Nellie Bly a Woman Who Inspired Others to Never Settled for Second Best

Female pioneer who fought for women's rights whilst changing the landscape of mental health treatment.

Nellie Bly is my hero, and I don't say that often because usually, my heroes let me down. Nellie Bly was born Elizabeth Cochran on 5th May 1864 in the suburbs of Pittsburgh. Her father was a labourer who went on to buy his own mill and make a considerable amount of money.

Elizabeth was six when her father passed away. He died without a will, which put the family into severe financial hardship. Her mother went on to marry again, but it was an abusive relationship. When her mother divorced her stepfather, Elizabeth took the stand at fourteen and told of the life they had lived.

Financially things did not get any better for the family. Elizabeth enrolled in college to become a teacher, a good job for a woman. But, after just one term, she quit returning to her mother to help financially. This was when she first realised how easy it was for her brothers to get a job and how hard it was for her.

In 1885, this feeling of inequality was enraged when she read an article in a local paper stating that all women were good for was marrying and keeping house. She penned a response to the article stating that women were good for many things.

Mad Marriages

The editor, George Madden, was so impressed with the response he wanted to meet the woman who wrote it. So he put an advertisement asking 'Lonely Orphan Girl' to contact him. When Elizabeth responded, he offered her a job. Her first piece for the paper was called 'The Girl Puzzle,' it stated that women were not only suitable for babies but many other things. She called for them to be offered better jobs. All women needed to succeed was equal opportunities. Again she used the pen name 'Lonely Orphan Girl.'

Her second piece for the newspaper was titled, 'Mad Marriages.' It dealt with the issues of the effects of divorce on women. It was a subject close to her heart, having seen the discrimination her mother faced. This time rather than publishing it under 'Lonely Orphan Girl,' she used the pen name Nellie Bly. The name had been taken from a popular Stephen Foster song.

The response to the pieces was overwhelming; Madden offered her a full-time job working for the Pittsburgh Dispatch. Many of the articles that followed concentrated on women's rights. They looked at women's roles in industries such as factories and the treatment they received.

The local factory owners were incensed with this reporting and complained to the paper. Not wanting to lose their sponsorship, Nellie was removed to the fashion and society pages, which were much more appropriate for a woman.

Six Months in Mexico

Nellie hated her new assignment and instead volunteered for the job as a foreign reporter. She spent several months travelling to and from Mexico, reporting on the new dictatorship.

Six months after starting this job, she wrote a piece criticising the government for locking up journalists that criticised them. The Mexican authorities threatened to have her arrested, so she fled the country. After that, she was back to the fashion and society pages.

Severely disgruntled with her assignments, she left the paper in 1887 and went to New York. Once in New York, she walked the streets trying to get a paper to hire her. After four months, she was broke and still had no job.

One day she talked her way into the offices of the New York World, run by George Politzer. She was offered an assignment where she would infiltrate a mental asylum and report back to the paper.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

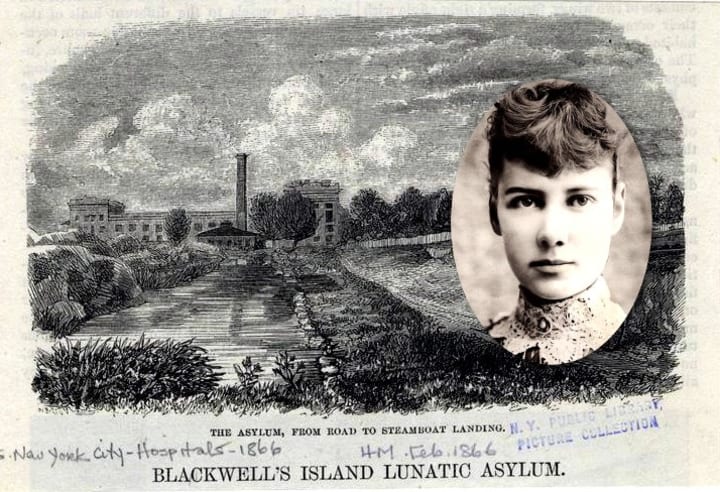

She agreed to fake insanity to be admitted. She first booked herself into a boarding house and started to act insane. She would never go to sleep and walk the corridors scaring others; she even went as far as practising mad faces in the mirror. It wasn't long before the police and doctors were called. She was transferred to the female asylum on Blackwell Island.

