True Story - The real story of Collar Bomb Heist 2003

A true story of Collar Bomb Heist.

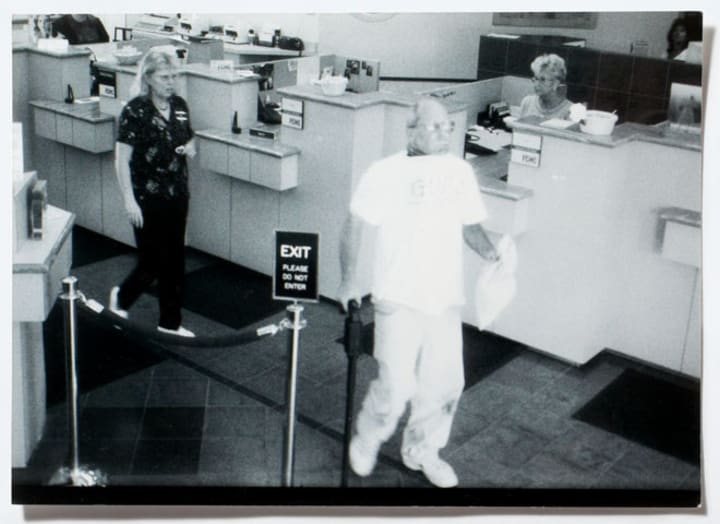

A middle-aged pizza shipper named Brian Wells walked into a PNC bank in Erie, Pennsylvania on August 28, 2003. His right hand had a small cane, and under the collar of his T-shirt was a peculiar bulge. Wells, 46 and balding, handed a note to the teller. "Gather workers with vault access codes and work quickly to fill the $250,000 bag," it said. "You just have 15 minutes." Then he lifted his shirt to expose a bulky box-like gadget hanging from his throat. It was a bomb, according to the note.

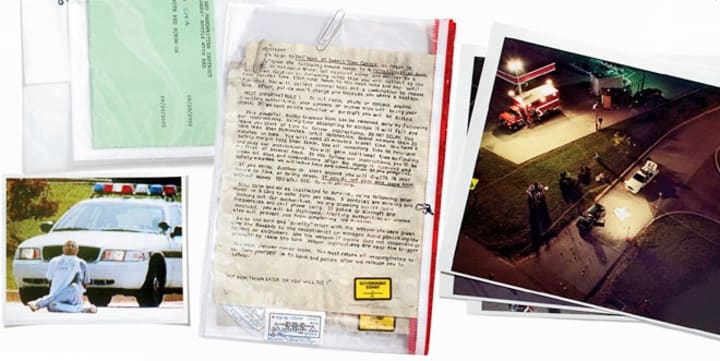

The teller, who told Wells that at that time there was no way to get into the vault, filled a bag with $8,702 in cash and handed it over. Wells walked out, sucking a lollipop of Dum Dum, which he picked up from the counter, jumped into his car, and sped away. He hasn't gone far. Approximately 15 minutes later, state troopers found Wells standing in a nearby parking lot outside his Geo Metro, surrounded him, and threw him to the ground, cuffing his hands behind his back.

Wells informed the troopers that a gang of black men, who chained the bomb around his neck at gunpoint and forced him to rob the bank, had assaulted him while he was out on a delivery.

"It will go off!" he told them in despair. "I'm not lying." Calling the bomb squad, the officers took positions behind their cars, drawing weapons. Television camera crews arrived and started filming. Wells stayed sitting on the pavement for 25 minutes, his legs curling underneath him.

Have you called my boss? "Wells asked a trooper at one point, obviously worried that his employer may have felt that he was shirking his duties." The computer began to emit an escalating beeping noise unexpectedly. Fidgeted Wells. It looked like he was trying to scoot backwards, the explosive tied to his waist, to escape somehow. Beep — Beep ... Beep — Beep ... Oh. Beep. Uh, boom! The system exploded, violently blasting him on his back and tearing a 5-inch gash from his chest. A few last gasps were taken by the pizza deliveryman and died on the pavement. It happened at 3:18 pm. Three minutes later, the bomb squad arrived.

