Then I realized I was the problem

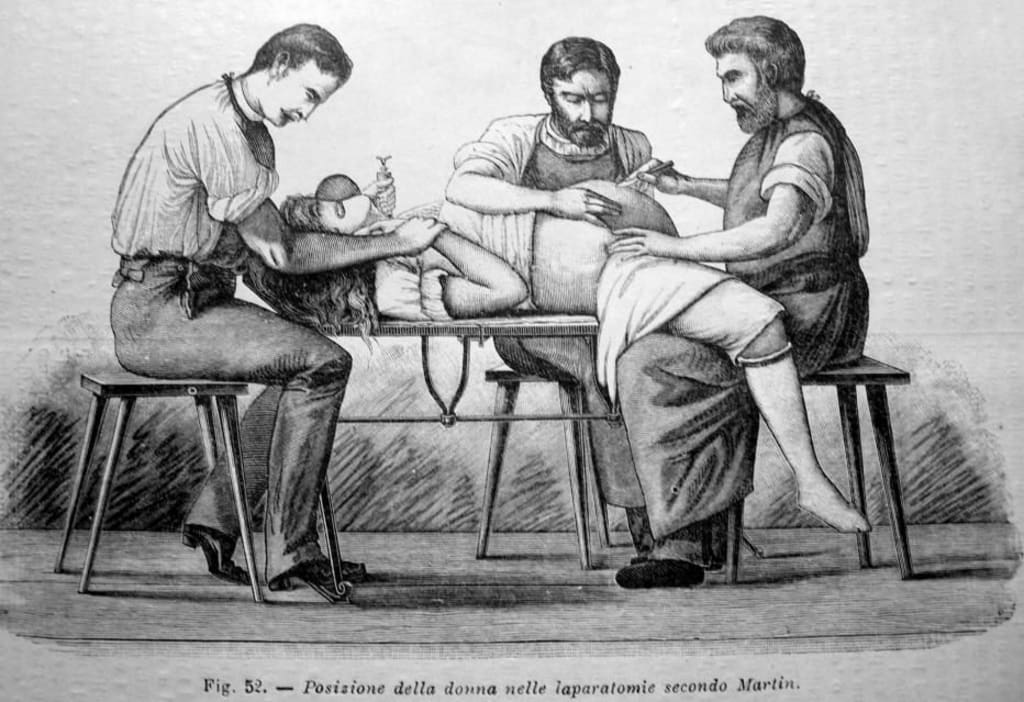

Reflections about racial inequality in women's healthcare and the deep seeded biases that effect how we practice.

I am ravenous for the voices of midwives and women. Every long drive to placement, everyday spent cleaning with my headphones in I consume every bit of perinatal content I can get my hands on. Anything even vaguely related to childbearing, from the memoirs of midwives to motherhood podcast and books on feminism or Montessori. I slurp it up, rewinding each time my vacuuming distracts me and I miss an important piece of information. I want to get inside the minds of the women I serve, feel what they feel so I can give them the care they actually need. There are deep rooted problems in maternity care. As my education and experience blossoms I find almost every piece of information I receive contradicting some other piece of information, meaning I am constantly trying to shove it into the jigsaw in some way it makes sense. Sometimes I've had to disregard some pieces, assessing the what is the most up-to-date evidence based piece. Generally it’s the things most people don’t talk about enough that are true. The things that turn sour in my gut when I see it in practice. When I heard the statistic about African-American women in the USA dying of pregnancy related complications at 5 times the rate of their white candidates (Center of Disease Control and Prevention, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0905-racial-ethnic-disparities-pregnancy-deaths.html), I could scarcely believe it. When my teachers told me about racial discrimination in our own hospital system, I forced it to make some sense in my mind; perhaps they’re just talking about some highly remote country hospital, where they ‘accidentally’ use the wrong terminology, or serve them a culturally unsafe meal? Then I went on my first placement.

