NFTs are causing a stir in the art world, but they have the potential to change so much more.

NFT, or non-fungible token, is a unique digital representation of a good

Jazmine Boykins was only a few months ago giving away her artwork for free on the internet. Apart from money she made selling gear with her designs between classes at North Carolina A&T State University, the 20-year-old digital artist’s dreamy animations of Black life drew a lot of likes, comments, and shares, but not much money.

Boykins, on the other hand, has recently been selling the identical pieces for thousands of dollars apiece, courtesy to NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, an emerging technology that is upending the norms of digital ownership. Artists like Boykins can earn from their work more readily than ever before because to NFTs, which are digital tokens attached to assets that can be purchased, sold, and exchanged. “I wasn’t sure if it was trustworthy or authentic at first,” says Boykins, who goes by the online moniker “BLACKSNEAKERS” and has sold over $60,000 in NFT work in the last six months. “However, it’s very amazing to see digital art being purchased at these prices.” It has given me the strength to persevere.

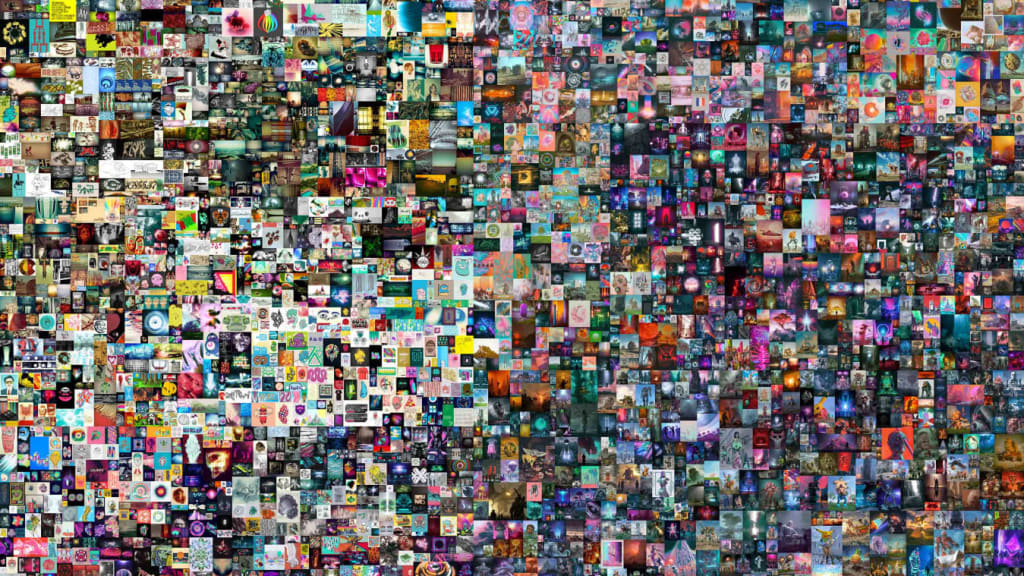

According to market tracker NonFungible.com, collectors and speculators have spent more than $200 million on a variety of NFT-based artwork, memes, and GIFs in the last month alone, compared to $250 million for the entire year of 2020. That was before digital artist Mike Winkelmann, also known as Beeple, sold a piece for a record-breaking $69 million on March 11 at Christie’s, the third highest price ever paid by a living artist behind Jeff Koons and David Hockney.

NFTs are best described as a combination of computer files and proof of ownership and legitimacy, similar to a deed. They, like cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, are stored on a blockchain, which is a tamper-proof digital public record. Cryptocurrencies, like dollars, are “fungible,” which means that one bitcoin is always worth the same as another bitcoin. NFTs, on the other hand, have one-of-a-kind valuations determined by the highest bidder, just like a Rembrandt or a Picasso. Artists who want to sell their work as NFTs must first register with a marketplace, after which they must “mine” digital tokens by uploading and authenticating their data on a blockchain (typically the Ethereum blockchain, a rival platform to Bitcoin).

At first glance, the entire operation appears absurd: wealthy collectors paying six to eight figures for works that are frequently viewed and shared for free online. The NFT art craze has been regarded by some as just the next bubble, similar to this year’s boom-and-bust enthusiasm around “meme stocks” like GameStop. Not only artists and collectors are drawn to the phenomenon, but also speculators hoping to profit from the latest craze.

It could be a bubble. However, many digital artists have jumped headfirst into the trend, fired up with years of creating work that generates traffic and interaction on Big Tech platforms like Facebook and Instagram while receiving absolutely nothing in return. Now that it’s possible to truly “own” and sell digital art for the first time, these artists of all kinds — authors, singers, and filmmakers — see a future in which NFTs revolutionize both their creative process and how the world perceives art. “You’ll have a lot of people from all various backgrounds and genres coming in to express their creativity, make connections, and possibly establish a career,” Boykins says. “Artists invest so much of themselves — and their time — in their art.

