Raiders of the Lost Creek

The archaeologist, the Mayor, original Las Vegas, and the showdown that created the Springs Preserve

In July of 2007, The Las Vegas Springs Preserve opened for the first time. The public and the press came out in droves. There were big photo ops, a ribbon cutting, lots of politicians and officials smiling for cameras, and speeches. Head of the Las Vegas Valley Water Commission, Pat Mulroy, spoke of saving the Las Vegas Springs, including the original settlement earlier called Big Springs, and congratulating everyone on the continuing construction of the massive complex called the Springs Preserve.

As the crowd dissipated, an elderly couple was motioned by a friend to stand by the sign announcing the opening, for a photo. Not on the guest list, the pair looked a bit reluctant and self conscious, but no one even noticed them. The friend took the photo, and they began to walk away. Pat Mulroy spotted them, excusing herself from an interview, she stepped over to greet them. She looked at the woman and said, "I should have had you speak!"

Over thirty years earlier, that couple had stood on the same spot. But then there was no party, no crowd. It was the mid 1970's and Interstate 95 was soon to be extended west of downtown. Authorities had agreed that the best apparent construction route took the eight-lane freeway right through Big Springs, a critical piece of open land at the Las Vegas Springs. To most onlookers, the place appeared to have little more than a few old cottonwood trees dotting its 180 acres. The land was owned by the Las Vegas Valley Water District, making it easily had, and the plans were laid.

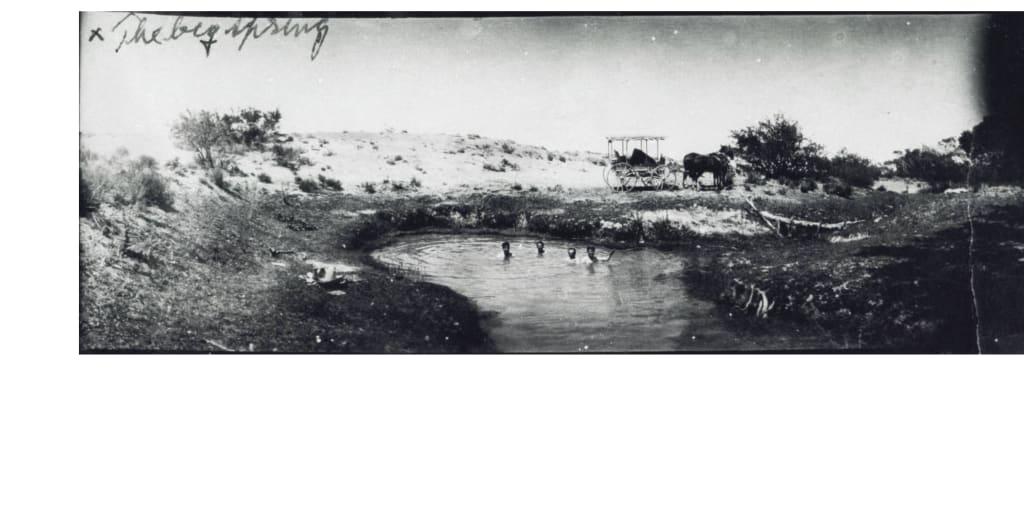

It didn't take long for my mother, preservationist historian Elizabeth von Till Warren, to realize the planned new freeway would run through the site of the first human settlements in the area. This was the namesake location of the original meadows for which Las Vegas is named, where fresh water once burst from the desert floor in artesian pools so powerfully, settlers found that one need not know how to swim, because the pressure would keep you afloat. My father, UNLV Anthropology professor Claude Warren, quickly took action to point out the missed importance of that vacant land. The Warrens were two of the very few experts who had experience on the property, having completed an archaeological survey there in 1972. Mom quickly pulled together a group of other concerned citizens, and they began to speak out as "Friends of Big Springs."

"Dr. Claude Warren of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas conducted an archaeological survey in 1972 that found long-term human occupation of the site.

"His discoveries helped reroute the new Oran K. Gragson Expressway (US 95)"

Fortunately, the freeway was instead curved north, around the site, before heading west. The Warrens also set in motion plans to have the Water District register Las Vegas Springs as an archaeological site with the National Trust for Historic Places, which took place a few years later.

