Exploring the Wreck

A story of feminine embodiment

“I came here to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.“

– Adrienne Rich. (1973)

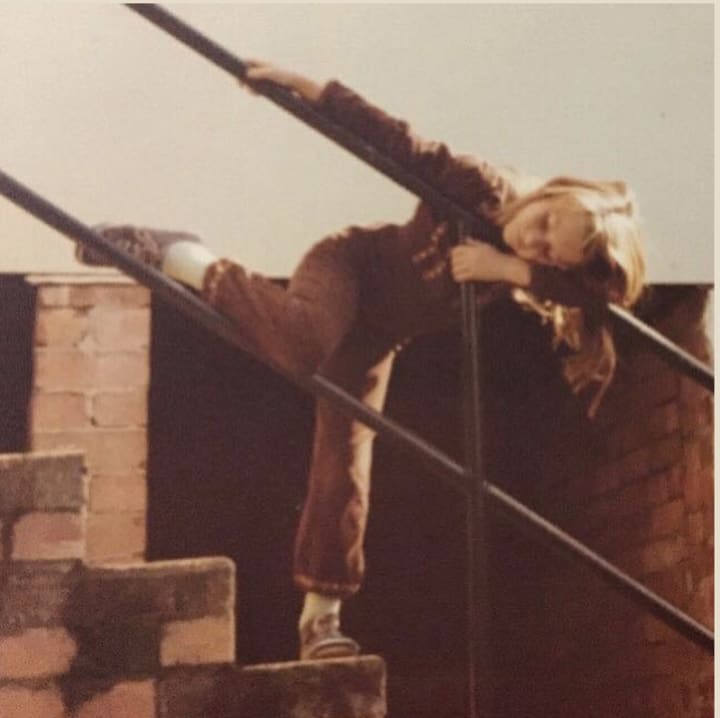

I have a photo of myself taken at around 9 years of age, lolling about on the back steps of my grandmothers house. Every time I see it, what registers most for me is how precious this moment of time was, just prior to the whole idea of having a female body being a thing to know about and to digest. It was a time of simply being embodied.

When I look back from now to then, I see a long line of situations and circumstances that seemed sent to show me that my body did not belong to me, that it was a thing that had to be regulated and maintained and subject to rules and controls lest it got out of control and become more of a problem for someone than it ought to be.

Social constructionist theorists like Erving Goffman and Michel Foucault have been highly influential in deconstructing society’s “inspecting gaze” both male and clinical, and for me that gaze arrived suddenly and unexpectedly as I carried around what felt like a powerful secret that I really didn’t know what to do with for it wasn’t mentioned in in any real way I could fathom apart from the church or the biology teacher who pointed out that my female body could now procreate and was advertising that fact like a red flag to a bull. Nor was I told that the same gaze would disappear almost faster than it arrived and that years would be spent wondering what went wrong and succumbing to consumerist ploys designed to convince me that there were ways to get it back when I was never really sure I wanted it in the first place. But the real question didn’t register till much later. What exactly was this ‘it’ that I had apparently lost and gained? What consciousness had I inadvertently entered? Feminist scholar Sandra Lee Bartky found words for those first experiences of what has now been popularly theorised as objectification.(Frederickson and Roberts 1997)

“It is a fine spring day, and with an utter lack of self-consciousness, I am bouncing down the street. Suddenly I hear mens voices. Catcalls and whistles fill the air. These noises are clearly sexual in intent and they are meant for me; they come from across the street. I freeze. As Sartre would say, I have been petrified by the gaze of the Other. My face flushed and my motions become stiff and self-conscious. The body which only a moment before I inhabited with such ease now floods my consciousness. I have been made into an object.” (Bartky, 1990)

The story of one’s body is, as Simone de Beauvoir poetically explored, “our grasp on the world and the sketch of our project” (de Beauvoir, 1949) and like the wreck of Adrienne Rich’s poem, writing this is a way of pulling up from the depths and examining, the stories society has sent me about the experience of inhabiting this female body, both the damage and the treasure.

Last year I encountered the memoir, Disappearing Acts by Rebecca Solnit. As a feminist writer, journalist and activist, her writing epitomises the “personal politics” of the body established by earlier second wave feminists. Her memoir ‘Recollections of My Non-Existence‘ (2020) is poetic, reflective and deeply personal as well as a chronicle of the continuing feminist movement and the persistence of the beauty myth in contemporary American society.

“I was convinced that my body was a failure. It was a tall, thin, white body, which is supposed to be the best thing to be in terms of how the culture as a whole values and rates female bodies. But I saw my own version of this as a catalogue of wrongness and failures and confirmed and potential shame. The rules about women’s bodies were exacting, and you could always measure your distance from the ideal, even if it was not a great distance. And even if you got over your imperfections of form, the realities of biology, of bodily functions and fluids, were always at odds with the feminine ideal and a host of products and jokes and sneers reminded you of that. Perhaps it’s that a woman exists in a perpetual state of wrongness, and the only way to triumph is to refuse the terms by which this is so….Men were always telling me what to do and how to be… to smile, to suck their dicks…what needed fixing…The problem isn’t really with bodies, but with the relentless scrutiny to which they’re subjected.” (p.79-80)

Reading Solnit, I not only understood but felt all the ways the social constructionist’s argument, that so rightly critiques the ways society ‘reads’ the body, differs from the body’s own lived experience, the state of embodiment. The ‘clinical terms‘ (p81) that men including her father used to find fault with not only her but her mother and ‘random women passing by‘, mirrors my own experience of being a young woman trying to locate myself somewhere between society’s expectations of beauty, thinness, sexiness and modesty and to please the men who whistled at me and critiqued me and compared me and ultimately chose me or not, based on how I measured up. Solnit’s story of disappearing is about becoming smaller, taking up less space physically, like Roxanne Gay meant when she wrote “we should be seen and not heard, and if we are seen it should be pleasing to men” (Gay 2017), so as to make space for the creative and intellectual life that she so craved.

