Living on Native Land

Years ago, I spotted something on Google Maps that reminded me I wasn't the first person to live on this land--not by a long shot.

Back in the fall of 2014, my then 3-year-old daughter ardently desired to blow off steam after preschool by running into the woods behind our apartment complex. Being tall enough to see the whole area from our back window every morning, I told her there was nothing to see. Our "backyard" consisted of a small wooded area and a marshy, muddy field separating us from I-75, the longest expanse of highway in the country. Still, having seen too many episodes of "Dora," my daughter insisted it was a “magic forest” worth exploring.

My child was very young, but as the daughter of a lawyer and a journalist, she was somewhat responsive to logic. I located our apartment on Google Maps just to show her that nothing was there. Instead, what I saw spooked me. Right behind our building was an empty field—with ruts in the ground in a clear, intentional pattern. To my eye, it looked like the side view of an infant, complete with an eye, an ear, and an open, rooting mouth.

I stared at it for a good ten minutes. What the hell is that? Who did it? I told myself I was seeing things and that it was probably nothing. I already knew my imagination was on the verge of getting me in trouble here. We were, and still are, living in a time of heightened hysteria around “mental illness,” in which people who gravitate toward unconventional thinking are labeled delusional and have their motives questioned. We were also living in a semi-rural Michigan community full of fundamentalist churches that believe occultists and Satanists are a real and active threat. It was Halloween season, so I didn’t want to get my imagination going—or theirs. The only person I showed the image to was my 3-year-old. I asked her what she saw. With a shrug, she grabbed another fistful of Goldfish from her snack cup and said, “Baby.”

The rest of my time in Michigan is a long, complicated story. One thing I look back on and feel proud of, though, was that pattern in the ground. Now that I’m better-educated, I know we were not the first people to live on that land, not by a long shot. The land my apartment complex stood on was once home to the Ojibwe tribe, and the pattern is probably a pictogram.

Not wanting to speak for them, I shared the image with a 10,000-member strong Ojibwe tribe Facebook group. (And thanks to the Ojibwe tribe for letting me join!) I got some interesting comments, with some people agreeing it looked like a pictogram. Others thought it could be a dirt bike path or ATV path. I explained the unlikelihood of it being a dirt bike path, although it could look like one at first glance. The land is marshland and mud that backs up to the highway, with no embankment or guardrails. No one could safely walk back there without proper boots and equipment, which is why I stopped my daughter from trying. The only creatures that tried to go back there: dogs. I could see the highway from my back window, and people had to stop their dogs from trying to dig around in the marsh. While it's not always the case, dogs always trying to dig up a plot of land is a sign of human remains buried there. My theory remains that this is where the Indians buried their babies, back when about a third of children died in childbirth.

Some group members were skeptical that any Ojibwe pictograms had survived the influx of white settlers. To which I say: I get it, to the extent that I am able to get it. I have great respect for the Ojibwe tribe and their traditions, as did my ancestors, including my second great-grandfather who was an Irish immigrant as well as a sailor on the Great Lakes. Patrick Masterson, my ancestor, encountered members of the Ojibwe tribe frequently and sought their advice about sailing and surviving on the lakes. They were the original navigators of Lake Erie, the experts. They taught him sayings like “red sky at night, sailor’s delight; red sky in morning, sailors take warning.” Also: while there are no sharks in the Great Lakes, watch out for the Mishipeshu. The “underwater lynx” was a sea monster feared and revered by the Ojibwe for centuries before white settlers arrived. I wrote a novel based on the real story of my Irish ancestors, and the title, Lake Erie Monsters, is a direct reference to the Mishipeshu. Patrick Masterson’s character in my novel believes in it, respects it—and avoids invading its territory.

“You know he believes in sea monsters,” another sailor said. “Ever since that auld Ojibwa Indian told him about the Lake Erie monster, he’s been scared of ’em.”

“The Mishipeshu,” Patrick corrected them. The Ojibwa insisted the Mishipeshu existed, and Patrick found no reason to doubt them and their millennia of experience on these fearsome lakes.

“Why am I not surprised?” his sailor friend laughed. “When we were at Camp in Detroit, he was on the lookout for the Nain Rouge.”

He hoped the giant underwater panther he’d learned about from Ojibwa Indians in Michigan, the Mishipeshu, would come swallow up Peter Sweeny when he saw him with that gold watch about his wrist. That was what the Mishipeshu did—guarded the precious metals of the Great Lakes, and attacked anyone who threatened his reserves.

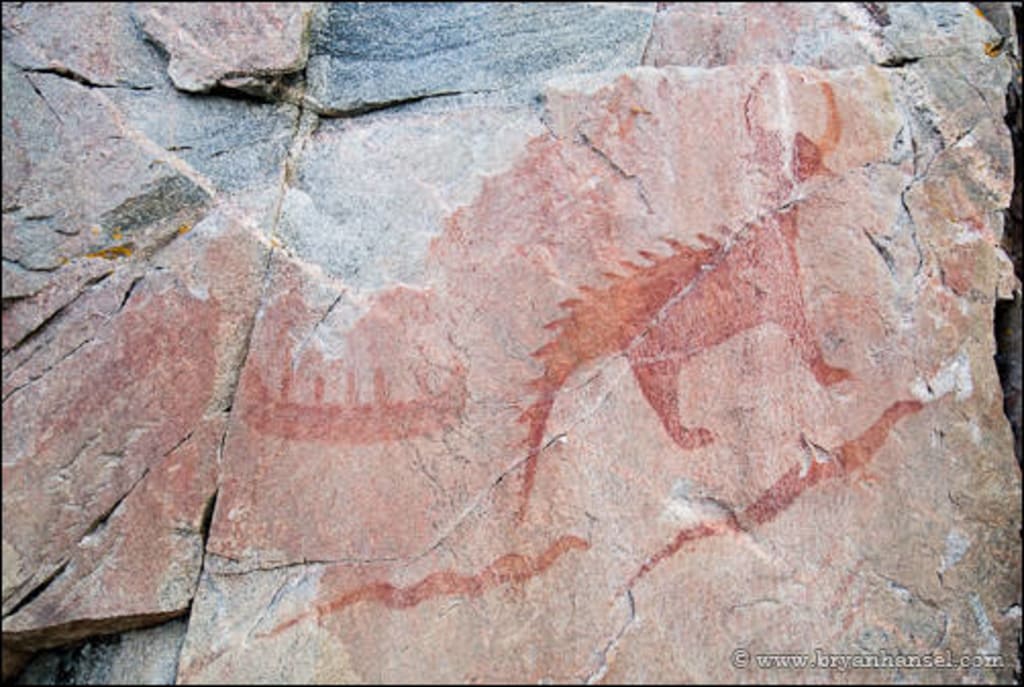

While members of the Ojibwe tribe are right to be skeptical that few of their original pictograms survived, when I started looking on Google Earth, I found more than one possible symbol that still remains. For instance, you can’t tell me this body of water doesn’t look like a deer or an elk with large horns, burrowed into the ground intentionally.

Of course, I will do my best not to overstep my bounds. As I told the Ojibwe tribe members I talked with on Facebook, I’m sharing what I found; I’ll leave the interpretation in their hands. It’s my personal show of appreciation and respect for the original people of the land.

About the Creator

Ashley Herzog

If you like my work, feel free to tip your writer.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.