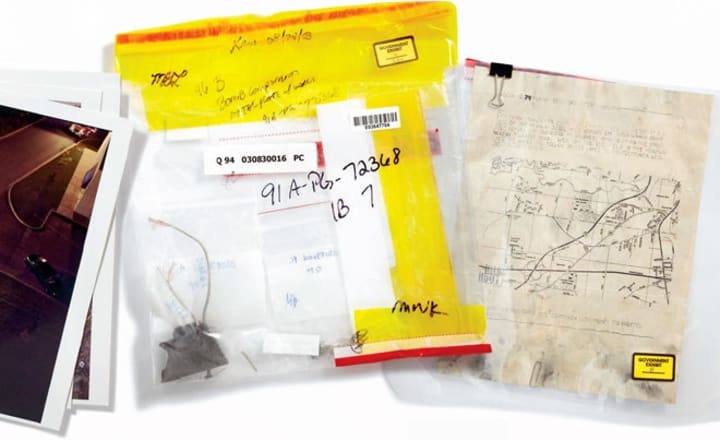

However, the most perplexing and interesting pieces of evidence were the handwritten notes discovered inside Wells' car by investigators. Addressed to the 'Bomb Hostage,' the notes told Wells to steal $250,000 from the bank, then follow a series of complicated instructions to find different keys and combination codes concealed in Erie. It included sketches, intimidation, and maps with information.

If Wells did as he was told, he would end up with the keys and the combination needed to free him from the bomb, the instructions promised. In certain death, failure or disobedience will result. "The notes read in meticulous lettering that would later stymie handwriting analysis:" There is only one way you can survive and that is to comply fully.

"Only by following our instructions can this heavy, booby-trapped bomb be removed ... ACT NOW, THINK LATER OR YOU WILL DIE!" It seemed that whoever planned the robbery had also created a nightmarish scavenger hunt for Wells, in which his life was the prize.

The cops attempted to complete the search themselves in the frantic hours after Wells was killed. "The first note was clear enough: it read," Exit the bank with the money and go to the McDonald's restaurant [sic]. "Get out of the car and go into the flower bed to the small sign reading drive thru / open 24 hr. There is a rock with a note taped to the bottom by the sign. It has your next directions."

Wells drove straight there with the bag of cash after he left the bank. He picked up a two-page note from the flower bed that led him up Peach Street to a wooded area a few miles away, where the next set of directions would be kept in a container of orange tape. Before he got to that clue, Wells was trapped, but the investigators picked up the thread, with the orange tape finding the jar.

They found a note in it pointing them 2 miles south to a small road sign where the next clue will be waiting in a jar nearby in the woods. They noticed the jar when they got there, but it was clean. It seemed like everyone who had set this macabre ordeal in motion had called it off until the cops arrived and had probably followed them every step of the way.

The clothes of Wells added another layer of mystery. He died wearing two T-shirts, the outer one emblazoned with the logo of a Guess dress. Wells didn't wear a shirt that morning at work, and his relatives said that it wasn't his. It seemed like a taunt: Can you guess who's behind it?

That was just one of the questions that made investigators perplexed. What was the intention of the scavenger hunt, for example? Why send a hostage in broad daylight, hopping around Erie? Why scatter clues where they could be discovered in public locations? How was Wells picked as the hostage?

