ZANSKAR

“People live longer who cry,” Valerie said as she put her arm around me with a strong squeeze. This grey-haired stranger said the most perfect, comforting words. I sobbed in the dining room of a warmly dilapidated hotel, at 11,300 feet of altitude, in one of the most remote regions of the world.

I love to travel, backpack, have adventures. In June 2018 I left Albuquerque, New Mexico for a solo trek in the northern Indian Himalayas. Restless in my life, alone, son grown up, a job I enjoyed but was not deeply fulfilled by, I found consolation and joy in wild places, and the physical challenges of encountering them. Ladakh, the mystical land across the border from Tibet was the furthest place I could imagine. So I went.

I began to sort out the geography, trekking as planned from Manali to Leh across the Zanskar Mountains. A frozen desert. Melting glaciers topping the bare chapped flanks of incredibly high mountains. We were hiking from 7,000 feet of altitude, up to 17,000,. I had been at high altitude before, in Nepal and summiting 14-ers in Colorado a few months prior. On the 5th day of the trek I started hearing a stream in my ear . “Cool,” I told myself, thinking I was internalizing the landscape of thundering glacial streams. I wasn’t. The noise got louder, then filled both ears. I got weaker and weaker, until finally I couldn’t take two steps without stopping. I’m an endurance athlete, trail runner, long distance cyclist. I was mad at myself, not afraid.

Finally I lay down on the ground and told my guide to go ahead, I would catch up. Sherab looked at me with a mixture of concern and panic and told me to rest, he would be back. An hour later he did, dancing. “I got taxi!” he shouted. A taxi! I looked around at the narrow trail and rocky steep cliffs. There was no way a taxi could get here. Then I saw movement behind him. An old man was leading a slow pony up the trail. My taxi.

I held on to that pony for two days, whispering to my mount that I hoped he had a good sense of self preservation, otherwise we were both going off the cliff. Sherab was leading us to the small town of Padum where he knew there was a Government hospital. I thought I had pneumonia and would be fixed by a couple doses of antibiotics. The last part of our journey I had to dismount, walk over the “terrible bridge,” and climb about 100 vertical feet. It took me over an hour. I was pretty sick.

We got to town late afternoon. Sherab spoke to locals in the street, and said we would set camp, then come back to town at 6pm. That was a strange plan for a hospital, but I was in a foreign country, what did I know? At 6 Sherab led me to the entrance of a building, started walking up the stairs. “Are you sure this is a hospital?” I asked him, reading the sign that said hotel and dining. “No problem!” he reassured, like he did about everything.

When we got upstairs, walked into the dining room, there were the first Westerners I had seen on my trek. They looked tired, sitting in small groups and getting up for tea. I collapsed in a chair and waited, noticing the grey-haired woman was the hub. People checked in with her, consulted, glanced in her direction. She got up, walked over with a limp and cane and sat next to me. That was how I met Valerie Hellermann. The group she was with was the Hands On Global medical team, which she had started three years before.

I am not the first person to say this. Valerie saved my life and changed my life.

Valerie suggested I move into the team’s hotel. They arranged to borrow portable oxygen from the hospital, took a nebulizer from their own clinic, and hit me with more drugs than I had ever taken in my life. Since they weren’t exactly sure what was going on, I got it all for severe respiratory illness. For four days I had the best 24 hours a day healthcare in the world. Constantly being checked on by members of the team, and a nightly reiki treatment from a Brazilian volunteer, Thiago. He gave me a Tibetan healing stick of precious stones to hold. I learned it had been passed among the group of doctors, nurses, massage therapists and other volunteers. Each one put their prayers and intentions for healing into it. I felt behind all this care the presence of Valerie, her hug becoming the actions that saved my life.

Back in the States I reach out to Valerie. I wanted to know more about Hands On Global. I wanted that connection with an amazing woman to deepen, knowing that our journey had just started. Since she lived in Helena, Montana and I in the Southwest, we did our catching up over the phone. Her cheery musical voice filled in some of the details, punctuating auto-biography, world-view and cascades of sorrow and joy with laughter.

