Content warning

This story may contain sensitive material or discuss topics that some readers may find distressing. Reader discretion is advised. The views and opinions expressed in this story are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Vocal.

(Finding the Wings): Painted from Life

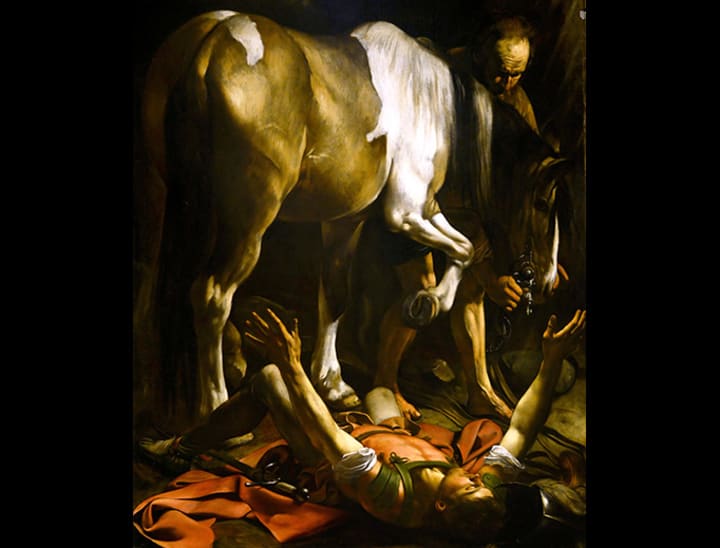

Amor Vincit Omnia, 1601-1602, by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

DISCLAIMER: Contains violence, minors in compromising situations, some strong language. I have used experiences from my own boyhood to lend realism to the persona of the young hero, Cecco, but most events are drawn from historical fact.

FIXED FOR FLIGHT

Indeed you could imagine them, and then from these imaginings paint them: these famous wings. Yet to really paint them, as if from Life, in the wings of a bird, in the wings of a seraph, and in those feathers of the most formidable Archer and little god of Love, a truly great prop was needed. The maestro was obsessively insistent about these Real Wings from a real eagle, to make his picture a masterpiece; he sulked for nearly a week, not being able to obtain them. Otherwise, he had everything else he needed to begin: first and foremost, he had Cecco.

It was from among the treasures hidden in the ramshackle studio of his fellow artist Orazio Gentileschi that he at last received the coveted prop: brown eagle wings, spread like in flight by their setting in a frame of wicker, attachable with imperceptible ties at the shoulder. The urgency of the repeated letters sent daily requesting the wings astonished Orazio, and he let him into his atelier one balmy summer evening displaying a certain degree of irritation while dismounting the wings from a wall.

"Off with you then Michelangelo, dog of Caravaggio--I have no idea what degeneracy you're planning with these, but I leave you to it. Now, I have some work to do myself, so," with a gesture of his hand, "if you please--" and he led signor Caravaggio to the door with his wings. "And give my regards to your little Cecco. They say you intend to make him into a painter."

Who was now denuded IN MID-POISE:

his name is Francesco Buoneri,

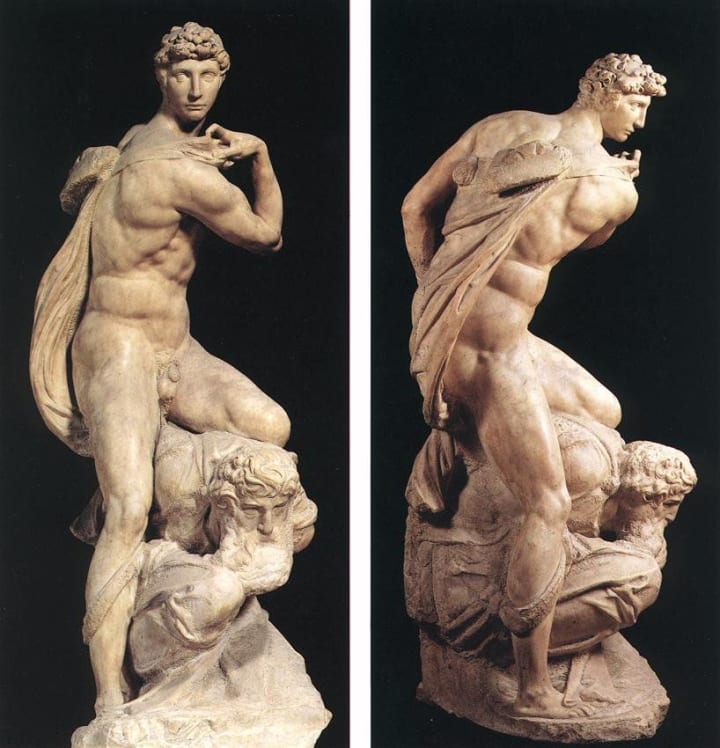

Holding it. This is the Studio, this is now home for him. A chance at an [almost] honest life for him. We come upon the boy mid-pose, as starkly naked from toe to crown as he can be, while he grins a cheeky grin that overdimples his face. His dark mop of tasseled and berumpled hair makes him look as if he's just gotten out of bed, or is just getting into bed. He holds a half-twisted and self-hoisting posture derived in part from a marble sculpture chiseled a hundred years before by Michelangelo Buonarotti: an Allegory of Victory. The maestro had made sketches from life of this sculpture, and had shown Cecco the form of the pose he wanted to modify. Now holding it, relatively still.

This is now home for him, this is the studio and workshop.

"Oh maestro, why why why must I stand for so long like this?" holding the grin effortlessly.

"Stay still Cecco. I'd have thought you'd be used to it by now. This is your job you know, until you become a painter. One day you will do this too, even if it's only in form of a flower. So don't move too much, per favore."

The form of the pose retained, the boy rests himself on what could be either a bed or a table, draped with white linen, surmounting a jumble that staged a Still-Life, mostly discarded to the floor. Allegorically, the force of Amore was greatest of all forces, armed yet naked: he terrorized the hearts of men and women, perpetually victorious over their fates. However, here he carries no bow, but only the two arrows, crossed against one another. Musical instruments strewn, a viol and a lute, and folded pages of musical notation; trampled armor on the floor with the instruments of war scattered; a compass and a sculptor's chisel nearby; on the table [or bed] a prop crown and a prop scepter. Meanwhile, in the distorted right triangle formed within the boy's legs, there are both a fading laurel wreath, and a book of poetry, open. Piled like junk, were the very diadems of kings and queens Love was said to trample beneath his feet: Love conquers all better than death conquers each. A globe mapping the constellations and other celestial figures lies behind the lad's right thigh, a crescent sliver of it is visible. The two arrows, dreadful darts, are clasped loosely in his dirty right hand. Threatening with them? Offering them?

CUPID COMPOUNDED/In a Game of Shadows and Light

drawn from many sources

with all the streetwise and self-confident smirk of Cecco, but embodying the arcane of winged Cupid

with his rumpled hair and grimy hands

It was a very lived-in place, a very worked-in place; he had already been the maestro's apprentice and model for two years now. It had its ups and downs, but the Bed was safer than the Street, by far! Bed and table, room and board, were identical to work and to studio. This was ample space for the workshop wonders, Masterpiece after Masterpiece, by the most famous artist in Rome now. And that Cecco could be a part of it! which came at cost, though.

What seems to be a table, like for a still-life, inserted into a portrait and a history painting at Once: the Myth of Cupid.

Crumpled white cloth suggests a table? or a bed?

Presently, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was working in pure blacks and browns: the tableau was bathed in oily jet except for the space set out in darkish greys for the figure of the boy. He could now work on preliminary swaths of the outline and tints for the human figure, even before the background dried. He liked to work fast and feverishly. Nevertheless, it took time and many standing sessions to bring it all together, this gradual build-up of liquid layering, but rapid.

