Bettie Page and the Last Days of American Tease

The Queen of Curves and the moral panic that ended the golden age of the American pinup

Quietly and without fanfare, Bettie Page blew into New York City in the fall of 1950. Seven years later, at the height of her fame, the Queen of Curves abdicated her throne and left the same way.

Her timing was perfect. A decade earlier, her images would have been hidden under cigar shop counters while the wartime wholesomeness of Betty Grable dominated the display stands. A decade later, Page’s provocative poses seemed almost prudish. By vanishing at her beauty’s peak in 1957, Page achieved immortality. Like James Dean, her image remains frozen in time. Forever beautiful, forever young.

During her brief time in the spotlight, Page found fame twice over. She was the most sought-after model for the girlie magazines that served as the prototype for the slicker, more overtly sexual publications like Playboy that followed. She was also the poster child for a government-led backlash against the titillation of the young American male.

"I was never the girl next door."

Coney Island still attracted a crowd in October. As the memory of summer faded, New Yorkers continued to flock to the famous landmark to ride the Ferris wheel and gorge on candy floss.

In the summer, sun worshipers were packed so tightly on the beach that there was no room to lay a towel. In autumn, however, even the hardier swimmers confined themselves to the baths, which provided relative protection against the breeze blowing in from the Atlantic.

The crowds along the boardwalk were thinning out as Bettie Page wandered toward the pier. Pockets of tourists rode the Parachute Jump and the bobsled roller coaster or grabbed a bite at Atlantis Bar and Grill, but most had lost interest in the beach.

It had been more than three years since Page left Nashville to strike out on her own. Although she was only 27, she had already survived a lifetime of abuse. Her childhood was one of extreme poverty, punctuated by stints in orphanages at the behest of a mother who had never wanted daughters. Her alcoholic father sexually molested his three daughters to the point where Page expressed gratitude that, unlike Joyce and Goldie, “at least he never penetrated me, like he did the others.”

Despite her disadvantages, Page came within half a point of being valedictorian of Hume-Fogg High School. After graduation, she survived a violent early marriage to a World War II veteran who returned from the Pacific with post-traumatic stress and a penchant for threatening his young wife with his Army knife.

After walking out of the marriage, Page bounced from place to place, working as a stenographer in Haiti, playing the role of Miss Tennessee in a nightclub act in Miami, and spending a lazy summer in upstate New York, dividing her time between secretarial work at a local law office and acting with the Greenbush Summer Theater. Now she was in New York City, just in time to greet a new decade.

On Coney Island, she first laid eyes on the man who would turn her into America’s first supermodel. Jerry Tibbs had almost finished his workout when he realized the shapely brunette sitting by the boardwalk steps was watching him. Tibbs had had his eye on Page, too, although not for the usual reasons. When he finished his exercises, he walked over and introduced himself.

“Have you ever done any photographic modeling?” he asked.

Page said no; she had never even thought of it.

“You’d make a good pinup model, a photographer’s model.”

Tibbs was a Brooklyn police officer, he explained, but his real passion was photography. The two hit it off immediately and became fast friends. They shared the same qualities of confidence, charm, and good humor that overcame the strange sight of a white Southern girl in public with a Northern black man.

When Page shared her dream of making it on Broadway, Tibbs suggested a deal: If she modeled for him, he would put together a portfolio for her. He handed her a card and they made a date.

