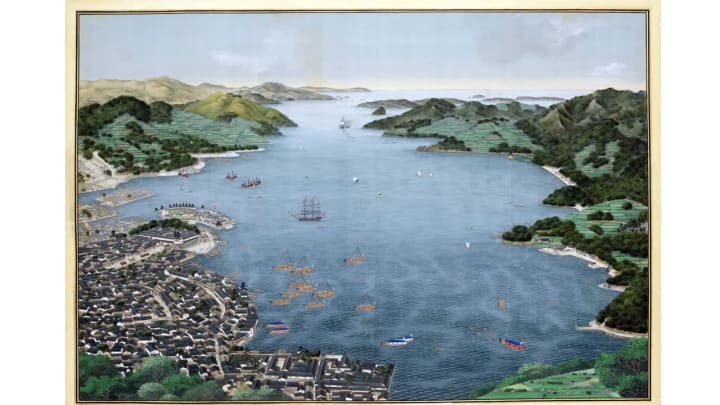

Von Siebold had recently returned from six years on the Japanese territory of Dejima, off the coast of the city of Nagasaki – a trading post built on an artificial island. It was the only point of contact the country had had with the outside world during the isolationist Edo period, when the country closed its borders to foreigners for over two centuries.

As a renowned physician, von Siebold had unprecedented access to a range of contacts in Japan, and used them to indulge his passion for plants – he had people collecting specimens from across the country. But after a rare visit to the mainland and an unfortunate incident involving a prohibited map – which local officials found in his luggage – eventually he was asked to leave.

So, von Siebold packed up some 2,000 plants and came back to Europe. This included a magnificent, sprawling shrub found across Asia, including Japan, Taiwan and South Korea, where it was valued for its uses in traditional medicine and, oddly, as a vegetable. When cooked, its fresh shoots have a tart, fresh flavour similar to rhubarb.

Before long, von Siebold & Company of Leiden was born – a business specialising in the sale of plants from the Far East, based in the Netherlands. And from the outset, Japanese knotweed was one of their star plants. As early as 1847, the Society of Agriculture & Horticulture in Utrecht had awarded this exciting new ornamental plant a gold medal, and a single individual initially cost 500 times more than wisteria – that romantic climbing plant beloved today for its twisted, woody stems and trailing lilac flowers.

It was only natural that this vigorous beauty should be shared with others, and Kew Gardens duly received its very own Japanese knotweed. From there, its conquest was rapid. In this Victorian age of vast estates and colonialist spoils, wealthy landowners were delighted with a Japanese plant that could rapidly fill up space and lend a certain tropical grandeur. The large clumps it formed – known as "stands" – were particularly useful for stabilising sand dunes, feeding cattle, and protecting land from the wind, while its decorative fronds could be added to ornamental bouquets or dried to make matches.

Japanese knotweed was a hit – and within just a few decades, it was sinking its deep roots into the earth across Oceania, North America and much of Europe. Many of these 19th Century clumps still exist today, in the exact same locations they were planted in. It's said that the plant outlives both the garden and the gardener.

According to Eastwood, this early popularity is the first clue to its formidable powers of invasion. "The reality is, it was brought to this country and planted en masse from the Victorian era, over quite a considerable period," he says. "So, when you talk about the numbers of individuals that you put into an ecosystem before it can become established [there], human beings did actually play a big role in that."

It's a scenario that has happened more than once – though today the grey squirrel is often reviled as vermin and compared to a kind of rat, it was once the darling of wealthy Victorian landowners. The species was first brought to the British Isles from North America in 1876 as an exotic curiosity, and has now outcompeted native red squirrels in many areas. But it wasn't brought in once by accident and simply allowed to spread – it was actively introduced, again and again.

In the case of the squirrels, a 2014 genetic study found that these repeated introductions were a significant factor in their successful invasion. Meanwhile, the same is often true of plants.