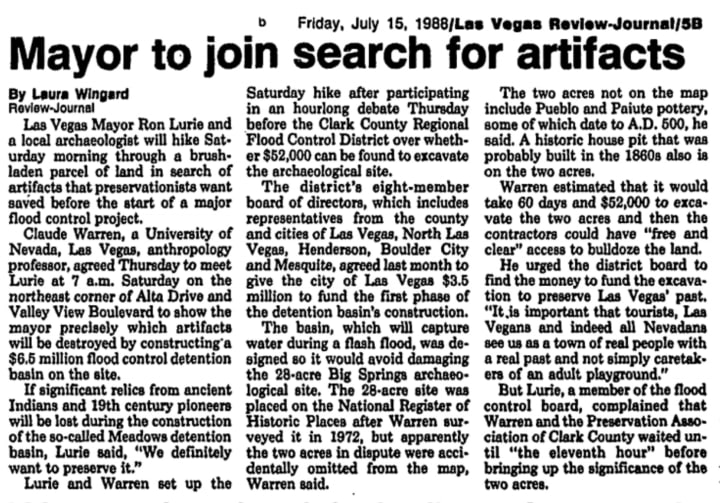

But Preservation is seldom a done deal, and the Las Vegas Springs came up for construction proposal again, ten years later. That's when Las Vegas Mayor Ron Lurie and the City Council approved a flood control basin on another part of the site.

