My Hometowns

A Walking Tour Through the Soles of My Feet.

I claim more than one hometown, starting with the one handed down to me, the one I had no choice in choosing, but in which I took my first breath. That’s true for all of us until we eventually search out and decide for ourselves if where we lay our heads are hometowns.

We can add hometowns like notches in a gun belt, through luck, good and bad, decisions, good and bad, and a sometimes-unrelenting wanderlust that keeps us on the move while making us pine for the places we’ve left behind.

People say that the eyes are the windows to the soul. But I think it may be our feet instead. I believe that the soles of our feet capture our first meaningful memories. It’s ok if you don’t remember your hometown as a newborn. You probably just laid around eating, pooping, and throwing up when you weren’t rolling around like an awkward little potato sack. Don’t worry, it’s not just you. Babies are like little push brooms, gathering tidbits of life, like old cereal, scraps of paper, and small groupings of God knows what. Maybe they think eating them will imbue their being with a sense of home. But that’s why babies don’t remember being babies.

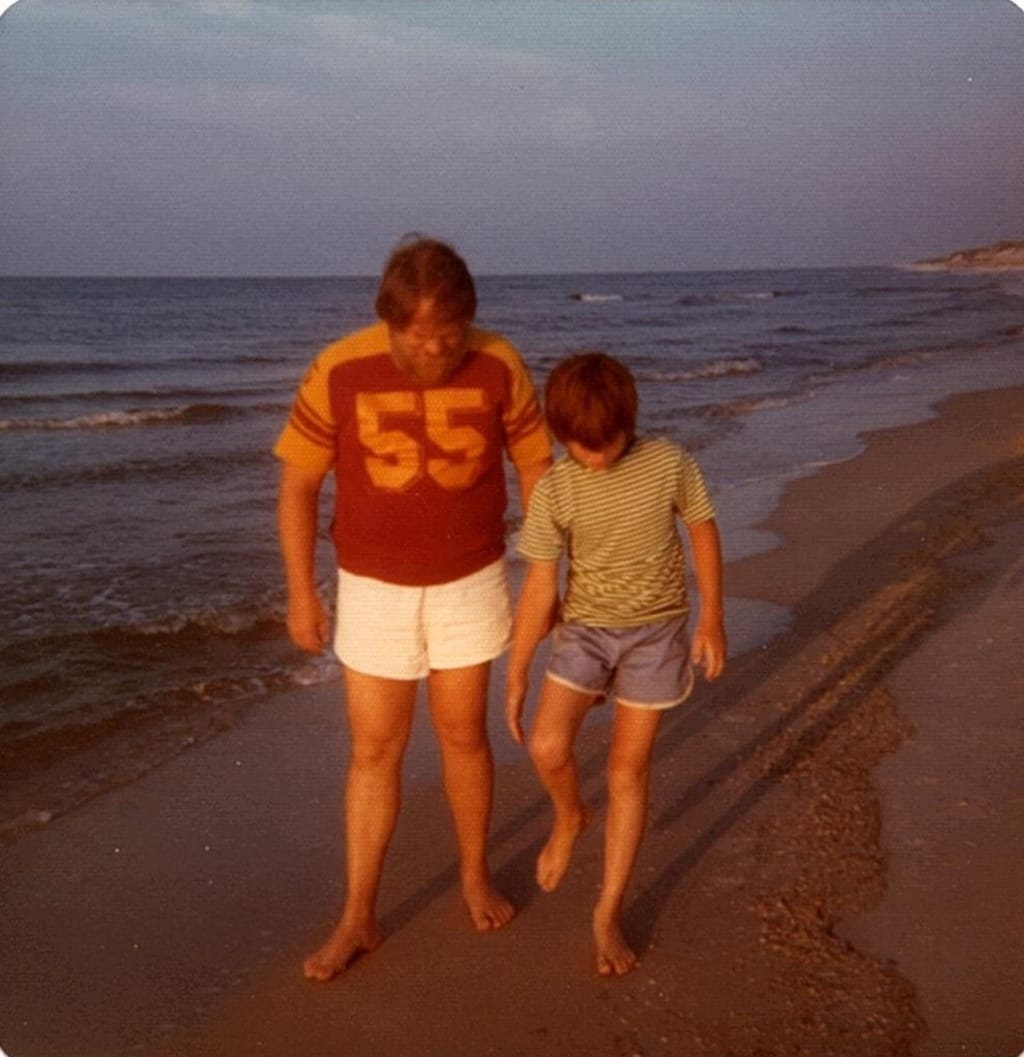

Everything changes once you stand upright long enough to feel the earth beneath your unsteady feet. A sense of home and your greater place in the world sets in. So, to understand my hometown, all of them, one has to see it through the soles of my feet. I have been on the move.

