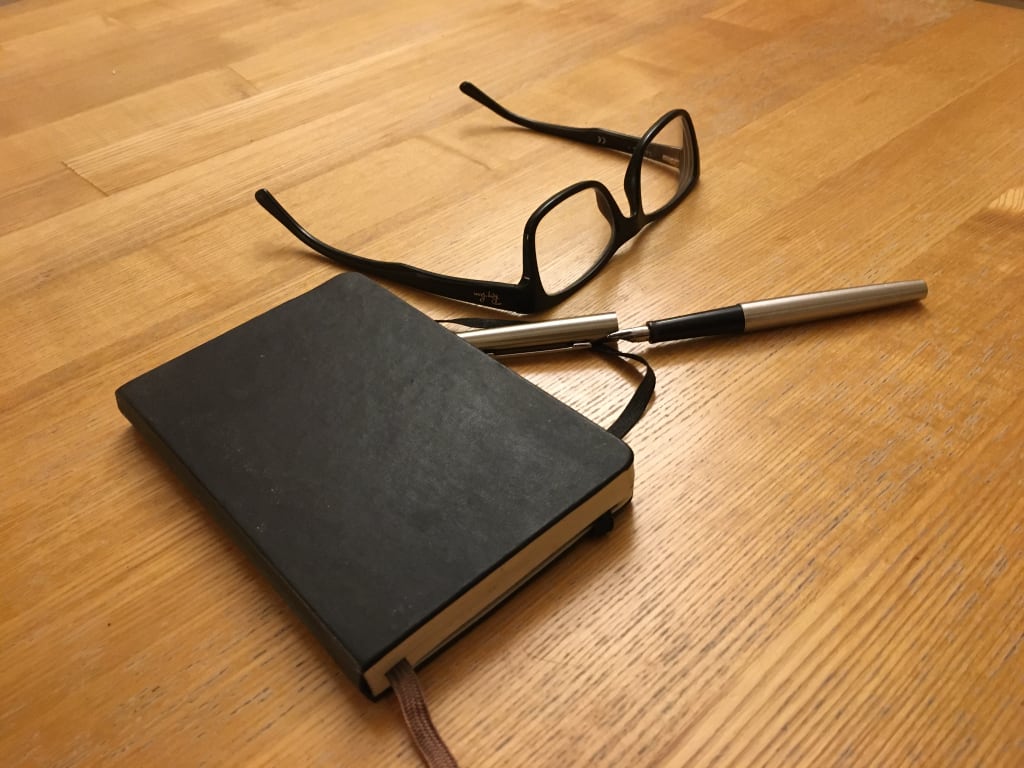

I kept it in a false drawer within my desk. An old, black Moleskine notebook that I’d been given many years earlier. At first, I used it to record events that I wanted to note, or memorable statements or quotes I wished to record and be able to refer back to. Sometimes when I was travelling, for work or on holiday, I’d write down times, places, even meals, that seemed worthy of inclusion in my little black book.

Whenever possible I’d use my old black Parker ink pen. A relic, these days, of a time long gone, when I and others would use now outdated pen and paper. If I didn’t have the pen to hand, I’d use a pencil or, reluctantly, a ballpoint.

The arrival of mobile phones and the growth of the internet rendered pen and paper obsolete in most circumstances. So much easier to take a photo, record a voice memo, or even type anything you wanted to record for posterity, although the ease of doing so led to a dramatic increase in the amount recorded, and a concomitant decrease in the value – even to the one doing the recording – of the material saved.

Then it became clear that, even if the photos and memos and words recorded and saved were relatively useless and worthless to the one who made them, they were far from useless or worthless to those who stored them for us.

It was then that the little black book (still complete with the little note about Van Gogh and Matisse, Hemingway and Bruce Chatwin in the pocket at the back) and the trusty ink pen, returned to use. Where to record the data that you wanted to ensure was never seen by anyone else? Where to note the events, people, times, places that were of great value to you, but which you would not wish anyone else to be aware of the existence of, still less the worth and potential benefit of?

I had once read of the mafia boss who, shunning mobile phones and almost all modern technology, was only caught when enough of the post-it notes he and his colleagues used to communicate were found and pieced together to form a case which enabled arrest, prosecution and conviction.

Though not in the same lines of activity as the mafia, the appeal of difficult to find and decipher data records was not lost on me, and so the little black notebook that had increasingly been left on a shelf gathering dust became an item of value again.

Activities of neighbours, colleagues, occasionally even family members began to find their way into the notebook. Activities that were innocuous enough in most ways, but activities that those engaged in them would prefer remained unknown to their own friends, families and employers. Dates, times, places and identities were again the bulk of what was recorded in my notebook, but now they were not simply of sentimental, personal value. They began to be worth much more. Used as the thinly veiled back-up to a quiet word in someone’s ear, this record came to benefit me in substantial financial ways. The existence of a hidden, written record of actions or materials that those involved would never want revealed to anyone else led them to wish to pay for that record to remain hidden.

It was fascinating to learn what seemingly trivial details or activities people would pay to keep from their loved ones, colleagues or employers: small purchases, clandestine meetings, ‘chance’ encounters, minor pilfering, unorthodox relationships, unusual habits… All had a secrecy value, and I was happy to be the one who took the value in return for the secrecy, while making it very clear that any harm to me would not result in the disappearance of the record.

Over time it became clear that the need for new information was less. The minor activities merited repeat payments for continued secrecy, and led to what was, in effect, a subscription service which, on top of my salary, left me in a very comfortable situation. I was not greedy, and made it clear to my clients that there would be no sudden demand for huge extra sums of money under threat of revelation.