Valerie trained as a nurse, and always had a spirit of adventure and service. She travelled all over, but especially in Asia, stopping time and again to volunteer in orphanages and clinics, working with major NGO’s and small grassroots efforts. “That’s where I first saw the poverty and the inequalities of the world. I wanted to do something about it,” she said. While working at a refugee center on the Thai/Cambodian border with some of the bigger NGO’s, she was dismayed to see them governed by politics. Food sat rotting in warehouses, medical relief was inadequate because of bureaucratic log jams.

At home she volunteered with a local church group, doing the Midnight Run. It rotated among various groups, driving to New York City on Friday afternoons from upstate where she lived to distribute some limited medical care to the homeless. Just dressings, sanitation, wound care, cold remedies. Small things. Mostly, Valerie told me, “It was about bringing them into contact. Just being there, looking at someone face to face and saying, “I see you. I care about you.”” This is the mantra Valerie carries inside her. To be present to another person’s life and pain, not hide away.

Valerie got involved in more service organizations, had a child, moved to Montana. There she started volunteering with the Tibetan Children’s Educational Foundation (TCEF), eventually became Project Manager for 15 years. She started taking service groups to India, where people could meet the Tibetan children they were sponsoring. Over the years Valerie learned tremendous lessons about how to truly be helpful to impoverished people. They might get to the children bringing books and pencils, and see that what was really needed were healthcare assessments, access to clean water, solar showers. She learned to be flexible. With a small organization she could do that. She started going to Dharamshala to meet with heads of the Tibetan Departments of Education and Medicine. She got involved with Tibetan ex-political prisoners who had been tortured in Chinese prisons. She worked with a grandparents program for the elderly—“They have great stories! They have great needs. I just got involved in everything!”

I picture Valerie as she is speaking. Late 60’s, energy and warmth radiating from her voice to the core of her being. The cane, the limp. I know she is dressed with pizzaz, a unique hat cocked on her head, matching her long skirt. A shawl jauntily draped around her neck, over her shoulders. I know this might not be flattering to her, but this image pokes in my imagination: her strong body as the figurehead on the prow of a ship, plunging through dark turbulent waters as she protects the crew.

Valerie got into Buddhism very early in her life. When she was visiting Boulder, Colorado she attended a dharma talk by a Tibetan Rinpoche, teacher. It made sense to her, putting some unformed pieces of her own thoughts into words. She went back to New York and was living in her van, trying to figure out what was next. Through synchronicities of the right people, right place, she ended up living in a house where a Buddhist sangha met, and cooking when their Rinpoche came for a few weeks to teach. During that time she took refuge with the Buddha, an essential Buddhist practice that continues to this day.

Her voice deepens with excitement as she tells me about meeting the Dalai Lama for the first time. “It was magical that it happened on my birthday, September 7, in 1979. I found the invitation recently so I know it exactly.” His Holiness was speaking at St John the Divine in New York City, and Valerie took the bus to be there. “He was the same, laughing, a beam of light,” she said. “I felt like the universe was aligning for things to open. I saw the opening and stepped through.” She would get to know His Holiness in a much more personal way throughout the years.

In December of that year Valerie was in a major car accident. She was hospitalized for six months, still lives with the impairments and pain from those injuries. In a truly Valerie way of looking at things, she shared, “I was just so lucky that I had been involved with Buddhism because the Rinpoche would come to see me once a week. He talked to me about this accident being a purification, and he taught me meditation to deal with the pain. I still use that meditation.” A member of the Sangha came to visit and he echoed the Rinpoche, telling Valerie that she was so blessed to use the purification to delight in the teachings of the Buddha in this lifetime.

You are nuts, Valerie thought to herself, but sat with it, eventually deciding, “Well, I could do it that way. Makes a lot more sense than poor me.” She won’t let anything stop her. You cannot offer to help Valerie navigate a rocky path or lift a heavy piece of luggage or climb a ladder unless it is absolutely evident that anyone in that situation would need help. I’ve seen her put her cane aside and fly up and down three steps of stairs at a refugee clinic all day long, only stopping at the end of the day with a sigh and a grimace.

As she said, “I do believe all our challenges are ones we can learn by. I can allow myself to get stopped for a couple hours or a day, but not much longer. We learn how to use it and move forward. This outlook comes from Buddhism. We can use everything to figure out how to progress in life and help others.”

