Hiram Bithorn

The Unknown Story of Puerto Rico's first Major League Baseball Player

Growing up in Puerto Rico, I quickly became aware of the island's favorite sports: baseball, boxing and...politics (oddly enough). Many times I heard stories of the heroes and trailblazers of these fields and of their accomplishments. They became legends to be admired and revered by generations of Puerto Ricans. They get monuments and stadiums named after them to further immortalize them to the people. The first such stadium I became aware of as a kid was Hiram Bithorn Stadium in San Juan. This stadium became the host of many major sporting events and concerts. If a big-time band or pop star was coming through Puerto Rico, their show was almost certainly going to be at Hiram Bithorn Stadium. This stadium was even the "home" of the Montreal Expos for parts of the 2003 and 2004 seasons. The stadium’s history has made it one of the top prestigious venues in Puerto Rico.

This level of prestige made me think about the man it was named after. As a kid, I used to think that Hiram Bithorn, the man and ball player, must have been as legendary as the stadium they named after him. I would think that he would be held in the same regard as Roberto Clemente, arguably the island's greatest sports hero. But I eventually realized that not many talked about Hiram Bithorn or his accomplishments with the exception of him being Puerto Rico's first Major League Baseball player. Even in history textbooks, he isn't talked about at length. I'd be surprised if he even got more than a few sentences. I didn't even know that he was a pitcher. There's very little information about his life and career. I wondered why that would be the case.

So I did some research on Hiram Bithorn and found something kind of ironic; that such a historic stadium is named after a man that many (even in Puerto Rico) hardly know anything about. His Wikipedia page is about as long as the page on the stadium. The article on him at the Hall of Fame website is even shorter. I did manage to find a more detailed article on the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) website. Even this article points out how little we know about Bithorn and that many in Puerto Rico know more about the stadium than the man.

What do we know about Hiram Bithorn?

According to SABR, he was born in San Juan on March 18, 1916. He is from Danish/German/ Scottish/Spanish descent. His ancestry as well as his upbringing may have played a crucial role in his road to MLB. Bithorn had some advantages that few Latin players at the time had. First, he didn't have a Spanish sounding name; in fact, he would often be referred to as "Hi Bithorn" which arguably makes him sound more American. Second, during his childhood, Bithorn's family would often travel to the United States and his mother was an English teacher. This could have benefitted Bithorn as he wouldn't have to struggle with a language barrier as much as others and any culture shock he may have faced could have had a reduced effect or been eliminated entirely. As unfortunate as it is to say, one thing that helped Bithorn make it to the majors was the color of his skin. His ancestry being what it was, Bithorn could pass off as Caucasian to most people in the league. And true to the racial climate of the time, people (especially team owners) didn't necessarily care where he was from as long as he looks white. And if anybody asked, he was Danish/Spanish, at least according to his biographical info provided by the Cubs at the time.

Despite all this, Hiram Bithorn was not exempt from the harassment and derogatory remarks that Latin players would face almost every day. There were many in those days that would question Bithorn's "whiteness" and would gossip about him actually being a "mulatto". To these people, Bithorn needed to be "purely white" or at the very least fall under the category of "Castilian" in order to be accepted as a major leaguer. One instance of such harassment came on July 15, 1943 when Bithorn and the Cubs faced the New York Giants. Giants’ manager Leo Durocher was incessantly heckling Bithorn with derogatory terms and racial slurs which I do find ironic considering that years later Durocher would manage the Dodgers a year after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier. In any case, all accounts of the incident differ in several details with the exception of its conclusion. Bithorn had finally had enough and launched a blazing fastball, not at the hitter, but at Durocher who was standing at the dugout. By all accounts, Durocher hit the deck to avoid getting beaned and immediately stopped the heckling. For this, Bithorn gets taken out of the game, fined $25, and given a reprimand from the commissioner's office. Durocher, on the other hand, gets nothing but a scare. Although this may have been the event that put him on track of being a little more accepting of minorities as he's reportedly had good relationships with players like Jackie Robinson and Willie Mays. This incident gives me a decent insight into who Hiram Bithorn was as a person. He stood up for himself against one of the most notable managers of the time. He didn't let himself get intimidated nor did he try to hide or deny where he was from even when he could because his looks afforded him that. To me, that sums up Hiram Bithorn the person, but that leads me to my next question:

Who was Hiram Bithorn the player?

