Coddiwompling around Whitechapel

Wolf Mankowitz, George Bernard Shaw, Judi Dench and the chance to learn Arabic

After a tube journey from Waterloo to Whitechapel in dreary yellowy half-light we came to the surface like moles breaking out from their underground tunnelling. Wide eyed and blinking, our eyes adjusted to the bright spring sunshine and kaleidoscope of colours around us. We had surfaced into the middle of one of London’s richest multicultural environs. It felt like changing from monochrome TV to colour.

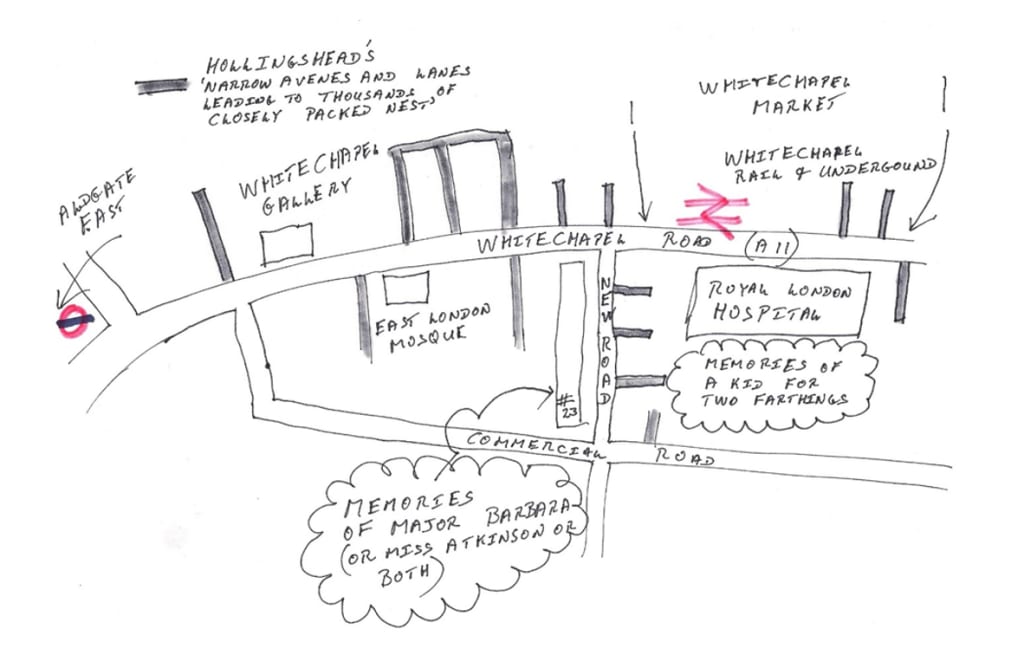

There wasn’t much time to take everything in as we had to find the venue where my wife was working for the day. It was somewhere between Whitechapel and Commercial Road. We had worked out a route. It was going to take us through car parks and narrow lanes that surrounded The Royal London Hospital and past the hospital’s museums. As I am squeamish at the best of times about flesh, blood and visceral things none of these would be on my list of places to visit today. We walked through sanitised and tidy streets lined with Victorian rows of houses that had been or were in the process of being updated to the 21st century.

I said ‘sanitised and tidy’ with good reason.

In 1861 John Hollingshead wrote a book called ‘Ragged London’. This was a collection of his reports of his walks through London during the famine of the late 1850’s that were published in The Post. He recorded that while taking a walk from Aldgate to Old Whitechapel Church ‘you may well pass about twenty narrow avenues leading to thousands of closely packed nests. Most likely some of the very streets we were rushing along towards Commercial Road.

Hollingshead describes the streets ‘as full of hunger, dirt and social degradation’. Each shabby front he passed in his walks was a thin façade hiding rooms no bigger than ten feet by ten in which families of up to seven lived, if ‘lived’ were the most suitable word available. Inside the rooms people were covered in dirt and grime including babies whose paleness still pierced the darkness of the dirt. If the house had any windows and providing they were not broken and stuffed with rags they would look out on to puddles of rainwater, sewerage, dust heaps and piles of rotten vegetable refuse. The children had little or nothing to do and Hollingshead described them as ‘human child rats’.

‘Dickensian’ to my mind is the most appropriate adjective or even collective noun for his work reputed to be one of the earliest examples of investigative reporting.

These were also the streets and alleys where Jack The Ripper stalked his five victims during those dark ill lit nights of eery shadows, billowing mists and silences only broken by the sound of footsteps fleeing the scene of the crime. Today there were no eery shadows, billowing mists or silences.

The streets we walked, or as Virginia Woolf would have called it ‘haunting’, even though it was in broad daylight, were deserted and felt much like the streets of Trehafod when I met the ex-miner with a nasty cough and an enthusiastic collie.

Along one of the streets was a building whose end wall bore a faded name and their profession, a tailor. Memories of my English Literature classes some fifty years ago resurfaced. They were not so faded or so I would like to think.

A compulsory book on the course was ‘A Kid For Two Farthings’ by Wolf Mankowitz. It was about a young boy, Joe, living with his single mum in Whitechapel. In the basement was a Jewish tailor, Kandinsky, whom the boy befriended. The old tailor used to tell the boy stories about unicorns and how if you were lucky enough to touch the horn of one your wishes would come true. Joe managed to save two farthings which he spent buying a kid goat. He believed it was a unicorn because it had a slight bump in the middle of its forehead. It was going to grow into a single horn. Joe used to touch the horn wishing for a better life. The wish never came true, the kid became ill and eventually died but Joe never gave up wishing.