In 2013 she took a trip to India, still working with the TCEF. In Dehradun she met Geshe Yonten from Zanskar who was looking for ways to get Zanskari kids a better education. Valerie was accompanied on her trip by a friend who was also a nurse, and together they started doing basic medical exams and treatments for the the children they were visiting. Geshe Yonten invited them to come to Zanskar and see how poor the healthcare was there, see if they had suggestions to improve it. Sure, they said. A year later Valerie organized a small group to go to Zanskar. Two nurses, a photographer, an anthropologist, and one random young person all took the impossibly long trip to get there.

The group set up a little clinic attached to a teahouse in a village just to get an idea of the needs. At the same time the Dalai Lama was in the nearby town of Padum giving teachings. Geshe Yonten brought the group to visit. Valerie had already had many meetings with His Holiness due to her work with TCEF. In a private room, he told them that his foundation was setting up a hospital in Padum. It was important because Zanskar was the last authentic stronghold of Buddhist culture. He feared that if China continued their political agenda in Tibet, that would be it for the culture. He looked at Valerie and said, “You must continue this work.”

Valerie agreed, although she wasn’t exactly sure what the work was. A few weeks later, back in Leh, Geshe Yonten brought Valerie to a meeting of the Zanskar Health Committee. The hospital the Dalai Lama Foundation was building was to be a collaboration of Western allopathic medicine and traditional amchis. They told Valerie the Dalai Lama wanted her to open the hospital with a medical camp. “Okay, that’s the work’’,” Valerie acknowledged. Never did she doubt that this was her role.

In July 2016 Hands On Global came to open their clinic in Padum. Valerie said putting together team was part of the magic of the experience. She called medical professional friends and they said yes. People called her saying they had heard about it and wanted to come. “The right people showed up. They always do.”

AFTER

I went back to Zanskar in June 2019, this time with Hands On Global. This was the 4th year of the 5 year commitment Valerie made to working there. Her goal is to turn the clinic over to the local medical providers. I met up with Valerie on the flight to Leh, catching a glimpse of her through the windows of the bus taking us to the plane for the domestic flight. Long black embroidered skirt flowing to her ankles, black velvet jacket, a sporty straw hat tipped back as she talks to the young man next to her. “You look beautiful,” I tell her. “Oh, Zoe,” she says, “So glad you’re here!” We hug, and I am chastened in my t-shirt and tech pants, knowing there is little I can contribute to this amazing medical team. The southern Himalayas pass beneath us, a field of pure white crinkled with blue shadows.

