The Psychotropication of the American Prisoner

Since the 1990 era of tough on crime laws, American defendants have been receiving psychotropic medications as a legal defense to avoid lengthy sentences.

How much time is too much? In the late 80s the U.S. Congress created a law recognizing crack cocaine, a derivative of powder cocaine, to carry a federal sentence 100 times the weight of its powder cocaine derivative. The Controlled Substances Act established a minimum mandatory sentence of five years for a first-time trafficking offense involving over five grams of crack, as opposed to 500 grams of powder cocaine. In other words, it enacted a criminal liability scheme that $125 of street value crack cocaine, is the moral and criminal equivalent of $12,500 of street value powder cocaine. A low bar entry of $125 to run afoul of federal law is targeting consumers, whereas a $12,500 price tag is targeting dealers. This criminal liability scheme created racial disparity in sentencing, as it was known at the time of its enactment, African Americans were the consumers of crack, while White Americans were the consumers of powder. The law imposed the same ratio for larger amounts: a minimum sentence of 10 years for amounts of crack over 50 grams ($12,500), versus 5 kilograms of cocaine ($125,000).

In November of 1995, Leandro Andrade, a nine-year Army veteran and father of three, stole five children's videotapes from a K-Mart in Ontario, California. Two weeks later, he stole four children's videotapes from a different K-Mart store in Montclair, California. Andrade was sentenced to two consecutive terms of 25 years to life in prison. A consecutive sentence means once he serves one 25 years to life, then he starts another 25 years to life. In 2000 Gary Ewing stole three golf clubs worth $400 each and received a sentence of 25 years to life. These two criminal acts were upheld by the United States Supreme Court as being valid sentences.

As a result of these late 20th century sentencing schemes, a floodgate in the use of the insanity defense arose. The insanity defense is a legal defense to the commission of a crime. As early as the 12th century, the use of an insanity defense has been a legal shield for a defendant found "not guilty by reason of insanity." This finding excuses a defendant from legal responsibility. This is true even though the person actually committed the crime.

While there's a desire to shield the mentally ill from the full brunt of the legal system, there are also concerns about false claims of mental illness used to manipulate the criminal justice system. Courts have struggled with developing a balance to protect the mentally ill, while protecting the public from those who would abuse the system.

In an August 2012 article in Slate, "Faking insanity: Forensic psychologists detect signs of malingering," the article recognizes that when someone commits a horrific crime, there is a public perception to wonder whether they are mentally ill? That was the speculation around Colorado shooter James Holmes. People wonder whether he's truly insane or building a case for an insanity defense, and this leads to the question: Can a criminal get away with faking insanity? In a state like Colorado, where proving insanity can avert a death sentence, the temptation to appear mentally ill must be strong.

Joe Simpson, PhD, MD, Supervising psychiatrist at the Los Angeles County DMH Jail Mental Health Services, authored the "Psychopharmacology in Jails: An Introduction," from The Carlat Psychiatry Report, May 2016, Correctional Psychiatry. In it, he relays how fast-paced the experience of jail psychiatry is. The initial intake interview is normally 30 minutes or less, and the distinction between authentic symptoms and malingering is rarely black and white. Common is medication-seeking. While many inmates are legitimately in need of psychiatric care, others are outright manufacturing psychiatric symptoms. They view the psychiatrist as a way to receive a diagnosis that will shield them from any future or pending punishment.

There is a high demand for psychiatric care in U.S. correctional facilities. At any given time, about 1% of the adult population is incarcerated, and many of them have a psychiatric disorder of some sort. One study used in Dr. Simpson's report found that 49% of jail inmates had symptoms of both mental illness and a comorbid substance abuse disorder. Other studies have found rates of severe mental disorders, including psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, and major depression, ranging from 10% to 27% of jail and prison inmates.

The report goes into the various kinds of medication administered in these pre-trial detention facilities, also known as county jails. Once convicted and sent to prison, these defendants who were doing the fake crazy to avoid lengthy sentences are now cycled through the state correctional mental health system.

Virtually every county has some type of jail facility, often located in large cities. Prisons, on the other hand, are usually remote from urban centers

---Dr. Simpson

Long prison sentences from failed attempts to be found guilty by reason of insanity, and the extreme isolation of prisons are factors that play negatively on the mental health of prisoners. The Vera Institute of Justice in an April 2021 report "The Impacts of Solitary Confinement" noted, “The widespread use of solitary does not achieve its intended purpose--it does not make prisons, jails, or the community safer, and may actually make them less safe.”

