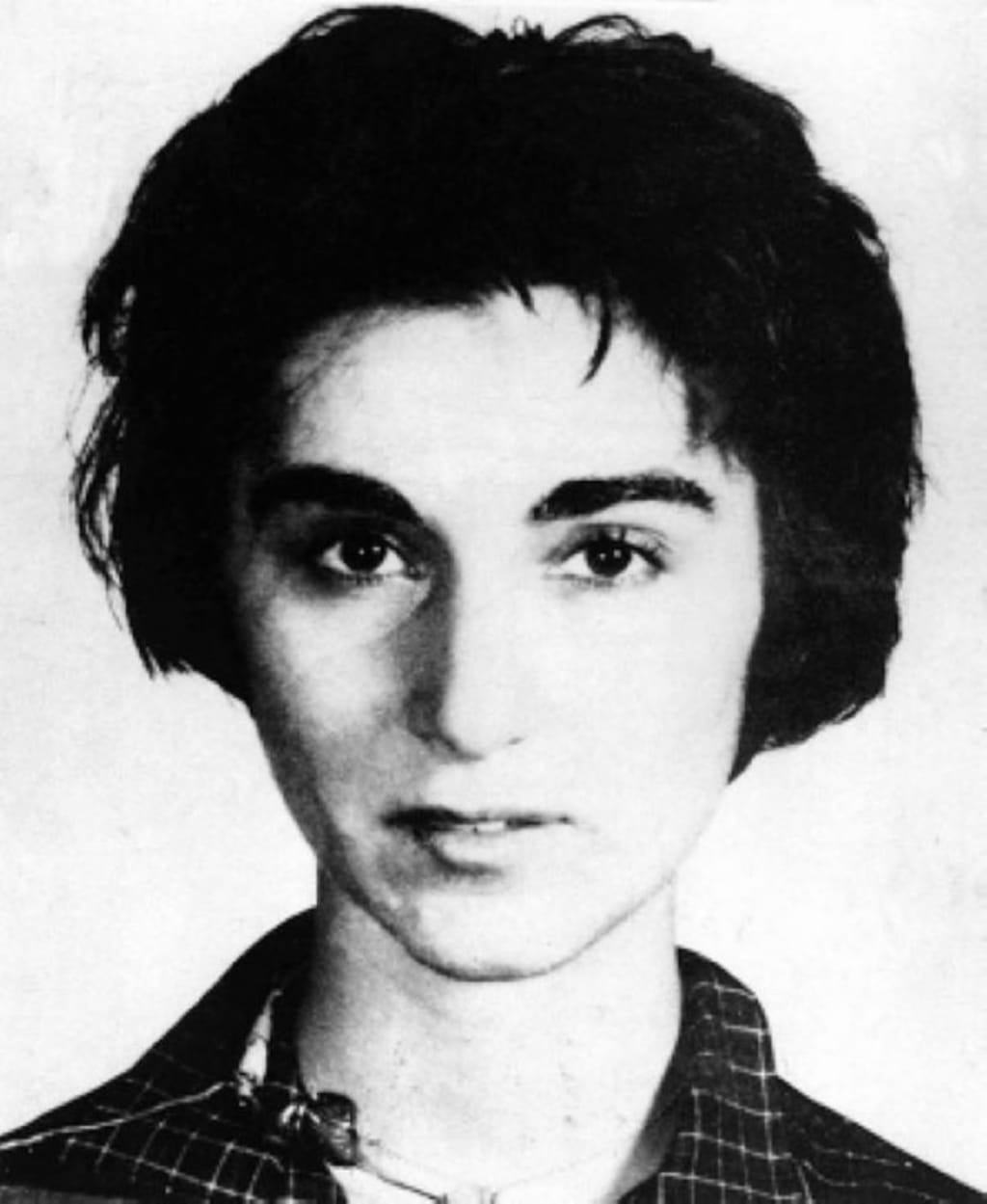

When Lies Become Legend: The Brutal Murder of Kitty Genovese

The true story behind the murder that launched 91 1

What happened?

The scene plays out like a horror novel. A young woman stalked, robbed, raped, stabbed, and left for dead, mere steps from the safety of her home.

Death came for Catherine “Kitty” Genovese during the early hours of March 13th, 1964. There was a chill in the air that cold winter morning when Kitty ended her shift as a bar manager at Ev’s Eleventh Hour Sports Bar. As soon as she clocked off, Kitty got into her prized red Fiat and made the journey to the Queens, New York apartment she shared with her girlfriend, Mary Ann Zielonko.

Kitty had met Mary precisely one year ago, March 13th, 1963, at Swing Rendezvous, an underground lesbian bar in Greenwich Village. The two fell fast for each other and decided to move in together. They found a second-floor apartment together in the middle-class neighborhood of Kew Gardens, Queens. It was considered a peaceful, safe area to live. Kitty had been eager to get home and see Mary on their first anniversary.

However, unbeknownst to Kitty, 29 years old married father of three Winston Moseley was lying in wait. Winston had spotted Kitty at a red light after she left her job and decided to trail Kitty to her residence.

When later questioned about his motive, Winston would admit that he simply wanted “to kill a woman.”

After Kitty exited her car, she was approached by a knife-wielding Winston. Frightened, she ran towards the front door of her apartment building, but Winston was able to catch up. He grabbed Kitty and stabbed her twice as she screamed in fear. At this point, neighbor Robert Mozer yelled out his window, “Let that girl alone!” causing Winston to flee and drive off.