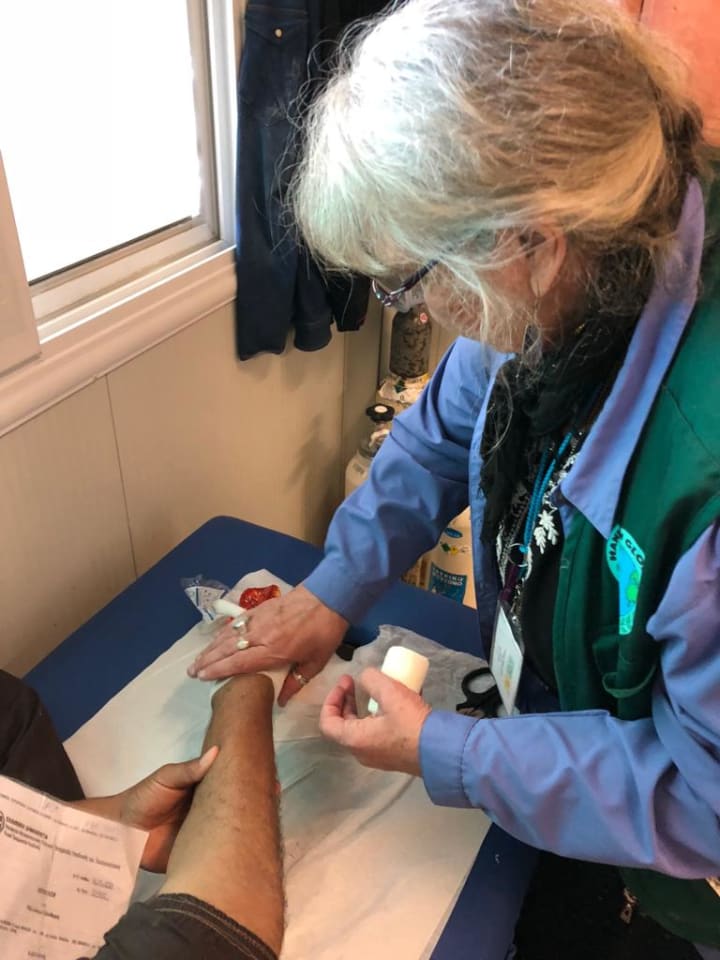

It was different this time. I spent time in the clinic, helping as I could by keeping track of patients, bringing them to the rooms for massage or physical therapy. People waited at the door as the clinic opened, most in traditional wool dress, layers and layers to keep out the cold. The providers might see 30 to 100 during a day, aided in their treatment rooms by the young interpreters, who, practicing their English, volunteered to translate. One little task I did at first was wash the feet of the massage clients. Washing is not a common practice in Zanskar, and their feet, especially the elders, had years of grime embedded in them. I never thought I would be washing another person’s feet, and it was surprisingly intimate and tender. I would look into their heavily lidded eyes, then touch and gently scrub their feet. Thank goodness this job was soon taken over by the interpreters, who zealously jumped in and attacked those feet until they were red as baby’s skin, the rinse water turned black.

When I went to Zanskar in 2018 I trekked on top of the land as a visitor. With Valerie and Hands On Global, I became part of the land, as they were. Valerie took the thread of her compassion and skill, became the weaver of all our lives into a beautiful tapestry. For all the volunteers, I know time with Hands On Global was a peak experience. As Mark Ibsen, a doctor who has gone for a few years with the team says, “Valerie saved my life.” He went on to say how, for personal reasons, that brought him peace and rejuvenation. He added, “Though sometimes she tried to kill me. I’d have seen a 100 patients that day, would be exhausted, ready to close the clinic and go, when Valerie would walk into the room. She would look at me and say, there’s five people who walked 30 miles to get here. Can you see them? And of course, I would.”

We were invited to the interpreter’s homes, went on hikes with them. Visited monasteries, attended a festival, had parties, drank beer and arrak, danced. Some learned how to make momos, a delicious traditional dish. Some held elders hands as they walked the stairs, shared laughter without words. On a truly memorable evening towards the end of our time in Zanskar, we were invited to Milton’s village for dinner. Milton wasn’t his real name, but the one Hands On Global people had given him to make pronunciation easier.

We drove to Milton’s town in the evening, a typical bumpy ride for almost an hour. The whole town knew we were coming and greeted us with joyful “Julley” a greeting that really welcomes the friend and the stranger. Before dinner Milton’s grandfather, a high lama came to speak to us. He told us that as human beings we were given the gift of a very advanced lifetime. Our duty was to be of service as best we could, to help ease other’s suffering. It resonated deeply with all of us. Then we were served a feast, huge pots of rice and curry and breads and vegetables. Arrak flowed from white buckets. Darkness outside, Shane stood up and sang, first a sorrowful traditional love song, and then one of his own compositions. A capella, wonderfully, a sharing that shone with his love for everyone around him.

BEFORE

I had joined the Hands On Global team before Zanskar. In October 2018 I went with them to the Moria Refugee Camp on Lesvos, Greece. As Valerie learned of the tremendous need for medical care at what has been called “the worst refugee camp in the world” she looked for volunteers again to go with her. By the time I went with them, Valerie had expanded the refugee work to the US/Mexico border, and had visited both Moria and a camp on the island of Samos.

Thousands of refugees crowded into the camp. It had space for 3,000, but at that time 8-9000 lived there, overflowing into the Olive Grove outside camp. Right now, there are 22,000 people at Moria. They come from 70 countries, Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, Cameroon, Congo and Somalia. The list goes on. Patients came in with unhealed wounds from bombs and war; sickness from unsanitary conditions; scabies and parasites. Sometimes cancer, high blood pressure, gynecological issues. They had scars from torture or fights. Many could not sleep at night because of the screaming around them, as people relived the horrors they had been through, in waking dreams.