I was on the morning shift on the postnatal ward. Myself, a shy second-year, shadowing a silver-haired battle-worn midwife who appeared completely too flustered for my young, highly efficient self. I respected her highly, none-the-less, assuming her inefficiency was caused by the intense mental juggling act she was doing around meds, discharge timing, trial of voids and wound dressings. Toward lunchtime we checked in our patient in bed 4. The woman in bed 4 appeared African in appearance and accent, and she’d been chattered about at the nurses station and by whispering neighbors for eating pungent curried fish brought in by her husband. She sat cross-legged on the bed, wearing nothing but a colorful yellow skirt and headwrap, her baby boy, suckling contently at her dark-skinned breast.

“Knock knock, How are you going in there?” I announce myself, pretending the curtain is a door and pulling it aside, forgetting that the purpose of the door is to protect privacy until invited.

“Yeah alright-“ The women shifted, squinting and sucking through her teeth in pain. “I’m actually very sore.” She gestured to the dressing across her lower abdomen.

“Okay, what’s the pain like out of 10?”

“About a 6.” She inhaled sharply again, still cradling her babe. With consent, I examined the wound. No redness, heat or swelling to indicate infection. Some fresh blood stained the honeycomb sponge, but I’d seen older midwives shrug at things like that, say it’s normal. I called in my buddy.

“What’s the matter?” She hurried from someone else’s room. I explained the situation to her, and she surveyed the women. “Have you tried uncrossing your legs?” She asked “I bet it’s just because of how you’re sitting.”

“This is more comfortable for me. I think I just need some pain relief.”

“Okay…” The midwife swept out of the room and I followed.

“So what PRN’s (Medications listed to be given as needed) does she have?” I asked, grabbing her folder.

“She’s already had Panadol today. If she was really in pain, she would uncross her legs. We’re going on lunch.” I blinked at her response.

“O-kay.” I say following her. How could we leave this woman in such pain? For the sake of pushing lunch back 5 minutes surely we could get her some Endone. I’d seen how quickly this midwife responded when the other women have complained, even of milder, niggly pain; bringing whichever opioid seemed sufficient. Surely this experienced, omniscient midwife was doing some advanced mental math, putting together clues I hadn’t seen to deem this woman unsuitable for pain relief. Maybe she should just uncross her legs, and all the pain would go away. We ate our lunch, chatting about her grand daughter’s graduation, and my new puppy.

Satiated and eager to get my OBS (Vital signs) round done before the next shift came on, I returned to the ward, leaving her to follow 5 minutes later.

The light above bed 4’s door flashed silently, and I went to it immediately. Hearing the woman’s cries I didn’t hesitate in throwing the curtains open. The women’s legs were uncrossed, splayed awkwardly across the bed, she breathed heavily and moaned.

“It hurts so much, why did nobody come?” The baby cried in the plastic cot beside her. She clutched at her belly, as if letting go would let it fall apart.

“Out of 10 how-“

“11! This is the worst pain I’ve ever felt” The sweat from her forehead mingled with tears on her cheeks. I rush out of the curtains, spotting a OB/GYN and pushing my body in front of him.

“Please come assess this woman, she’s complaining of severe pain.” The doctor eyed me, as if trying to assess my request worthy. The woman’s loud moan turned his head and he floated in, trailed by two excited looking interns. The midwife followed ran over, only just returning from lunch.

“What’s going on?” She demanded.

“Her pain’s gotten worse.”

“Ahhh.” She huffed, rolling her eyes as if this woman was some great burden. I watched for the minute as the doctor looked over the wound, whispering of uterine rupture, infection. The midwife whispered in the doctors ear while the woman tossed and turned.

“Please help me.” She begged. The midwife whispered something about crossed legs to the doctor and just before she waved us out of the room I hear the doctor ask;

“Do you think this might be because you were sitting cross-legged earlier?”

I’d love to say that was the last time a woman begged me to help her. I’d like to say I listened the next time. I’d like to say I demanded the best for her, advocated for her, but unfortunately it took another incident before I realized the depth of my bias.