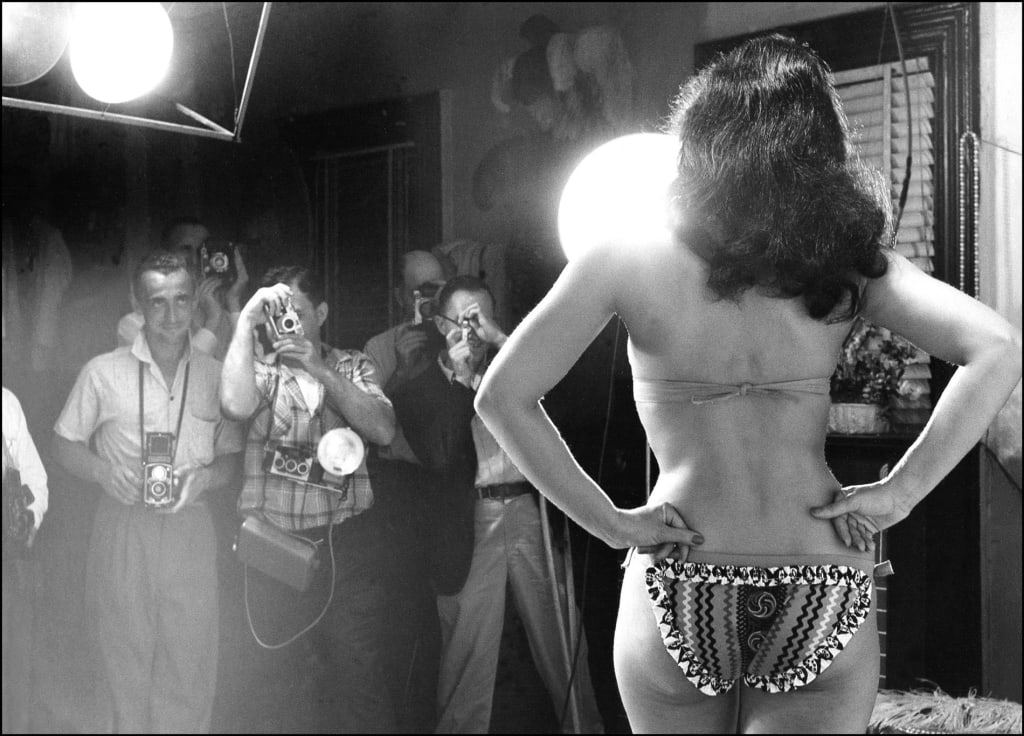

Tibbs introduced Page to the thriving camera club scene, a lucrative source of weekend income for photogenic young women. Club managers hired a model for a few hours and then charged amateur photographers $4 or $5 to join the photo shoot. Most models for camera clubs and men’s magazines were amateurs themselves, secretaries or housewives looking to make a little pin money. They earned $10 per hour for indoor shoots and $25 outdoors.

"People just called me for jobs. Just by word of mouth, from one person telling another, I guess."

Page quickly made a name for herself as New York’s most in-demand camera club model. Twice as many club members turned out for a Bettie Page shoot as for any other model. If Page lacked the exotic glamour of her European counterparts like Brigitte Bardot, she had an earthier, more American beauty. She was the actual girl next door, rather than the mythical one idealized on the silver screen. There was a hint of approachability in her trademark wink.

People responded to that accessibility. The American bachelor of the time had many passions. He loved his suits pressed sharp, his martinis shaken, and his jazz cool. He loved cars, golf, and the sight of Page between the covers of guilty pleasures with names like Titter and Wink.

Upstate farms or the sparsely populated beaches of Fire Island were frequent locations for nude shoots, which were the most popular but also the riskiest. Public nudity, even in deserted locales, was still illegal, and the United States was entering a new era of social conservatism.

In Mark Mori’s 2012 documentary Bettie Page Reveals All, Hugh Hefner, the Esquire writer who went on to create Playboy, described the atmosphere as one of profound disappointment:

Having served in World War II, which was a fight for democracy and liberation, what I expected after was something like what I perceived as the roaring twenties after World War I, a huge celebration. What we actually got was repression. Repression on several fronts. It was social, and sexual, and political.

Fear of a Communist hegemony abroad fed a moral panic at home. Traditional values were under threat from without and within. In response, federal obscenity laws were tightening, and local authorities became increasingly heavy-handed in their response to anything even loosely related to nudity or sex.

In Westchester County, New York, local police were tipped off to a nude photo shoot on a South Salem farm. In the ensuing raid, 23 photographers were arrested for disturbing the peace. Page and three other models were charged with indecent exposure. The judge issued all of them a $5 fine.