Digital art has long been underappreciated, in part due to its accessibility. NFTs add the key ingredient of scarcity to help artists build financial value for their work. Some collectors are more likely to seek out the “genuine” piece if they are aware that the original version exists. Scarcity is one of the reasons why baseball card collectors are ready to pay $3.12 million for a piece of cardboard with a picture of Honus Wagner, a renowned Pittsburgh Pirate. It’s also why sneakerheads swoon over Nike and Adidas’ latest limited-edition releases, and why “pharma bro” Martin Shkreli paid $2 million for the only copy of Wu-Tang Clan’s Once Upon a Time in Shaolin in 2015.

Baseball cards, sneakers, and that Wu-Tang CD, on the other hand, all exist in the tangible world, making it easy to comprehend why they’re valuable. It’s not always clear why digital art, or any other digital file, is valuable.

Some collectors of digital art claim to be paying not just for pixels but also for the labor of digital artists, implying that the movement is part of an effort to monetarily legitimize a burgeoning art form. “I want people to go through my collection and think, ‘Oh, these are all unique things that stand out,’” says Shaylin Wallace, an NFT artist and collector who is 22 years old. “The artist put a lot of effort into it, and it got the price it merited.” After spending the majority of the previous year online, the movement is also taking shape. It makes sense to spend money on virtual items when practically your entire environment is virtual.

CryptoKitties — think digital Beanie Babies — launched in 2017 and established the framework for the digital-art boom. Fans have spent more than $32 million on these wide-eyed, one-of-a-kind cartoon cats, which they have collected, traded, and bred. In the meantime, video gamers have been splashing cash on aesthetic improvements for their avatars, with Fortnite players spending an average of $82 on in-game stuff in 2019, further mainstreaming the idea of spending real money on digital products. At the same time, the value of cryptocurrencies has soared, propelled in part by celebrity supporters such as Elon Musk and Mark Cuban. Bitcoin, for example, has increased by more than 1,000 percent in the last year, and anything even crypto-related, including NFTs, has been caught up in the frenzy.

Duncan and Griffin Cock Foster, tech entrepreneurs and brothers, saw an opportunity and founded Nifty Gateway, an NFT art marketplace, in March. NFT art was gaining popularity in some circles at the time, but it was difficult for newcomers to acquire, sell, and trade pieces. Nifty Gateway put accessibility and usability first, which helped it gain traction. “We didn’t have many expectations about how it would turn out because it was so early,” Duncan Cock Foster explains. However, in its first year, Nifty Gateway customers purchased and sold more than $100 million in art. Similar platforms, such as SuperRare, OpenSea, and MakersPlace, have seen similar increases, with 10 percent to 15% of early sales going to them.

Big corporations and celebrities are joining in the fun: According to parent firm Dapper Labs, NBA Top Shot, the NBA’s official platform for buying and selling NFT-based highlights (packaged like digital trading cards), has racked up over $390 million in sales since its October launch. NFT trade cards featuring Super Bowl highlights were sold for over $1.6 million by football star Rob Gronkowski, while NFT music was sold for almost $2 million by rock band Kings of Leon. Jack Dorsey, the founder of Twitter, has put his first tweet up for auction as an NFT, and it’s anticipated to fetch at least $2.5 million. The last two months have been a feeding frenzy, with new highs appearing on a near-daily basis. After his world-record-breaking auction, Beeple said it best:

The biggest deals in the world of NFT art are made by so-called whales. These wealthy investors and cryptocurrency evangelists stand to profit handsomely from promoting anything related to cryptocurrency. “A Winklevoss spending 700 grand on a Beeple or whatever is very much marketing spend for an idea that they are heavily invested in,” says Mat Dryhurst, a technologist and artist. He’s referring to Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss, two well-known cryptocurrency bulls who bought Nifty Gateway for an undisclosed sum in late 2019.

Daniel Maegaard, an Australian crypto trader who claims to have made a $15 million fortune when Bitcoin’s value skyrocketed in 2017, is one of those whales. Maegaard has amassed a fortune in digital art and other NFT-based assets, including a $1.5 million plot of land in Axie Infinity, a virtual cosmos. While Maegaard initially regarded NFTs as a way to increase his fortune, he has since grown to love the work, proudly exhibiting his collection online and sharing news of new acquisitions and sales with his followers. He’s particularly fond of CryptoPunk 8348, an image of a pixelated man who looks vaguely like Walter White from Breaking Bad.