It was 0500 hours on the last shift of my third year placement period. The night had gone quickly, I’d already delivered one baby, and just as we were getting ready to send the family over to postnatal, I was rushed into another room.

“This woman just arrived, hopefully you can get another catch (Catch of a baby. I need 40 to receive my qualification, so they’re a precious commodity amongst midwifery students).”

“Great!” I said.

“Her files are still coming up but I think she’s a G3 P2 (This is her third pregnancy, she’s given birth to 2 live babies). A bit of a social history I think (Complicating social situation; often meaning substance abuse, child protection involvement or domestic violence)” She gave me a brief handover. “You’re working with Kyle (Obviously not their real name).” Kyle nods at me, waving me to follow him into the room. He is an older midwife, I hadn’t seen him around much, and he didn’t seem too happy to be lumped with me. We walk into the room to see a women, naked and writhing on the bed.

“Help me!” She screamed, her eyes bulging. As the waves of contraction came over her, she arched and her many black braids slapped her back as she threw her head back shouting. I couldn’t help but admire the power of her. Her wildness. Sweat weaved in weary-moving droplets down her flawless dark skin. She reminded me of a jaguar the way she roared and swayed as the contraction released her. I leapt to the cupboard, setting up the gas-and-air and turning it up to MAX (Inhaled nitrogen oxide, combined with oxygen, commonly used as pain relief in labour). With a nod of approval from my buddy, I offer her the mouth piece.

“She looks transitional (The stage right before full dilation, during which the women transitions into the pushing stage of labour. This is when many women start shouting at their husbands and saying they can’t do it anymore.)” I whisper to him, he nods in agreement.

“Alright, are you happy for me to check your dilation? It seems like baby isn’t far away.” He asks, and she consents. During the exam, the woman cries out, as another contraction sends waves across her rock-hard belly.

“Get out!” She roars, sucking hungrily at the gas and air. He backs away.

“6 centimeters” He says.

“Really?!” I say incredulously.

“Yep. Be careful, she’s getting quite agitated.” I rub the woman’s back, reminding her focus on the act of breathing in the gas.

“EPIDURAL!” She screams. And Kyle rings the anesthetist who responds quickly. As another contraction explodes inside her she cries out “Fuck this shit doesn’t fucking work!” she hurls the mouthpiece at me, missing narrowly and I pick it up, just in time for her to reach outstretched for it again.

The anesthetist rushes in pushing a trolley, studying the scene in front of him. The woman gasped in relief.

“Are you sure she’s not about to have a baby?” He asked Kyle.

“6 centimeters, I just checked.”

“Would you mind checking again?” Kyle agreed and with consent, performed another check, confidently announcing:

“6 centimeters”

“Alright, let’s get this epidural in.” He responds, setting up the sterile field.

“Thank god!” The woman shouts, writhing as yet another contraction seizes her. In the minute of relative calm between contraction the women’s breathes are ragged with panic and pain. I help her maneuver her body to sit of the edge of the bed, his her back arched like a cat. As the pains return at full pelt, she jiggles and bends and screams.

“Now, to get the needle in I’m going to need you to be absolutely still. If you move, I could injure your spinal cord. Are you sure you’ll be able to stay still?” The anesthetist asks, watching the woman apprehensively.

“Yes, I promise, please!” The woman begged.

“Keep her still.” The doctor instructs, his eyes drilling mine. I had my mission. I knew my role. The doctor added local (Numbing agent that effects the small region it is injected into), then inserted the long thick needle, after some careful palpation.

“Now, stay very still.” He tells the woman. It’s no good though. Another contraction. She moans into the mouthpiece clenched hard in her teeth. I hold her shoulders.

“You need to stay very still okay, concentrate on your breathes. I know it’s hard.”

“You don’t understand.” Her legs kick and the doctor struggles to keep the needle still. “I’M IN HELL!” I didn’t understand. It’s true. I can’t begin to comprehend the pain she was in. None the less I reassured her.