Dick Heinlein, one of the photographers arrested that day, could see that “it was an alarm to wake [Page] up to the fact that a lot of people did not like what she was doing.”

The experience led Page to focus less on the camera clubs and more on magazine shoots. Through photographers and models who freelanced with men’s magazines, Page began working for Robert Harrison, the prolific publisher of a stable of publications such as Wink, Flirt, Whisper, and Eyeful. His girlie magazines had been around since the 1930s, but they entered a boom period after the war, when paper rationing was lifted.

While the camera clubs made Page a niche celebrity, she found fame in the pages of those magazines, among articles on the “manly” working-class pursuits of hunting, fishing, and car maintenance. By 1952, she was the most popular pinup model of her time. Her nearest competition was Irish McCalla, a statuesque Californian beauty who posed for Harrison’s rival magazines Night and Day, Gala, and Focus.

“These two women,” Gay Talese wrote in Thy Neighbor’s Wife (1981), an exploration of sexuality in America after World War II through the 1970s, “were the masturbatory mistresses for many thousands of men during the postwar years.”

"I don’t know what they mean by an icon. I never thought of myself as being that. It seems strange to me."

Irving Klaw recognized opportunity when he saw it. With his sister Paula, Klaw opened up a small used bookstore in New York City. After discovering that teenagers were stealing full-page photos of their favorite film idols from magazines, he started purchasing bulk orders of glossy promotional photos from film studios. He sold them over the counter and through his mail-order business.

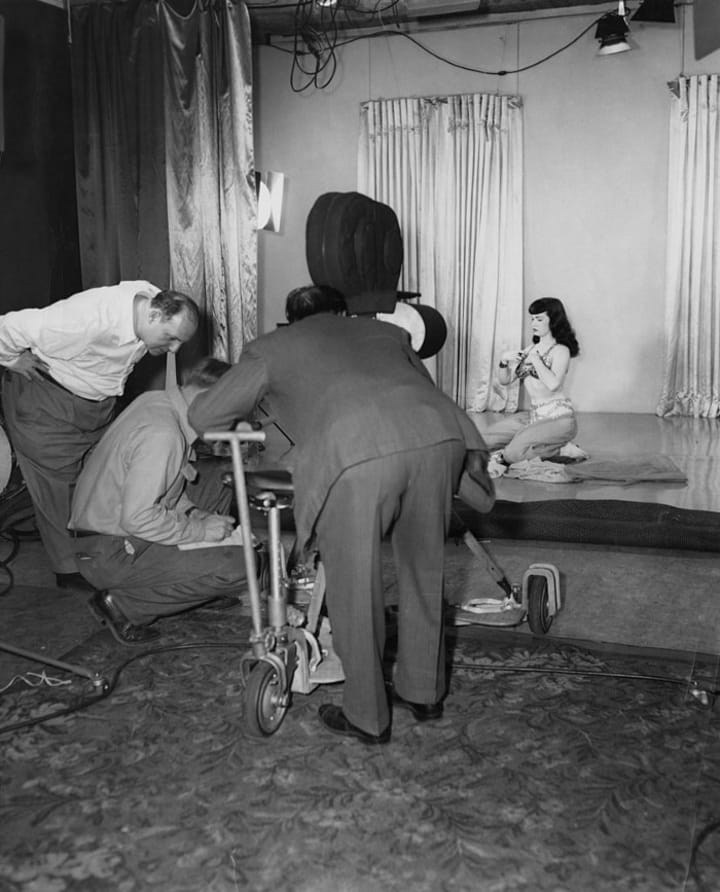

Klaw renamed the store Movie Star News, and he became known as the Pinup King. When the business expanded to include cheesecake images popularized by the girlie magazines, Klaw realized it would be more profitable to set up his own studio and hire amateur models to supply images to both his mail-order clientele and publications such as Harrison’s. Soon he had transformed a small bookstore into America’s largest distributor of movie-star stills and suggestive photographs.

Around 1947, Klaw’s reputation attracted the attention of a prominent lawyer who explained that he had some needs that Klaw and his studio could fill.