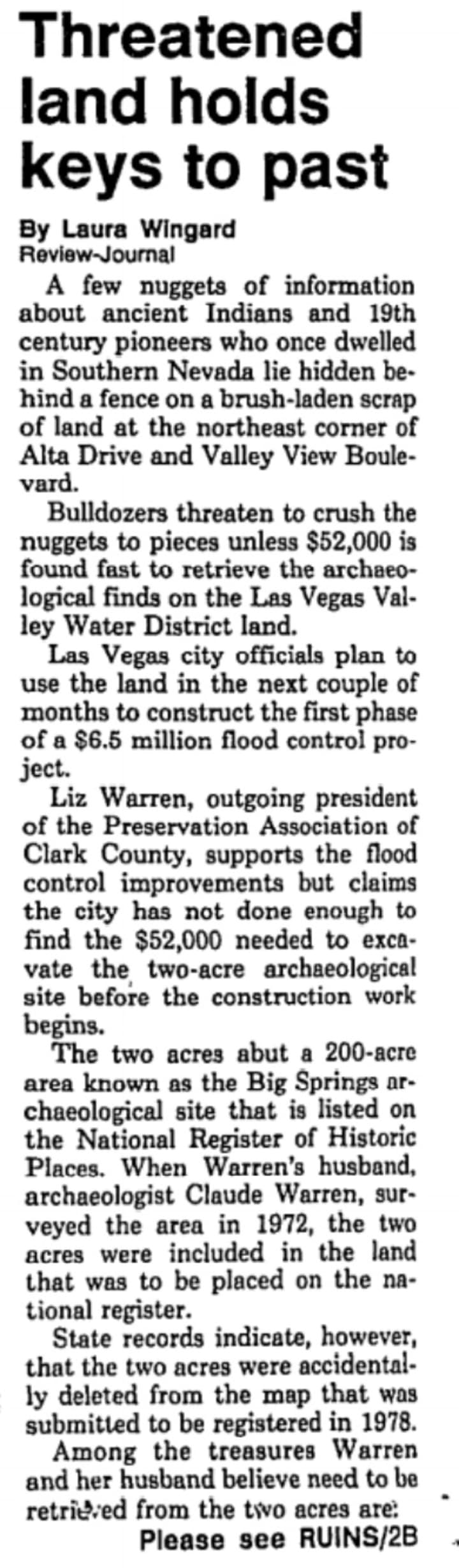

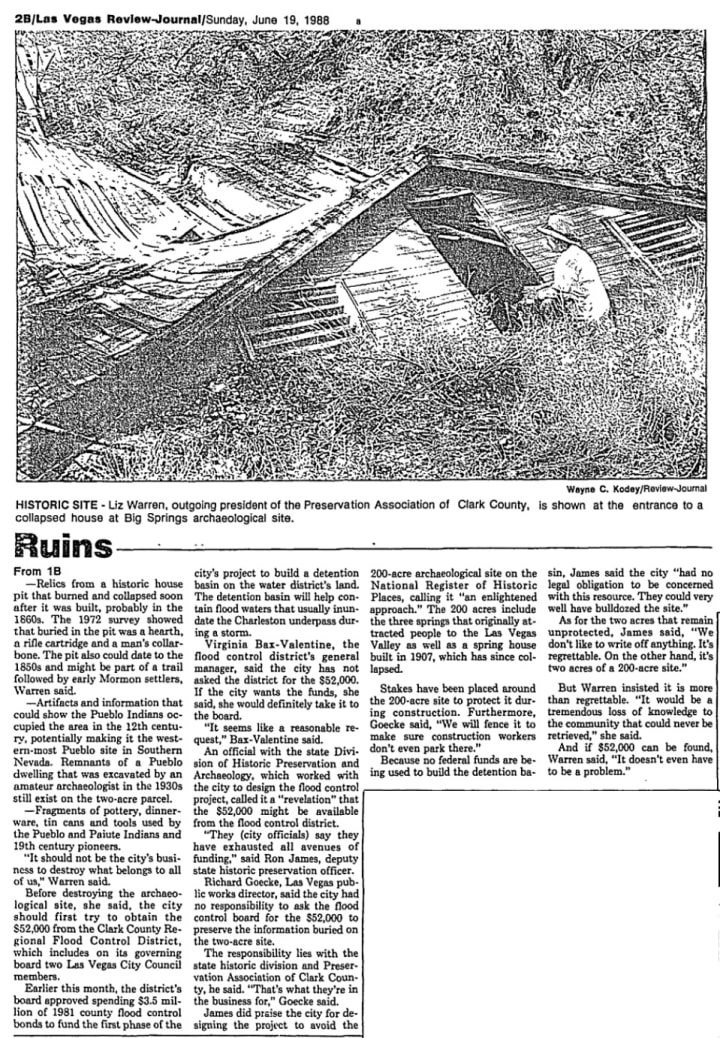

No one argued against flood control, but the choice of site sounded the alarm among preservationists. It turned out that the map used for the filing with the National Trust back in the late 1970's contained a mistake, omitting a critical two acres. These were the very two acres which were the genesis of the name "Las Vegas," Spanish for "The Meadows," The original settlement of the town and once the site of the largest spring. The Warrens again took up the cause, fighting to have the site excavated before construction of the flood control basin would destroy it.

Public comment at city hall heard objection principally from my mother, who was President of the Preservation Association of Clark County. She explained the significance of the site, and why it could not be destroyed until it was first excavated. The Warrens had proposed a new archaeological dig in the specific area to be affected, and assured the Council that they could roll the bulldozers in sixty days if they committed $52,000 to the dig. The Council listened, then ruled in favor of immediate construction of the flood retention basin regardless, citing permits in hand as all they needed to proceed. Public comment was closed, and members of the council were ready to head home.

In the audience at the County Commission hearing was my father Professor Claude N. Warren, Sr, a renowned desert archaeologist who knew extremely well what important features lay at Big Springs. He was probably the premier expert on the resident 8,000-year-old native sites at that time. What little excavation had been done at Big Springs had been done by Dr. Warren and his crew. Watching the politicians ignore his wife's testimony, he couldn't believe it, and he wouldn't have it. The 56-year-old, normally soft-spoken academian, clad in his usual long sleeved button-down shirt with rolled up sleeves, khaki pants and Red Wing field boots, stormed down to the podium, despite public comment having closed.

"Now just hold your horses," He dictated as he got to the podium. He ran his hand over his beard, exasperated. He went on to speak in pointed terms to the Mayor, telling him he could not just obliterate the very archaeological site evidencing the reason Las Vegas exists, without at least recovering and recording what was there. He hammered his points home, as he motioned in the direction of the site, a mile away, and the councilmen and women quietly packed up their things for the day. The session stretched over an hour. It had been a long day for Mayor Lurie, and he was getting exasperated too. Things were getting more and more heated, when the Mayor held up his hand to interrupt Claude, and threw down a challenge: "You show me in person where there's a significant site there, I will move the flood basin."