As a result, one or two new pieces of information every few months – on existing or new clients - were sufficient to keep income on the increase.

At some point I realised that some extra security and back-up would be prudent and desirable, and as I considered the options the false drawer stuck me as an option. Utterly anachronistic in an age of data encryption with everything stored in an online cloud, it was an ideal solution. If you were searching for incriminating information that someone else held on you, you would surely assume that it was a laptop, or an external hard drive or ssd, that you needed to locate. A false drawer belonged in a Sherlock Holmes story, or a 1950s noir thriller.

Initially I wondered who I could find who I would trust to make it. Some of my clients lived in the same building and might notice a contractor. They might engage the same person for work of their own and start asking what they had done for me.

But the modern technology that I was using this to shun came to my rescue: all the information I needed to do it myself was available online, from descriptions of materials and tools required, to video manuals demonstrating precisely how to make and secure it.

It gave me a disproportionate sense of satisfaction to have completed the work myself, and once it was snugly fitted with its secret release contraption, I at first found it difficult to stop myself from continuing to open and close it.

The book stayed in the drawer much of the time, as the development in my business model meant that I was adding fewer new entries, and I needed to refer to it less as the regular cash payments came in without need for reminders.

Then one month one of my regular clients visited me. After she had made her regular payment, she made an announcement.

“I’m moving to another city,” she said. “I’ll be leaving in the next two weeks.”

“I see.”

She looked calmly at me for a few moments. I waited.

“Well?” she asked.

I shrugged my shoulders. “What do you mean?”

“What happens now?”

I waited.

She looked over her shoulder towards the door.

“I won’t be able to just pop round to make my…give you…this.” She picked up the envelope she had brought with her and replaced it on the table.

The implications then struck me. I thought for a moment. I didn’t want electronic payments directly into my bank account, but nor did cash in the post seem a sensible idea either.

I smiled at her. She looked nervous but did her best to smile back.

“Perhaps we can reach a compromise.”

She nodded.

“Perhaps a way to deal with this situation is for you to pop round one more time before you leave.” I reached for the envelope. “If what you bring is substantially larger than this one, we can consider it a final visit, after which you can consider your secret safe forever.”

She nodded again. “All right,” she said slowly. “And then…” she hesitated, “and then my name and details will all be removed from your records permanently?”

I nodded. “Of course.”

She smiled, this time more confidently.

“That would be…very satisfactory,” she said.

Over the following days I wondered what value she would put on the severance. I was not particularly concerned at what amount she would decide on, as my other revenue streams continued healthily, but I was curious. I tried to estimate what amount I would pay in such circumstances, what price I would put on final resolution.

The answer came a little over a week after that last visit.

I arrived home after work to find a small package just inside my front door. Initially wondering how it was inside the apartment, I concluded that one of my neighbours, who holds a key, had enabled whoever had delivered it to put it inside rather than leaving it at the doorstep.

My concerns about how it had arrived disappeared when I opened the package. Two large bundles of banknotes, all fifties: I would count them later, but I guessed it amounted to more than ten thousand dollars.

I laughed. It was more than I would have expected, but as I already mentioned I wasn’t sure what price I would put on such peace of mind, and it gave me a benchmark for any future transactions of the same type.

After I’d eaten dinner, I counted it. I counted it four times in total, as I was rather astonished at the amount. Each time, though, it came to the same sum: twenty thousand dollars.

I put the money in an envelope and packed it into my briefcase, ready to be banked the following day. Once the money was safely deposited, I could amend my little black book and, as promised, delete all details of that client.

I deposited the money at lunchtime, and made my home from work feeling very satisfied. As I approached my building, I was surprised to see her waiting outside.

I smiled at her, wondering if she had changed her mind and wanted to renegotiate the amount she had paid.

“Won’t you come on up?” I asked.

She nodded and followed me upstairs.

Once inside, I asked her to sit.

“How can I help?”

“Well, as we discussed last week, I’ve come to make my final payment, so we can…you know…”

I nodded, now puzzled about the twenty thousand dollars.

She reached into her purse, and drew out an envelope, which she placed on the table between us.

“I don’t know if you want to count it now, or…”

“No, no. I’m sure it’s quite adequate.”

“I hope it’s enough. If it isn’t, then I guess we’ll have to think again.”

“I’m sure that won’t be necessary,” I replied, smiling.

She left, and I sat down, confused.

I picked up the envelope she had left. Inside it I found two and a half thousand dollars.

Perplexed, I went to the dresser, and opened the drawer with the false bottom. Perhaps I had misremembered why she was in my book and overestimated what she would be willing to pay.

I took out the book, and as I opened it, I realised. An identical Moleskine notebook to mine even, as I later discovered, with the same back page pocket and the note about Van Gogh and Matisse.

On the first page I found, neatly recorded in black fountain pen ink, an entry detailing the first payment I had received. The date, the amount, the reason for payment but, crucially, not the name of the client. As I flipped through the book, I could see that it detailed every single transaction I had made. It was chilling to realise that I had been under such comprehensive surveillance. I wondered who it could be, and why.

I flipped through the notebook and found the last entry for the client who had just left. It was for the amount she had brought the previous week, not what she had just delivered.

Underneath it, a final entry: Moleskine notebook - $20,000. Account closed.

On the facing page, a Post-it note. “We’ve bought you out of your business. Any attempt by you to continue will result in publication of the contents of the envelope you’ll find in your mailbox now.”

I walked, terrified, to the mailbox, wondering what could possibly be waiting there.

I opened it, glancing over my shoulder as I did so.

When I saw what was in the envelope, I shuddered as I learned what being one of my clients had been like and felt the helpless horror of being at the mercy of another.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.