The red clay dust of my southwest Oklahoma birthplace felt like hot, talcum powder floating up through and softly separating my tiny toes. That dirt washed the newness off my feet like water from another time. It was the same red clay ground that bore the steps of the Cherokee, the Chickasaw, the Choctaw, and the other Eastern Woodland tribes of the great removal. I did not know then of the ancient footsteps beneath mine. But I think I felt a belonging that they did not. I know that now because souls pass through soles.

I have muscle memory of brittle blades of Bermuda grass poking against the balls of my feet and the dull-pained pressure from a Nazi soldier’s button in the field across the tracks from my grandparent’s house. The same grown-over wheat field that served as a German prisoner of war camp during World War Two.

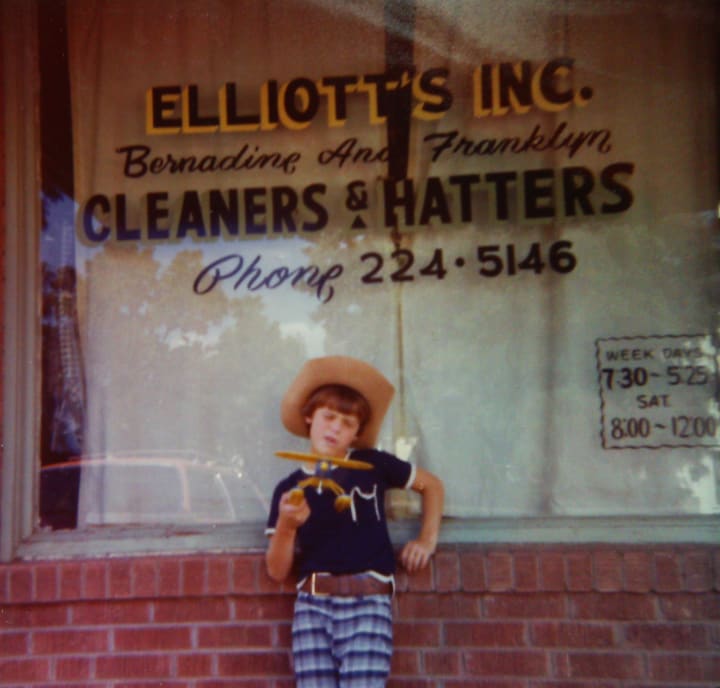

I had become just a summer visitor to my hometown before I began kicking gravel against the back brick of “Elliott’s Cleaners” and stood cooling my bare feet on the smooth linoleum floor in the front parlor, amid steam and freshly ironed clothes. And when my grandparent’s workday was over, I’d play on the small carnival rides at Shannon Springs, once an artesian well along the Chisholm Trail, where cattleman watered their stock as they drove them from Texas farms to Kansas railheads.

It made sense that this Sooner-state city was the horse trailer manufacturing capital of the world for a while. It is a dust bowl-depression survivor and a boom-and-bust town, with oil rigs churning out crude one minute and rusting brown in dying fields the next.

The town changed little between my father’s birth and mine. Kids still laid pennies on the tracks passing by South Sixteenth Street and West Colorado Avenue. And when the big freights rumbled through during the stormy spring, the more inexperienced residents rushed down to the basement. Sometimes it was hard to tell the difference between the Santa Fe on the tracks and the tornados in the fields.

✤ ✤ ✤

By the time I was four years old, I lived twelve hundred miles east of my native Chickasha, Oklahoma. I traded the plains and the shadows of oil wells and Indians for the Appalachians and the silhouettes of coal tipples.

