Breaking the ice

“One day I will find the right words, and they will be simple.”

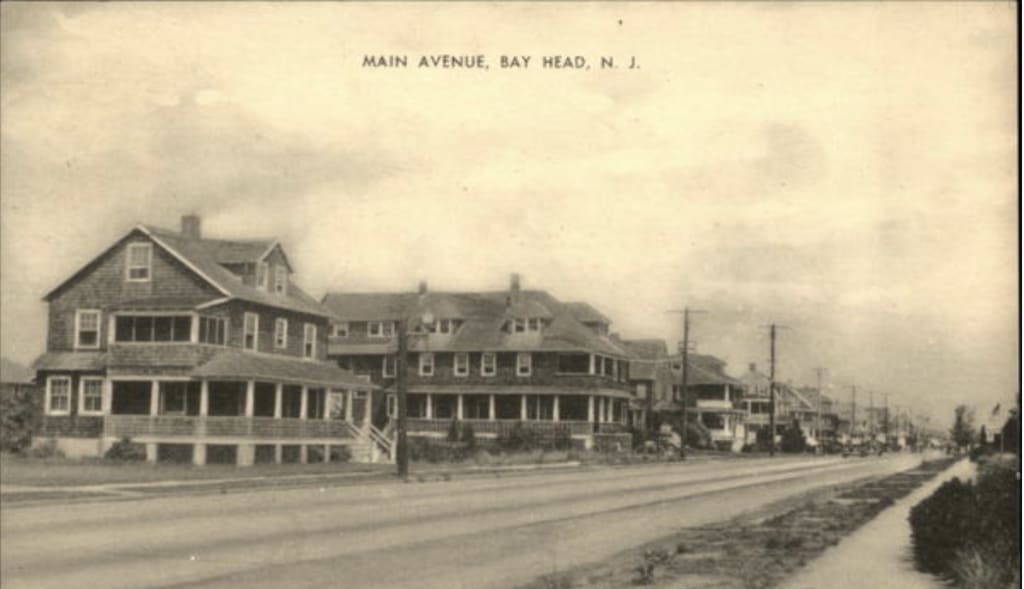

I was a contrarian as a schoolboy. I hated to do what I was told. And in school, I was often told to write. So, I hated writing. After I left school, I took a gap year before I went to university. That winter, I lived in a vacation town on the Jersey Shore. Back then, people observed the seasonal landmarks. After Labor Day, the town was almost deserted.

Tradesmen winterized the large one-season, shingle-style homes. They boarded up windows and drained the plumbing to prevent ice breaks in copper pipes. By January, snow covered the beaches, and the oily Atlantic waters heaved under grey-clouded skies.

One bar in town stayed open, probably more from habit than the expectation of profit. And the few patrons, I was one, chatted about this and that, sitting on a motley collection of old plush furniture that smelled of summer storage. A cast-iron, pot-bellied stove installed for the winter radiated a fierce heat that dissipated within a few feet of the source.

My parents owned one of those homes. A previous owner had made it so the back of the first floor - comprising the kitchen, a sitting room, a bathroom, and one bedroom - could be shut off from the rest of the rambling structure and heated.

It was before the internet. I had a radio but no TV. Fortunately, the house was book-stuffed. Mostly summer reading - but decades of previous families and their friends had left behind a respectable stash of literature. A few miles inland, a year-round town had a library. I also had paper, a box of pencils, and a pair of fountain pens - a writing instrument my English boarding school mandated, as gentlemen did not use ballpoints.

I did not know that I was going to write. It never occurred to me - despite my mother suggesting I try it. The pencils and paper were for doodling. However, I thought I would take a crack at it. So I wrote an essay, “Why it is wrong to legislate morals.”

I wish I could tell you it was a towering work of staggering genius. But I cannot remember if it was any good - not that I recall it being bad. My point was brilliant - you cannot legislate morality. However, how well I arrived at my conclusion is lost to memory. And I never showed it to anyone. What has not left me is the profound pleasure I found in the act of writing.

I mentioned the fountain pens because that was part of the joy of the experience. I did not know how to type or even own a typewriter. Home computers had just started to make their mark, while word processing was the province of business and early adopters. And despite being 18, I was not one of those.

A good fountain pen weighs little but has heft in your hand. It cannot be too skinny. And it must be made of metal. The most important part is the nib. It must be gold, preferably 18-karat. If it is less pure, unseen serrations will cause an almost imperceptible drag that distracts from its operation. If purer, the gold will wear away too quickly. And I was not financially positioned to be profligate. Lastly, I preferred a medium point and blue/black ink.

I was excited to write. It was a new experience for me to say something original. My schooling required me to study books to regurgitate information others had written. The emphasis was more on content and organization than individual style. I had an advantage - although I did not realize it then. I was lazy, as well as being contrary.

To explain how this worked in my favor, I need to give a synopsis of academic testing in England at the time. During the last two years of high school, the curriculum restricted students to three subjects. We did not have GPAs. The scholastic finish line was the A-level exam, a nationally administered affair taken in the penultimate month of the final year. Each exam consisted of three, 3-hour long tests.