Only ever known as “Little John,” the lawyer wanted images of women in bondage, which Klaw could supply via his own studio and his discretion. The terms of the offer were too good to pass up. Little John would act as patron, covering the cost of dungeon equipment, leather outfits, model salaries, and any other expenses. Klaw would retain all rights to the photos and be free to sell copies to his mail-order customers.

Even though Page had no interest in the world of S&M (sadomasochism), she began modeling for these shoots. Klaw and Harrison’s models were part of the same circle, and most worked for both. She noted:

Irving was a real sweet fella. He was a big fat tubby guy and he was sorta short, he was almost bald, but he was so nice. He never made any passes at the women or anything. They would bring food, sandwiches and all for us. They were always very generous about that.

Alternating between whip-wielding dominatrix and rope-bound captive, Page performed a pantomime that was simultaneously spicy and kitsch—if laughably tame by today’s standards. Soon she was the number-one model for the underground bondage set served by Klaw’s soft-core mail-order business. The subterranean nature of the mail-order community meant the public never realized that America’s girl next door was also America’s dominatrix.

In stark contrast to the fetishistic images she is remembered for, Page was devoutly religious and hopelessly romantic, although she applied a certain pragmatism to her relationships with both God and men. She was similarly levelheaded in her career choices. A teacher by training, Page spent only six months in classrooms before realizing her teaching skills were no match for teenagers’ raging hormones.

“I could make more money posing in two hours than I could make all week as a secretary,” she reasoned.

In the early 1950s, the government’s definitions of pornography were fairly straightforward and relatively easy for Klaw to sidestep.

Despite close calls, particularly with the powerful U.S. Postmaster General’s office, Klaw stayed in business by refusing to shoot models naked. He also avoided involving men—and therefore the implication of sex—in any photos. His sister Paula ran every aspect of the bondage shoots, from tying up the models to directing them and occasionally standing in as photographer. Klaw even demanded that models wear two pairs of underpants so no stray pubic hairs became visible.

“For Irving Klaw,” said Page biographer Richard Foster, “no fetish was too weird as long as it didn’t involve nudity, sexual acts, or physical harm to one of his models.”

A change in public sentiment over what constituted pornography happened in 1955, a year that had begun with such promise. Klaw had expanded into burlesque cinema, bankrolling three films that were theatrically released. Page appeared in all of them. The latest, Teaserama, had come out earlier in the year to moderate success, finally providing Page with a way to transition onto the big screen.

During her regular trips to visit a sister in Florida, Page had also begun working with Bunny Yeager, one of the country’s most respected pinup photographers. Unlike the amateurs at the camera clubs or the hacks at Klaw’s studio, Yeager was talented and reputable, with access to more polished publications than Harrison’s magazines.

Yeager’s connections and the professional chemistry between the two women had landed Page a centerfold spread for Hugh Hefner’s fledgling Playboy. She was only the second Playmate to appear in the magazine. The first was Marilyn Monroe.

All that was now at risk. The country was gripped with what historian Richard Hofstadter called “the paranoid style in American politics,” where politicians advanced their careers on the back of “how much political leverage can be got out of the animosities and passions of a small minority.”

As chairman of the United States Special Committee to Investigate Crime in Interstate Commerce, Sen. Estes Kefauver applied the heat to underworld figures with names like Anthony “Tough Tony” Capezio and Jake “Greasy Thumb” Guzik. The hearings catapulted Kefauver to national recognition as a defender of public morality.

"Those pictures weren't hurting anybody. "

In 1953, the Senate established the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency as a response to growing calls to address the moral ills of the nation. Public and private hearings were scheduled across the country, focusing on media—television, comic books, magazines—that many believed were contributing to the rise of juvenile crime.

Kefauver claimed an early victory over the comic book industry, forcing companies to implement severe self-censorship measures and dragging many so deeply through the mud that it drove them out of business as the result of negative publicity or plummeting sales.

Kefauver hoped for an equally decisive victory against mail-order pornography—the term was applied more loosely and broadly than the legal definition—by taking on Klaw. If he could break Klaw, the rest of the industry would quickly fall in line.