Francesco retained his signature smirk, grinning thinking to himself how funny it was that he had been grinning for so long.

In mid-pose, a

DIALOGUE [begins]:

"Cecco,"

"Yes maestro?"

"You remember what happened to Apollo, when he teased his fratello Cupido, mocked his bowmanship, told him he was too small to use a man's weapon or to be an archer? You remember, no?"

"He--" as naked Cupid almost lost his balance, attempting to threaten with his arrows, "STRUCK him with an arrow of Love!" Cecco chuckles, rights himself. "Dardo d'amore!"

"An arrow of gold, dardo d'oro--making--"

"Him fall in Love with Daphne, a beautiful wood-nymph, maestro--"

"No, a beautiful nymph of rivers and springs; ma, molto bene. Apollo in turn struck Daphne with an arrow of lead, having the opposite effect--"

"Dardo di piombo, making her hate him and want to run from him. So, maestro, just like you were reading to me, he kept chasing her and when she came to the banks of a river, she prayed to the saints and Holy Madonna--"

"She prayed to the god of the river."

"Si, she asked the river-god to rescue her. And he did. She was metamorphormed right then and there into a Tree."

"A laurel tree: her toes changed into twisting roots, digging deep into the soil; her fingers transformed into entwining branches. Apollo wept... and so Cupido gloated over his Victory against his brother, knowing that this heartbreak would serve as a lesson to future generations never to deny the numinous might of the little God of Love, most fearsome Archer, although tender. And now, do you know what the laurel or bay tree is for?"

"Yes-yes! for seasoning a ragù! no, just a joke, solo una battuta maestro. The Laurel Crown is for rhyming men who make the best verses to be crownd in the Contests. Apollo is the god of poems. The Laurel is a leaf of Victory!"

THE WINGSPAN OF THE BRUSH

Although, pondered the artist to himself, there will be no winning of contests with this kind of work. Not that obtaining major commissions was a problem; however, the churches usually rejected his work as too vulgar and disturbingly stark for worship, and he would have to bastardize them to gain acceptance. Nevertheless his bold technique was widely revered by connoisseurs.

"Of course Cecco, it is also for seasoning a ragù."

Michelangelo Merisi always did it this way, painting directly onto canvass from live models, without the use of preliminary drawings. To bring reality from nature and layer its heated impressions onto the canvass successively, until dried and fixed, they take the light just right.

He was leader of the School of Shadowists (i tenebrosi), who reveled in a thick and unctuous obscurity illuminated by a violent shaft of light, cast upon subjects shown purposefully in all their natural flaws and defects. That light, that darkness, and the cast of each natural asperity, he believed, could engage all of the inner harmonies and conflicts of both Subject and Painting as a totality: in the right light.

Chiaroscura was the keystone of his painterly doctrine.

Then there was Cecco. Those who would claim that Cecco was the Object of his painting would be mistaken: he is the Subject of the painting. Simultaneously Cupid and Cecco at once, he could say it a thousand times a day, and never tire of the sound of his name, his voice, nor the look of his face. At first a perfect model for angels in general, he could do a young John the Baptist in hide with a scroll, maybe when he was a bit older as a David with the head of Goliath: always finding the right props. Yet what he most wanted was something more pagan--to execute a truly Roman Cupid, life-sized, frontally painted from reality in his full nudity, with all the grunge of the Roman street and of the art workshop--just as he knew him even awakening from the slumber of bed. Down to the discoloration of his teeth, and to the dust on his toe, his Cecco, growing so fast now. Grinning there with his Eagle wings, not waxen wings, but feathers once in flight, the fitting stage-prop for his Roman and tenebrist Cupid in jubilation, swooping on dark wings. One could almost perceive his feral scent from the image.