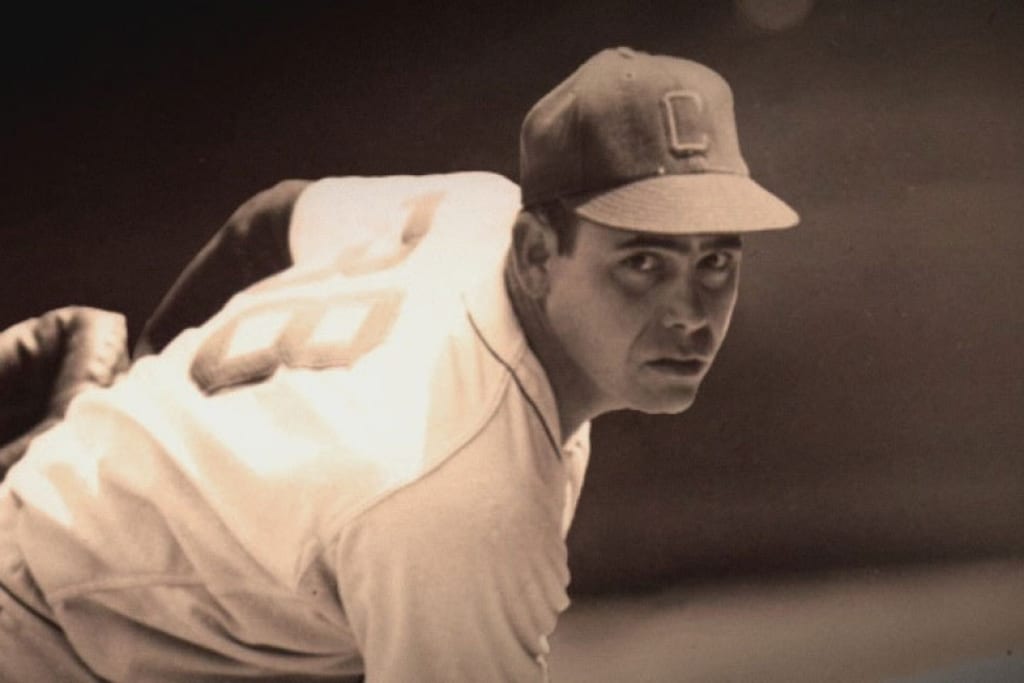

Bithorn was a starting pitcher and, according to SABR, had remarkable control along with a 90-95 mph fastball that earned him the nickname "Tropical Hurricane". Though a 90-95 mph fastball may not be anything special these days, but back then it was so much so that according to the article by SABR, Bithorn once even injured a catcher's hand at least once. Prior to starting in the majors, Bithorn was an accomplished multi-sport athlete. In 1935, Bithorn participated in the Central American and Caribbean Games and won a silver medal in volleyball and a bronze in basketball. Despite these accolades, Bithorn was already gaining popularity for his baseball prowess. In 1932, when Bithorn was 16 years old, he pitched a 10-1 victory against a visiting team from the United States that featured 19-year-old future hall of famer Johnny Mize. Bithorn's big break came in 1936 when he was invited by the Newark Eagles of the Negro Leagues to fill in for an injured starter against the Cincinnati Reds. Bithorn held the Reds to one run through seven innings before they rallied back with 3 runs in the 8th and Bithorn was relieved. The Eagles took the victory and Bithorn got the notoriety needed to break into pro baseball in the U.S. Midseason in 1936, Bithorn was finally in Class A playing for a New York Yankees affiliate the Binghamton Triplets. Bithorn would go on top spend the next 5 1/2 seasons in the minors, and every winter he would go back to play for the Puerto Rican Winter League's San Juan Senators. There, he became the youngest manager in the history of Puerto Rico's Winter League at age 22.