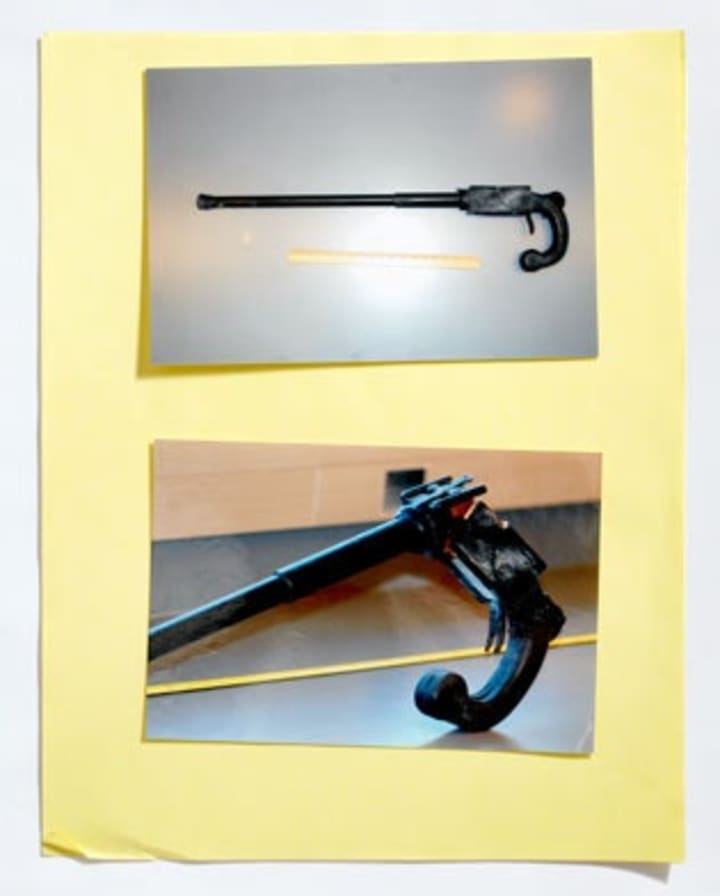

The police started to dig through a trove of physical evidence. They found the 2-foot-long cane in Wells' car, which turned out to be an ingeniously designed homemade knife. Likewise, the bomb itself was a marvel of DIY design and construction.

The package consisted of two parts: an iron box containing two 6-inch pipe bombs loaded with double-base smokeless powder, and a triple-banded metal collar with four keyholes and a three-digit combination lock. The hinged collar secured like a giant handcuff around Wells' neck. Investigators were able to conclude that it was designed using specialised instruments.

There were also two Sunbeam kitchen timers and one electronic countdown timer on the unit. It had wires that led to nothing-decoys to throw off would-be disablers-and stickers with misleading warnings-running through it. In and of itself, the contraption was a puzzle.

The riddles transfixed the town of Erie and drew attention from St. Louis to Sydney in newspapers. A Byzantine investigation was also set in motion, with federal officers sniffing for clues and tracking down leads in the twisted search of the shadowy suspect who became known as the Collar Bomber. The FBI had been engaged in a scavenger hunt of its own for seven years, one that the Collar Bomber seemed to have organised as intricately as the one Wells had ensnared. Whether the Feds would get much farther than Wells had was the only question.

At Mama Mia's Pizza-Ria, the search started. That's where Wells served on the day of the robbery at 1:30 pm, when an order for two small sausage-and-pepperoni pies to be shipped to a spot on the outskirts of the city came in. In 10 years, the only time he had called for work late was when his cat died. Wells was a faithful employee. He decided to deliver the order even though he was at the end of his shift. He walked out of the shop at about 2 pm, two pies in hand.

A TV broadcast tower site in a forested area off busy Peach Street was the distribution spot, accessible only by a dirt track. They found shoe prints consistent with Wells' boots and tyre tracks matching the treads on his Geo Metro when investigators combed the vicinity. The web, however, gave no clues as to who may have lured him there or what happened once he arrived.