But these were the good times, when he was working, grinding, mixing pigments into paint, preparing canvasses, in strain all day holding postures in fixed theatrical poise. In the good times when he was making art, there was labor and love, consistent and meticulous effort sustained with several other apprentices. He and the maestro with them in mad travail over multiple masterpieces.

And now a single masterpiece, that required only the two of them, was in center of his artistic aims: Love in Victory over all Worldly Things. And still, grind the pigments, mix the paints, pose and poise.

Most nights he shared a bed with the maestro; at times both too tired to even perpetrate that act which in those days would have been a capital offense on both their parts if accused and tried of it. Capital offense means one where you lose your head, whence the caput, he had just learned that word from the maestro.

In fact, Cecco was proud to feel his growing dominion over the master-painter, and sought to increase it instinctively for his own purposes, and to outshine any other youth or adolescent the maestro might look towards, isolating him from them in favor of his own influence.

Because of One Thing: he wanted to be a painter when grown-up, to have an honest trade and maybe even his own studio dedicated to the pursuit of Beauty and Roman Mythology with Madonnas and saints and things. He was willing to do anything to have his dream, that he'd had since he met the artist and started working. The other street-brats he had had to eke out a living amongst back then used to call his face ugly. Ladies passing through would turn up their noses from him in disgust, as if he were something filthy and vile. Yet the most famous painter in Rome shared his bed only with him for some time now and had eyes for no one else. Even his interest in the Donna Lena, famous courtesan named Maddalena di Paolo Antognetti who modeled for him as well, had been pushed aside, who once had made him jealous and fearful for his position.

He had been a beggar-boy, and thought himself too homely to exercise the ignominious but lucrative trade of bardassa that the other lads with seemingly prettier faces would get involved in, like his pal Gianni Battista. Yet the Maestro da Caravaggio saw something more in him, took him as a servant at ten years old, two years ago now--then made him his model and apprentice, intending to initiate him fully into the art of painting, and eventually, he hoped, of reading Ovid. In the meantime, he would become the Muse responsible for a decade of the painter's output.

However, there was a certain very painful and distressing aspect of this life which only seemed to be getting worse. When he was not working, or when he had completed a great masterpiece and had some money to spend, then he would swagger about the riverside vias, hand to his rapier and dagger in a cocksure way, dressing Cecco up in ruffles and pseudo-fineries more brocaded than not, the two of them lost in a gang of young men, partisans of the Vespucci family, touring tumultuous riverside taverns. Ruffians all, but Michelangelo was the roughest, always "looking for adventure" in cerca di avventura. Dens of cardsharps and thieves, thugs employed by all the main Families were the visitations of these outings, the braggartish Michelangelo always ready to fight or debate. Punish cheaters and insult his enemies.

TAVERN SCENE: Those were places of drinks and cards, tabled 'round with myriad carousers and gamblers. Thick smoke mingled into a miasma of wine-pickled breath, multiplied clink of glasses grounded by the shuffle of cards.

Dressed the boy to look smart, but still he felt overwhelmed there in this noisy place, even before any sign of danger. Brought back bad memories. Couldn't he wear nice clothes in a better place? Such loud voices and ruckus--almost worse than the strife of the street. Den of thieves and assassins, why would he continue to bring him to such places?

But the maestro said that this experience was as essential for his art as the rest: all of these outcast and ruffian sorts (while reminding him of himself) furnished the very faces and bodies of saintly figures, as Christ himself sat among the downtrodden and sinful, the harlots and the thieves. This was the birth of the first idea of a painting. The common folk were the vehicle for the Redemption of Christ, prototype of the lives of the saints. But so often the Church rejected his vision and urged him to modify his works.