“It’ll all be over soon. Sooner we get this needle in the sooner you get the epidural.” She grunted in response. A familiar grunt. The grunt we’d been told about at school. Kyle looked at me. She was pushing.

“Are you pushing?” Kyle asked. “Don’t push, okay, you’re not ready yet.”

The contraction calmed and the anesthetist asked again if she could stay still. She promised she would. She promised she would try her best not to push, as Kyle warned her of the danger of pushing when not fully dilated. As the next contraction came, the familiar grunt came and she tensed and struggled against it. Kyle rolled his eyes at me. The anesthetist threw me a stern look.

“I’m pushing” She cried.

“Try not to push. Look at me, you need to stay very still, just for a moment longer.” I held her hand and she squeezed crushingly tight.

“I can’t help it.” She groaned. Her eyes were wide as she let out another strained growl. “There’s a head! The baby’s coming! I’m sitting on the head.” The midwife and anesthetist gave me nothing, they focused on the job at hand. They didn’t believe her. My stomach twisted, I felt so connected to this woman, I wanted to scream. Couldn’t they see she was about to give birth? I could feel it. Like my ancestors’ womanly wisdom screamed inside me. But they probably knew best right? The men were in command, and they’d given me my orders. Who was I, a lowly student, to question them? I turned my eyes back to the mother.

“Okay. That’s okay. It doesn’t matter, the important thing is to stay still. We’ll deal with that in a second. It’s going to be okay.” Somehow, in my few short years of practice I’d learnt to conceal the panic in my voice with smooth, easy to swallow honey, the words were calm and clear and the woman softened slightly beneath my hands. Just as the anesthetist triumphantly announced,

“Alright, the needle’s out. Try stay still a bit longer though.” Another contraction shook the room, the mother screamed,

“He’s coming!” And pushed. And I pushed. My instincts took control of my body and I pushed her shoulder slightly to the side, allowing the angle of her hips the reveal.

“The head’s there.” I say, in a disembodied, gently urgent voice. The anesthetist jumps back, as I lay the woman down. In the next breathe, her baby’s body slithers out, still in his membrane bubble. I pass him to her, and throw the midwife a towel. My heart is thundering in my chest and I do… something. Just do something to help. I snap a vial of syntocinon (Synthetic oxytocin, used to help the uterus contract to decrease the risk of bleeding during the delivery of the placenta) and draw it into a syringe.

Why didn’t I listen? Why did the woman screaming in my face, telling me exactly what was happening in her body, seem less credible than the men pretending they couldn’t hear her? Why had I, after careful aching reflection on the first incident, committed the exact same offense to the next woman of color I cared for? Why hadn’t I figured out that my co-workers can sometimes be deaf to the voices of women, especially black women? It was my job to make them hear, so why didn’t I? Because I am the problem. After all my reading, all my promises to never be that midwife, here I was, fighting desperately with my deep-rooted bias. The equations I do in my brain are tinged with a dark inaccuracy; White knows better than black. I know it’s not true, I know the severe importance of trusting these women’s voices. In the whole world, these women were the leading experts on their body. Yet I took the information, based on a professional’s brief, bias tainted judgement as gospel, ignoring the evidence in front of my very eyes. The scary part is, it could happen again. I do my reflections, I practice standing up to my superiors in the mirror, I tell myself to trust my gut, but what if it takes years to unravel the bias. So much of midwifery is based on split second decisions and emergency assessments, who’s to say in the rush I won’t default to my misplaced trust in ‘the experts.’ Whose to say in the heat of the moment I won’t shrivel up and stay silent? It’s hard to imagine yourself being so weak, so unjust and cruel. If I was reading this I’d paint myself as a villain in my minds eye. But I think we all have these dark roots inside of us, seeded by years of subtle racist conditioning in our society. What we need to do now, is dig, painfully. And start to pull it out.

About the Creator

Ellen Brady

I am a 23-year-old Nursing and Midwifery student. I like to write reflections of my experiences in the healthcare industry. Disclaimer: All names have been changed, stories told are a combination of many experiences.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.