It must have been well written as nearly sixty years later I can still remember the story and our English teacher reading it to us while we counted down the minutes on the classroom clock to games outside under a summer sun.

We found the venue where my wife was to work for the day. We parted company and I set off on my solo meanderings around Whitechapel.

At the end of Nelson Street is New Road. Facing me was a row of four or five story buildings left over from the Victorian era. Most of the row looked tired with chipped and flaking paint and plaster. They were ready for a makeover. Number twenty-three New Road had a sign advertising Professor Orson’s Dance Academy and a blue plaque. As far as my limited knowledge of dancing was concerned I wasn’t aware of any famous dancers that had graduated from the academy or if the plaque was dedicated to the Professor himself. When I got closer I could see it wasn’t to do with dance. What it stated was that on 3rd September 1865 was that the first indoor meeting of the Christian Mission took place. In 1878 the Christian Mission changed its name to what is now a world- wide movement, the Salvation Army.

That is the beauty of London. It is so full of history that it is inevitable that somewhere along its streets and lanes there will be something for everyone that will evoke memories from somewhere about something.

Twenty-three New Road did to me what passing that small tailor’s shop a few minutes previously had done. It brought back memories of later days at a college and more English Literature classes. One of the set books in those classes was ‘Major Barbara”’by George Bernard Shaw. The backstory was that Barbara came from a wealthy family, the Undershafts, whose money came from weapons, and it was while she was in the Salvation Army doing good for the poor she met the love of her life. This caused a conflict about life with her father, her family, and the morality of money whatever its source. In the final scenes in a Disneyfied frenzy of forgiveness and reconciliation the play ended happily with everyone understanding everyone else.

Our lecturer was a Miss Atkinson who could not have been much older than us. As well as being a fun person taking us for English lit I and the other males in our class were convinced she was a size fourteen who always optimistically wore a twelve. Believe me we did concentrate in her classes but not necessarily on the course books.

Two literary memories and some teenage voyeurism in less than a mile was not a bad start to the day or however long I had to explore.

I drifted back to Whitechapel Road past more housing, takeaway shops, taxi offices and convenience stores that exuded aromas from different parts of the world. Past the East London Mosque where men, women and children flowed in and out of their respective doors. Directly opposite the mosque was a travel agent whose windows had posters for special fares to various parts of the Middle East and the wider Islamic world. Bargains to Lahore, Algiers, Turkey, Beirut and even Damascus in Syria where news from the civil war was headlining our media outlets.

By now it had been a long time since breakfast back in Ringwood. Although I was being geographically adventurous in London my stomach was telling me not to be quite so adventurous. So, having walked past Lebanese, Indian, Turkish, Bangladeshi, and other Orientalist eateries I am ashamed to admit that I settled for a standard western venue holding out to be French.

The Whitechapel Gallery was open as it is every day. This day there was an exhibition of street photography both stills and video set out in different rooms. There were rooms with permanent exhibitions as well. All of it was challenging and raw and the gallery was crowded with all generations.

As I approached Whitechapel Station the more crowded the street became with market stalls selling everything from fruit and vegetables and bolts of brightly coloured material. The pavements were thronged with people. Things looked bright, vibrant, and different. Men, women, and children passing in all directions and speaking different languages. I really did feel a stranger in town. An outsider through the endowments bequeathed to me through the accidents of birth and family.

My mobile phone vibrated taking me away from my own very personal here and now of experience. The text that came through was from my wife to say she had finished her work and was ready if I could meet her back in Nelson Street. I retraced my steps. Past the gallery, the mosque where there was still a never ending flow of people, convenience stores, take aways and housing. Past twenty- three New Road and on to Nelson Street where I met my wife.

We walked back towards Whitechapel Station. This time we stopped at a charity shop across the road from the mosque where we bought a second-hand prayer mat. There were others available with compasses sewn into them pointing the devout towards Mecca from wherever they were in the world, including Whitechapel.

Eight years since buying this prayer mat and having used it as a mat for our cat and as a cover for an Ottoman our household has not been visited by the Islamic equivalent of a bolt of lightning.

Then we stopped at a small stall selling children’s clothes. Our neighbour’s daughter was about to celebrate her first birthday, so we stopped and had a look. All the girls’ clothes looked almost western but there was something different about them. The style, the colours, the quality; we couldn’t work it out. We saw a white dress patterned with bright red roses and thought that would be perfect for the little girl. While I was sorting out the money my wife went on ahead to look at some other stalls. The stall holder had treated us as his average type of customer. He gave me the dress in a bag and my change. I said ‘Shukran’.

His whole demeanour changed.

‘Where did you learn Arabic?’ he asked.

‘I am doing an online course.’

‘No good my friend. You come London. Work for me three weeks. You learn Arabic proper. Online course no good. Learn here in street like I learn English, on the street.’

He then went on and explained that he had left Bangladesh several years ago to work in the Middle East. Then he worked on some ships travelling the world before deciding to settle in Britain which he said was the best of all the countries he had been to. We shook hands.

‘You come work for me next week. Promise you speak proper Arabic three weeks. No online course.’

‘I don’t think my wife would be too happy.’

‘OK, ma a salaam my friend, ma a salaam.’

The girl and her parents loved the dress. She soon outgrew before her second birthday but it hasn’t been handed into any charity shop. It has been carefully wrapped in tissue paper, put in the memory suitcase being put together for her in the hope she too will have a daughter one day who can wear it on her first birthday.

Mar 16

About the Creator

Alan Russell

When you read my words they may not be perfect but I hope they:

1. Engage you

2. Entertain you

3. At least make you smile (Omar's Diaries) or

4. Think about this crazy world we live in and

5. Never accept anything at face value

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.