Kefauver’s biggest weapon was one he had wielded to great success against the comic book industry. He would find a single example so impactful that its imagery would dominate the hearings. The poster child for the case against Klaw was Kenneth Grimm, a 17-year-old Eagle Scout and B-plus student. In lurid detail, the committee heard how Kenneth had been found dead and naked:

hanging in an inverted position from a stick or board suspended between the forks of two trees, and trussed up in a fashion whereby his legs and arms are tied behind him, and a rope is thrown around his neck so that he strangles himself.

Grimm’s father, Clarence, offered a detailed account of acquiring a copy of Cartoon and Model Parade, Klaw’s mail-order catalog, after his son’s death. Grimm pointed to an image of Page photographed in a similar position. The committee repeatedly implied the death was a sex-crime murder, rather than a case of autoerotic asphyxiation.

Although there was no evidence that Grimm had ever seen any of Klaw’s publications or Page’s pictures, both were implicated in the death of the teenager. Klaw and Page were summoned to appear before the committee.

In the aftermath of the total capitulation of the comic book industry to the pressures applied by the Senate hearings, it became increasingly difficult for Eric Stanton to find work as a cartoonist. To get by, Stanton went to work for Klaw, helping out with everything from setting up photo shoots to working the sales counter. He was working at Movie Star News when Page went down to see Klaw the day after the visit from Kefauver’s men.

Two of Kefauver’s men had visited Page, seeking any information that might hint at illegal or immoral activities at Klaw’s operation. They told her that Klaw was a seller of pornography and they wanted her to testify to that effect.

“No,” she said. “No way Irving ever did anything like that.” She told them that if she was forced to testify, it would be to speak on Klaw’s behalf.

Stanton couldn’t understand what all the fuss was about. “She came down to the store and had a long talk with Irving,” he recalled. “I didn’t hear what was said, but I imagine she wanted his advice.”

Page was visibly shaken by the whole affair, but Paula Klaw believed she was worrying needlessly. Although Irving had legitimate legal concerns, Paula could not see why Page—or any of the other models—had any reason to fear for their own welfare.

“All she was doing was modeling cheesecake,” Paula said. “No big thing. When the law came down on us and there was all that publicity, she got scared.”

Page feared as much for her career and reputation as for her freedom.

Against this backdrop, Klaw’s lawyer, Coleman Gangel, advised that the best strategy was to say nothing at all. Beyond confirming that he had worked as a furrier between 1933 and 1937, Klaw declined to answer any question by invoking his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

“We are not asking any quarter, nor giving any quarter, Mr. Klaw,” said a frustrated Kefauver, before citing Klaw for contempt of Congress.

"He was trying to be President, you know, and he didn't care who he hurt along the way."

A legend persisted for decades that Foley Square Courthouse was the stage of Page’s final, finest performance. Evidently, frustrated by Klaw’s refusal to answer questions, Kefauver turned on his most famous associate. As the cameras rolled, he lectured Page on the evils of pornography and the wages of sin. He denounced the corruption that Page’s employer and men of his ilk were perpetrating on the nation’s youth. By the time he finally got to a question, Kefauver was holding up an 8x10 glossy photo of Page, replete with whip, stiletto heels, and fishnet stockings.

What, the Senator demanded to know, did Page really think of wearing questionable outfits such as this?

“Why Senator, honey,” she answered in her best Smoky Mountain drawl, “I think they’re cute.”

That telling is a myth, imagined and repeated by her admirers to cast her as an empowered, elegant, defiant defender of those who wanted to do as they damn well pleased. The more mundane truth came out only when Page emerged from her 30-year exile from public view.

On the day she was set to testify, Page was left alone in a small room at the United States Courthouse for 16 hours, unable to leave and kept in the dark about what was happening.

Kefauver never called her to the stand. A court clerk eventually told her she was free to leave. The hearing was over, and so were the careers of Page and Klaw.