The refugees, if they were lucky, had a tent to sleep in, or an isobox they might share with 10 others. If they were really lucky they had a blanket and a pallet to sleep on to raise them from the cold ground. They waited in long lines for hours for food. One man showed me a video he had taken on his phone of maggots crawling in the food. I saw a family clutching a few pieces of cardboard, a treasure to put on top of the pallets for a little more comfort. Children played as they always do, in among the overflowing barrels of trash and tents leaning against each other. There might be one shower for 600 people, the same for toliets. Water ran from a spigot outside for both hygiene and cooking. There was one doctor at the Greek government clinic, the rest of the needs were taken care of by volunteer NGO’s, who showed up, and left in a constant flow from the camp.

The first time Hands On Global came to Moria, they worked out of the back of a van parked in the Olive Grove. Patients were treated, medicines dispensed, massages done under tarps they set up for weather and privacy. When I joined them in 2018, the team had partnered with another medical NGO, and we shared the makeshift clinic right inside camp. Working there, Valerie said, “Is like putting a bandaid on a hemorrhage.”

I listened to the refugees’ stories, in English when they spoke it, with the help of our interpreters when they didn’t. Every one had experienced unimaginable suffering. A young woman, 18, fled Afghanistan after the Taliban killed her father. She got separated from her family and has no way to find them. A man who escaped slavery in Mauritania. He lifted his arms and showed me the white bands on his dark wrists, where the chains rubbed skin away. A teacher of chemistry from Syria. A financial analyst from Iraq. A single woman from Ethiopia whose family was killed. A young man from Ghana, beaten nearly to death in Turkey for carrying a bible. His father was a traditional priest, and for his son to reject those ways, if he stayed in his community he would be killed as cleansing for the gods. A woman from Senegal raped in Turkey and raped in camp. What everyone shared and few spoke of, was the treacherous trip over the Aegean Sea from Turkey to Greece. In Greece, at least, there was hope of asylum, so they mounted the flimsy rafts at night, launched to sea by smugglers who only gave enough fuel to get away from shore. Then they drifted, all night until washed up on an island. One man told me of his trip. “It was okay,” he said. “Some died.”

What do you do with the feelings that come up, witnessing Moria, hearing the stories? Valerie had warned of PTSD for the volunteers. My way of coping was to walk to camp in the morning, or go for a run. One day I as walked it started raining. A Greek man riding a bicycle stopped and offered me an orange. I peeled it, listening. I am probably not the first to notice that birds even sing in the rain.

On a day off—we took one a week—we visited a graveyard in Mytilene, the town near Moria where we stayed. At the very end of the cemetery, near the wall, were unmarked graves, for the bodies without names. We picked flowers, put one on each grave. The workers at the cemetery waved in acknowledgement and sympathy. The Greeks truly have been remarkable, but now with unceasing waves of refugees, and all of Europe shutting their doors, they cannot take anymore.

This team, everyday dealing with the most vulnerable people on earth, saddest stories, trauma, anger, fear as well as bodily injuries. One afternoon a young man was brought to clinic in wheel chair, his friends shouting as they pushed. Blood ran from his nose, he was pale white from shock. The team rushed him into a treatment room, and he stayed there for hours. Later I learned that he had been playing ball with his friends, was hit in the face. Nosebleed. The boy screamed and passed out. How to understand this? Valerie said quietly, “I can’t even imagine what this young man has seen, that this injury caused him such trauma.”

Later I asked Valerie what she would say to someone who tells her how selfless she is. She answers, “I don’t think of it as selfless. First, I love what I do. I do that for me. I recognize my privilege. I have a great life. I’m not rich, but I have everything I need and it grieves me about the inequality of the world. And it hits me more and more that I want to share what I have with others. I don’t have to solve the situation, but I do have skills and I’m a good organizer. I love doing that. That’s what I have to give.” And so much more. I hear Valerie tell a story about greeting an African man in camp. He told her she smelled like roses, like his mother did. She was slaughtered in front of him. “Can I give you another mother’s hug?” Valerie asked him. They held each other and both of them cried.

