On Jan. 17, 1973, Ginsburg skipped lunch because she was afraid she would vomit. In the afternoon, wearing the brooch and earrings her mother had left her, like a soldier in armor about to go to war, she stood before nine stony-faced Supreme Court justices and asked them to recognize that the U.S. Constitution forbade discrimination on the grounds of sex. Until that day, the Supreme Court had refused to recognize it.

All court arguments on the Supreme Court begin with the same sentence: "Mr. Chief Justice, and distinguished Justices." On the recording, Ginsburg's voice trembled a little as she said this. It was her first time arguing before the Supreme Court.

Ginsburg took the opening line to heart, but her stomach turned with nervousness. After trying to compose herself, Ginsburg told the justices that the government had denied Joseph, the husband of Air Force Lieutenant Sharon Frontiello, the housing and medical benefits to which an officer's spouse was entitled, simply because Lieutenant Sharon was a woman.

Fourteen months ago, the Supreme Court, in Reid v. Reid, ruled that Idaho could not rule that a mother was not entitled to a deceased child's estate on the basis of sex alone, because men were not necessarily more competent than women. But in Reed, the Court did not definitively answer a more important question: whether most discrimination based on sex is unconstitutional. Ginsburg took a deep breath and asked the justices to answer that question definitively in Frontiello.

Ginsburg pointed out that both the state law in Reed and the federal law in Frontiello v. Richardson are based on "the same gender stereotype that men are independent individuals in a marriage relationship, while women are, for the most part, subservient to men and are not responsible for supporting their families."

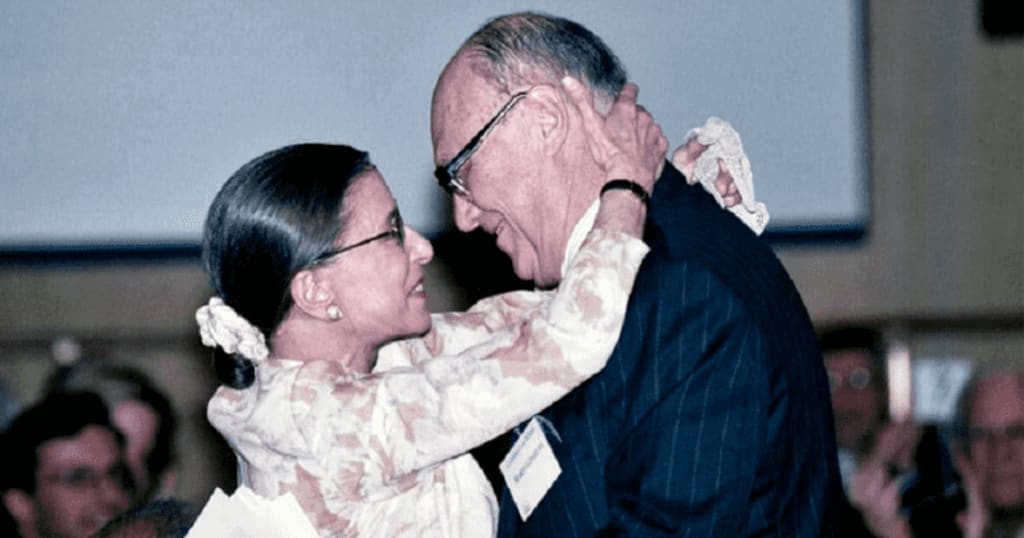

Ginsburg usually looks for Martin in the audience when she speaks in public, but this time he had to sit behind her in the Supreme Court. He sits in an area reserved for lawyers allowed to appear before the Supreme Court.

Knowing where Martin was sitting, Ginsberg felt assured. She has ten minutes to argue her case before nine of the most powerful judges in the country. Ginsburg knows more about the facts of the case and the law than the justices, and her task now is to teach them. Ginsburg knows what to do. After all, she has been a law professor for nearly a decade.

On the Supreme Court bar license card she received that day, Ginsburg was identified as "Mrs. Ruth Bader Ginsburg." Ginsburg has demanded that she be called Ms. Ginsburg ever since the term "Ms." appeared. On this day, a number of Ginsburg law students came to see her in court, and after hearing her referred to as "Mrs.", they winked and told her to ask the court to change "Mrs." to "Ms.". Ginsburg declined. Her purpose today was to win the case, not to waste energy on details that did not require immediate resolution.

