Content warning

This story may contain sensitive material or discuss topics that some readers may find distressing. Reader discretion is advised. The views and opinions expressed in this story are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Vocal.

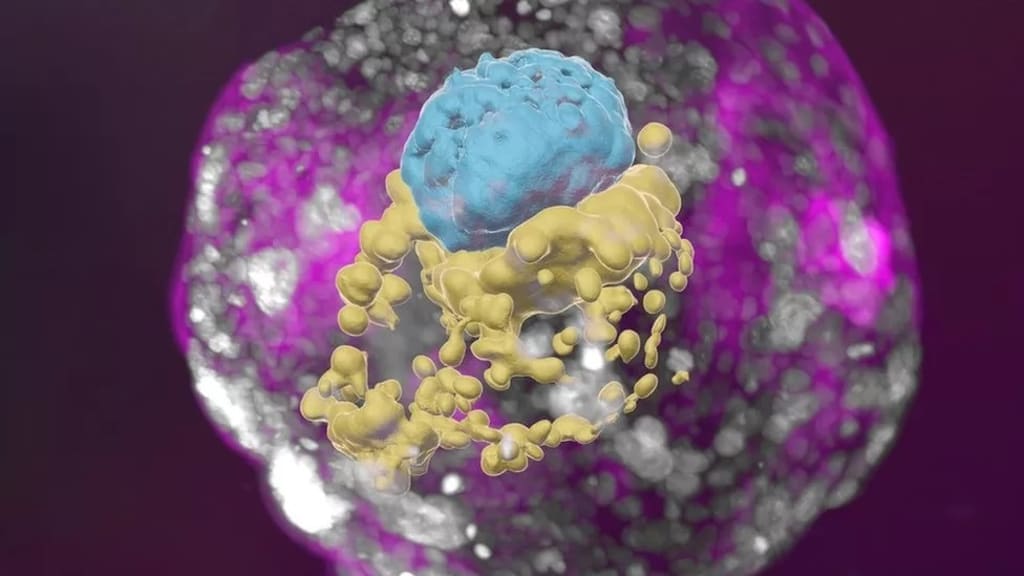

Scientists grow whole model of human embryo from stem cells?

Scientists grow whole model of human embryo from stem cells

Scientists have developed an entity that mimics an early human embryo without using sperm, eggs, or a womb.

According to the Weizmann Institute researchers, its "embryo model" created using stem cells looks like a classic example of a real 14-day-old embryo.

It even released hormones that made a pregnancy test in the lab positive.

The goal of embryo models is to provide an ethical framework for understanding the early stages of human life.

The first few weeks after a sperm fertilises an egg are a time of tremendous transformation, from a collection of unclear cells to something that may be seen on a baby ultrasound.

This critical period is a major cause of miscarriage and birth abnormalities, yet it is little understood.

"It's a black box and that's not a cliche - our knowledge is very limited," Prof Jacob Hanna, from the Weizmann Institute of Science, tells me.

Starting material

Embryo research is complicated legally, ethically, and technically. However, there is currently a fast growing field that mimics natural embryo development.

The Israeli team describes this study, which was published in the journal Nature, as the first "complete" embryo model for imitating all of the main components that arise in the early embryo.

"This is a textbook image of a human day-14 embryo," Prof Hanna adds, adding that "this hasn't been done before."

Instead of sperm and eggs, naive stem cells were used as the beginning material, and they were reprogrammed to have the ability to form any sort of tissue in the body.

Chemicals were then used to coax these stem cells into becoming four types of cell found in the earliest stages of the human embryo:

epiblast cells, which become the embryo proper (or foetus)

trophoblast cells, which become the placenta

hypoblast cells, which become the supportive yolk sac

extraembryonic mesoderm cells

A total of 120 of these cells were mixed in a precise ratio - and then, the scientists step back and watch.

About 1% of the mixture began the journey of spontaneously assembling themselves into a structure that resembles, but is not identical to, a human embryo.

"I give great credit to the cells - you have to bring the right mix and have the right environment and it just takes off," Prof Hanna says. "That's an amazing phenomenon."

The embryo models were allowed to grow and develop until they were comparable to an embryo 14 days after fertilisation. In many countries, this is the legal cut-off for normal embryo research.

Despite the late-night video call, I can hear the passion as Prof Hanna gives me a 3D tour of the "exquisitely fine architecture" of the embryo model.

I can see the trophoblast, which would normally become the placenta, enveloping the embryo. And it includes the cavities - called lacuna - that fill with the mother's blood to transfer nutrients to the baby.

There is a yolk sac, which has some of the roles of the liver and kidneys, and a bilaminar embryonic disc - one of the key hallmarks of this stage of embryo development.

'Making sense'

The hope is embryo models can help scientists explain how different types of cell emerge, witness the earliest steps in building the body's organs or understand inherited or genetic diseases.

Already, this study shows other parts of the embryo will not form unless the early placenta cells can surround it.

There is even talk of improving in vitro fertilisation (IVF) success rates by helping to understand why some embryos fail or using the models to test whether medicines are safe during pregnancy.

Legally distinct

The work also raises the question of whether embryo development could be mimicked past the 14-day stage.

This would not be illegal, even in the UK, as embryo models are legally distinct from embryos.

"Some will welcome this - but others won't like it," Prof Lovell-Badge says.

And the closer these models come to an actual embryo, the more ethical questions they raise.

The researchers stress it would be unethical, illegal and actually impossible to achieve a pregnancy using these embryo models - assembling the 120 cells together goes beyond the point an embryo could successfully implant into the lining of the womb.

#Science #stem cells # human embryo

Thanks 👍 All

About the Creator

Angel Malaika

hi i am angel malaika🤞 i love to write especially about technology i love to write in class i am 18 yrs old i have failed in school everyone please pray for me and subscribe my account and my posts friends Thank you all for sharing ❤️❣️

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.