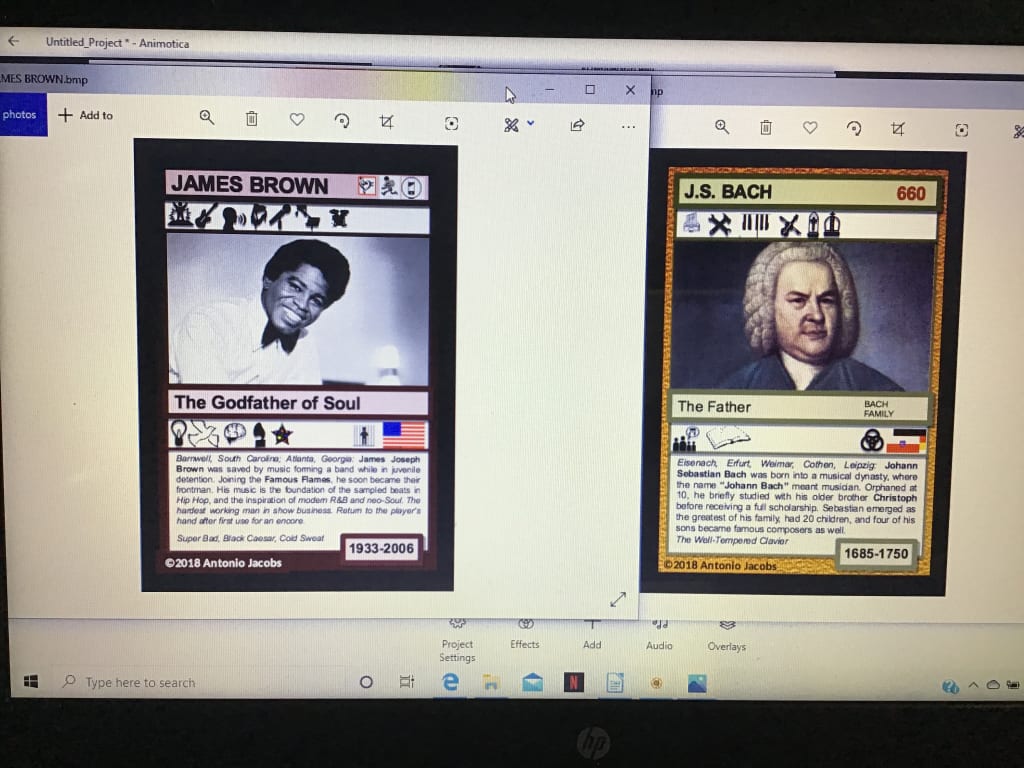

James Brown: Bach of the 20th century

Similarities between The Godfather of Soul and the Father of the Baroque Age

What happens when a musical genius is not nurtured, neglected a classical education, raised in abject poverty by someone other than his biological parents, criminally inclined, chemically altered, and battered by tragic circumstance? You get a man whose music was able to nurture not one genre but four, feed the creativity of four generations of musicians, provide a comfortable life for himself and his family, politically charge a nation, and rise out of bleak obscurity to become known as The Godfather of Soul. James Brown lived a full and tumultuous life, one that mirrors his era, and reflects the struggle of the African-American male in the twentieth century. Brown’s songs examine the pain and realism found in living as a black man in the United States during a time when the status quo of segregation was being challenged. His songs “It’s A Man’s World”, “Say It Loud”, and “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” became the anthems of the poor man, the black man, the lover and the fighter.

James Brown as a musical force is dripping with similarities to another great man of music, the incomparable Johann Sebastian Bach. Both are products of their environment; though 240 years apart, they share a spiritual connection. Musically, they attained a level of genius not fully comprehended. Bach invented so many tools and theoretical concepts that his Sunday alone provides the foundation of any fledging musician’s practice regimen. In contrast, Brown ignored the rules and concentrated on what sounded and what felt good. These two maestros are prime examples of the possibilities of mankind. They demonstrate passion, nationalism, pride, ego and a prolificacy unmatched by most.

Although they are at first glance quite different, the similarities between them are staggering. They wear similar hairstyles; they were of similar temperament; they lived a lot, they loved a lot and they poured their souls into their music. Most importantly, their music becomes the foundation of their respective genres, thus ensuring that their music survived, while also infusing life into the genres that follow. Both were cursed with a period of stagnation – Bach after his death, and Brown during his life – followed by a resurgence rivaling the popularity of any musician past and present.