In 1941, the Chicago Cubs drafted Bithorn and he made his major league debut on April 15, 1942 against the rival St. Louis Cardinals. That day, Bithorn pitched 2 no-hit innings in relief. That season, Bithorn went 9-14 with a 3.68 ERA in 171.1 innings. 1943 proved to be Bithorn's breakout season as he pitched 249.2 innings with an 18-12 record, 19 complete games and a league-leading 7 shutouts. According to SABR, he became the second Latin player ever to lead the league in shutouts and still holds the season record for Puerto Rican born major league pitchers. According to Baseball-Reference, Bithorn even got a few MVP votes in 1943 finishing tied for 32nd place. By his sophomore season, Bithorn was off to a promising start. Unfortunately, the world was at war, and Bithorn got drafted into the Navy despite his request for deferment. He was inducted in November of 1943 and served two years at the San Juan Naval Air Station in Puerto Rico where he became a player-manager for the base's baseball team. Though he didn't see any combat, his years in the Navy very likely played a role in derailing his baseball career. Bithorn served in what would have been his age 28 and age 29 seasons; a time in which a ball player tends to be in his physical prime. Peak years for ball players tend to be between ages 27 through 30 and they usually set the tone for what kind of success players will have. Bithorn was finally discharged in the fall of 1945, unfortunately too late into the season to get any playing time. He ended up having an eventful offseason that winter, for better and for worse. In January of 1946, Bithorn got married and a month later, he injured his hand during a championship game in the Puerto Rican Winter League. This injury actually delayed the start of his major league season with the Cubs. Upon his return, he was assigned to the bullpen as a long reliever. He went 6-5 with a 3.84 ERA and a 1.40 WHIP. Overall, he had a decent campaign, but there were signs of decline as well as a statistical regression from his breakout 1943 season. According to SABR, there were reports that Bithorn's time in the Navy was especially challenging. At the time of his discharge, he had gained approximately 25 pounds and had a nagging arm injury. Bithorn's decline, led to the Cubs trading him to the Pirates and shortly after the White Sox claimed him off waivers. 1947 resulted in being Bithorn's last in the majors and a short one at that. He only pitched two innings in two games due to his persistent arm soreness. And just like that, Bithorn's major league career comes to close. He finished with a 34-31 record, 509.2 innings pitched, 3.16 ERA and 1.35 WHIP. Overall, his numbers are nothing to be ashamed of and, if nothing else, show the potential career Bithorn could've had if it wasn't interrupted by his military service and cut short by injuries.

Where did Hiram Birthorn go from there?

In 1947, Bithorn played 4 games for the Class AAA Hollywood Stars before finally getting arm surgery. As a result, Bithorn missed the entire 1948 season. He returned to baseball action in 1949 playing 13 games total for AA teams in Oklahoma City and Nashville. From there, Bithorn spent the 1950 and 1951 seasons playing and even umpiring in the Class C Pioneer League and the Mexican League. By 1951, at age 34, his playing days were over. Soon thereafter, Hiram Bithorn would suffer a tragic death under mysterious and bizarre circumstances.