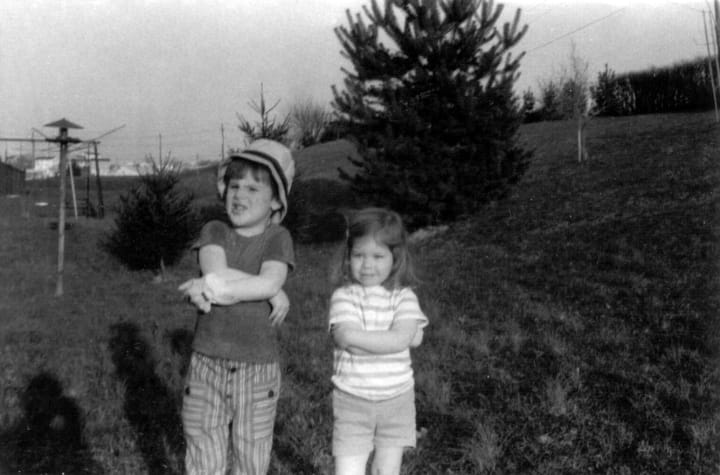

I traipsed the Morgantown hills behind my house and the trails of Cooper’s Rock along the Cheat River Gorge. Dry, fallen magnolia leaves crackled beneath my feet like an October campfire. And over the next few steps, the twinge of maturing ginseng stalks zeroed in on my insoles. Those steps captured my attention. I felt a kinship with that Mountaineer city surrounded by the great highlands. Barely old enough to belong in kindergarten, I felt I belonged along the rocky ridges and river-canyon trails we frequented on weekends. And not unlike my spiritual connection to the five tribes of the Cherokee, the long walks we took through union country connected me with a people I later felt great affection for.

Remember that souls pass through soles.

My parents taught at the School of Social Work at the university. They served as community organizers in the waning war on poverty, meeting in railroad tunnels, darkened hollows, and old mines, far from the spying eyes of those less interested in the rights of workers, women, and children.

I had my hands full with an older woman.

On impulse, I married Rachel, the five-year-old, redheaded firebrand from across the street. So even if I would have understood the politics of mining life, I’m not sure I could have absorbed anything more than a tricycle ride down Lawnview Drive.

On trips to the park, I dangled my feet in the Monongahela river while the older boys pulled bass from its belly. I remember stray chunks of anthracite, streaking black along the sides of my tiny white tennis shoes like a coal-country crayon. It was nineteen seventy-two, and we lived in the heart of Wild and Wonderful West Virginia. What a lucky break. The state is more mountainous per square mile than any other state in the union. If you flattened all its peaks, it’s said that the landmass would eclipse that of Texas. That makes this Oklahoma boy feel prideful.

✤ ✤ ✤

As I kicked off a ripped pair of green and white Chuck Taylor’s and ran down the middle of Starmount, I felt the kindred spirit of my next hometown shoot up through my bare feet like a firecracker.

Though I didn’t know it then, Starmount Drive, in Tallahassee, Florida, ended up being the year of my childhood that most defined my adulthood.

