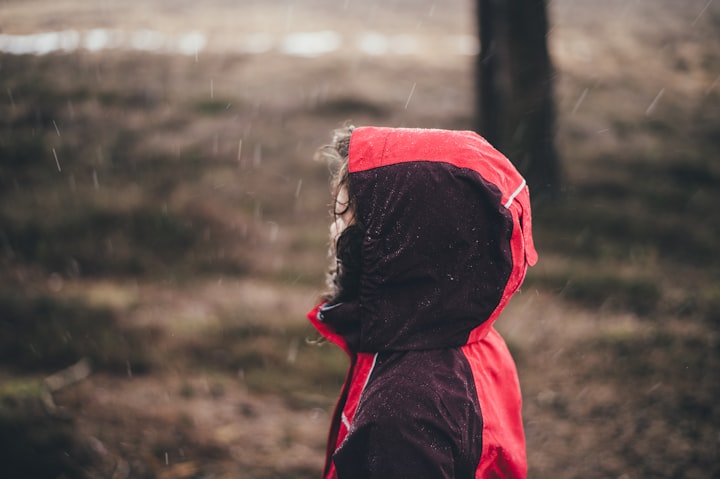

Boot prints were churned into the mud. My feet vanished into them as I hopped from one to the next as if they were stepping stones, my light-up trainers flashing red with every hop. It was drizzling and I was buried in the depths of a mackintosh. The hood kept falling forward over my eyes so I wasn't aware of my grandfather standing in the last set of boot prints until I collided with the back of his legs. My sleeves flapped as I teetered dangerously.

“Oops-a-daisy-dando!” A hand, tough as old rope, grabbed my collar and hauled me upright. “Watch yourself, lovely girl! If I bring you back all muddy, Gran will dunk you in the fishpond to clean you off.”

I squinted up at Grampa. Was he joking? I wouldn't have put it past Gran to dunk me in the fishpond. He flashed his wiry grin and I smiled, relieved.

He put his fingers to his mouth and whistled. All around us was an ocean of damp green mottled with heather and the gentle swell of the mountains rolling belly up towards the sky. His whistles had a way of taking off like a buzzard and soaring for miles. The sky was thick with blazing white clouds. I was snatching at bulrush reeds and stripping them down to the pale foam inside when Grampa pointed up the shoulder of the mountain. “Here he comes, babes,” he said. A sooty speck in the distance was flowing down the mountainside, proceeded by tumbling mass of white. The thud of hooves on soft turf made a rumbling like distant thunder.

“Slow and steady, Mister Splodge,” muttered Grampa. He turned to me and grinned. “Or they’ll be having baby sheeps everywhere!”

I shoved my hood back to watch the sheepdog herd the flock through the mountain gate and onto the farm road. My job was to run over to the gate and pull it closed behind them. After Grampa and Splodge had gone through, I followed and clanged it shut.

“All done. Let’s go have some tea,” Grampa said. Splodge came over and sat on my feet, panting up with his doggy smile. I patted his big domed head and ruffled his ears, not minding his stink or the wild damp that matted his fur. There was a thistle head caught in his ruff. It prickled the soft pads of my fingertips as I pulled it loose.

We walked, the three of us, down the long road towards the farmhouse. My grandfather’s boots clumped on the stone in rhythm with the tap of his walking stick. I tried to match my stride to his longer, loping one, thinking of the fire that would be crackling in the stove to melt the chill of early spring from my numbed hands and feet. I hurried along, and very nearly didn't see the lamb.

It was on an expanse of open ground to the side of the road, the no-mans-land where the tractors squatted in the rain and a few warped, prickly trees twisted up towards the sky, the ground between them littered with rusted machinery parts. A derelict caravan was half-buried in a nettle patch and beside it lay the barest, tiniest scrap of white. I pointed. “Look, Grampa. A lamb.”

He looked and a frown deepened the wrinkles on his brow. “Oh, aye. Must be dead,” he said and stepped off the road to go to it. I ran ahead, slowing as I drew close, afraid that he was right and it was dead. But it twitched. Then it wriggled. It murmured weakly and tried to lurch to its feet. The lamb fell back onto the grass, ribcage heaving with panic. I stooped beside it. Its head was swollen and its wool tightly-curled, bright and damp and brand-new. A slimy grey-pink placenta glistened in the grass beside it. I scooped the lamb out of the dew-soaked grass and wrapped it up in my arms. It weighed almost nothing. It was a bag of bones and feathers with blunt legs that dangled limply.

Grampa stood beside me, leaning on his walking stick with his heavy boots crossed over each other at the ankle. His bushy eyebrows knitted together as he looked down at me with the lamb in my arms. He was a short man and sinewy, but he towered over me, dark and tall against the blinding white sky. “Can you see it’s mother?” he asked.

His eyes were going bad. I gave the field a brief scan. There was grass, rocks, and that was all. I shook my head, wondering why it mattered. The lamb’s mother didn’t want him. I could feel him breathing as I held him gently against my chest. He’d gone still and his eyes were half-closed. I wondered if he had known warmth at all, before I had come along and picked him up. We would take him back to the cottage and give him warm milk out of a baby's bottle, like we’d done for the lost lambs last year. Gran had kept three of them in a cardboard box by the fire like bleating white puppies.