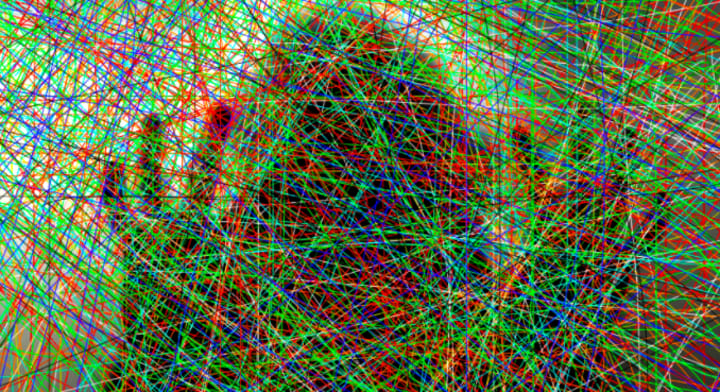

Investors who view NFT art merely as an asset to be bought low and sold high, on the other hand, are putting money into the pockets of artists. For years, Los Angeles-based artist Andrew Benson has experimented with psychedelic, glitchy digital video work. He’s gotten his art into museums and galleries, but to make ends meet, he’s worked at a software business and done commission work for musicians like M.I.A. and Aphex Twin. “I’ve always believed that the greatest way to live as an artist is to not have to survive as an artist,” Benson adds.

Benson was tormented with worry about his future in the art world a year and a half ago, when his plans to present a new series of videos fell through. He recalls wondering to himself, “Do I even want to go through the hassle of attempting to do this kind of work and finding somewhere to present it?” In January, a friend who works at Foundation, an NFT platform, encouraged Benson to submit a piece. Benson didn’t think much of it, but he did send along a video that he says would have otherwise “gone on a website or something.”

The piece, which resembles a kinetic, multicolored Rorschach, sold for $1,250 in just ten days. Benson has since sold ten more paintings in the similar price range. He’s now considering a future in which he could only rely on his art to support himself. “Actually, it kind of shook my worldview,” he says. “Watching this work find a context and a location where it matters encourages me to think more like an artist.”

NFT collectors are also showing a strong interest in many other artists who work in avant-garde and occasionally controversial approaches. Hyper-referential (and often vulgar) cartoons, as well as spinning 3-D renderings, street-style oversaturated color schemes, and hyper-referential (and often crass) art, are all prospering. Both a younger demographic raised on Instagram and a rabble-rousing crypto clientele are drawn to these Internet-fueled styles. “Street art and countercultural trends are being exploited to support the notion that most finance-crypto people have that they are ‘punks’ in the greater tech and finance sector,” adds Dryhurst.

Many in the traditional art world are stunned by these changes. “A lot of traditional collectors look at the NFT space and can’t seem to fit it into any acceptable system of belief,” says Wendy Cromwell, an art adviser in New York. “We’re at a critical juncture: many of the most knowledgeable people in the art world are getting older and don’t have the interest or mental capacity to decipher the Internet’s jargon.” Following Christie’s Beeple sale, rival auction house Sotheby’s swiftly announced its own collaboration with NFT artist Pak, demonstrating that, while art powerhouses may not grasp the genre, they do appreciate its lucrative potential.

A new generation of digital artists is grouping together in tight-knit NFT groups, with or without the approval of the establishment, mirroring previous generations of artists spanning disciplines and genres hanging out and influencing one another’s ideas, approach, and production. “In the place, there is a big ethic of kindness,” Benson explains. “In the worlds of independent music and fine art, it’s common to believe that one artist will emerge victorious from a scene. There’s a sense of abundance with this, and it appears like everyone may gain.”

Even if the NFT craze benefits artists, collectors, and speculators, it is not without its drawbacks. Some creators may be put off by the barriers to entry, which include the fact that selling an NFT costs money and necessitates technical knowledge. Many people are concerned that young artists of color, who have long been marginalized in the “conventional” art industry, may be left out. Because some artists’ work has been reproduced and sold as an NFT without their permission, legal experts are trying to figure out how existing copyright rules will interact with this new technology. “It’s giving people another platform to take advantage of other people’s work,” says Connor Bell, an artist whose work was plagiarized and uploaded on an NFT marketplace.

Then there are the environmental concerns. Creating NFTs requires an enormous amount of raw computing power, and many of the server farms where that work happens are powered by fossil fuels. “The environmental impact of blockchain is a huge problem,” says Amy Whitaker, an assistant professor of visual arts administration at New York University, though some cryptocurrency advocates argue these fears are overblown.

Climate-conscious artists may theoretically switch to a blockchain platform that has a lower environmental impact. They’re already thinking about new ways to use NFT technology for good. Some, for example, are setting up their tokens such that they are reimbursed if their work is resold, similar to way an actor receives a royalty check when a rerun of their show airs. Bitmark, a Taiwanese digital startup, has launched an NFT-style platform to distribute rights and payments to music producers all around the world. In contrast to existing digital giants like Facebook and Instagram, artists who join NFT-based social media sites like Friends With Benefits gain partial ownership in the platform and can receive direct compensation for the work they create through the network.

Meanwhile, the NFT frenzy is merely another proof of technology evangelists’ long-held convictions that cryptocurrencies, and blockchain platforms in general, have the power to change the world in significant ways. Blockchain technology has previously been used to improve vote security in Utah, combat insurance fraud at Nationwide Insurance, and safeguard medical data at a number of U.S. health-care organizations. It could also help corporations assure supply chain transparency, improve mutual aid efforts, and minimize biases in historically racist loan-application processes, according to supporters.

10K Collection Minting Now.Whitelisted

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.