According to one analysis of floral imposters from 1492 to 2019, gardeners have a lot to answer for – 94% of alien species that have become naturalised outside their home range were cultivated on purpose in residential or botanic gardens. In their quest for unusual new varieties that will grow in their own region, generations of plant enthusiasts have taken specimens from across the planet and actively screened for those that will establish the most easily where they live. Then they've done everything in their power to make it happen. As early as 1856, von Siebold & Company of Leiden's sales catalogue noted casually that that Japanese knotweed is "inextirpable" – a feature they apparently viewed as a benefit.

A hidden repository

However, gardeners don't deserve all the credit. Japanese knotweed is indeed exceptional – a truly out-of-this-world alien invader, from a barren land of lava and toxic gases. The plant's natural habitat is the slopes of volcanoes, where it is one of the first to establish after an eruption. It can sink its famously unstoppable roots into solid, fresh volcanic rock, and there it will lurk for years, clinging on even if its stems and leaves above ground are entombed in incandescent magma.

A world away from this hostile environment, in the coddled paradise that is the average suburban garden, these natural adaptations mean Japanese knotweed is virtually impossible to beat – like a nuclear bomber turning up to a medieval swordfight. And it's this history that's the secret to its determined expansion and impressive survival. (It also explains why it's sometimes able to grow through concrete.)

"Every year, when you get photosynthesis going, and the plant catches light energy, it takes that resource and puts it underground," says Eastwood. The surface parts of a Japanese knotweed plant wither and die back each winter, but its rhizomes – actually a kind of gnarled, modified stem – are still there, nestled into the soil, holding the sugars it made when the going was good. The next spring, the plant sends out new roots to expand its range laterally, and these in turn give rise to more stems above ground. In this way, it gradually creeps along, until it has monopolised every inch of available space.

This two-part system, with above-ground and below-ground body parts, means it's extremely difficult to control Japanese knotweed with chemicals. The most effective is glyphosate, which works by inhibiting an enzyme plants need to produce amino acids, and the best way to use it is counterintuitive. As many homeowners have discovered in their zeal to eradicate the weed quickly, if you use too much, you might accidentally cause the plant to spread.

The part of Japanese knotweed that's visible above ground is the crown – this is the dominant part of the plant that's actively gathering energy. But it has backup. "Surrounding those crowns are dormant buds – so they could potentially lead to new growth, but they don't because they're being suppressed by the crown," says Eastwood. So, if you flood one of these tricky weeds with herbicide, you might kill off the crown completely – and suddenly, all its satellite buds will wake up.

And there's another reason less is more. The best-case scenario with Japanese knotweed is less of a rapid demise, and more of a slow, subtle poisoning – if you apply too much pesticide, the plant will notice something is up and protect its rhizomes. Instead, skilled pest controllers spray or inject the plants with an imperceptible dose on many separate occasions, in a process that takes years – like an Agatha Christie character repeatedly slipping something into their victim's dinner.

"If you kill it off [at the surface], it's not going to spread through the wider plant," says Eastwood. Japanese knotweed colonies may be sprawling, but they're a single interconnected organism – and you can only access the top half, so you need it to remain alive for as long as possible.

"You're almost tricking it into thinking it's back in Japan and it has just been hit by an erupting volcano, and it's putting it back into that dormancy, waiting for the bad times," says Eastwood. Unless you can afford to dig out every last rhizome fragment, for larger stands of Japanese knotweed, tricking the plants into a temporary sleep is the best-case-scenario. Smaller ones may die after several years of treatment – but a proportion will eventually rear their little shoots again, perhaps years or even decades later.

A disasterous liaison

At the moment, all the Japanese knotweed plants in Europe are actually clones of a single, female individual – in fact, they're thought to be genetically identical copies of the specimen that arrived at Kew in 1850.

But though the plant's staggering success is often attributed to this individual's tendency to sprawl laterally – helped along by the occasional establishment of new colonies when soil is moved from one place to another – ironically this asexual spread may be the one thing that has been holding it back.