Unfortunately for Kitty, Winston returned approximately ten minutes later when the coast was clear. By this point, a wounded Kitty had made her way to the back of her two-story residence, but critically, out of sight of witnesses. In a hallway at the rear of the building, she lay barely conscious, stymied by a locked door that prevented her from going inside. Winston eventually found her, stabbed her several more times, raped her, and robbed her of $49 before running off. Kitty would later die in the ambulance ride to the hospital. The entire ordeal took 35 agonizing minutes.

Kitty could never have envisioned the tremendous effect her death would have on society.

Vilified by the media

Two weeks after Kitty’s death, The New York Times “reported” on the crime with an erroneous front-page article exclaiming, “37 WHO SAW MURDER DIDN’T CALL THE POLICE.”

Unfortunately, for the residents of Kitty’s apartment, the story was incredibly flawed. But it was never really about the facts. The New York Times wanted to sell a story. A story of the 37, later amended to 38, neighbors who saw a woman being attacked and did nothing.

This legend of Kitty Genovese and her apathetic neighbors was primarily concocted by NYPD commissioner Michael Murphy and New York Times city editor Abe Rosenthal over lunch at Emil’s Restaurant and Bar.

Abe Rosenthal recalled the conversation he had with the commissioner:

“Brother,” Michael Murphy said, “that Queens story is one for the books. Thirty-eight people had watched a woman being killed in the ‘Queens story,’ and not one of them had called the police to save her life.”

‘Thirty-eight?’ I asked.

And Michael Murphy said, ‘Yes, 38. I’ve been in this business a long time, but this beats everything.’

Little did they know how this story would change a nation.

Decades later, The New York Times would admit that many of the facts in the article were untrue. Due to the layout of the apartment complex and because the attack happened in two parts, no one saw the entire sequence of events. Additionally, only a dozen people saw or heard the attack, not the 38 reported. The newspaper further acknowledged that the interviewed residents did not know a murder was taking place and assumed it was two lovers or drunks quarreling in the streets. More profoundly, two residents did call the police!

A 15 years-old boy, Michael Hoffman, claimed his father called the police after the first attack and relayed that a woman was “beat up, but got up and was staggering around.” However, the police did not respond, and the local precinct had not logged the call. Michael’s father was given a dirty look by detectives the next day when he stated, “maybe you should have come when I made the phone call.”

The second phone call came after the final attack, and the police arrived on the scene within minutes.

The aftermath of the murder

Kitty was just one of New York’s 636 murders in 1964. Yet, she became more than a statistic. Kitty’s murder was a symbol of the consequences of inaction and indifference.

Her death scared New Yorkers, sparking conversation about modern urban life's isolation and moral soullessness. After the sensationalist New York Times article came out, many were left incensed that not one of her neighbors bothered to lift a finger to call the police or come to her aid.

After the New York Times broke the lid on the murder, the case gained national attention when Life magazine chimed in on the debacle. Journalist Loudon Wainwright referred to the residents as “38 heedless witnesses” in his column, “The Dying Girl That No One Helped.”

“If the reactions of the 38 witnesses to the murder of Catherine Genovese provide any true reflection of a national attitude toward our neighbors, we are becoming a callous, chicken-hearted and immoral people.”

The public sentiment was clear. Her community had grossly failed Kitty Genovese. While the truth would come five decades too late for the vilified residents in Kitty’s apartment building, the inaccuracies in the article were beneficial for society. The fallout from Kitty’s murder is often cited as a major driving force for the creation of the 911 emergency call system, allowing witnesses a quicker and easier way to report a crime.

Creation of 911

Today, it is commonplace to call 911 in the event of an emergency. However, that was not possible in 1964. Back then, there was not a centralized number for U.S. residents to call. If you wanted the police or fire department, you either looked up and dialed the number for the local precinct or dialed “0” to reach a telephone operator and then be connected. What’s worst, the emergency number for the local police/fire department was often the same as the non-emergency number, meaning a busy signal was always a strong possibility.

In 1967, the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice recommended a system by which U.S. citizens could contact emergency services utilizing a single telephone number.

The President’s Commission turned to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for a solution. The FCC, in turn, met with AT&T in November 1967 to find a means of creating a national emergency number that could be implemented quickly. By 1968, AT&T, which at the time operated nearly all telephone connections in the U.S., established the 911 line.

The strangest 911 calls

Since the 911 emergency line was created over 50 years ago, an estimated 240 million calls have been made each year in the USA. As can be expected, there have also been many strange and weird calls taken over the years.

One 911 operator told People magazine that a man called emergency services because there was an aggressive squirrel next to his car and he couldn’t get in. However, the squirrel left before the police got there.

Over in British Columbia, one resident called 911 to complain that their neighbor was vacuuming late at night, and another complained because a gas station wouldn’t let them use the washroom.

In December 2017, a man called 911 twice to complain about the size of his clams at a seafood restaurant in Stuart, Florida.

A robber in Shelby Country, Ohio pocket dialed police while he was breaking into a property. He proceeded to hide in the closet, but when police arrived, his phone’s ‘low battery’ alarm went off- giving him away.

A man who escaped from police custody in Iowa was captured in Illinois in October 2014 after calling 911 to report 20 or 30 coyotes were chasing him.

About the Creator

Chelsea Rose

I never met a problem I couldn't make worst.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.