Ginsberg's argument is radical. The nine men who sit on the Supreme Court bench consider themselves good husbands and fathers, but they believe that men and women are fundamentally different, and that women are lucky to be protected from the pressures and tricks of the real world. But Ginsburg, a woman in her late 40s, wants to convince the justices that women deserve the same place in the world as men.

Ginsburg told the justices that the law's differential treatment of men and women not only implies "a value judgment that women are inferior to men," but also blatantly tells women that even if they do the same work as men, their work output and family are less important than their male colleagues. "These distinctions all have one consequence," Ginsburg said firmly. "They make women inferior in society and force them to settle for the status quo."

Brenda Fagan, who co-founded the AcLU's Women's Rights Project with Ginsburg a year ago, sat behind Her, cases spread out on the table in front of her, ready to give Ginsburg the case citations she needed. But Ginsburg didn't need it. She was as familiar with her own phone number as she was with precise citations of relevant precedents.

Ginsburg's opponent that day was the federal government, which in its brief defended its policy of implicitly subordinating women to men and thus allowing men to claim dependant support only in very specific circumstances. After all, most breadwinners are men. The name on the cover of the federal brief is Owen Griswold, ginsburg's dean at Harvard Law School. Ginsburg is a far cry from when she told Griswold, against her will, that she went to law school just to be a good wife to gossip with her husband.

The justices remained silent. Ginsburg continued: "Gender, like race, is an obvious but hard-to-change personal trait that has nothing to do with competence." The gender and racial analogy in the context of the constitution of the United States has a special meaning: after "brown v board of education" in a series of cases, the Supreme Court confirmed a principle, namely according to the law of different racial discrimination in violation of the constitution, in principle, all need at least through the "strict scrutiny" to determine whether the government has a significant and the exact reason for discrimination. In Reed, the Supreme Court concluded that the strict review standard did not apply to laws that discriminate on the basis of sex, but it appears to have been used in reaching the practical rationale for the final decision. The question in this case is whether, in principle, a law discriminating on the basis of sex is unconstitutional as is a law discriminating on the basis of race? Ginsburg boldly asked the court to say yes.

Toward the end of her 10-minute speech, Ginsburg looked the justices in the eye and quoted abolitionist and suffrage advocate Sarah Grimkay. "Her language was not beautiful, but it was very clear," Ginsburg said. "She said, 'I never ask for special treatment because of my gender. The only thing I ask of my fellow men is basic respect. '" Often, the lawyers sitting before the Supreme Court are interrupted repeatedly by the justices, sometimes without even getting a chance to finish a sentence. But a hungry Ginsburg spoke in court today with a faint Brooklyn accent without a single interruption. Her speech left the justices speechless with shock.

Ginsburg was outwardly calm, but inside she was beating a drum. Did the justices really listen to her? She won't know the verdict for five months. After the trial, the crowd streamed out, and dean Griswold, a burly figure, joined Ginsburg. He had just watched his own lawyers exchange words with Ginsburg and her co-counsel. Griswold grimly shook Ginsburg's hand. That night, Justice Harry Blackmun gave Ginsburg a C+ in his journal, as usual, when he graded the lawyers who appeared that day. "This is a very serious woman." Blackmun wrote.

Land, like women, is destined to be possessed

A decade earlier, in 1963, Ginsburg was less active in advancing women's rights. Although she was struck by Simone de Beauvoir's book "The Second Sex" in Sweden, she shelved everything she learned there except for civil procedure law. At the time, Ginsburg had just started teaching at Columbia Law School. One day, her colleagues told her that Rutgers law school was looking for female professors because the school's only black professor had left. There were no women or black full professors at Columbia Law school at the time, but no one seemed to care. Rutgers law School has one of only 14 tenure-track female faculty members in all law schools in the country. Soon after Ginsburg accepted a teaching position at Rutgers Law School, the Newark Star-Ledger published a story about her and another female professor, Eva Hanks. The story called Ginsburg and Hanks "ladies in robes" in the headline, and opened by describing them as "slim and attractive" and exaggerating that "they were so young that they could easily have been mistaken for students."