There are actually several varieties of Japanese knotweed in the UK. In addition to the most common variety, Fallopia japonica var. japonica – around 98% of the plants – there's giant knotweed (F. sachalinensis), dwarf knotweed (F. japonica var. compacta), and others.

None of the regular Japanese knotweed in the UK has been grown from seed, because it's all female. Despite over a century of searching, the vast mother-weed that has colonised Europe – thought to be one of the largest plants in the world – can't find a mate. She just isn’t having sex.

However, there is a possibility – and great fear – that this might change.

While ordinary Japanese knotweed can't hook up with its other female clones, it does occasionally hybridise with the giant and dwarf varieties. This leads to bohemian knotweed (F. x bohemica), which some experts believe is even more invasive than either of its parents. It's still extremely rare in the UK, but it is becoming more common and already found widely in North America, Belgium and Germany.

And there is another threat on the horizon.

The problem is that Japanese knotweed can hybridise with more distant relatives, too, such as the super fast-growing Russian Vine (F. baldschuanica) – a plant that's native to Asia, like its cousin, and grows wild as an invasive species across much of the same range.

"Obviously that is a concern," says Eastwood. "We did see a hybrid [at one of his team's research projects], which was potentially fertile. We killed it before it even got a chance to set seed – we weren't going to allow it to get that far," he says.

Oddly, the hybrid version itself is not particularly invasive – "it kind of takes the worst [i.e. least useful to the plant] traits of the two [types]," says Eastwood. But a liaison between this plant and the original mother variety could theoretically lead to Japanese knotweed that's male – i.e., it could make Europe's lonely female plant a mate. And that could mean big trouble.

Where it does produce seeds, Japanese knotweed is prolific. At one research site in Philadelphia, the plants were found to produce up to 150,000 seeds each year per stem – most of which were found to be viable. So, for now, scientists are just hoping this possible new nightmare era of knotweed offspring doesn't happen anytime soon.

A big mistake

Little did von Siebold know, when he sent that first sample to London, that he would become one of the greatest villains in botanical history.

Unfortunately, Japanese knotweed is not the only alien, invasive plant with a bright future swallowing up vast tracts of the planet. In fact, the two other main weeds currently panicking landowners, governments and environmentalists share some uncanny similarities.

Giant hogweed arrived in the UK in 1819, after seeds were sent over to – where else – Kew Gardens from the Caucasus Mountains in Russia. Today its towering, blotchy stems and umbrella-like white flowers can be seen across Europe and North America, sticking up out of roadside verges, along railway lines and near waterways. Unfortunately, in addition to being invasive, it's extremely toxic – it regularly makes the headlines after unsuspecting passers-by suffer severe blistering and chemical burns from its sap, which is so potent, it can get you from just a light brush of the shoulder.

"We did work for the forestry commission one time in Manchester with giant hogweed," says Callaghan, "and that [patch] was a good few thousand metres square [around 10,000sq ft]."

Himalayan balsam arrived two decades later, after samples were sent to the Horticultural Society of London by a surgeon in India. It quickly became a popular garden plant, prized for its delicate pink, orchid-like flowers and bushy foliage. But within just a few years it had escaped into the wild, and by the turn of the century it was already considered to be a weed.

Together with Japanese knotweed, and many others such as rhododendrons – which are currently taking over Britain's forests – these plants are leading the botanocalypse, the gradual replacement of native plants with those that are difficult to control. And the story is far from over. Though the era of expansive 19th Century gardens and unregulated plant imports are long gone, many plants present in millions of backyards across the world are thought to have invasive potential.

Eastwood is willing to bet that the next big one will be the Japanese anemone. With saucer-shaped pink, purple or white flowers on slender stems, this member of the buttercup family is popular for adding colour to gardens in late summer. But as with Japanese knotweed, it can spread easily underground and quickly take over. Perhaps people won't mind such a pretty invader quite so much – it's certainly hard to imagine a cluster devaluing a house. But if it does come to pass… let's just say you heard it here first.

About the Creator

Vranes Samaha

Living without an aim is like sailing without a compass

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.