What I learned from the murder of Phil Masterson

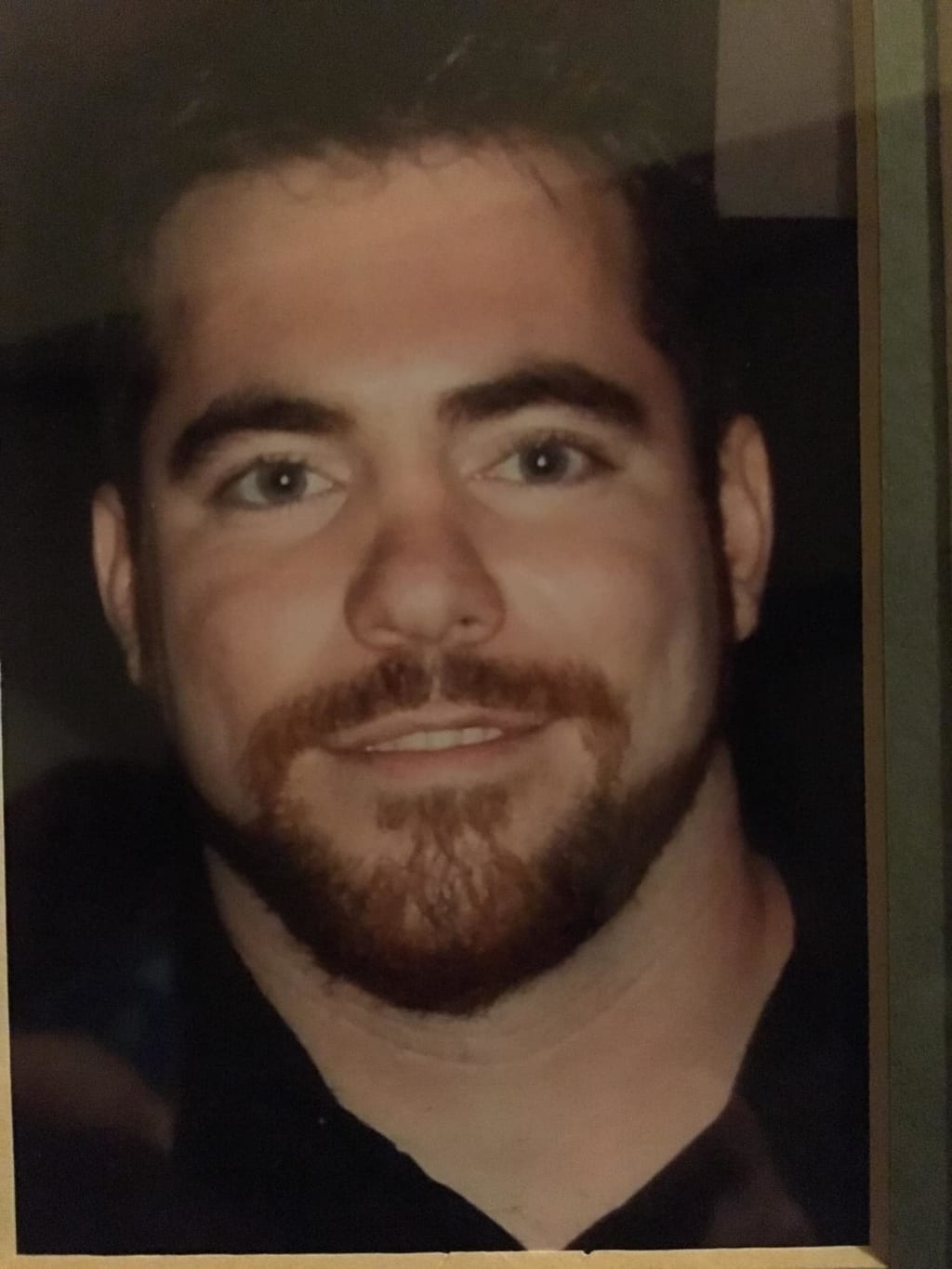

In 2011, my friend was found dead in the woods, covered in a grill tarp and missing most of his clothes. But what happened to him is no mystery.

I’ll never forget the phone call I answered, mid-morning on a weekday, in the fall of 2011. It was the day after Labor Day, and I’d spent the weekend trying to ignore my looming sense of dread. I blamed my pregnant brain—I was eight months along—and got back to the daily grind. Until I got the call.

“There’s an article in the Plain Dealer this morning—Phil Masterson? Weren’t you friends with him?”

I remember hearing a sudden burst of static, the kind that happens in old-school horror movies before the killer cuts the victim’s phone line. Looking back, I know that was probably my imagination. But the next words I heard were not.

“He was killed on Put-in-Bay this weekend.”

What do you mean, killed? How? By a drunk driver? I hung up the phone and found out I was late to the media circus—everyone else had found out two days earlier, when I was still at a cabin in Northern Michigan with virtually no cell phone service. Phil Masterson was killed in a “senseless beating,” and a suspect, Zachary Brody, had already been named. Since I was the last to know, I silently promised I’d also be the last to forget.

And I didn't forget, not for a day. I did, however, keep my feelings private for many years. I was married and raising a baby. I was supposed to mutter "what a tragedy" and move on, at least publicly.

But it was that word that stuck in my head: senseless.

That was the word I kept hearing, ad nauseum, to describe Phil's killing.