The Death of Hiram Bithorn

For the holidays in 1951, Bithorn wanted to visit his mother and sister in Mexico. He drove his 1947 Buick from Chicago by himself since his wife was reluctant to make the trip believing it would be tough for their son who was only a few months old. According to historian Jorge Fidel López, Bithorn arrived at El Mantel and checked in to a hotel around 3 am on December 28. Later on, in the afternoon, Bithorn checked out of the hotel and soon after was confronted by a police officer named Ambrosio Castillo-Cano. The officer demanded to see the Buick's registration and then decided that whatever Bithorn had wasn't acceptable. Officer Castillo-Cano then escorted Bithorn to the local police station for an interrogation. There, Bithorn said that the car's documentation was in Mexico City. This led Police Chief Fidel Garza to order Castillo-Cano to drive Bithorn to Mexico City. As they're preparing to drive to Mexico City, Bithorn allegedly tries to escape and "fearing for his life" officer Castillo-Cano shoots him. Shortly after, doctor Virgilio Hinojosa arrives at the scene where he decides that Bithorn needs to be taken to the hospital. Bithorn is taken to a hospital 85 miles away in Ciudad Victoria. It took two hours to get Bithorn to that hospital and shortly after arriving, Bithorn passed away. Only 24 hours later, it is decided to bury Bithorn in a common grave still wearing the clothes he was assassinated in.

Once the news is out of Bithorn's murder, a myriad of questions come about as the circumstances surrounding the incident seem too weird to be true. For starters, officer Castillo-Cano claims that Bithorn was selling his car at the hotel he was staying because he needed some quick cash. Castillo-Cano also claims that Bithorn tried to sell the car without any registration or a license in his possession. These claims are suspicious because it doesn't explain how Bithorn managed to drive all the way down from Chicago, cross the border into Mexico and drive even deeper still into the country without a license and registration. Bithorn needing quick cash is also suspect since he had reportedly left home with over a thousand dollars in his possession. This amount of money, in 1951, is plenty to get you through a trip as long as this one. Not to mention, how was Bithorn supposed to get to his sister and come back home with no car? Doctor Hinojosa made the claim that Bithorn confessed to being a communist spy on an important mission and officer Castillo-Cano also went along with this claim. Not a single person that knew Bithorn confirmed this, they all insisted that Bithorn was not a communist. It could be that Castillo-Cano wanted to use the Red Scare of the 1950s as a cheap way gain hero status.

One interesting thing that came to light was that police chief Garza had instructed the owner of the hotel that Bithorn was staying at to inform him whenever a foreigner with a fancy car passes through. Chief Garza mentioned that he "wanted to buy a car at a good price." What was even more suspicious is that before it had been reported that Bithorn had gotten shot, chief Garza was spotted driving around in a Buick with no license plate. More and more this was beginning to look like a shakedown gone bad than what Castillo-Cano and company would have you believe. Ultimately, the Mexican justice system didn't buy the story but were nevertheless lenient in this case. Officer Ambrosio Castillo-Cano was found guilty of "simple homicide" and only sentenced to eight years in prison. Unfortunately, no corruption charges were brought against Chief Garza and Dr. Hinojosa was not charged as an accomplice either despite the fact that it was discovered that he refused to treat Bithorn and just decided to send him to a faraway hospital.

The injustices perpetrated by the local authorities did not stop there either. The Mexican government only agreed to give Bithorn's body back to his family after the U.S State Department intervened. Bithorn's body was returned in poor condition as he had mud all over him and there were signs of a careless exhumation. Bithorn's sister tried to reclaim his possessions and when she finally succeeded, she was given suit cases full of dirty laundry and the Christmas gifts that Bithorn had brought with him were missing. And finally, Bithorn's sister was also able to get his car back after a long, drawn-out legal fight.