Rutgers would only sign Ginsburg on a one-year contract to teach civil procedure law at a low salary. After all, Law school dean Willard Heckel reminded Ginsburg that Rutgers was a public school and that she was a woman. "They told me, 'We can't pay you as much as Professor A, because he has five kids and your husband makes a good salary,'" Ginsberg recalled, carefully withholding Professor A's real name. "I asked, 'Does professor B, who is single, make more than me?'" When she got the positive answer, Ginsburg stopped asking and turned to hard work. She commuted by train from Newark to Manhattan, New York, and published articles with titles like "Recognition and Enforcement of International Civil and Arbitral Awards." She made it through the first year.

Soon, however, an unexpected event upsets the Ginsbergs' peaceful life. Years ago, while Ginsburg and Martin were in law school, Martin had surgery to treat testicular cancer. After the surgery, doctors told them that Martin's radiation treatment was their last chance to try for a second child. At the time, Ginsburg, struggling with the weight of law school work, caring for her young daughter and anxiety over Whether Martin would survive, could not imagine having another child. In 1965, just as the Ginsbergs were on the verge of convincing Jane, who was about to turn 10, that having only one child in her family was not such a bad thing, Ginsberg found out she was pregnant. "Tell me, honey," the doctor asked, holding Ginsburg's hand, "do you have another man?" Ginsberg did not cheat. Martin underwent tests that confirmed his ability to produce sperm even after radiation treatment.

Ginsburg's joy at being pregnant was mixed with anxiety about whether she would keep her rutgers faculty position. Rutgers will decide at the end of the spring semester whether to give her an employment contract for another year, and Ginsburg has no plans to repeat the pregnancy that laid her off at the Social Security Administration in Oklahoma. She was due in September and had borrowed larger clothes from her mother-in-law, Evelyn Ginsberg, to hide her bump, hoping the school would not find out she was pregnant before summer vacation. It worked. Ginsburg took the last class of the spring semester and secured a second-year employment contract. That's when she told her colleagues she was pregnant. On September 8th the Ginsbergs' second child, James, was born. Shortly after, Ginsburg returned to her post as if nothing had happened.

But ginsburg's environment began to change. One of her students declared himself a member of the free speech movement. "Every day before class, he would sit down on a high spot and occasionally make contemptuous gestures to me." "Ginsberg recalled. When she started teaching at Rutgers, there were maybe five or six women in each class. But as more men were sent to fight in Vietnam, the number of women slowly began to increase. Outside the classroom, "The Feminine Mystique," about educated middle-class women unhappy with their trapped roles in the home, sold more than a million copies in its first printing. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, meanwhile, banned workplace discrimination as well as racial discrimination, and the congressmen who passed it made a lot of henpecked jokes. (Councilman Emanuel Selle jokes that he usually has the final say in the house: "Yes, dear." )

The New Jersey chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, where Ginsburg volunteered as a lawyer, received a flood of letters from women after the bill passed. Ginsburg was assigned to handle the letters as a woman. She dutifully read all the letters. The letter said Lipton Black Tea wouldn't allow female employees to add family members to their health insurance because the company assumed that only married men would have dependents; Princeton's engineering summer camp excludes women; The best tennis players in Teaneck, New Jersey, were not allowed to play varsity sports because they were women. Other letters brought back embarrassing memories for Ginsburg. Women teachers wrote that they were forced to leave their jobs if they showed signs of pregnancy, sometimes even before. Schools call it "maternity leave," but it is neither voluntary nor unpaid, and it depends on the mood of the school whether they can return to class after giving birth. One woman was given an honorary discharge after becoming pregnant, but when she tried to re-enlist she was told that pregnancy was a "moral and administrative disqualification". These problems are not new. But it is new that people are starting to complain about these things. Ginsburg, at least, had never thought to complain before.

Most of the women in law school were about a decade younger than Ginsburg. They are no longer content with verbal protest, but have made clear demands. Some of them came from Mississippi to advance the civil rights movement in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee [2]. These young women, who had witnessed lawyers pushing for equal rights, arrived at law school only to find a culture that still expected girls to behave. At the same time, universities were under pressure to gradually increase their female representation, especially after President Lyndon Johnson's federal administration in 1968 made gender discrimination one of the "crimes" that reduced federal funding.