The conditions she found were worse than even she could have imagined. Patients were given rotten food and dirty water. The conditions were filthy and infested. During the day, patients were made to sit on benches for up to twelve hours, unable to talk or move. On arriving at the asylum, Nellie reported she was given a cold bath and then dressed wet. She spent the night shivering from her damp clothes.

In traditional Nellie style, she befriended the women and discovered their stories. Some were immigrants caught up in the legal system and placed there because there was nowhere else for them. Some were poverty stricken who again went there because where else was there. Nellie surmised that even if the women were sane on entering the asylum, within two months, the conditions would have broken their minds.

Nellie lasted ten days in the asylum before the New York World requested her release. She stated that the more she acted sane, the crazier they thought she was.

She published her paper 'Ten Days in a Mad-House.' The article caused uproar and prompted many changes to the funding and legislation of asylums. Nellie worked on the committees to help bring the change about. The article significantly changed the culture of marginalised women in America and propelled Nellie into celebrity status.

Around the World in Eighty Days

Nellie's celebrity status came with some perks. She could now talk herself into an interview with serial killer Lizzie Halliday. She started an era in journalism called stunt journalism.

In 1888, Nellie had another idea for an article; she wanted to recreate the journey carried out in Jules Verne, Around the World in Eighty Days. So on 14th November 1889, she boarded the ship Augusta Victoria to start her voyage. She had a small bag with a coat, scarf, change of undergarments, and a purse around her neck containing her money.

During her adventure, she travelled through England, Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan and France where she met Jules Verne. She also visited a leper colony in China. She sent short telegrams to the paper to keep them updated; they ran a competition to predict the date she returned to keep interest high. She travelled using steamships and existing railroads.

On 21st January, Nellie arrived in San Francisco aboard the RMS Oceanic, the sister ship of the Titanic. From here, she boarded a private train back to New York. She arrived on 25th January 1890, seventy-two days after she began the journey alone.

Marrying a Millionaire

After this, Nellie quit journalism and concentrated on novel writing, penning many books. She also met Robert Seaman, a millionaire manufacturer. In 1895, the couple married. Nellie was thirty-one and Robert seventy-three. Due to his poor health, she quickly took over as the head of Clad Manufacturing. Robert's company made steel containers. In 1904, Robert passed away, leaving Nellie in charge.

The company started to manufacture steel drums used in the modern oil industry. Reports state that Nellie invented the drum; however, the patent is held under another name. She did go on to have two patents in the name of Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman. The first was for a novel milk can and the second for stacking bins.

Nellie was considered one of the leading industrialists of her time. However, she had neglected the finances of the company. When her manager embezzled the company profits, Nellie had to claim bankruptcy.

Suffragists Are Men's Superiors

Nellie went back to journalism. This time she would be reporting from the Eastern Front in the First World War. Again, she was one of the only journalists to visit several enemy areas.

In 1913, she covered the women's suffrage procession for the New York Journal. Her article correctly predicted that women would not get the vote until 1920. She named her piece, 'Suffragists are Men's Superiors.'

On 27th January 1922, at age fifty-seven, Nellie died of pneumonia in a New York hospital.

She has earned many accolades and much recognition, including the annual Nellie Bly journalism award run by the New York Press.

In 1988, she was entered into the Women's Hall of Fame. In 2002 she was one of four female journalists honoured with a stamp. In 2021, a statue was unveiled on Roosevelt Island named Girl in Puzzle, commemorating her life.

Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman, aka Nellie Bly, paved the way for women in journalism and many other careers. She was a woman before her time, which may well be why I can share this article with you. I am sure you would agree she is worthy of being anyone's hero.

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe to my writing, share it and give it a heart. As a writer tips and pledges mean a great deal to me, so a massive thank you if you send one.

About the Creator

Sam H Arnold

Writing stories to help, inspire and shock. For all my current writing projects click here - https://linktr.ee/samharnold

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.