My subjects were English Literature, History, and Economics. I should have preferred to take sciences because they did not require as much writing, but I had no aptitude. Worse, those questions required the “right” answer. My exams were essay-based - except for one in economics that tested math skills.

The beauty of essays is that they do not restrict the test-taker to the definitive right/wrong calculation. Examiners mark on a sliding scale. I hoped I could show enough ability to walk away with passing grades. To my surprise, I did better than that. Years later, I still hear my lisping House Master hand me my results with an incredulous “Griffin, a scholar? Who would have guessed.”

To be clear, I was not at the top of the class. And my reviewer was being wry. I had just outperformed expectations. I think I know why. Let me explain.

While every testee received an individual score, the testing authority gave the school a review of how the student body had done as a whole. My school’s report indicated that, while the boys (it was a single-sex school) showed they knew the material in immense detail (it was a good school), their eagerness to get down as many facts as possible precluded originality.

I, swimming against the tide, did not know many facts - as stated above, I was lazy - so I had to throw what few I did into the pot, regardless of how responsive they were to the question. This paucity of knowledge also meant I had to fill in many gaps. And all I had was imagination. I think my scores reflected the fact I wrote conclusions the examiners had never read rather than any ability I had. It also meant that I had some skill to tie together what might appear to be unrelated items.

This unanticipated success made me wonder if I might not have some aptitude for writing. And this is how I came to explain, to a readership of one, why I thought the government had no business legislating morals. I took some things I remembered about the Greeks, some stuff from the Continental Rationalists, a few ideas from the British Empiricists, and a smattering of newer philosophies and threw it all into the mix.

At this point, the reader might think I pursued a “baffle them with bullshit” strategy. I did not, mainly because there was no “them.” In addition to being contrary and lazy, I was also shy. The idea I would show my writing to someone else was inconceivable. The exercise was exclusively for my own enjoyment. And to see if I could support with argument what I knew intuitively to be true.

We all like to be right. And most of us have opinions. But how do you know you are correct and that your views are supportable and coherent? For me, writing gets me closer to that goal. When I say “right”, I do not mean it in the way that 2 + 2 = 4 is correct. I mean, you formulate a position that can be arrived at logically.

In that sense, writing is like preparing for a debate. However, that exercise requires a mastery of facts and statistics, anticipating your opponent’s evidence, and formulating a rebuttal. Writing - at least good writing - has, in addition, an aesthetic goal. George Orwell, who is paradoxically one of the most revered writers in English and yet underestimated as a craftsman, said:

“What I have most wanted to do throughout the past ten years is to make political writing into an art. My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice. When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, “I am going to produce a work of art.” I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing. But I could not do the work of writing a book, or even a long magazine article if it were not also an aesthetic experience.”

That is how I felt after I wrote my first piece. Thousands of political essays later, I still feel the same. Not that I knew that beforehand.

I wanted to make a point. I did not know how much pleasure I would have in crafting the words to make that point. I cannot draw or paint. I do not sing well. I enjoy movies immensely - but that is someone else’s art. My sole creative outlet, if you do not count being moderately entertaining at cocktail parties, is writing - both fiction and non-fiction.

Why did I pick the government legislating morality as the subject of my first attempt at non-scholastic writing? I do not remember. It must have sprung from a fourth aspect of my personality - beyond laziness, shyness, and contrarianism - my mistrust of people in authority. I was eighteen, as I said, and anti-establishmentarianism was part of my job description.

As I put words to paper, I discovered that writing is hard. I tossed out some sentences and then a few paragraphs. I was rather pleased with myself. Then I reread them. I had generated a mess of fancy words and pretentious phrases that even I found boring. I compounded my ineptitude with more of the same with the belief that a sesquipedalian vocabulary could paper over the tedium of my prose. That was my real baffle them with bullshit phase.

I despaired. But there was little else to do until the cocktail hour, so I kept working away. I cut out words like sesquipedalian (until I just used it twice to make a point). I stopped rewriting the first four paragraphs - and started putting down my ideas without agonizing over every sentence at its finish.

It was still pretty bad. But it was complete. It was then that I realized the key to writing as well as I was able, lay in the editing. So I started writing drafts in pencil because the critical tool in saying what I wanted to say was an eraser.

I knew I had finished when sometime later - I cannot remember if it was hours or days - I had maybe 1,000 words that, had someone read them, I would not have been mortified. Not that I solicited a reader. That would have to wait a few years.

In some ways, I have not changed much as a writer - at least in my interests. I could still write an essay about why the government should not legislate morals. It would be interesting to compare a piece today with the one I wrote then. Except those pieces of paper are long gone, and I cannot remember a single sentence I wrote.

This ignorance is my burden. I admire and am astounded by authors who can quote at will from any part of their canon. I have trouble remembering what I wrote yesterday. Fortunately, my more recent stuff is in the cloud. I can therefore reread it at my leisure and learn something new when I do.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.