Both Bach and Brown lost their parents at an early age: Bach’s parents died when he was nine; Brown’s parents separated when he was four and left him in the care of his aunt. Both received musical training in their childhood, although Bach, being from a family of musicians, probably had an earlier and more comprehensive start. Brown seemed to learn to sing and dance through trial and error, making a modest living on the streets. Both were well versed in church music: a musician in Bach’s day would have to work in the church or as a court musician, or perhaps as a "beer fiddler." Brown hooked up with the gospel circuit in Georgia after a stay in prison for armed robbery at the age of fifteen. Both Bach and Brown grew up poor. Bach was sent to Latin school and paid his tuition through service in the Boy’s choir. Brown grew up in a brothel, shined shoes and felt inclined to participate in petty theft occasionally to eat. Musicians of any era rarely make a good living.

In Lüneburg, Bach had access to an extensive musical library, sang and played well enough to get paid and left a virtuoso. Brown learned organ and drums while playing gospel music under Bill Johnson and Bobby Byrd. Virtuosity is measured by a musician’s mastery of their instruments. Bach and Brown had ample opportunities to practice multiple instruments, and in time both developed mastery in several. Oddly enough, this simple characteristic of both musicians is often overlooked by the layman; Bach is primarily known today as an organist and a composer. Brown, as parodied by Eddie Murphy, is reduced to a minimalist singer and accomplished dancer, and yet nearly all of his songs are his by design - from concept to recording to stage, not to mention his skills as a keyboardist, bassist and drummer.

Both Bach and Brown loved the women. It is said that Bach was attracted to both music and the opposite sex, traveling on foot far distances for both. While in Arnstadt, a rather small town, Bach was paid well for his services as a church musician, though he was evidenced to have had a dalliance with a “stranger maid.” This dalliance was said to have occurred in the wine cellar of the church. Bach was married twice in his lifetime, and sought to be as prolific in his family life as he was as a composer. Had he lived in a time where health care was more sophisticated, Bach may have had 20 heirs to his legacy. As it was, four of his sons – two from his first marriage and two from his second – were at various points in their careers as famous or even more famous than their father. Wilhelm Friedemann inherited his father’s talents for improvisation but died poorly in 1784, while Carl Philipp Emanuel appeared to have inherited Johann Sebastian’s penchant for immortality. Johann Christoph Friedrich was successful during his time, and Bach’s youngest son, Johann Christian (aka Giovanni) had direct influence on another of history’s great masters, one Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Brown was said to have had affairs with his background singers as a matter of convenience, perhaps, or maybe because music was as important to him as sex. Brown was married four times, and reports vary as to the number of his children, although the most likely number is twelve, including his late son, Teddy, who died in a car crash in 1973. Like Bach, one of his marriages ended with the death of his wife Adrienne Lois Rodriguez, who died in 1996. Brown's last marriage also parallels Bach’s second marriage, in that there may have been dissention between the children of Bach's first wife and Bach's second wife. In Bach’s case, his second wife died in poverty, as Sebastian’s grown sons from his first marriage did not provide for her after his death in 1750. Bach did not leave a will, which understandably left all sorts of legal problems. Brown’s saga is in process at the time of this writing: his current and fourth wife, Tomi Rae Hynie, was barred form Brown’s home after his death under spurious circumstances regarding the legitimate nature of their union. There is a possibility that Ms. Hynie may share a similar fate to that of Anna Magdalena, Bach’s second wife, who, like Ms. Hynie, had no adult children to support her.

The composers differed in the early part of their careers. While Brown struggled on the gospel circuit during his 20’s, Bach was enjoying modest success as an organist and composer by age 22. His growing ambitions led him to Weimar, a larger town with a position that doubled his money – an important detail since he was now a married man with children. In contrast, Brown was 33 before attaining relative acclaim with his first hit “Please, Please, Please” in 1956.

In Weimar, Bach was prolific, required to write one cantata a week, literally inventing repertoire that is still used today. The political climate in Weimar was fragile, and Bach’s position as church musician was precariously balanced on the whims of the local aristocracy. Destined to be greater, Bach soon outgrew his position at Weimar, which had become unsuitable after a fire consumed a large portion of the town, and Bach duties subtly changed from composer to architect. Like the godfather of Soul, the father of the Baroque spent some time in prison – as a result of applying and accepting a position as Court composer at Köthen, for Leopold von Anhalt Köthen, without the express permission of the Duke of Saxony, Wilhelm Ernst .