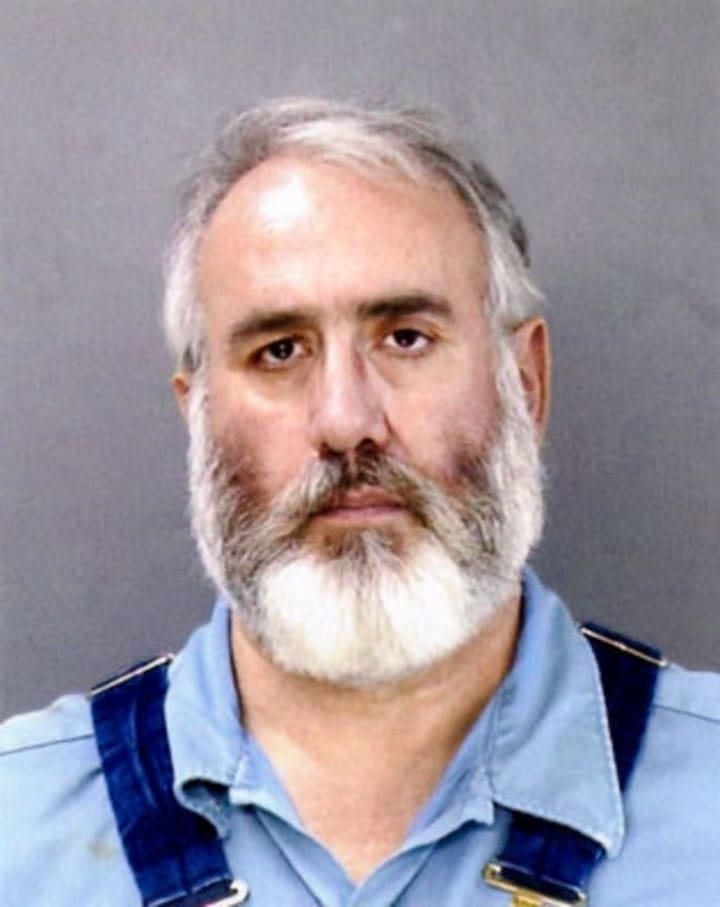

The next day, a reporter and an Erie Times-News photographer went to the tower. Authorities cordoned off the dirt road leading there, but the journalists spotted a tall, heavy-duty man pacing in denim Carhartt overalls in front of a home sitting right next to it. His backyard almost stretched to the transmission pole. The man described Bill Rothstein as himself.

Rothstein, 59, was a handyman who was single and a lifelong local resident. Like someone who takes great pride in his mastery of the English language, he spoke elegantly. (He was fluent in French and Hebrew as well.) Rothstein appeared unaware of the inquiry going outside his backyard. Eager to get a glimpse of the scene, the journalists asked Rothstein if he would be able to lead them through his yard. He consented. They were going into the dense brush, but they couldn't see anything yet. They took off after spending about 15 minutes at Rothstein 's house.

It might appear that Bill Rothstein was just a man who owned a house next to the TV tower. He turned out, however, to be keeping a dark secret. Rothstein called 911 on September 20, less than a month after the bomb had killed Wells. "There is a frozen body at 8645 Peach Street, in the garage," he told the police dispatcher, referring to his own address. "In the fridge, it is."

Rothstein was in detention within hours of making the call. He told the cops that for weeks he'd been in pain. He had considered killing himself, he told them, and had gone so far as to write a suicide note, which police had found at his home inside a desk. "Rothstein expressed his apology in black marker" to those who cared about or for me, "described the body as that of Jim Roden in his freezer, and noted that he" did not kill him or participate in his death. "The note opened with a strange disclaimer:" This has nothing to do with the case of Wells.

Rothstein explained to the police for the next two days how there was a dead man in his freezer. He said he had received a phone call in mid-August from a former girlfriend, Marjorie Diehl-Armstrong, who he had been dating in the 1960s and early 1970s. Diehl-Armstrong told him that she had shot James Roden, her live-in partner, in the back with a 12-gauge Remington shotgun in a money dispute.

She needed assistance now to remove the body and clean up the scene inside her home in Erie, about 10 miles from Rothstein 's house. What she asked, Rothstein did. For five weeks, he kept the body in a chest freezer in his garage. He melted the murder weapon painstakingly and dispersed the pieces throughout Erie County. But, Rothstein said, with the intention to grind the body, he could not go through it, and he called 911 because he was afraid of what Diehl-Armstrong could do to him.

Diehl-Armstrong was arrested on September 21 for the murder of Roden, the day after Rothstein called 911. Sixteen months later , in January 2005, she pled guilty to mental illness and was sentenced to seven to twenty years in state prison. At that time, however, Rothstein had taken care of the old girlfriend he had offered to the cops: in July 2004, he had died of lymphoma.

The federal agents' team investigating the mystery of the collar bomb had not paid much attention to the Roden murder. It was a local matter, and their case seemed to have nothing to do with it. But they received a phone call in April 2005 from a state police officer who had just met Diehl-Armstrong about an unrelated murder.

The suicide note from Rothstein, it seemed, was a lie; Diehl-Armstrong had said that the murder of Roden had something to do with the plot of the collar bomb. When the Feds met with Diehl-Armstrong, she told them that she would tell them everything she knew if they could negotiate a move from Muncy State Penitentiary to the Cambridge Springs Minimum Security Prison, a facility far closer to Erie.

Diehl-Armstrong was one of Erie's most infamous figures, well known for her string of dead lovers, long before she was arrested for killing Roden. She first attracted national attention in 1984 when, at 35, she was accused of murdering Robert Thomas, her boyfriend. Diehl-Armstrong argued that she had shot him in self-defense six times, and she was ultimately convicted by a jury. Four years later, Richard Armstrong, her husband, died of a cerebral haemorrhage. The death was ruled accidental, but concerns lingered; when he arrived at the hospital, Armstrong had a head injury, but the case was never referred to the coroner's office.

Back in high school, Diehl-Armstrong was known for her sparkling intellect, according to former classmates, and she also had an almost encyclopaedic knowledge of literature , history, and law. But the genius had been, over the years, spiked with madness. She was suffering from bipolar disorder, according to court documents.