Splodge came over and sniffed at the lamb with interest. I held it higher. Splodge was a good dog, but he ate the sheep if they died. Splodge sat down on my feet, thumped his tail and smiled at me. Grampa pulled down the peak of his cap. He sucked his teeth, considering, then beckoned at me and headed back towards the lane. "Come on, then. We'll put him with the others."

The words stopped me short. “Aren’t we going to take him back with us?”

Grampa didn’t look back as he strode on. “We’ll come out later and if he’s not found his mother, we’ll take him to the house.”

“But his mother doesn’t want him or she wouldn’t have left him! She won’t take him back! We have to look after him or he’ll die!”

Grampa ignored my protests and continued up the road to where the huge flock of sheep were idly munching grass. A few lambs were already gambolling amongst them, strong and sure-footed. My lamb’s head was resting listlessly on my arm and his eyes were drooping closed.

I marched off towards the house, but my grandfather’s shout made me stop. “Emma Jane!”

There was warning in his voice – a sharp note, an unspoken or else that froze me in place. “That’s enough, Emma Jane. Give him here.”

“No, we have to take him with us.”

“Now.” An outstretched hand loomed, big and creased and rough. My own hands, small and soft and pale, clutched the lamb closer to me. My fingers curled into his wool. I hovered between defiance and obedience while that hand loomed, insistent.

"Do as you're told, lovely girl.”

That was always what I did. What I was told. Even when I hated it. Even when it felt wrong.

I gave the lamb up. Grampa took it and straightened up. He carried the lamb back to the flock and set it down. It took the lamb a moment to find its legs and then it wobbled off, bleating desperately. We made our way back to the house, the lamb's cries fading behind us. Each one caught and stung like the barbs of a thistle in tender skin.

I thought of nothing else all day. Every time I asked my grandfather if it was time to go back to the lambing fields, he answered: “After dinner.” The meal came and went. I barely touched what was on my plate. Grampa had seconds, then thirds. By the time the last of the roast chicken had been sucked from the bones heaped on my grandfather's plate, I was already up and putting my coat on.

"Where are you off to?" Gran asked, her eyes narrowing behind her wire-rimmed glasses.

"To look for the lamb." I was halfway into my wellies.

"You're not," she said, and the edge in her voice sliced neatly through my sails, letting all the wind out. I gaped at her and pointed at Grampa.

"But he said after dinner, we'd go!"

"I don't care what he said. You're having a bath."

"But..." I looked to Grampa, who was now starting on a slice of fruitcake. "I never have a bath!"

"You're stinking dirty. You've been playing with those bloody dogs again! You're having a bath."

"That's not fair! I have to look for the lamb!"

"Grampa will go. Kate can go with him."

I looked at my sister who was sitting meekly at the table. She looked back at me; eyes wide. "Kate doesn't even want to go! Do you, Kate?"

Kate looked terrified. "I don't mind," she said.

"Kate can go, you're having a bath and that's the end of it."

In the bath, I cried and screamed. Gran ignored me as she scrubbed shampoo into my hair, occasionally clipping me across the head for whining. When I emerged from the bathroom, sullenly quiet and smelling faintly of lavender, Kate and Grampa were gone. It was pitch-black outside the living room window when the porch door scraped open and they came in from the cold. They were empty handed. After stamping the mud and cold from their feet and shedding their overcoats, Kate hurried over to me and said "We couldn't find him. We looked everywhere." Grampa put a heavy torch on the table with a thud.

"You couldn't have looked everywhere or you would have found him," I snapped. She crumpled.

All night, a cruel wind hummed against the windows. I lay awake for most of it, pinned under a pile of thick blankets with Kate asleep beside me in the spare room. Cobwebs hung from the beams on the ceiling, waving gently in the draught. When I did sleep, I dreamed of the lamb, lying dead in the corner of a field like a broken ragdoll, bone-white in the dark.

Grampa came in from his rounds the next morning and sat at the table to eat breakfast. Kate had gone out with him. She had told me that they had found the lamb dead in the corner of a field. She apologised as if that might make it better. By breakfast, I was done crying and had resumed my silence. Grampa buttered his toast and poured a cup of tea from the pot. Eventually, between slurps of tea, he looked at me from under his eyebrows. They were knitted in a frown. “Are you still sulking about that lamb, Emma Jane?”

My resolution to never speak again crumbled. Anger licked at the back of my throat and I pushed words out, though they trembled, and I wanted to shout them - so loud that they would shatter the windows and the wind would blow the fire out, so he'd know how it felt to be stuck in the cold. “The lamb would be alive if you’d listened to me,” I said.

He bristled. There was a long, heavy silence. Then he said, “Don’t talk to me like that, lovely girl."

I ate the rest of my toast in silence. He drained off his tea, set the empty cup on the saucer and stood up. He tugged on his cap. “Time to feed the dogs,” he told me.

He waited for the moment I would leap up, scramble into my coat and wellies to follow him. It didn’t come. He tied his scarf and went through the door. His walking stick tapped and his boots shed mud onto the garden path. Splodge heaved himself up and followed at his heels.

I watched them go.

About the Creator

EJ Ferguson

EJ Ferguson is a UK-based writer and occasional poet. She holds a BA in Creative Writing from University of South Wales, and is perpetually working on a debut novel. She is often found buried beneath soft blankets and two enormous cats.

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insights

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

Compelling and original writing

Creative use of language & vocab

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.