Ginsberg looked on admiringly at the girls, who were so different from the women of her own generation. In Ginsberg's day, women were afraid to ask for anything for fear of drawing too much attention. In 1970, at the request of her students, Ginsburg taught the first law course on women in rutgers law school history. It took Ginsburg only about a month to read all the federal precedents and legal journal articles on women's legal status, because there wasn't much discussion. Indeed, a famous textbook says, "Land, like women, is destined to be possessed." (This is a book that discusses land ownership, and women are used only as metaphors for understanding.) After reading the material, Ginsburg made a secret decision: She would no longer suffer in silence the injustices of being a woman, including the "lady discount" on her pay. Ginsburg, along with other female professors, has filed a federal class-action lawsuit accusing universities of discriminating against women in pay. They won.

On August 20, 1971, lainey Kaplan, a mail carrier from Springfield, New Jersey, wrote to the New Jersey branch of the American Civil Liberties Union to complain that the post office would not allow her to wear a mail cap worn by male mail carriers. "A mailwoman's hat is a beret or bonnet with no brim, so my badge can't be pinned to it," Lainey explained. "Also, the brim of a mailman's hat can keep the sun out of your eyes, but not a mailwoman's."

At the time, Ginsburg was preparing to spend a semester as a visiting professor at Harvard Law School, and she had successfully brought cases to the Supreme Court. But for her, no sex discrimination case is irrelevant. "It is arbitrary to discriminate between male and female postmen by hat style at the expense of functional features that enhance job performance." Ginsburg wrote in a letter to the postmaster General. The director may not have known what he was up against.

Ginsburg was well aware that writing fiery letters to fight sexism was just a drop in the bucket. If this problem is not addressed fundamentally, there will always be more sexist laws. Feminist activists should see the big picture. What America needs, whether in the small matter of mail caps or federal policy, is a broader acceptance of gender equality. For decades, some feminists argued that the ultimate solution to gender equality was to add an Affirmative action Amendment to the Constitution: "The federal and state governments of the United States shall not prejudice the principle of equal rights in the laws on the basis of sex."

The amendment, abbreviated ERA, has been proposed in every session of Congress since 1923, but has never been passed. Ginsburg thinks this may be because the current constitution already provides a solution to achieving gender equality. After all, the first sentence of the constitution's preamble begins with "We the people," and women are part of the people. Don't women deserve the equal protection promised under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, even though they have been subject to restrictions for a long time in history? The question is how ginsburg can get at least five justices on the court to agree with her interpretation of the Constitution. In the early 1970s, when the role of women in society had fundamentally changed, the Supreme Court was still stuck in its old ways. Perhaps, if a proper case could be brought to the Supreme Court, the justices would change their minds.

One evening, Ginsburg was working in her bedroom as usual, pondering her legal strategy. "There's a case you must read about." Martin, who was working in the dining-room as usual, exclaimed suddenly. "I don't read tax cases." Ginsburg responded. But she was glad she read the case later.

Charles Moritz is a traveling salesman who lives in Denver with his 89-year-old mother. Every time he travels, Moritz needs to hire someone to care for his elderly mother, but he has trouble claiming those expenses to claim a tax deduction. The IRS only allows women, widowers or men with incapacitant wives to claim a tax deduction for family care expenses, but Moritz has never been married. Apparently, the government has never considered the possibility that men may be required to take care of family members on their own. After reading the case, Ginsburg grinned broadly and told Martin, "We'll take the case." It was her first professional collaboration with Martin.

On the face of it, the Moritz case is unremarkable. Moritz hired someone to care for his mother for a mere $600. Nor does it seem to have much to do with injustice to women. But Martin and Ginsberg have bigger plans. In their view, there is no justification for denying government benefits to citizens of one sex or another based solely on their sex. If the court decides that the policy is wrong, the case could serve as a precedent for broader recognition of gender equality.