Prisons by their very nature make it very difficult for families to make these long and difficult treks to see their loved ones. A prisoner need not be in solitary confinement, because these isolated prisons are it's equivalent. Mass incarceration breeds mass releases, and is there any wonder why America has a serious, serious problem with homelessness. The rise in homelessness should have some attributions to the release of prisoners who were put on a carousel wheel of psychotropic medications from the county jail as pretrial detainees to the prisons where maintenance of these county jail medications are adhered to.

In 2018, Worth Rises, a non-profit advocacy organization dedicated to dismantling the prison industry and ending the exploitation of those it touches, held a Prison Art exhibition at the Urban Justice Center in downtown Manhattan, New York City, New York. The theme of the exhibition was Capitalizing on Justice. It featured the works of incarcerated artists from across the nation who used their talents to express the ways they and their loved ones have been commodified. It spanned a variety of genres and styles. The works were made using limited resources, such as state-issued materials, prison contraband, and yard scraps. They were shipped in makeshift envelopes and tattered boxes from as deep in the criminal legal system as Arkansas’ death row.

Incarcerated people know best that profits in the prison industry are directly linked to suffering. Often, however, words fall short in conveying the harms that commercialization inflicts.

---Worth Rises

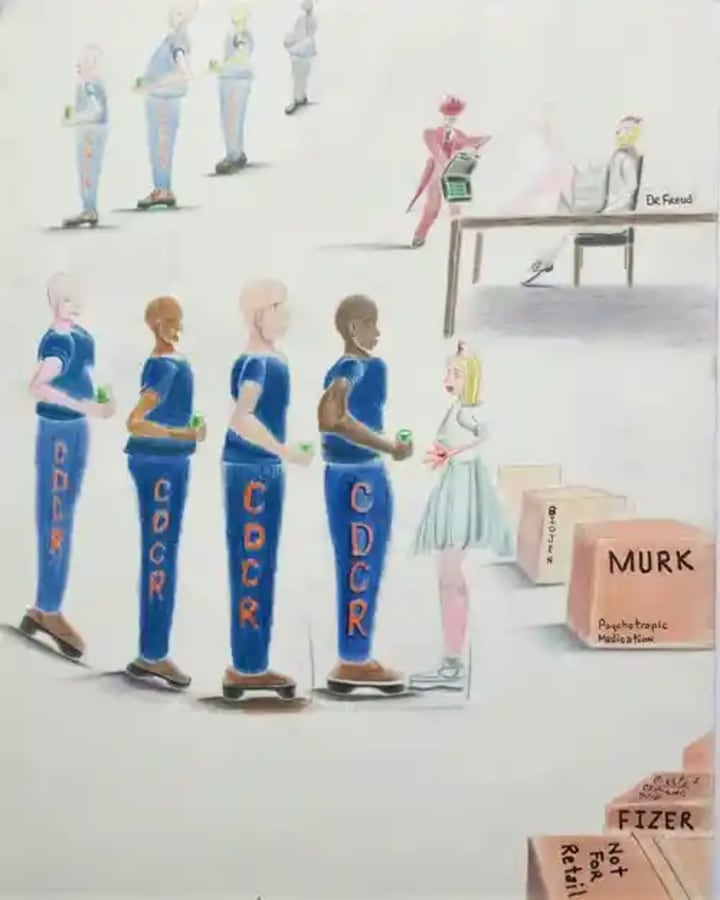

Artists who contributed to the exhibition received financial awards in compensation for their labor. One such contribution Capitalizing on Justice by American prisoner-artist Donald "C-Note" Hooker touches on the overuse of psychotropic medication on prisoners.

"This piece is part of my broader work on the existential threat of the widespread use of medication inside of America’s prison," says C-Note. "In the foreground, there are wholesale boxes, not for retail, of psychotropic medications from pharmaceutical giants like Merck (“Murk”), Pfizer (“Fizer”), and Biogen (“Biojen”). In the background, there is psychiatrist Dr. Freud harassing a nurse while being offered kickbacks from big pharma."

The exhibition Capitalizing on Justice has been shown at the Urban Justice Center and Gallatin Galleries at NYU in New York City, REVOLVE at SOUTH RAMP Studio in Asheville, NC, and the M.J. Freed Theater in Chester, PA. The exhibition's online gallery includes additional pieces not selected for the live exhibition. Contact Worth Rises to organize special group tours of the exhibition or to inquire about purchasing any of the art works.

Worth Rises — Capitalizing on Justicehttps://worthrises.org/capitalizingonjustice

About the Creator

Darealprisonart

A seller of Prison Art prints, and a publisher of the drawings, writings, sound recordings, and videos, by prisoners. We also publish news reports surrounding the politics of prison.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.