Easy to say. When later that evening, considerably drunker at another establishment, a man from the Tommasoni family, glaring furiously at Cecco, called him a stinking street-rot of a bardassa and that Dog of Caravaggio had better beware lest his pup leave him for a higher-paying customer. The maestro leapt forth, drawing his dagger before anyone could stop him, overturning the table. Pinning the man's head to the ground, he cut off most of the man's ear, right there before Cecco, shouting in a drunken rage:

"Are you paid by Giovanni Baglione to defame me?!" repeatedly until they pulled him away from the wounded man.

Cecco cried that night: he was horrified and flattered at the same time, violated yet protected.

Back to MID-POSE

"Maestro?"

"Yes, Cecco?"

"I'm still holding the pose; did you know that?"

"Yes, bambino, I knew that. Now keep still, just a little bit longer."

"Maestro, you know Giovanni Baglione? and his goons, and all the things they say about us?"

"They want to ruin me."

"Anyway, I was in the church the other day to look at the pictures and saw what he had done. I just want you to know, I think he's a really bad painter. It all looks fake even though he tries to copy you."

He paused his work.

"Thanks Cecco."

***

CRITIQUE:

LUIGI VESPUCCI: In this new painting by Caravaggio, we see a life-sized Cupid after a boy of about twelve who bears large brown eagle wings, painted with such lifelike precision and such strong coloring, purity, and sculptural relief, that it all comes to life.

THE ENGLISH AMBASSADOR: It is ye bodie and face of his owen boy or servant that layd with him.

GIOVANNI BAGLIONE: I for my part can't stand the sight of that brat; the look of his smirk in that savagely sinful painting just makes my blood boil--as if fresh from the unfortunate bed of lust he's been debauched into. This comes from a man whose thoughts are far from God.

LUIGI VESPUCCI: Nevertheless, you base your whole critique on an ad hominem attack. The disinterested Spectator looking at the painting can only wonder where the wings came from. Were they invented? Were they a prop? Or did the youngster himself actually possess wings?

GIOVANNI BAGLIONE: The Spectator looking at the painting can only wonder how a grimy-footed furrow-faced urchin grinning inanely like that could be considered a fitting representation of the Roman God Cupid. Frankly, we expected more from the infamous Maestro da Caravaggio. It is quite as believable as his semi-clad adolescents are believable as Angels, and quite as foul in the eyes of the Lord! These are borrowed eagle's wings he hoped to fly on, and were indeed wings of wax. The same heathen wings that seized the prehistoric Trojan lad all a-weeping from his mother in fierce talons, to go and make him his cup-bearer.

THE SCOTTISH AMBASSADOR: Zit it is worthie remembrance with quhat dexteritie he red himself of the handis of thame that at that tyme detenit oure persoun captive.

LUIGI VESPUCCI: True. Well said, my dear friend and unlikely ally--

GIOVANNI BAGLIONE: Really now. Lie down with dogs and get their fleas, I suppose...I ask you, what about The Conversion of Saint Paul? He gives us a horse's ASS, instead of Saint Paul!

[CRITIQUE: The English and Scottish Ambassadors' words unfortunately give way to the venomous vendetta and vitriol of the Virtuous Giovanni Baglione, rival Artist, fellow Shadowist, copycat par excellence. Until:]

MICHELANGELO MERISI DA CARAVAGGIO: (emerging from behind the curtain) You dare mock my horse's ass!

And yet--

it stands in God's light!

***

IN CERCA D'AVVENTURA

A couple of years spiraled by; the painting Amor Vincit Omnia had been sold (not for the price it merited) to a certain rich cardinal who destined it to decorate his antechamber; neither Francesco nor Michelangelo Merisi would ever see it again.

It would have been hard to say if anything had changed. The maestro was as quick and uncompromising with his dashing brush as ever; he was also as touchy, provocative, and quick to strut or pick fights about town with that same brutal sensitivity as before. Cecco's devotion to the Artist and to his own painterly ambitions had only increased: in the full throes of his adolescent passions, soon but not yet, he would begin to call his lover Michelangelo instead of Maestro. He collaborated, albeit to a minor degree, in many of his paintings: doing washes and reinforcing outlines--helping with the coloration. He had begun to compose his own tableaux. They were Still-Lives, mainly, in concentration on simple flowers and fruit right now. The maestro had told Cecco how for him, it had all begun with painting Fruit. And much the maestro had accomplished, painting fruits then painting boys--now painting saints.