The place went dead quiet. Dad realized then that the problem was that Lurie had not believed the site existed. This, he knew, was the right problem to have.

Ron Lurie was no bureaucratic paper pusher. As a Las Vegas city councilman he had shown real concern for the city in which he had resided since the late 1950's. As Mayor he had made some genius moves with regard to land use, and was something of a history buff himself. He and Warren were both Democrats, and their values seemed to align more often than not.

For Warren, this was an ideal response. Any experienced field archaeologist or preservationist knows that saving sites often requires getting the decision makers, who are often novices, into the field. If Lurie were to go out to the site, the veteran Archaeologist knew the Mayor would be more likely to move the whole project - an even better outcome. Dad knew he had him: "Name the time."

Lurie: "Saturday morning, 7:00 am."

Warren: "I'll see you there."

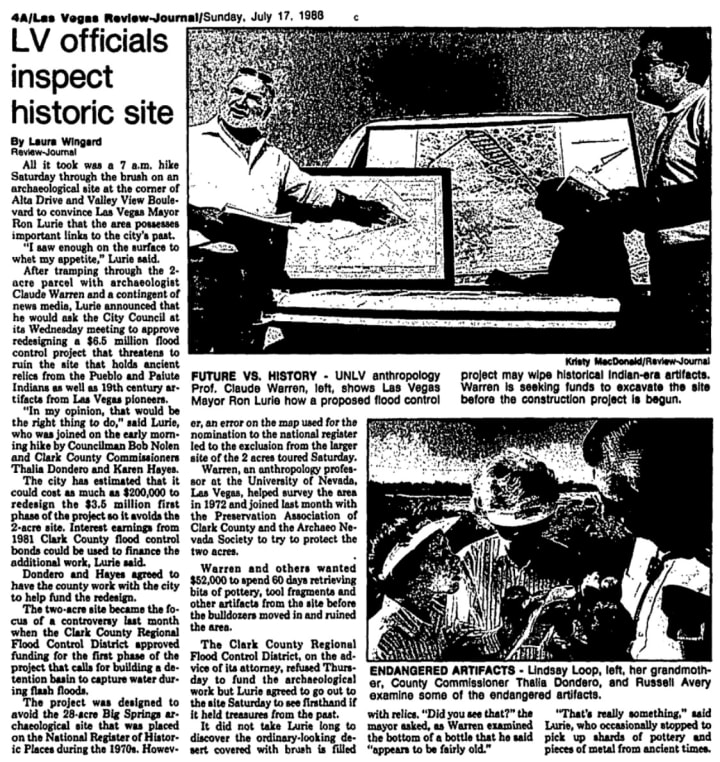

By 6 pm, the standoff was going to press. Liz von Till Warren had told her three adult sons of the extraordinary showdown. By that evening, nearly every student of the popular professor couldn't wait to see what would happen. By the time Mayor Lurie's truck pulled into the water district parking lot at 7:00 am that July morning, the place was packed. Students, preservationists, archaeologists, press, among them my brothers and me.

My siblings and I had seen this kind of thing before. We had been present at digs when my dad's field crew would grab shovels to ward off pot hunters, illegally robbing archaeological sites. Showdowns were not uncommon, and yokels who thought "progress" meant demolition were often jeering from the sidelines. But those instances were usually in remote areas where my father taught field schools. This was literally in the heart of Las Vegas, our home town. We were not going to miss it.

Mayor Lurie climbed out of his truck, looked around at the crowd, then said to my father, "I didn't know you were inviting the whole city." Dad replied, "I didn't invite them. They came on their own."

Contention faded as the beautiful summer morning made for a new attitude, and it was apparent both men loved the desert. Claude asked the spectators to remain behind, and the dueling debaters took only a few members of the press out to the specific two acre site. They returned in twenty minutes. I watched Ron Lurie thank my father, and tell him the site was amazing. He was truly astounded. As he drove away, dad smiled at us. "We did it. He's moving the flood control basin."