Her mood swung sharply, and her nonstop, rapid-fire speech seemed incapable of controlling her. She was arrogant and paranoid. Investigators discovered 400 pounds of butter and more than 700 pounds of cheese inside her trash-strewn house in 1984, almost all of it rotting. Before a judge eventually found she was fit to be prosecuted in the Thomas case, doctors considered her mentally ill seven times.

She seemed to be precisely the kind of person who might devise an unnecessarily complex bank heist, murderous, eccentric, and bent on demonstrating her intellectual gifts. She also seemed to be the kind of person who would definitely not be able to avoid telling the world about her clever ruse.

As Diehl-Armstrong met for a series of interviews with federal prosecutors, that was just what she seemed to be doing. Although insisting that she was not involved in the scheme in any way, she admitted that she knew about it, that she had supplied the kitchen timers that were used in the bomb, and that at the time of the robbery, she was within a mile of the bank.

She also said that not only was Wells, the dead pizza delivery man, a survivor, but he had been on the schedule. And so was Rothstein, the man who had turned her over for the murder of Roden. In reality, he had masterminded the whole thing, she said.

But even though Diehl-Armstrong pointed her finger at Rothstein, she got involved. Indeed, investigators had started to believe, long before hearing her self-incriminating testimony, that Diehl-Armstrong was behind the collar-bomb attack. They had spoken with four different informants during the past few weeks, who confirmed that Diehl-Armstrong had spoken intimately about the crime. One kept records of the conversations, which included the statements of Diehl-Armstrong that she killed Roden because "he was going to speak about the robbery" and that she had helped measure the neck of Wells for the bomb.

Then they got another break in the case in late 2005, a few months after Diehl-Armstrong first spoke to the Feds: a witness came forward to say that an ex-TV repairman turned crack dealer named Kenneth Barnes was also involved. Barnes, Diehl-Armstrong 's old fishing friend, had talked too frankly about the scheme, and had been turned in by his brother-in - law when Barnes was still in gaol on unrelated drug charges. Threatened with yet more time behind bars, Barnes agreed to a deal: in exchange for a shortened sentence, he would provide a detailed account of the crime.

Barnes reiterated the Feds' suspicion that the mastermind behind the collar bomb conspiracy was Diehl-Armstrong. He said that she needed the cash so that she could pay him to kill her father, who she believed was blowing money that she expected to inherit from his fortune. He was kept in the dark about certain aspects of the storyline, Barnes insisted. But his account, even with gaps, corroborated most of what the agents had learned already. Lastly, the investigation was gathering steam.

Federal agents met again with Diehl-Armstrong on February 10, 2006, who had brought in her attorney. The agents informed Diehl-Armstrong that they had ample proof to bring an accusation against her. She went ballistic, pounding a conference table with her fist and cursing the agents and her lawyer. Yet, incredibly, she kept on talking to them.

She also decided to drive around Erie with them in a subsequent meeting to point out where she was the day Wells robbed the bank. At the end of the drive, in which she confessed to being connected to the crime at several locations, Diehl-Armstrong told the agents that without obtaining an immunity letter, she would not provide any more details. It was pretty late. The woman who couldn't stop speaking had said way too much already.

The US attorney's office in Erie called a news conference in July 2007, a month shy of the four-year anniversary of Wells' death by collar bomb, about "a major development" in the case. U.S. attorney Mary Beth Buchanan, standing before a TV cameras bank, declared that the investigation was over. Diehl-Armstrong and Barnes, a scheme that Diehl-Armstrong had set in motion, were charged with carrying out the sensational crime.

The indictment also alleged that it included other conspirators. One was Rothstein. And the supposed perpetrator, Wells, was another. Gathering information obtained over nearly four years from more than a thousand interviews, the indictment charged that Wells was in the system from the beginning. He had decided to rob the bank with what he claimed to be a fake bomb. He was advised that the scavenger hunt was just a ruse to trick the cops; if he got caught, he could point to the threatening instructions as proof that he was only following orders.

But over time, Buchanan said, Wells went from being a strategist to "an reluctant participant." At some point, Wells was double-crossed and actually became one instead of merely playing the part of a hostage. It turned out the fake bomb was a legitimate one. And the scavenger hunt went from a clever misdirection to a race against the clock in real-life. Wells' family looked shocked while seated in the press section. As Buchanan completed her point, one of his sisters, Barbara White, shrieked "Liar!" repeatedly.