So Cecco painted his fruits and flowers with mounting dexterity, but a boy or a sainted Madonna is a very hard thing to paint. So he stuck to fruit (for now). The maestro showed great pleasure in his improvements as well as great assiduity himself in his pupil's instruction.

They even traveled to the great city of Florence together during the holy week of Easter; the maestro wished him so see what he called the True Classics of Italy, so much less numerous in Rome.

"It will be a good influence for our craft, caro bambino, for the both of us."

The sight of all the Quattrocento masterworks delighted the fourteen-year-old beyond measure, and they sketched ancient and modern sculptures together from life in the grand arcaded galleries.

Certainly this fulfillment along with all the love the boy could offer would have been enough adventure for a restless soul. But no, adventure always had to be sought anew, and always he was off to those riverside taverns in Rome, and his incoherent muttering about "that jabbering Giovanni's vendetta" which somehow always was valorized in the face of the public. But Maestro da Caravaggio produced enough of his own defamatory propaganda. How many nights he was arrested for brawling, and Cecco, sometimes locked out of the studio, would have to wander and scrounge until that scoundrel was back out of jail. From tavern to tavern, more and more loosened, staggering not swaggering, bruised and bloodied. Getting sued by a tavern waiter for having cast a plate of artichokes in his face, charges pressed for beating up a police officer, that sort of thing. Cecco himself would be lucky to return unscathed by this exhausting recreation, this tiring game of shadows and light. To be trailed along like that, dragged-out, kept in tow, even on display in those fine clothes, only to go and wallow in the muck, was simply more than he could bear at times.

Thus Francesco had ceased really to accompany him on these escapades, would just refuse (sometimes berate him) and simply waited for him to return. The long and lonely vigils petrified in fear of the worst, unable to even practice his painting for lack of light. For, what reason did he have to make him suffer such tragic martyrdom--as if fueling the emotive play-acting they did before the canvass?

However, worst of all was when Michelangelo returned home, to be yelled and screamed at in his strange jealousies and rageful fits, disassembling phrases in a final delirium before finally fading into unconsciousness. When he had made Cecco weep bitter tears with his brutal shouting, Michelangelo would find him curled up asleep on the stones by the hearth in the morning, and not in his bed. Then he would know he had some excess to atone for. Thus, contrite, he cajoled and showered him with pet-names and gallant little humilities, himself weeping as he thought of his cruelty.

But then, more taverns and cardsharps and billiards, always with wine and more and more wine, until the world was nothing but wine and blood-brawls. Yet, although he was a man who would fight, mutilate, maybe even kill over a card-game, he never would strike the youngster; even in drunkenness, he spared Cecco the direct blows so copiously dealt elsewhere. They craved each other madly but things were changing into a new form of sameness. Still, this was not the path to a steady life, but to gradual derangement. Nothing good was going to come of this; he feared some tragic outcome.

Until Inspiration would strike.

Of course It was there, even in the low life of the riverside, the incarnation of divine figures, otherwise how would the two of them ever have met?

So then in the fury of the moment's creative impulses, the wine and the street-life wasn't so important anymore, love and labor was enough living for art.

