Ironing, Piano, Nuns, a Psychic, and Coming of Age

A Father's Nightmare and a Young Boy's Dream

I’ve had lots of turning points, but the one that marked my coming of age, I’d place that one when I was 18 and in my last year of high school. We moved a lot when I was a kid. My father was an engineer. He designed cranes, conveyors, and overhead highway says, mostly for small to medium sized companies all over southern Ontario. I usually felt like an outsider, but I don’t blame that on moving, more on being a misfit, and not trying hard enough to make friends.

First some background. When I was 15, my dad took a new job in London, Ontario, a good job, good challenges and good pay, so we pulled up stakes from our home in the up-tempo city of Burlington and moved to very conservative London. I liked it in Burlington. I excelled in math, and those teachers let me forge ahead, take the next grade, learn about computers. Of course you would laugh if you saw the huge size and tiny computing power of those dinosaurs, but I loved it. The English teacher gave me a key to the book room, so that I could read all I wanted (and I did). I was an outsider, but I was thriving.

I left that good stuff and my two best friends behind when we moved to London. Still, I was adaptable. And there was a bonus: my favourite aunt lived there, and four great cousins.

I had studied the piano long enough and seriously enough that finding a good teacher in London was an important part of the move. My Burlington teacher referred me to the convent school where almost all the serious young piano students went to study with the sisters. I was looking forward to that.

But matters took a different turn. My father had gone ahead to work in London, leaving me and my mother behind to sell the house and pack up. One of my cousins was playing the bassoon in her high school musical and my father attended the performance. He thought the boy playing the piano did quite well, and at the end he asked him who his teacher was.

She was and is amazing, a prof at the university, a recitalist, and, I later learned, a world-class pedagogue.

She couldn’t fit me into her schedule, so I studied with one of her senior university students, and that suited me. He was just six or seven years older than me, very bright, a fine pianist, and I looked up to him. I tripled my practice time.

And no special math, and no key to the book room, just a well-meaning, slow-moving math teacher who wanted me to draw diagrams with a ruler. And English was pretty lame. But music. Ah! That was great! And I played in the band and sang in the choir. And we had a dog, an eccentric German Shepherd, an overzealous guard whom I walked three times a day, a watch dog who had to be watched. He was very clever. He learned the routine of the house in one day, and was waiting for every event on the second day. Of particular interest to him was the mail slot in the door. As the envelopes came through the slot he grabbed them with his teeth. And some of those bills came on old punch cards! He would not be talked out of that, however hard we tried… smart and stubborn!

Ontario high school went to grade 13 then. I had done grade 9 and part of grade ten (the math and English) in Burlington, so I was partly in grade 10 and partly in 11, and I finished high school in London in 3 years.

Flash forward to grade 13, lots of us planning on post-secondary studies. Most decided to live at home and attend the local university. Does it sound like the movie American Graffiti? Well it was like that, a fair bit. But, after talking with my piano teacher, I decided I would spend the next year studying the piano in Europe. After all I had done the five years of high school in four. Now it’s really sounding like American Graffiti isn’t it?

There were wrinkles. After all, we learn through wrinkles. Wrinkles in time, wrinkles in plans. I wanted to go to Europe, and told everyone that was what I would do. I don’t think I said it in a very humble way at school or at home. At 18 humility was not my strong suit (it still isn’t—no one is perfect). Complicating the question, the local university decided to offer $1500. scholarships to the students with the best grades.

I was not a mark grubber. I spent my time practising the piano while other students went over their neat notes. On the other hand I didn’t need that study time to get high marks on exams. Maybe I would lose a few marks for diagrams not drawn with a ruler on the exam, but still I could do well with a bit of effort.

My father was opposed to my plan in two ways. First of all music was uncertain as a profession. He was right to think that. It was and is. Secondly, going to Europe? Why go to Europe with a good university just around the corner? It was and is a good university, so he had a point.

We argued. 18-year-old boys argue with their fathers anyway, and we went at it verbally, hammer and tong. At Thanksgiving my uncle said to us both, “Would you two please bury the hatchet for the day?”

And my aunt was an important part of the context. She was a wonderful, impressive lady. She had been the first in the family to go to university, and she taught Latin and French in high school. She believed in education, and in the arts. She taught me about bridge and Boccaccio. She was diagnosed with breast cancer, and it was very important for her and my mother to have the time together, while my aunt fought the good fight, radiation and chemo, which were even harder on people in 1977 than they are today. I adored my aunt, and spent lots of time with her and my cousins.

One night I had a vivid dream that I would study in Europe. I saw a garden, a villa, and music students. So my hopes were validated, and I didn’t shut up about it. I also did not make much of an effort in the pursuit of the large scholarship, because I knew that if I won that, there was no way my parents would countenance my studying in Europe. I suppose some psychologists would call that self sabotage, but to me it was just common sense—don’t wreck the dream!