No Senate charges were laid against Klaw, but the resulting hysteria garnered renewed attention from state and federal authorities. Klaw spent the next decade moving the business from New York to New Jersey to Florida, continually defending new charges in court as his health declined. Decades later, Movie Star News and its catalogs of now-retro cheesecake bondage entered a renaissance, but Klaw never lived to see it.

Kefauver was once a shining light in the Democratic Party. His social conservatism aside, he should be remembered as a liberal lion. An early lead in the 1956 Democratic presidential primaries evaporated, and he was eventually trounced by resurgent Adlai Stevenson, who went on to lose the 1956 election to Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Today, Kefauver is a footnote in Democratic history. He is remembered largely for keeping the spirit of McCarthyism alive, not for championing legislation that curbed syndicated crime, corporate corruption, and racial segregation—a principled stance for a Southern politician to take.

“It’s still a very political world, the entertainment world,” says Mike Flores, the director of the 2003 biopic Bettie Page Uncensored. He continued:

Joe McCarthy is not the villain here; Estes Kefauver is. His right-hand man was Robert Kennedy, who worked with Kefauver on the hearings. These are not people that American pop culture likes to show in a negative way. And there’s the problem.

On August 8, 1963, Kefauver suffered a heart attack on the floor of the Senate. He died two days later.

The Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Justice was supposed to last for only the term of the 83rd U.S. Congress. During Kefauver’s term, it was extended indefinitely. It finally ended in 1973. In 20 years, no major legislation was ever enacted as the direct result of the committee’s investigation.

On Labor Day, 1966, a 55-year-old Irving Klaw awoke with pain on the right side of his abdomen. “Stubborn to the last, Irving decided to go to work,” rather than the hospital, said his grandson Rick, who eventually inherited the business. “Later that day, he was found dead from peritonitis.” Klaw outlived his tormentor by three unhappy years.

"I was thinking that I should quit while I was ahead. I thought they had had enough pictures of me."

Page herself lived to see the 21st century, but it was a far from ideal life. After the hearings, she spent a year or so modeling for Bunny Yeager in Florida before disappearing in 1957.

Greg Theakston, perhaps more than anyone else, was responsible for the resurgence of interest in Page from the late 1980s and beyond through his fanzine The Betty Pages. “There was this fascinating story about a woman who had reached the peak of popularity and disappeared,” he said in Bettie Page Reveals All.

Over the years, I heard a lot of crazy rumors. That she was slinging hash in Texas, that she married [movie star] Lash LaRue, that she moved to England and married a Duke, that the mob had rubbed her out because of a photo shoot gone bad, that she had passed out literature in the Chicago O’Hare airport for Billy Graham… That was the only one that was true.

Page quietly left modeling to go to Bible College with hopes of working as a missionary, only to find, after three years, that she was not welcome because she was divorced.

By 1982, living on welfare in California, Page was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and involuntarily committed to Patton State Hospital until 1992. She wasn’t aware that while she was penniless and incarcerated, a new generation of women within the punk, goth, and rockabilly subcultures had adopted her as a proto-feminist icon.

The 1950s pinups, says historian Madeleine Hamilton, should be seen in a new light and not dismissed as “simply so much eye candy”:

They were independent, often earning good money (certainly much more than most female workers), loved their own bodies, and had to be pretty tough and assertive—both in terms of hustling for work and fending off criticism from disapproving family members and the wider community. In many ways, they were the trailblazers of the sexual revolution and women’s lib movement.

Their popularity relied on what feminist film critic Laura Mulvey called the “male gaze,” the sexual objectification of women for the pleasure of a socially and economically dominant male audience. But they were, perhaps, the last generation of women to forge a life of independence out of that objectification. Just as Page was walking away, the new sexual revolution was about to begin, and it brought about a starker, darker, more blatant objectification.

Had Bettie Page and Irving Klaw’s careers peaked a decade later, they may not have stood out, but they would have survived.

In her last major interview, an 85-year-old Page lamented what the oppressive times did to her old friend and boss:

It just ruined a man and put him in bad health, and he ended up dying. I always felt, “live and let live.” Let anyone do what they want to do, as long as they’re not hurting anyone else.

I still feel that way.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.