Legacy

12 years after Bithorn’s death, Puerto Rico' biggest baseball stadium was named after him. His name would be immortalized and never forgotten because of the stadium's history and prestige. It's curious that his story isn't more widely known. The way I see it, this could be due to a few reasons. Back in the 1930s and 1940s, Bithorn hardly garnered fame for being a Puerto Rican ballplayer. He would often be referred to as "Castilian" which at the time was code for "yea he's Latin but at least he looks white." Not to mention, Hiram Bithorn doesn't really sound like a Latin name either. In addition to that, there's no record of Bithorn ever protesting or criticizing the omission of his Puerto Rican heritage. There's no insistence to be called by his full name or to include his maternal surname (Sosa) in anything that ever went to the public. There seemed to be an effort made around Major League Baseball at the time to change and omit anything that sounded "foreign" or Latin from players. For example, when Roberto Clemente first came on the scene, he had to insist on being called Roberto by broadcasters, writers and team staff when they wanted to refer to him as "Robert" or "Bob" Clemente. Thankfully, this kind of culture in the league is a thing of the past thanks to players like Clemente and most recently Adrián González with the "ponle acento" campaign that was successful in finally making sure that the surnames on the uniforms of Latin players had the correct punctuation such as tildes for "ñ" and accents on vowels. How Bithorn was marketed may have had an influence on how he was being perceived by Puerto Ricans. Some in the island may have felt that Bithorn wasn't representing them well enough and therefore wasn't relatable. Certainly not as relatable other Puerto Rican stars that came later like Clemente and Orlando Cepeda.

Bithorn's major league career was extremely short and in general not a very significant one. When compared to only Puerto Rican Major Leaguers, Bithorn is easily overshadowed by most of them in both longevity and statistical milestones. Bithorn's play didn't have an immediate impact on the sport, he didn't win any awards, no All-Star selections, playoff/World Series victories, and no flashes of brilliance that would have made any observer of the sport believe he was a Hall of Fame caliber player. And even if he did any of these things, there's one fact that works against his baseball merits; he played during wartime. Though he also served during the war, the majority of Bithorn's career was in 1942-43. By then, a lot of stars in the league had either been drafted or most likely had already enlisted after the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941. As a result, this diluted the level of competition that existed in Major League Baseball from '41 to 1945. Players that wouldn't normally have a chance to play or do well were now the stars of the league. With Bithorn, being a pitcher at the time, it stands to reason that he benefitted from this. Even with this benefit, Bithorn still wasn't statistically exceptional. That brings up the question, if things were different and nobody had gotten drafted or enlisted, would Hiram Bithorn be a successful pitcher? Would he have even broken into the majors? Unfortunately, these "what ifs" will never be answered, but the circumstances surrounding these questions combined with the statistical evidence point to a potentially mediocre career for Bithorn had major league baseball not been affected by the war.

Bithorn’s playing career and lack of notoriety contributes to how we know very little about him. His life was very private, not really covered by the press, and short. He died under mysterious and somewhat bizarre circumstances. His story gets further pushed into the shadows by the stories of other Puerto Rican pioneers of the sport. Bithorn's story is overshadowed by the milestones and careers of Roberto Clemente and Orlando Cepeda who debuted in MLB a few years after Bithorn's death and went on to have Hall of Fame careers. Bithorn's story also falls way short of what Clemente accomplished off the field. Clemente was a champion to the people of Puerto Rico and Latin America. He faced a double dose of prejudice and racism for being Afro-Latino. He was outspoken, stood up for himself and others like him and was an avid humanitarian. Clemente overachieved where Bithorn failed to act. To be clear, Bithorn shouldn't be blamed for apathy towards the cause of Latin players and other minorities. His philosophies, ambitions and thoughts about what a ball player can do with his platform surely differed from Clemente's. The eras in which they played were different, their backgrounds were different despite sharing a birthplace. Though both experienced difficulties for their ethnicity, one can argue that Bithorn faced less scrutiny due to the color of his skin.

Through hardly any fault of his own, Bithorn's story is mostly forgotten. His accomplishments, diminished to a footnote in the history of both the sport and the island of Puerto Rico. Bithorn opened the door for future generations of ballplayers to excel where he didn't and build on what he accomplished. Though in the grand scheme of things, his contributions are small, they are critical in making the way for legends like Clemente and Cepeda as well as the stars we see today in Francisco Lindor and Javier Báez. Baseball in Puerto Rico owes a debt of gratitude to Hiram Bithorn for paving the way for the stars that have come from the island and his story should be told. Hiram Bithorn should be remembered for more than just a stadium.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.