Wells' kin were not the only dubious ones. The government's long-awaited announcement was severely unsatisfactory for those who closely followed the situation. As many questions as it replied seemed to prompt it. Why would Wells engage in a plot like that? Did he know the danger in which he was? And could Diehl-Armstrong really plan such a complex crime, with her myriad mental issues? Just a week later, when it was revealed that the FBI had concluded that the whole scavenger hunt was a hoax, did the questions multiply. The bomb was rigged so that it would be set off by any attempt to extract it. Wells' fate was to die.

Barnes pleaded guilty to the conspiracy and firearms charges involved in the collar bomb plot in September 2008. He was sentenced to 45 years behind bars, but in the hope of minimising his term, he decided to testify against Diehl-Armstrong.

The trial of Diehl-Armstrong vowed to clear up the mystery surrounding the collar bomb case. But he'd have to wait for those discoveries. Second, Diehl-Armstrong was found mentally incompetent to face trial by a federal judge. She was diagnosed with glandular cancer when she was eventually considered fit to face a judge and jury, and the treatment was placed on hold again as she awaited her prognosis. The doctors' assessment was received by the judge in August 2010: Diehl-Armstrong had three to seven years to live. The prosecutors decided to move ahead, and the trial was rescheduled to take place on 12 October.

Most intriguingly, Douglas Sughrue, Diehl-Armstrong 's counsel, had agreed to let his client take the stand. It was a risky move, it seemed. She had already implicated herself in the assassination, after all. Was it prudent to invite such an volatile, chaotic personality to testify?

Ken Barnes took the stand on day five of the trial in the Erie Federal Courthouse. By this time, an impressive argument had already been constructed by the prosecutor, Marshall Piccinini, a fast-talking, silver-haired assistant US lawyer. Piccinini had trotted out seven former inmates who recalled incriminating details that Diehl-Armstrong had shared with them, summarising the odd characters connected to the Wells storey as a cast of "twisted, intellectually bright, unstable individuals who outsmarted themselves." Piccinini's star witness, and his last one, was Barnes, the ex-crack dealer and would-be hit man.

He was also the guy who seemed willing, eventually, to say the whole storey of what had happened in the days leading up to the day of the robbery on August 28, 2003. Barnes, who had the wan face of the former crack addict he was, and a small set of teeth, approached the bench and took an oath. He then sat in the witness box and explained the conspiracy to a rapt jury matter-of-factly.

Diehl-Armstrong devised the strategy, Barnes said, and enlisted a few coconspirators to help execute it. One of them was Rothstein. Wells was another, drawn in with a payday pledge. He needed the capital, surely. The quiet pizza man turned out to have had a relationship with a prostitute. He purchased cocaine, with the help of his pal Barnes, which he then gave to the prostitute in return for sex.

But Wells fell into debt with his crack dealers in the weeks prior to the robbery and needed cash. Wells discovered that he had been double-crossed and that the bomb was real only on the afternoon of the murder, when he had delivered the pizzas to the TV transmission tower. As he tried to run away, he was tackled and locked at gunpoint inside the unit.

Diehl-Armstrong angrily whispered to her counsel during Barnes' testimony. She blurted out "Liar!" several times, earning stern warnings from the judge. To all appearances, listening to people like this discredit her was excruciating for her.

Diehl-Armstrong eventually got the chance to share her version of events on October 26, the eighth day of the trial. She used the witness stand as her stage for five and a half hours over two days. Her black wavy hair looked greasy, sticking to the sides of her face. She unleashed a flood of words each time she opened her mouth. "That's a dumb question, Mr. Sughrue," she mocked her lawyer. She belittled the prosecutor, "If this is the kind of evidence you have against me, I 'm telling you, this is a pitiful case." She cried out. She screamed. The judge tried, mostly futilely, to cut her off more than 50 times.

She addressed Brian Wells only once during her first day on the stand, in the final 10 minutes of an almost 100-minute-long diatribe: "I never met Brian Wells, and I never knew Brian Wells. Never. The day he died, I became aware of him. I saw it on the television."

It didn't buy the jury. The seven women and five men returned guilty verdicts on all three counts after deliberating for 11 hours: armed bank robbery, conspiracy, and use of a destructive weapon in a crime of aggression. When she is convicted on February 28, she will face a mandatory life term.