Ginsburg wrote to MEL Wolfe, an old friend from summer camp when she was a teenager, asking for support. Wolf, who is now national legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union, decided to support the Ginsbergs in their lawsuit. Wolff later told the writer Fred Szczerbaugh that he knew Ginsburg was doing "low-level women's rights work" in New Jersey, and bragged to Szczerbaugh that he was going to bring Ginsburg "out of obscurity." He's gonna take her to the Supreme Court.

The Ginsbergs argued in their brief that the government could not discriminate between men and women "when their biological differences are not relevant to the matter in question." Ginsburg sent her written brief to Wolff. She knew that the American Civil Liberties Union had taken up reed v. Reed's case before the Supreme Court. In Reid v. Reid, Idaho law gave men priority over women over inheritance. In the case, Sally Reed's husband, Cecil Reed, beat her and then left his wife and son, but when their son committed suicide, Idaho law gave Him the right to dispose of the small inheritance because he was a man. If Moritz and Reed were brought to the Supreme Court in a single case, Ginsburg said, it would be possible to convince the justices that gender discrimination hurts everyone.

"There should be something in the material that would benefit Reid v. Reid." "Ginsburg wrote to Wolff on April 6, 1971, in a brief she had written for the Moritz case." Have you considered that the case might benefit from having a female co-counsel?" Ginsburg has rarely asked for special consideration because of her gender, but she felt it was worth it if it got her to the Supreme Court. Years later, Wolff told Szabel, "Well, maybe I didn't bring Ginsberg out of obscurity. Perhaps it was she who brought her out of obscurity. He was right. Wolff told Ginsburg that he really needed her help in taking Sally Reed's case to the Supreme Court.

The stakes in taking Reid to the Supreme Court are enormous. If the Supreme Court is not ready to overturn precedents that treat women as second-class citizens, Reed may take the court further down that wrong path. Just a decade earlier, in 1961, a woman named Gwendolyn Hoyt had been convicted of murdering her husband by an all-male jury, and she questioned its composition. In Florida, male citizens are required to perform jury duty, while women are required to choose to serve on juries. The Supreme Court justices said it did not matter whether women participated in civic activities because, after all, women were "still considered the center of family life." Hoyt showed that the Supreme Court's approach to gender issues had not improved since 1948. In 1948, Justice Felix Frankfort -- the same Supreme Court justice who refused to hire Justice Ginsburg -- lamented in an opinion that allowing women to work as bartenders could "lead to moral lapses and social problems."

While in law school, Ginsburg spent a summer working at the Law firm Of Bowers, where she met a black female lawyer named Pauli Murray. Racial and gender equality were generally considered separate issues in the civil rights movement at the time. But Murray was passionate about building Bridges between parts of the civil rights movement, which she believed was too dominated by men and which feminists were often ill-informed about racial issues. While Ginsburg was the one who moved the court in a new direction, Murray was the first to pioneer that path.

As early as 1961, Murray theorized that the Equal protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution alone was sufficient to provide a legal basis for women's emancipation. Murray and dorothy Kenes, a colleague at the American Civil Liberties Union, are trying to find a way to overturn Hoyt. In 1965, Murray co-authored a comparison of racial and gender oppression, "Women Oppressed by Discrimination and the Law," that Ginsburg, then teaching at Rutgers Law School, included in her syllabus. The paper argues that issues of race and gender are separate but related. A year after the paper was published, Murray and Kanis wanted to put the theory into practice. So they challenged a verdict in Alabama in which an all-white, male jury found the men not guilty of killing two suffrage activists. They won the case, but it never made it to the Supreme Court because the losing state of Alabama decided not to appeal.

Ginsburg's soon-to-be-famous Reade brief is full of traces of Murray's theory, and includes rare quotes from Simone de Beauvoir, the poet Alfred Lord Tennyson, and the sociologist Gunnar Myrdahl. Students in Ginsburg's feminist law class also helped write the brief. The brief notes that the world's attitudes to women have changed, but the law has stagnated. Before filing her brief to the Supreme Court, Ginsburg wrote "Dorothy Kanis" and "Pauli Murray" in the author column of the title page. Ginsburg later said she wanted it to be clear that she was "standing on their shoulders."

"You shouldn't have done that." Burt Newburn, ginsburg's colleague at the American Civil Liberties Union at the time, remembers telling her. Newburn said the names were "against the rules."