Phil Masterson's lifeless body was discovered in a wooded area on Put-in-Bay Island in Lake Erie, a popular long-weekend destination for Ohioans like us. Phil was found wrapped in a grill tarp and missing his clothes, save for a pair of mesh shorts. He had been savagely beaten, his body covered in bruises. The judge would eventually call it "the worst beating" he had ever seen "inflicted without a weapon." But an autopsy found that Phil had actually survived the initial assault. The official cause of death was strangulation.

I already knew something was not right. Strangulation is rarely an accident; it's not "senseless." I also knew immediately that Phil must have been physically subdued, possibly bound with restraints on his ankles, wrists, or both. Either that, or Brody had help. I come from the same line of "barrel-chested" Irish boxers as Phil, where the men are frequently described as "workhorses" who are "built like an ox." True to his birth sign, Taurus, Phil was a bull. There was no way he had been beaten so viciously and then choked by only one person. Brody himself admitted he was with a large group of friends that weekend, all staying in cabins 90 and 92 of Put-in-Bay's Island Club.

So why was only one arrested?

Starting the day Phil's brother, Mark, found him wrapped in tarp behind rental cabins, the storyline remained unchanged. It was the story of two men, Phil Masterson and Zach Brody, who liked to fight. In fact, via MMA (Mixed Martial Arts), they planned to make it their livelihood. They engaged willingly, fueled by too much beer and too much testosterone. Sadly, one ended up dead.

It helped explain why only one person, Zach Brody, faced criminal charges. It was why he was sentenced to 16 years, an incredibly light punishment for a convicted murderer. It was tragic, it was “senseless,” and it was what we all knew—and it was wrong.

Phil’s story faded from local headlines in our hometown of Cleveland after Brody’s conviction. But it has never been over for the Masterson family: Phil’s parents, Kevin and Georgeanne, his sister Molly, and his brothers Mark, Matt, and Jimmy. Jimmy Masterson never recovered from Phil’s murder, and he, too, died in 2018, at age 29.

Jimmy’s death was truly senseless—an accident. Phil’s death, on the other hand, was not “senseless.” The people involved thought rationally, every step of the way. They covered their tracks, concocting clever legal defenses as they drove off the island. For days, they dodged authorities. They played hide-and-seek with the police and refused to talk. They did it even as the Mastersons searched the island for Phil's body, hoping he was still alive but knowing deep down that he was dead.

Thanks to the work of Phil’s brother Mark, now a Cleveland attorney and the trustee of Phil’s estate, alongside attorneys Patrick Farrell and John Forestal, two more people have finally been held accountable. This autumn, a jury ruled that two of Brody’s friends, Cameron Parris and Clifton Knoth, were also responsible for Phil’s death. Judge John O'Donnell ordered them to pay roughly $23 million in damages. The jury found no negligence on Phil's part.

Mark says his family will probably “never see a dime” of the money awarded. But, as Phil’s mother Georgeanne tells me, it’s never been about money. “It’s about the truth,” she says.

So what is the truth? Why did the media report that Phil had died in a two-to-tango situation? And why did some outlets call him "a drunken provoker"?

Because the witnesses lied. Brody’s accomplices, including his girlfriend, Sarah Partlo—who later served six months in jail—knew Phil was dying. They knew that Brody dragged Phil deeper into the woods while he was still conscious. Brody returned to Put-in-Bay with Partlo to wrap the body in tarp later that day.

Phil was probably still alive. Not one witness called 911.

I believe these two--and possibly others--planned to dump Phil's body in Lake Erie. Mark Masterson agrees. He also agreed that someone disposed of Phil’s clothing to destroy DNA evidence. Phil’s friends remembered exactly what he wore that night — a Cavs shirt, jeans, and obviously, shoes. None of these items were ever recovered. Mark Masterson found Phil’s undershirt strewn in the woods, which eventually led him to his brother’s body. Phil’s wallet was thrown into a trash can. His license and the contents of his wallet were taken, and some were dispensed at the murder scene. His license was taken by Brody back to the mainland.

Initial reports claimed that Phil had arrived at Brody’s cabin in a rage, pounding on the door and ready to fight. I was shocked to learn this was a complete falsehood on the part of Brody and his friends. Phil was there because he was invited. A mutual friend, who knew both Phil and Zach Brody, invited Phil to “help drink the beer” they’d brought to Put-in-Bay so they wouldn’t have to lug it home the next morning. Phil went. From there, the stories start diverging. This is where things stop adding up.

Under pressure, Brody’s friends began accusing each other. They described watching “someone” wash Phil's blood off the deck. If they got too close to admitting the truth, they would backtrack and demand an attorney. They replied to questions by saying, "I do not recall." Georgeanne Masterson says the worst part of the trial was watching witness after witness say “I do not recall” with a smirk on his face. It was clear they did remember the details of the murder. But whatever they knew, they weren’t telling. The family’s last option for justice was a lawsuit in civil court. The Mastersons already anticipate that the men found liable for Phil’s death will find clever ways to dodge paying the damages.

As a fellow Millennial, I will grant these people one thing. In many ways, they are smart. It's obvious that they watch a lot of crime shows. They know how to feign confusion and fear, even righteous indignation at being accused. They claimed Phil made them "afraid" for their own safety—even though there was one of him and a half-dozen of them. They knew how to lawyer up and shut up. They are experts at looking out for Number One.

They're smart, but they have no conscience. No morals. We should shudder at the fact that some of them are now raising children.

We hear enough about the failures of Millenials and Gen Z youths. Maybe it’s time for Cleveland’s Baby Boomers to ask themselves and each other: What kind of kids did we raise?

About the Creator

Ashley Herzog

If you like my work, feel free to tip your writer.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.