Tit for tat.

How Germany humiliated France in WWII for shaming them in WWI

This is the story of Wagons-Lits Co. carriage 2419D, which went from serving sauteed veal and boeuf bourguignon to passengers in the seaside town of Deauville to serving as a crucible for world peace while stopped in the middle of a forest in Compiegne.

On 11 November, 1918, after over 17 million dead, the Great War, or as it came to be known later, the First World War came to a bloody end. The Axis powers were defeated. Austria, Hungary and the Ottoman Empire had already capitulated and signed armistices. The German monarch, Kaiser Wilhelm II had abdicated to the Netherlands following a revolution, and a new Weimar Republic, sworn in on 3rd October, was eager to bring an end to the losing war.

And thus, the armistice was the result of a hurried and desperate process. The German delegation headed by Matthias Erzberger crossed the front line in five cars and was escorted for ten hours across the devastated war zone of Northern France, arriving on the morning of 8 November 1918. They were then taken to the secret destination aboard Ferdinand Foch's private train parked in a railway siding in the forest of Compiegne for negotiating the terms of surrender.

Why such a humble setting instead of a glittering palace or a grand military building in a show of might and superiority like the US would do almost three decades later with the Japanese on the USS Missouri?

Ideally, the official headquarters in Senlis of the Allied commander, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, would have been the expected place to sign a cease-fire. But the town had endured a brutal German assault. Its inhabitants were taken hostage and its mayor shot in September 1914, before the first Battle of the Marne. How the bruised townspeople would react to the presence of a German delegation, even one coming with the goal of peace, was a serious concern.

A moveable train carriage in the nearby Compiegne forest was deemed ideal: The isolated location would deter intruders and the calm and secrecy offered a measure of respect to the defeated Germans. As it happened, Foch had fitted out a mobile office just the month before — a dining car chosen at random from the French passenger train fleet. And so 2419D became known as the "Wagon of Compiegne."

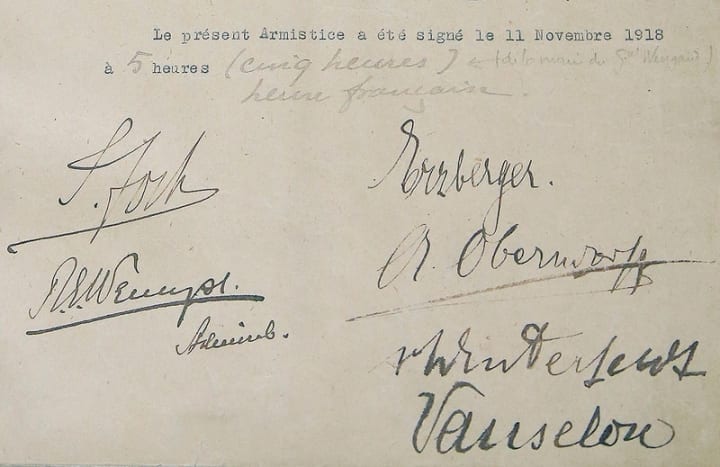

The Armistice was signed three days later, just after 5 a.m., but officials held out six hours to put it into effect out of a sense of poetry — the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918. That delay, rather unpoetically, cost lives on both sides at the end of a war that had already left 17 million dead.

For the Allies, the train car represented the end of fighting. The end, when people found peace. The carriage was taken to Paris for display in the courtyard of the Invalides, the final resting place of Napoleon, before it went back to Compiegne in 1927 to sit in a specially-made memorial. For throngs of French mourners in the post-war years, the dining car became a shrine to peace and catharsis. The wagon received over 190,000 visitors in one year alone in the 1930s as it became a focus for mourning France's 1.4 million fallen soldiers.

For the German people though, the carriage struck a raw nerve. At the end of WWI, Germans could hardly recognize their country. Up to 3 million Germans, including 15 percent of its men, had been killed. Germany had been forced to become a republic instead of a monarchy, and its citizens were humiliated by their nation’s bitter loss.

Even more humiliating were the terms of Germany’s surrender. World War I’s victors blamed Germany for beginning the war, committing horrific atrocities and upending European peace with secretive treaties.

But most embarrassing of all was the punitive peace treaty Germany had been forced to sign. The Treaty of Versailles didn’t just blame Germany for the war—it demanded financial restitution for the whole thing, to the tune of 132 billion gold marks, or about $269 billion today. Allied victors took a punitive approach to Germany at the end of World War I. Intense negotiation resulted in the Treaty of Versailles’ “war guilt clause,” which identified Germany as the sole responsible party for the war and forced it to pay reparations. Reparations further strained the economic system, and the Weimar Republic printed money as the mark’s value tumbled. Hyperinflation soon rocked Germany. By November 1923, 42 billion marks were worth the equivalent of one American cent.

The Treaty was a series of humiliations targeted at Germany and its people. Germany was forced to concede the coal mines of Saar Basin and Alsace-Lorraine to France. The Rhineland was demilitarized. Austria was made independent. Former territories were given away to Czechoslovakia, Poland and Austria-Hungary. Germany had give up all of its colonies in Africa and China. The military was basically neutered. The army was reduced from 1.9 million to 100,000. The navy was reduced to a skeleton and the air force abolished.

Humiliation led to bitterness. Bitterness led to anger. This resulted in the stab-in-the-back legend, which attributed Germany's defeat not to its inability to continue fighting (even though up to a million soldiers were suffering from the 1918 flu pandemic and unfit to fight), but to the public's failure to respond to its "patriotic calling" and the supposed intentional sabotage of the war effort, particularly by Jews, Socialists, and Bolsheviks. Matthias Erzberger, the German delegate at the armistice was labelled as a traitor by many on the Right for signing the cease-fire, and eventually led to his assassination in 1921.

The Treaty of Versailles thus turned the Germans against the Allies and in a way, played a crucial role in the buildup to WW2. Ferdinand Foch’s carriage stood out as symbol for everything wrong with the surrender terms. For Hitler, it became a rallying cry during his ascent to power as he exploited the German public's contempt for the punitive terms of surrender.

Then, two decades later, WW2 happened.

In May 1940, in a daring offensive, the newly formed, highly trained Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe, propelled by its earlier success of blitzkrieg-ing Poland smashed into Belgium and Holland. A few days later, Hitler’s forces emerged from the Ardennes, which the Allies thought to be impenetrable by tanks. Thus began a game of flanking and counterattacks, with the Panzers cutting off Allied supply lines, pushing the Allies to the Channel coast, paralyzing their high command and eventually driving out the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk. Then, in the second act, the Germans struck south. In June 14, the German forces entered Paris, now declared an open city, a little more than month later than the offensive started. On June 22, France surrendered to Germany.

Hitler had visited the carriage at its memorial in Paris when his armies conquered France. The Fuhrer ordered the dining car brought out of the memorial and returned to the tracks in the spot in the forest it occupied in 1918.

What ensued was Hitler's surreal theatrical re-staging of the 1918 armistice, one of history's most famous events, with literally the tables' turned. The 1940 Armistice was dictated in that train — with Germany the victor and France the loser.

And that is how Hitler got his sweet revenge against France for Germany’s degradation in WWI.

Hitler then ordered the car to be hauled to Germany and displayed, like a notorious prisoner of war, at the Berlin Cathedral. The dining car was destroyed at the end of World War II, though how that happened has been lost to time. Some accounts blame members of the Nazi SS, others a random airstrike.

About the Creator

Diptangshu Karmakar

Medical student. Certified nincompoop. Questionable bookworm and painter. Common sense: defenestrated. Interested in anthropology, evolution and history, especially military.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.