[productive times followed by] CATASTOPHE

A year. How long? Two? have passed. He's killed a man! out again on one of his grand adventures. Per un fottuto gioco di carte! over a fucking card game! The scoundrel, how many times have I told him?! He had accepted a duel on the Campo Marzio with that cut-throat gangster Ranuccio Tommasoni over a fucking game of cards! (at least he won, both the duel and the card-game, of course I knew he would): pursued, going into exile, he will make daring escapes, I wager. He wants me to go with him, he begged me. I won't. I can't go with him. I will grow up now, I must make my own paintings and go my own way, far away from his anguish and delirium. I must find the wings, to take life's flight. Although I know now, after seeing him paint for years, that I'll never have the genius of the great Caravaggio, but I know one day I can have my own studio and transmit his Way to Posterity, if now I avoid his darkness and separate myself from his doom. Still, he has imprinted the nature of his work upon me: I will always paint from life, I will always be a Shadowist, I will embrace the order of chaos and the fire of Cupid, ever burning. My saints and Madonnas will be modeled from the downtrodden and sinful of the city, showing every strange cast of contrast. And I will never throw myself away over a stupid game of cards or jug of wine.

FINALE: CHAOS AND CUPID

[This winged cupid is not painted blind] he has: taken FLIGHT--

out of the chaotic tumble of a broken still-life, coalesced from an oily swirl of solid darkness, that in which Cecco would be immortalized: just as he was in those days, holding his pose for all to see. When they were both long dead in ages to come, Cecco would still be grinning his cheeky overdimpled grin, made safe against the ravages of time, truly protected from this most voracious of Enemies. The Artist hadn't wanted some hollow-eyed statue or porcelain doll, but the Absolute Reality of Cecco's own saucy and scrunched up smile, making the place almost echo with his triumphant laughter. Whatever it might have been, and however anyone might judge it, It would be seen. It was there in the roles of innumerable angels, saints, and of course conquered in the supremacy of Cupid's motto from Virgil's Eclogae,

like a title tacked on at the end:

OMNIA VINCIT AMOR ET NOS CEDAMUS AMORI

[love conquers all, let us too yield to love]

A Tableau that could represent the density of CHAOS and NIGHT in the flash of light much like the illumination of a thunderbolt [the golden and the leaden arrows]: an arrow of flame.

COSMIC CUPID--a universal chord trampled on the instruments, allegorically triumphant.

Chaos was the first being, the prime power. Then arose mighty Terra, the great earth and Mother; Cupido then came forth, surpassing every other immortal in beauty, limb-loosener, he brings mortals and immortals under his victorious might, rendering them unable to think. Due to his binding force--uniting opposites--Night and Day/Light and Darkness, were born from these primordial beings.

Chaos never vanishes, much less Cupid the vanquisher: his wingspan is measureless, and his flight is swift. Our labors cannot change him, nor can armor protect us from his arrows. No science or art can rob him of his mystique, here represented in painted prose on borrowed wings:

Love vanquishes everything/

let us all surrender to Love.

About the Creator

Rob Angeli

sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt

There are tears of things, and mortal objects touch the mind.

-Virgil Aeneid I.462

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insights

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Excellent storytelling

Original narrative & well developed characters

Compelling and original writing

Creative use of language & vocab

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

Masterful proofreading

Zero grammar & spelling mistakes

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

Comments (21)

You are a marvellous art historian! I learned much in reading your work, about society, the artists, and humanity. Your expression of thoughts allows for an easy and pleasureable read. Congratulations on having your work recognized!!!!

This was a wonderful read. The way the art is incorporated into the story really takes me to the time period and feels relatable in many instances.