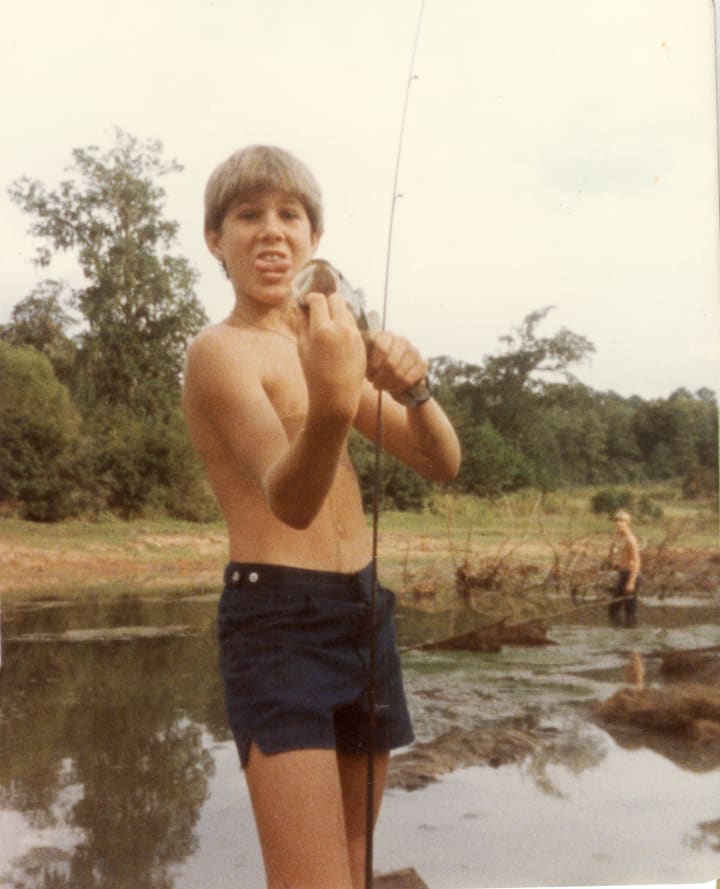

Walking barefoot over pine needles and sweet gumballs, through crawdad creeks, snake thickets, and the occasional Grape Nehi bottlecap, transformed me into a hard-headed, soft-hearted southern boy. An only child no longer walking solo, I fell in love with wilderness, like-minded companions, and ungoverned adventure.

It was 1977, and the spirit of freedom and autonomy I experienced in that time and place felt much like a re-birth. I had friends of my own making. We owned our lives between getting off the school bus on Friday afternoons and returning home by the time the streetlights flickered on Sunday night. In between, we camped out in backyards and back fields, fished the richest bream and bass waters I have ever known, played football, rode skateboards, searched for Bigfoot, and named stars after each other. My feet learned to traverse hot, sticky blacktop, sharp saw grass glades, and alligator waters with precision, all in the shadow of brothers from different mothers.

My family owned a 1972 VW Camper Bus that I later dubbed the “Eight Track with An Engine in Back.”

The singer-songwriters of the decade spilled out of that quadraphonic dreamboat like a magic potion. And with mud-bottom, chigger-chewed feet propped up on the seats, my friends and I sang along with every word in the shrill tones of pre-pubescent boyhood. We already believed we were famous for something, so why not act like big-time singers while waiting to get where we were going?

✤ ✤ ✤

That place and time would, years later, lead me to my final hometown and my living.

By twelve years old, the southern boy found himself in the big city. I spent my teen years in the northern Virginia suburbs just outside of Washington, DC. I traded barefoot days in grass and mud for subway platforms, marble museum floors, and a concrete jungle that seemed just as wild as magnolia hillsides and live oak fields.

I learned quickly to get myself from Falls Church, Virginia, to the Lincoln Memorial, The Washington Monument, and the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, my favorite. I even learned to navigate my own way from DC’s Union Station to New York’s Grand Central station. Having the chance to take ownership in many of my day-to-day travels allowed me to pull street-savvy and arrogant-teen sophistication out of wherever you pull those things out of.

I began my social work studies and music career up and down North Capitol Street, from The Dubliner Bar up to Michigan Avenue and the Catholic University of America, where my dad taught Social Welfare Policy, and ran the Institute for Social Justice.

Streets aren’t mean when you’re nineteen, but looking back, it’s hard to believe I did all I did in some of those neighborhoods - no worse for the wear.

I think rural life makes for the perfect hometown when you are young because you need to feel your place in the world in a slimy, swamp-scum, sunburnt kind of way. But when you are a teenager, the big city is a better hometown.

When you walk the streets of a city like Washington, DC, New York, or Chicago, you realize quickly that you are not the center of the known universe; a syndrome plaguing the personality of a fourteen or fifteen-year-old.

There are ages and hometowns where you need to see deer, water moccasins, bears, and soft-shelled turtles. And there are ages and hometowns where you desperately need to see black and brown people, gay and straight people, blind people, deaf people, and people you can’t quite get a read on. And you need to understand that homeless people aren’t just camping.

Letting your feet walk in the shoes of others is probably the most critical step you can take after those you took from potato sack to wobbly wanderer. I am no longer just the boy born in Oklahoma, the mountaineer, the fearless southern carrot top, or the street-smart city kid. I am all of them. I am grown now, leaning more on the backside of my life than the front. And I live in the last hometown I will ever claim.

✤ ✤ ✤

Almost thirty-one years ago to the day, I followed behind a moving truck as it pulled into Rollingwood, my first apartment. Just a month and a half before that, I was playing the same DC-area bars I started in as a teenager, when the legendary songwriter, Tom Paxton, who had taken me under wing as a young writer, called the house.

“Mark, can you be in Nashville by the first of the year? I have a publishing deal for you.”