Valerie would be the first one to say she’s not a saint. She laughed when I mentioned Thiago called her “A living Bodhisatva.” A Bodhisatva is a holy being who takes a vow not to merge with God until suffering has vanished from all sentient beings. None of that for Valerie. “Its about action,” she says. “Buddhism teaches compassion with action. I’ve always been that person standing on a street corner holding a sign. I’m a doer, and I have a certain amount of willingness to go into another culture and be uncomfortable, not have all the amenities. Be kind of puzzled how you should act. It takes a kind of bravery, and the people who come to me have that.” She tells a story of when she was working with the Tibetan political prisoners, a photographer took photos of their torture scars. She brought the photos with her when she went to fundraise, saw many people looking down. They didn’t want to see. There is a room with the photos in India, and Valerie always makes herself go see them.

“I force myself to go and I always leave in tears. But when you see it, you know you have to fight it. Going back to Moria was really hard, because I saw what can only be described as the truth that the world is descending into chaos. We can not live on the planet this way anymore. I could see the chaos but I don’t see solutions. But what I want these people to know is that I see them, I care about them, and I want to tell their stories.”

I listened to some talks on compassion, wanting to understand it better. Krista Tippett, in her TED talk, sees a problem with word being “hollowed out…seen as a a squishy kumbaya thing or depressing.” Valerie is neither squishy nor depressing. She is actually a riot, funny with a laugh that rocks the room. Earthy in her joys, good food, wine, loves getting her hands dirty in her garden. A few of us went to Istanbul after Moria. Valerie took advantage of the Turkish baths. On return, Valerie raved about it. “That chest massage!” She is mischievous and definitely can bend a rule. One of the team doctors, told me that on a trip to India, a friend of Valerie’s asked her to bring over a wheelchair he bought for his daughter. If it was shipped he would have to pay exorbitant taxes. Valerie came up with the plan to ride in the wheelchair through the airports. At one point the wheelchair was misplaced by the airline, and they offered her another. “No,” Valerie said loudly, “I want MY chair!” They found it for her.

Tippett goes on to say that compassion is linked to kindness, curiosity, beauty, tenderness and the simple act of presence. “Compassion is visible. When we see it, we recognize it, and it changes the way we think about what is doable.” As Valerie knows, compassion in itself is rarely the solution, but, Tippett says, “It is always a sign of deeper human possibilities.”

In the threads that connect us, something quite unexpected showed up for me. After I got back from India I had a message that I hadn’t been able to get earlier. It came from a man from Cameroon I met when I was at Moria. We talked a few times, and he always bared his soul. “I cry for myself, and for my pity for others here,” he said. Just before he left he asked for advice. He was sure he was causing his wife’s miscarriages, wanted to know where he could get treatment. He and his wife have an incredible love story, one of horrendous suffering, and yet they survived. Both had been beaten, sexually abused by a monstrous officer high up in the military, left for dead. His brother had been killed trying to intervene. Now they were in the hell of Moria. I reassured him that it was just circumstances and stress, and that at some point things would get better.

After I was home, he contacted me twice, once to ask for help with a warm jacket for his wife, another time for shoes. It was desperately hard for him to ask. He was the man, he told me. His job was to take care of his wife. A nurse with Hands On Global had stayed at Moria, and through her we were able to get them warm clothing and shoes. Such a small thing. Accompanying the message he sent were photos of their daughter, born in Athens instead of Moria. Though they had wandered the streets for days with shelter or food, eventually a kind person helped them. They named their daughter “Zoe,” after me! She is beautiful, and I get updates of her learning now to walk, glancing at the camera with dark knowing eyes.

Valerie is part of this family as well. She offered that if I could raise $500, Hands On Global would match that. When she and the team went to Samos again, she met with my friend in Athens and gave him the money so that he could live with his family, have safe shelter and food for a while.

Valerie often says, we can’t help everyone, but we can help the one in front of us. Hand to hand, heart to heart. She ends every email with this quote from the Talmud:

Do not be daunted by the enormity of the

world’s grief.

Do justly, now.

Love mercy, now.

Walk humbly, now.

You are not obliged to complete the work,

but neither are you free to abandon it.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.