“I was not trying to make myself thin…I was driven, to redeem my existence by achievement…I was like an army that had retreated to its last citadel, which in my case was my mind.”

This exploration of a diminishing bodily presence so as to escape to and cultivate the mind, reads like a reflection to me of all the ways those of us women who wish to cultivate our intelligence, and have failed in the beauty stakes, both because of and in spite of it, at least in terms of what society has viewed as appealing, have hidden, so as not to provoke or threaten the soft docility that sometimes feels expected when the objective is to please others.

“One of the struggles I was engaged in when I was young was about whether the territory of my own body was under my jurisdiction or somebody else’s, anybody else’s, everybody else’s, whether I controlled its borders, whether it would be subject to hostile invasions, whether I was in charge of myself…those altercations on the street were about men asserting their sovereignty over me, asserting I was a subject nation. I tried to survive all that by being an unnoticeable nation, a shrinking nation, a stealth nation.” (p.78)

Solnit’s landscape metaphor here invokes de Beauvoir’s claim of the body as ‘situation’ (de Beauvoir, 1949) or place, and reminds me of the ways those subtle invasions of our bodily territory can accumulate over time till we have internalised dislocation from the very flesh we inhabit. Though it is a harsh reality and perhaps (hopefully) not a current reading of the female experience, Solnit ends this particular section with words that crushed me with recognition.

“Femininity at its most brutally conventional is a perpetual disappearing act, an erasure and a silencing to make more room for men, one in which your existence is considered an aggression and your non-existence a form of gracious compliance.”

And then there was Bombshell and the whole #MeToo explosion. Though somewhat sensationalised and discredited below by the real women involved in the notorious sexual harassment scandal at Fox News that escalated the #MeToo movement in America and globally, watching this film gave me an entry point into an awareness, as I now face a working role that has more responsibility and power attached to it, of just how normalised sexual harassment and misogyny had become for me and so many women. I was affected for days afterwards and marvelled at all the ways that I and other women I know instantly excuse it, allow it or even deny that it’s happening cos we are deeply programmed not, I would say, to be inferior to men but to simply accept that some men assume that they are superior simply by virtue of their sex and that we are always, in the eyes of those same men, in competition with other women. That my currency was never my intelligence or ability but rather my physical body, had long been familiar, but in the workplace where one has worked so hard to reach a place of success and achievement, it feels all the more painful and extraordinary to be reduced to such an objectified state. And what the film highlighted for me was the deep levels of internalised self objectification I had buried within.

“Taught from infancy that beauty is a woman’s sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and roaming around its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison.” (Mary Wollstonecraft 1792)

As the real women discuss in commenting on the authenticity of the silent elevator scene up to Roger’s office, it is in the collective experience of shame, confusion and incredulity at what is happening, that gave power and force to the #MeToo movement that surrounded the scandal. In the film a confrontation is portrayed between the fictional character of Kayla, the next young bombshell and Megyn when her silence is finally broken, but as the real women so poignantly add in their response to the film, that felt clearly written by a man and not someone who had actually encountered that form of harassment, for most women implicitly understand why and how the choice to speak out is so fraught and complex. There is an implication made in this scene and others that women are somehow in competition with one another and when one of the characters in Megyn’s team at work says at one point, “god I wish I was slut-shamed” after her stand off with Donald Trump, it is clear that some misrepresentation of the actual experience of objectification and harassment has occurred and that the film, despite its power and reach, still plays into the same paradigm that the film purports to be rejecting in suggesting that there is a beauty standard and hierarchy attached to the (privilege?) of being subjected to sexual harassment. It does however highlight the theme of self-objectification that has been increasingly studied by sociologists and psychologists as an internalisation of this patriarchal gaze that appears to set the standard for many women’s experience of success and generally leaves them in a perpetual state of disempowerment.

It continues to astound me at times that even with the light that has been shone on female objectification and consequent harassment by social movements and theories around objectification and the myriad of media, film and television that is being created to attempt an address to it, that “in contemporary patriarchal culture, a panoptical male connoisseur resides within the consciousness of most women…Woman lives her body as seen by another, by an anonymous patriarchal Other.” (Bartky, 1990.)

References:

Sandra Lee Bartky, (1990) Femininity and Domination: Studies in the Phenomenology of Oppression. New York. Routledge.

Calogero, Dunn and Thompson, (2010) Self Objectification in Women, Causes, Consequences and Counteractions, American Psychological Association.

Eliana Dockterman, (2019) How Bombshell and TV Shoes Reckon with #MeToo at Work, Time Magazine.

Rebecca Solnit, (2020) Recollections of My Non-Existence,‘ Great Britain, Granata.

Susan Bordo, (1993) ‘Unbearable Weight, Feminism, Western Culture and the Body.‘ University of California.

Simone de Beauvoir,(1949) ‘The Second Sex.’ London, Vintage Press.

Adrienne Rich, (1994) ‘Diving Into the Wreck, Poems 1971-1972.‘ Norton.

About the Creator

Delaney Jane

I write teach and study religion, myth, depth psychology and dreamwork all in pursuit of the symbolic life.

http://thissymboliclife.wordpress.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.