"I don't care," Ginsburg replied. "They deserve to be." Later, Ginsburg said she had simply continued where Kanis and Murray had left off. Fortunately for her, the world was finally ready to listen.

Early letters sent out by the American Civil Liberties Union's Women's Rights Project had an unusual stamp design that featured a Playboy bunny. At least one recipient of such a letter expressed outrage. But that's only because Playboy magazine is a big sponsor of the American Civil Liberties Union, and these stamps are its gift to women's rights projects. The women's rights division of the American Civil Liberties Union started out poor. Its first full-time employee was Brenda Fagan, a Harvard Law school graduate who became a feminist. From time to time, Ginsberg's students do some of her legwork.

Despite limited funding and staff, Ginsberg has big ambitions for the project. After winning Reed, Ginsburg presented her plans for the women's rights program to the American Civil Liberties Union. In addition to Hugh Hefner, the founder of Playboy magazine, Owen Griswold is an unlikely unofficial sponsor of women's rights projects. After the Ginsbergs won moritz in the tenth Circuit, Griswold, who became solicitor General, protested to the Supreme Court that it must overturn the tenth Circuit's decision or hundreds of federal laws would be found unconstitutional. To prove her point, Griswold attached Annex V to her brief, which included the existing laws that discriminate between men and women. Ginsburg immediately recognized the attachment for what it was: a list of laws she would overturn.

Laws were in place to ban discrimination in pay, employment and education, but Ginsburg's promise on paper was shaky. "In the context of gender discrimination in society, culture and law, it has been a long road for women to get equal rights." Ginsburg wrote in a prospectus in October 1972. The ACLU's women's rights project has three main missions: educating the public, changing laws, and prosecuting women's rights cases with the help of acLU chapters.

Fighting for equal rights for women means questioning everything. Despite the Supreme Court's decision to legalize abortion in the face of social pressure, "further questions should be raised about the excessive restrictions on access to abortion and the medical benefits available during abortion." Other priorities of the women's rights project, Ginsburg writes, include "the right to choose sterilization" -- doctors often advise middle-class white women not to be sterilized -- "and the right not to be forcibly sterilized," as women of color and women deemed "mentally unfit" often are. The program, Ginsburg wrote, would call into question discrimination in education and training programs; restrictions on women in mortgages, credit cards, loans and home rentals; discrimination against women in prison or the military; and the incarceration of young girls in juvenile detention "for being sexually active." The project will also challenge institutions that discriminate against pregnant women.

On May 14, 1973, the Supreme Court decided Frontiello v. Richardson, the first case in which Ginsburg appeared independently before the Supreme Court. In theory, Ginsburg won another victory: the Court struck down a rule that said Sharon Frontiello's work was less important to her family than a man's was to his. Justice William Brennan wrote a decision that sounded like a victory for women's rights. "Traditionally, such discrimination has been justified as' romantic patriarchy ', but in reality it is not about putting women on a pedestal, it is about locking them up in a cage full of restrictions." Justice Brennan wrote that those were the exact words of women's lawyers. But in that case, Ginsburg still failed to get the five justices to agree on the broader principle that most laws that discriminate on the basis of sex are unconstitutional. Justice William Rehnquist was the only dissenting justice in the case. "My wife accepted long ago that she was married to a male chauvinist pig, and my daughters have no interest in anything I do," he told the La Times.

But in this case, Ginsburg learned a lesson that will stay with her for the rest of her life. She has been trying to civilise her fellow justices, and she is not about to give up. But she later admitted: "You can't accept an idea all at once. I believe that social change needs to be cumulative and gradual. Real, sustainable change takes place one step at a time." She must remain patient. She has to plan her strategy. And she occasionally had to play dumb.

When ginsberg's fellow feminists were often on fire to change the world at once, she persuaded them to see things her way. "She insisted that we change the law step-by-step, step-by-step," Kathrin Paratis, a colleague of Ginsburg's at the American Civil Liberties Union, later said. "' Only bring the next logical case to the Supreme Court, 'Ginsburg always reminded us, and then the next, and then the next. 'Don't push too hard, or you may lose the case you should win. 'She used to say,' This case isn't ripe yet. 'We generally listened to her, and we lost every time we didn't."

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.