I had a lesson with my piano teacher’s teacher as I prepared the pieces I would record in a studio and send to Europe as my audition. She was, among other things, a master of gesture, more than any teacher I have ever known. She didn’t want to change much (sensitive teachers don’t change much when a student is about to perform), but there were two measures of my Haydn piece that she offered a gesture for. She said to play them with the same weight as if I was ironing clothes, and she worked with me until I got the gesture right. I was to practise it that way, and play the short passage just like that. I worked at it.

I made the recording and sent it off to Switzerland, Austria, Germany, and to a school in Florence that was an extension of a midwestern U.S. Catholic university. Over the summer my classmates got those large scholarships. I did not. One of them said to me pointedly, “You could have had this scholarship if you had tried.” It was the truth, and it hurt a bit, especially since I got turned down by another European school every couple of weeks. Still I kept up my line, to my friends, and especially to my cousins. I think my aunt told them not to trash my dreams. My father continued his objections to my plans, but started to relax because he thought they would not come to fruition.

My father was a devout Christian, but, or and, one of his hobbies was, how to put it? Psychic phenomena? Mediums? He explored this in every conceivable way and was frustrated that I showed no interest. He read that boys could see prophetic images in a glass of water and made me stare at one for several minutes while I told him I just saw water. Late that summer he persuaded me to go with him to the local Spiritualist Church (which was not our denomination). After the hymns, they featured a guest medium. My father could hardly wait for the medium. I wondered how I’d been talked into going, but it was better than having yet another argument with the father I loved and quarreled with.

My mother wanted nothing to do with Spiritualism or psychic things, but the sight of her husband and son going off together peaceably gave her quite a bit of comfort. The hymns were unusual. I concentrated on them. My father waited impatiently for the feature. Finally the guest medium was introduced. He wasted little time: “The spirits have an urgent message for someone here.” That got the congregation stirred up. “It’s very important, and it’s so very clear.” He surveyed the gathering, most of the people on the edge of their seats.

Horror of horrors he fixed on me—“The message is for you, young man, and it’s so clear. They’re all saying it.”

Rats! It was too late to make a run for the exit. No trap door either. Best, I thought, just to take the humiliation on the chin, wear it for a while, and let it fade away. “The spirits are all saying, they are insistent, they want you to know that—” Could this guy drag it out any more and make it worse, I wondered, please just deliver the line and leave me alone. Meanwhile others were no doubt thinking they had come for a message from the other side and why should a newbie like me have all the luck?

“The spirits say you must listen to your father!”

That’s it? I thought. Really? And I’m going to believe that? Had Dad slipped him a twenty? Apparently not. Dad beamed and put his hand on my shoulder. And that was that. No spirit messages for anyone else, only lucky me. And such a welcome message! I thought he had better keep his day job. All the way home my father repeated, “It is so fortunate that we came tonight, don’t you think? A message for you! An urgent message.”

I didn’t think it was fortunate at all. I only marvelled at my father’s restraint. He didn’t say, go to the local university. I supposed he would wait a day or two for the medium’s words to sink in before he drove that home.

That was the last week of August. In Canada university begins just after Labor Day. The next day, my older male cousin sat me down to talk seriously. He said university was about to start. I’d won a smaller scholarship and I should be preparing for classes. He pointed out that I’d been rejected by all European schools except one, and at this late date, it was not going to happen. He said I had tired everyone out repeating the impractical idea I was hanging on to. He said it was time to give it up. Then he left.

Even for a cockeyed, optimistic 18-year-old boy who’d dreamt about his dream, the impending reality was enough to tip the scales. I was raised in a Christian group that favoured discussion and Bible reading over revelation. I had read the Bible, and I had listened to discussions. Overall I was not experienced in prayer other than formulaic ones. That night I decided to try. I don’t know if I thought I was talking to God or Spirit, but I softly spoke an apology. I said I was sorry for my arrogance, for the idea that this university was not good enough for me. I apologized for being a repetitious, vain pain to my cousins and classmates, and especially to my parents, most especially to my father. I gave thanks for the opportunity to study at a university and I resolved to try not to be so pretentious in the future. I gave up on my dream, and apologized for holding on to it when it had obviously upset people who only wanted the best for me. The giving up part cost me a tear or two, but I soon fell asleep, the German Shepherd on one side of the bed, and the canary on the other.

I didn’t wake up until I heard the dog dash to the mail slot in time to intercept the envelopes. I followed him out to the front door, and watched him chomp down on the day’s post, then took it from his mouth. There were bills, but there was an envelope addressed to me with Italian stamps.