Ron Lurie's heart had always been in the right place. It had taken only minutes to see the light, as the artifacts and features were obvious once he was on site with the archaeologist famous in this field. Lurie happily admitted he had been wrong, and excitedly agreed to move the construction of the flood control basin. In the coming days, he did exactly what he said he would do. Las Vegas Springs had been saved for a second time. Ron Lurie went on to be a Mayor known for museum development. He had a lasting, positive impact on Las Vegas.

1997 saw Las Vegas Springs again under threat. This time it was to widen that same stretch of Interstate 95. As there were houses across the Freeway from Big Springs, popular logic had determined it would be much less work, and cheaper, to take the land from the Las Vegas Springs side of the freeway. Once again the site was in danger. And once again, in stepped Liz von Till Warren. When those in power told her it would be too difficult to move the homeowners on the other side of the freeway, she simply replied, "Has anyone asked them?"

"They can have my house," said Cher Blair, who lived on the north side of U.S. 95 near Jones Boulevard.

"Just protect the springs."

Many of the homeowners also jumped at the chance to sell out and move away from the highway noise. The Las Vegas Springs was saved for a third time.

"This is the last best place in Las Vegas," says Elizabeth Warren, president of the Friends of Big Springs committee. Her husband, [Dr. Claude Warren], an archaeologist, excavated the area in 1972.

"In 1978, Big Springs was placed on the National Register of Historic Places after [Warren's] discovery of pottery, arrowheads, and milling stones dating back 8,000 years on part of the site. But the historic designation alone won't save the land [one historian] says.

"Ms. Warren, who has battled for 30 years to preserve the site, agrees. An important factor weighing in the balance, she says, is the story the land has to tell."

In 2001 Liz von Till Warren would complete her PhD dissertation, History of the Las Vegas Springs: A Disappeared Resource, forever exposing the fallacy of what passed for water resource management in early Las Vegas. She remains unsurpassed as the preeminent water historian in the area.

My mother was never particularly fond of the facility created at Las Vegas Springs, called the Springs Preserve. She always felt it was overbuilt, too much "infotainment" and Disneyland, not enough simple appreciation of what the place was. She told me she would much have preferred that it remain open space, more like the visitors center she contributed so much to at the Desert Wetlands Conservancy a few miles downstream. "Central Park," she told me once, "Not Magic Mountain."

"Like gravity and the runoff through the Wash, Liz has always been a "force of nature" herself!"

- Desert Wetlands Conservancy (later the Clark County Wetlands Park)

In an era fueled by ridiculous over-inflation of real estate values, based on "straw" buyers and artificial demand, the Springs Preserve spent $250 million on a facility few could describe. The mash-up of culture, history and amusement park was a passing fad. With ticket prices at about $15, over two million visitors per year were needed in order to take in the minimum required cash flow. It didn't happen. By 2009 the boondoggle had laid off much of its workforce and required $20 million per year in state subsidy. The coming years would see management turnover again and again, and one pursuit after another of any means to financially stabilize the Springs Preserve.

Still, the archaeological sites are protected, and most of the land is open space. The facility, if overbuilt, has its appeal, and grows every year in importance to the community. Overfunding a site, after all, is certainly preferable to underfunding, and some wonderfully devoted staff has evolved there. The facility boasts some incredible views of the city and the property.

So when you sit pondering the open space and historic sites at the Springs Preserve, imagine days gone by, let the buildings melt away and the nearby freeway vanish in your mind's eye. Then contemplate the task of a couple of archaeologists and a ragtag band of concerned citizens of no wealth, convincing the powers that were, to preserve the cultural value of this ancient site, on a large and gorgeous view parcel in the middle of the most visited city in the world. These battles for the history and culture of the area were hard fought for us all.

Contributions from this story support the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation

Take the Warrens' tour of the Springs Preserve

Other writings by Jonathan Warren:

About the Creator

Jonathan Warren

Honorary Consul of Monaco, Chairman of the Liberace Foundation for the Performing and Creative Arts, 50 years in Vegas, Citizen of the world.

www.jonathanwarren.me

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.