“Hell, yes I can,” I said. And then ran upstairs to tell mom and dad.

“What’s a publishing deal?” they asked.

“I have no clue,” I said!

That began my love affair with Music City. I made my living on music row. Back then, just three or maybe four streets contained our entire industry. I remember pacing drop-jawed up and down Sixteenth Avenue for the first time.

Everyone knew that street because of Tom Skyler’s song made famous by the singer Lacy J. Dalton, especially the hook line, “God bless the boys who make the noise on Sixteenth Avenue.”

Back then, big business happened in little houses. Those streets seemed to ooze powerful, famous, and talented people from very unassuming offices. It was a collegial neighborhood, where you could write a song in one house, walk a block or two to the studio in another house, and then walk a cassette tape another couple of blocks to a house that held a major record label.

In my freshman year in Music City, we all traded tennis shoes, business loafers, or sometimes, no shoes at all, for cowboy boots. And when those soles scraped against old-time sidewalks, they momentarily shared the long-ago imprint of a heel and toe from Elvis Presley and Hank Williams, Sr. And those of Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, and Waylon Jennings. And if you were a songwriter worthy of testing yourself in this town, you knew exactly what lay beneath your feet. You could feel the history of music flowing like a river beneath your pointy-toed Nocona’s. And you never wanted that feeling to end.

Nashville, Tennessee, has given me my highest highs and lowest lows, personally and professionally. Whether friendships, love affairs, hit songs or near misses, I’ve enjoyed the best and worst parts of all of them in this town.

I’ve delivered fuel to my friends on the side of I-40 in a small five-gallon can they bought me the month before when it was my turn to run dry. I have helped them move out of their apartments in the dead of night and then driven them to the big black gates of a country star’s home, and watch with mischievous hope, as they tossed a cassette tape with a lyric sheet rubber-banded to it, onto the perfectly manicured front lawn. We waited until the floodlights blazed on, hoping that the heavens would open and rent would fall out.

A friend fed me at Perkins Diner at 2am. He had a song on the charts, and I did not. That happened a lot! The first time, it was a cheeseburger and a sugar cookie, and we sat at a booth between the old boxer-turned actor, Randall “Tex” Cobb, and Charlie Pride.

This is my last hometown because all my past hometowns somehow lay within its borders. I am a prairie Midwesterner, a mountaineer, a barefoot southern Huck Finn, an eighties parachute-pant teen, and most of all, a word junkie. Like some kind of Appalachian song catcher, Nashville gathered all the memories I kicked up walking through this world, including when I propped my feet up in arguably the best music van ever and used those memories to convince me I am a writer.

I’m never leaving home again.

I just peeled my feet out of a black pair of Dingo’s, whose leather sides are perfectly soft, so much so that the brass rings are hanging loose over uneven heels. A lot like me. My first thought?

Wow, man, my feet are ugly, especially my toes! What’s going on with those toes?

I’m not sure “pretty” is the word any of us would use to describe a guy’s feet. But a full life plays hell on the prettiness of feet. And I suppose that’s why they look the way they do. You can’t hide the hard traveling of miles or long journey of years, and why would you want to?

Remember that souls pass through soles.

I’m singing a song in my head right now. It’s one I just wrote with my pal Davis Corley. The hook line sums up my life. And I think it may well be my best effort in describing my hometown.

“It’s hard to beat planting your feet where your heart is. Don’t you know it’s a lucky soul that winds up where it always wanted to go.”–Elliott/Corley.

✤ ✤ ✤

Mark Elliott is a Nashville-based singer/songwriter and author. He has written for some of Nashville’s top publishing houses, including Sony-Tree, Maypop, and Bluewater Music. He’s a winner of the coveted Kerrville New Folk Award and had songs covered by both indie and major-label artists. Mark’s book, The Sons of Starmount: Memoir of a Ten-year-old Boy, is out in paperback and audiobook, and his new single, “Talk To Yourself,” is out now on all platforms.

About the Creator

Mark Elliott Creative

Mark is a Nashville singer, songwriter & author. New single, “Talk To Yourself” & Memoir: The Sons of Starmount” — OUT NOW

Follow me on INSTAGRAM/TWITTER: @imacre8tivesoul

FACEBOOK: markelliottcreative

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.