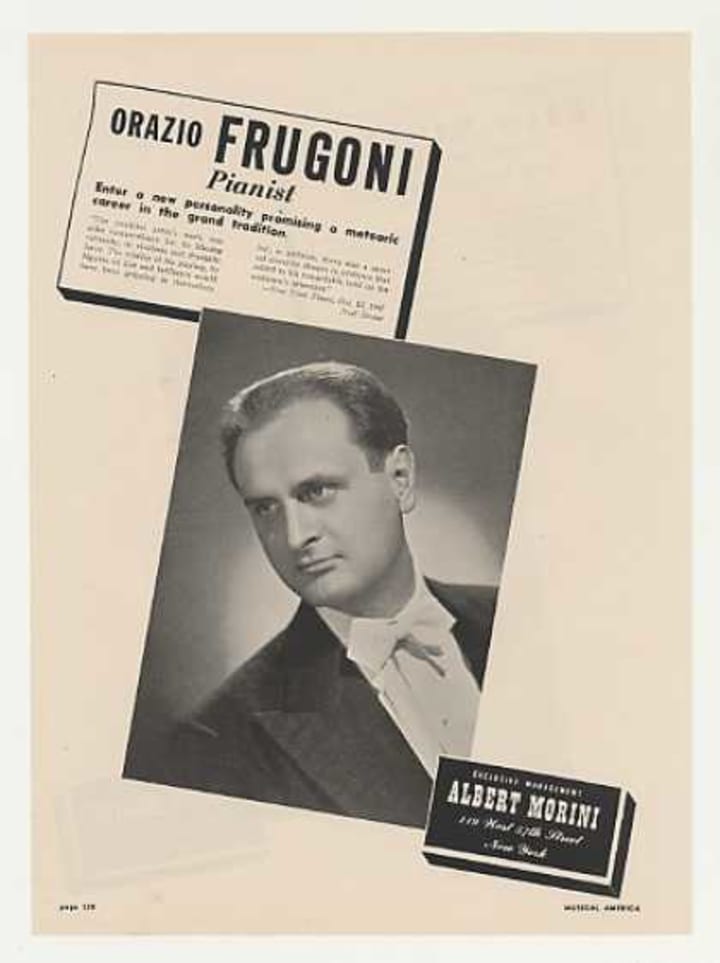

“Dear Mr. Merkley, Thank you for your tape. I would be pleased to teach you in Florence. Please come right away. Orazio Frugoni.

Wow! But what would my mother and father say? I showed the letter to her right away. She was pleased I had been accepted and she told me to walk the dog. I can imagine there was a phone call to my aunt while I did that, then another to my father. When I got back she said we would speak when my father came home.

My aunt and uncle came to supper that night too. And my father was reconciled to the idea. They had looked up my future teacher and learned that he had cut fifty recordings. Also the lira (pre-Euro days) was very low, and it seemed clear that it would be cheaper for me to travel to Italy and spend eight months there than to live at home and eat groceries. Really, it was.

The next morning I ran to school to find my French teacher. I asked him how I could learn Italian quickly. He said to get Teach Yourself Italian and learn the verbs. I bought the book and started on it right away. My piano teacher was thrilled. I was thrilled. I got a plane ticket and a hotel reservation for the first night.

I mailed most of my piano scores by Thomas Cook, packed a bag with six or seven of the most important ones, and said goodbye to family. My aunt gave me a yellow flower as a boutonniere. She was almost as excited as I was.

I couldn’t sleep on the plane so I studied my Italian book. I booked a room with kitchen privileges at the hostel down the street from my new school, actually a monastery.

I was asked to write a music theory test right away, to see what theory I would need. I protested that I couldn’t afford another course, but I was told that Maestro insisted, so I wrote the test, groggily, and then feeling sick. There was a dictation exercise. The examiner played the tortuous “Tristan Prelude” for us to write out. Most groaned at that, but I wrote it down. All of the others were graduate students. I was enrolled in a “performance certificate,” just piano lessons.

The school was administered by sisters of the Dominican order, so I got my experience with nuns after all. I made the mistake of wearing shorts one day, and was sent home to change!

That afternoon all the students met in the room with our mailboxes. There was an awkward silence. I broke it by saying something about Star Trek. Instantly we all began talking with each other.

Two days later I had my first piano lesson. I spoke in the best Italian I could muster. Maestro’s eyes opened a little bit wider. I said I did badly on the theory test because I was feeling unwell. He remarked, in English, that I was already speaking Italian passably and asked if I was feeling better. He recommended something at the pharmacy. Then he said, “As for the theory, you did better than all the graduate students.”

Then, without skipping a beat, he turned his attention to a tape recorder. He said "I want to show you why you are here. This passage is very good." He turned it on, and I heard the two bars of Haydn that I had “ironed.”

“This is very good,” he said. “We can work on the rest.” And so we did. And I matured from an anxious teen into a young adult musician. I learned Italian well, took advantage of all of the arts and culture of Florence, and later came back to Italy to do my own research. I returned to Canada just in time to meet my future wife in first year university. Coming of age.

About the Creator

Paul Merkley

Co-Founder of Seniors Junction, a social enterprise working to prevent seniors isolation. Emeritus professor, U. of Ottawa. Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. Founder of Tower of Sound Waves. Author of Fiction.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.