First impressions of your writing style: simply beautiful. You write in a sophisticated manner, gathering trust in your story, which is already woven with strands of fiction and fact. I love this state of ambiguity. Of course this is art history, but there are strands of fancy, which only add to the experience and beauty. I love it all mixed together. Such vibrancy in the past from your view, and it shines through magnificently. Your choice to transition in and out of the story’s headings, including them as sentences, is just so fun. In particular, I love the "Dialogue [begins]:" heading. It reads like journal entries, historical accounts, prose poetry, even a play at times; a wild read, but controlled so well. (Ongoing praise as I read): What a clever way to teach about this painting, to frame it in a story that reads as a genuine tale, not a lesson (you know the ones I mean, they read like math word problems?). And the dialogue reads so organically, between maestro and pupil; just a wonderful way to characterize them and teach us (thru Cecco!) simultaneously. I LOVE chiaroscuro. Was obsessed with it in college and my husband did some paintings using the technique, which turned out awesome. That paragraph where you describe Cecco’s appearance is so well written. I adore how you went about painting him with words, this man’s muse. "…with all the grunge of the Roman street and of the art workshop--just as he knew him even awakening from the slumber of bed." The whole paragraph is gorgeous. The maiming scene and the conversation that follows is so gripping. Absolutely loved those sections. LOVE the critique part. You’re so creative to do it like this, bringing in the various critics to argue over what’s important to focus on when judging an art piece. Do you bring in the artist’s personal life or simply focus on the paint on canvas? Well, see this debate not get resolved! Such an important thing to consider, though. The humor at "horse’s ass" has me rolling! The metaphor here is stunning: "And much the maestro had accomplished, painting fruits then painting boys--now painting saints." "They craved each other madly but things were changing into a new form of sameness. Still, this was not the path to a steady life, but to gradual derangement. Nothing good was going to come of this; he feared some tragic outcome." Wow, the way you describe their relationship is so emotionally fraught. It’s heartbreaking. Startling ending. Absolutely wonderful work! Was it an entry in the painted prose challenge? It should have placed. My goodness, truly well done. ❤️👏🏻 Some minor critiques (Please feel free to skip this part, if it isn’t what you’re looking for from me, lol! I won’t be offended. I only wanted to support you in more ways than the well-deserved praise.) * "metamorphormed" is not the past perfect form of the word, but rather "metamorphosed." (loc. "Si, she asked the river-god to rescue her. And he did. She was metamorphormed right then and there into a Tree.") It’s possible you meant Cecco to say it this way to demonstrate his humble origins, but I’d expect Caravaggio to address it, since he’s been correcting him in this very conversation. * Typo of 'canvas' (you use 'canvass' (loc.: paragraph 3 after "Wingspan of the Brush"). "Canvass" means something else. And 'canvases' is the correct plural form. * "Because of One Thing:" I feel this was meant to be bolded as a heading.

Top story, indeed! Of course! The sheer technicolor of your writing takes my breath away. Thank you.

Oh, R! You have such an extraordinary talent for bringing life and light to historical figures and really humanizing them. The way you wove Caravaggio's works into the story was brilliant, and the pain and ultimate triumph of Cecco's life was so relatable. Truly an incredible piece ❤️

Your writing and the accompanying art bring much to the reader! I appreciate the art history and research, as well as deeper insight into how the expression of art is criticized by the audience and the artist.Congratulations on a well-crafted and insightful story.

Wow! This was truly an experience to read! What an incredible story you told here– delightful, suspenseful, engaging! Fantastic job– you are a very talented writer! I enjoyed this so much. Congrats on top story– Very well deserved!

Congratulations on Top Story! Good one

Congratulations on Top Story!

Congratulations on Top Story!❤❤❤

Congratulations on your Top Story

This comment has been deleted

Congratulations on your Top STory

Enjoyed the viewpoint

Am a reader I want to make money while reading please help me out 🙏

Oh YAY! Congratulations on the Top Story!!!!!!

This felt like rushing down a River on a raft- exhilarating, dangerous, bracing- and out of my control. Thank you for making this so relatable and real- what amazing talent.

This was incredible. So informative in the most creative way. I will be recommending you for top story on discord. Thank you for your comments on my work and for sharing this piece with me to read. I loved every second of it.

This is amazing and thoroughly educational, I will come back here again to absorb some more details.

Some amazing pictures and great insights. I assume this is for the Painted Prose challenge and is definitely deserving of a Top Sory. If you are on Facebook please join us in The Vocal Social Society

reso in modo unico e vivido. ben fatto // uniquely and vividly rendered. well done

Outstanding! I love love love this piece.