The unanswered questions were eventually answered after seven years. At least, that's how most people interpreted the conviction of Diehl-Armstrong. But that isn't how things are seen by Jim Fisher. A former FBI forensic investigator, after seeing video of Wells squirming on the pavement with the gadget yoked around his neck, Fisher began closely monitoring the collar bomb case.

The then-64-year-old professor of criminal justice had everything to do with unsolved murders, and it was one of the most staggering crimes he'd ever seen. He obsessively pored through the case's media reports and reviewed every piece of evidence that the FBI released. And, according to Fisher, there is no way that the collar bomb caper was planned by Marjorie Diehl-Armstrong.

For facts, Fisher points to a profile of the FBI Behavioral Analysis Unit's Collar Bomber. "The [department's] view appears to be that this is much more than a mere bank robbery," it reads.

"The conduct seen in this crime was choreographed by 'Collarbomber' watching on the sidelines according to a written script in which he attempted to instruct others to do what he wanted them to do... The [FBI's Behavioral Analysis Unit] claims that because of the complicated nature of this crime, there were several motivations for the perpetrator, and money was not the primary one."

Whoever scheduled the heist didn't care if the cash was ever distributed by Wells. They just wanted to create a beguiling mystery, one that would defy explanation for years to come and keep cops and investigators searching for answers fruitlessly just as Wells was sent on his doomed search for scavengers.

None of this, Fisher claims, sounds much like Diehl-Armstrong, who credited prosecutors with arranging the whole affair to get enough cash to hire a hit man. But if this scheme wasn't put in motion by Diehl-Armstrong, who did it? "Fisher returns to the profile of the FBI, which notes that the bomb maker was" comfortable with a wide range of power tools and shop machines. "He was" a frugal person who saves scraps of various materials in order to reuse them in different projects. "And he was" the kind of person who is proud to create a variety of items.

That sounds like a definition to Fisher of Bill Rothstein, the man who lived next to the TV tower and who agreed to keep a dead man in his freezer in the garage. The handyman had the expertise to create such a sophisticated explosive device. The portrayal of the mastermind leading others according to a written script that only he seemed to have access to, was even more compelling to Fisher.

In Fisher 's opinion, from the beginning, Rothstein toyed with the investigators, concocted at least in part the scavenger hunt to send them on a futile pursuit, taking up valuable time in the precious days after the robbery. Then the 911 call came. Fingering Diehl-Armstrong allowed Rothstein to frame the Wells investigation on his own terms in the Roden murder case.

If he had not gone to the Feds, he realised it would be Diehl-Armstrong or one of his coconspirators. So before she could rat him out, he implicated Diehl-Armstrong in the Roden case, all while pleading ignorance of the collar bomb affair. He also gave the appearance of being a guy with nothing to hide. After all, why would someone involved in the plot call the cops on a voluntary basis and meet with them for hours? Rothstein continued to deny any knowledge on his deathbed of the collar bomb attack, even though he apparently had no more justification to hide. Rothstein was insulating himself before his death day, or "controlling the story," in Fisher 's words.

"The lawyer, Piccinini, characterised the crime as a" ludicrous, overwrought, overworked, desperately botched scheme "in his closing argument at the Diehl-Armstrong trial. If stealing money was the ultimate objective, then that's a fairly fair description. Fisher, however, thinks this wasn't about money. Rothstein, who never achieved much in life, wanted to show his genius by carrying out a crime that for years would attract headlines across the globe and baffle authorities. He hired coconspirators he felt he could manipulate and retained from them vital aspects of the plot, a strategy intended to further complicate the investigation.

Fisher says, "The son of a bitch ended up winning." "With all the secrets he died. He died with him taking all the answers. In that way, he gets the last laugh. He escaped punishment. He escaped detection. With these fools and a lot of questions, he left us."

Those questions, says Fisher, serve as a reminder of the ultimate victory of Rothstein. A free man has died. And the last step in the quest for scavengers, the clue that shows the answers that the agents have been looking for all along, will remain secret forever.

Hope you like the story share with your friends.

ThankYou!

About the Creator

Anshul Singh Tomar

I can define myself as a Design Thinker with a diversified portfolio of portals which includes Ecommerce Reviews, Job/Career, Recruitment, Real Estate, Education, Matrimony, Shopping, Travel, Email, Telecom, Finance and lots more.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.