The 1960s were a very prolific and profitable time for Brown. He enjoyed commercial success, earning 7 songs on the Billboard Top ten, played throughout the world with his band of highly trained and well rehearsed musicians, and become known as the “hardest working man in showbiz.” Brown was also enlightened about the music business, securing his own publishing, controlling his royalty stream through the acquisition of radio stations and disc jockeys, and constantly performing. Unlike Bach, whose influence extended initially only through his family members and students, Brown lived in an era where his music could reach millions, and he became popular in the United States and overseas.

Unfortunately, this success would not last for James Brown in his forties, as he watched his career, his personal life and his finances wane. As Disco, with its technical sound increased in popularity, the opportunities for live music performance started to decline, and the DJ emerged as the driving force in music. Brown was not able to adapt after the personal battle he was facing. The death of his son Teddy in a car accident was a tremendous blow, while his second marriage to “Deedee" Jenkins ended in divorce. The government seized much of his possessions, including his radio stations after allegation of payola. This triumvirate of misfortune took its toll on Brown, culminating with his arrest, conviction and imprisonment at 54. After years of turmoil, tragedy and disappointment, Brown was reaching the end of his Job-like story.

Meanwhile, in the eighteenth century, after his nine years at Weimar, Bach lived comfortably and at the pleasure of Prince Leopold in Köthen for another six. Like Brown, Bach suffered close tragedy; by this point three of his children had already died in childhood (although four had survived), and his first wife, Maria Barbara, had succumbed to illness and was buried while Bach was away from home in 1720. Also like Brown, his musical success was not to last, as interests in Köthen were declining (probably due to a lot of factors – Köthen was the equivalent of Nutley, New Jersey compared to, say, Philadelphia or even New York City), and Bach and his increasing clan sought more lucrative employment elsewhere. Besides, his benefactor, Leopold, lived to the ripe old age of 33, living a mere three years after Bach’s departure for Leipzig.

Both Bach and Brown struggled financially. In Bach’s case, his primary income came from church music, which in various locations, became less and less lucrative. Considering the size of Bach’s family (he and his second wife produced twelve children, of which eight survived to adulthood), Bach’s bills must have been considerable. Like any musician, he sought to acquire alternative streams of income: playing funerals, honorary titles and teaching among them. Brown’s financial troubles were connected to income tax; the government took many of Brown’s assets and properties during the 70s, and his stay in prison in the late 80s certainly did not put food on his family’s table. The amount that James Brown lost on royalties alone during his incarceration is nearly incalculable. It took a return to the road for Brown to achieve solvency again – a condition many musicians intimately know.

Up to his death at 75, James Brown kept working. He was scheduled to play B.B. King’s Blues club on New Year’s Eve of 2006. His death from heart failure brought about by complications from pneumonia was unexpected. At the initial time of this writing, James Brown’s body, which was being kept in a climate-controlled room in his Columbia, South Carolina home, moved to an undisclosed location while the surviving members of his family discussed the distribution of his estate, before finally placed in a crypt on his daughter’s property, Deana Brown Thomas.

Bach’s final years were plagued with blindness caused by cataracts, probably brought on by diabetes. In early 1750, an unsuccessful surgery is performed on Bach’s eyes by an oculist named Taylor, who is fated to perform the same procedure unsuccessfully nine years later on another Baroque legend, George Frederic Handel. By this time, however, Bach has managed to secure himself as a renowned and respected composer. He also has enough talented children to enable his music to be published and preserved for future generations to come. Two things are certain: Bach’s voluminous output increased his chances of maintaining immortality; and his children, who were trained in music and who lived in the center of musical importance during the eighteenth century, enabling a wunderkind named Mozart access to genius.

Working as a musician in the eighteenth century was not unlike working as a recording artist in the 1960s – both were under stifling contracts; both were underpaid and overworked; both were limited in their options for alternatives. Despite these pressures, our two subjects were able to produce the most profound and memorable classics recognizable by most ears at a moment’s hearing. They were able to invent new forms of music that later musicians would barely be able to emulate. They were both so prolific, that even the most arduous of fans will probably only hear a fraction of their music during a lifetime. Over 1100 works are attributed to Johann Sebastian Bach; his official catalogue is no doubt incomplete. James Brown released over 100 albums, and once said,” I've outdone anyone you can name -- Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, Strauss. Irving Berlin, he wrote 1,001 tunes. I wrote 5,500.”

About the Creator

Antonio Jacobs

A lifelong New Yorker, Antonio writes fiction and non-fiction and is a musicologist who believes that The Wizard of Oz is the template for all films ever made.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.