This Is The Great Fire Of London 1666 Story

Those who survived the Great Plague of 1665 must have thought that the year 1666 could not have been worse! Poor souls… they could not have imagined the tragedy that was about to fall on them.

On September 2, a fire started in the King's bakery in Pudding Lane near London Bridge. This rapidly spread to Thames Street, where warehouses packed with combustibles and a heavy wind from the East turned the blaze into an inferno. After days of struggles, the Great Fire was finally extinguished on September 6. By then, more than four-fifths of London was ashes. Miraculously, Only around half a dozen people were recorded to have died.

Sunday, September 2, 1666

Thomas Farriner Pudding Lane bakery is now almost one o'clock on Sunday, September 2. Everything's quiet in Pudding Lane. The foreigners finally had gone to bed. The 23-year-old daughter Hannah was the last to go to sleep after getting in light for a candle.

Later the Farriner would insist that everything was absolutely normal when Hannah went downstairs at midnight and that the fire in their oven was definitely out. But they would say that, wouldn't they?

We now believe the most likely cause of The Great Fire was a stray ember that ignited a pile of twigs stored in a bakehouse. Unnoticed, it started to take hold.

Thomas Farriner, the teenage son and apprentice, also called Thomas woke up. He realised the ground floors were on fire and immediately woke up his family sleeping upstairs. Trapped by the smoke, their only escape route was to crawl out of an upstairs window and onto a neighbour's roof, raising the alarm at the tops of their voices. This corner of London sprang into life as people around Pudding Lane realised they were facing their most terrifying enemy: Fire.

The fire began to spread incredibly quickly, and within minutes it had moved from the bakehouse to other parts of the building, with sparks even leaping towards the houses next door.

Why would the fire go on to consume the buildings around Pudding Lane so rapidly?

Jettying created more space inside a house without obstructing the street below. However, it did mean that buildings were dangerously close together.

In London, we would have had a street at the bottom, wide enough for a car or a wagon, but you could probably shake hands with your neighbour at the top. With the tops of the houses packed so tightly, the fire around Pudding Lane could quickly jump from jetty to jetty from roof to roof.

In the 17th century, many of the city's walls were made using wattle and daub.

These were woven wood panels known as a wattle which was then filled with a mud mixture (the daub). But it was this method of construction that actually helped the houses around Pudding Lane to ignite.

Many buildings in the more deprived areas where the fire started were not brilliantly maintained, exposing the wooden wattle behind the daub.

The houses around Pudding Lane were in a similar state of disrepair, making them all highly flammable. It was only a matter of time before the fire destroyed them.

Of course, there'd been fires in London before 1666.

Fires were quite common.

Londoner's reactions firstly don't seem to have been that bothered. We know that from the great commentator on the fire Mr Samuel Pepys. I love Samuel. The greatest account of the Great Fire of London. He says that Jane, his maidservant, had woken him up at about three o'clock in the morning and said there was a fire in the city. He had a look out of the window besides, it wasn't too bad, and went back to bed.

Samuel Pepys, like many other Londoners, were probably thinking that all would be well. Still, they hadn't counted on how incompetent the mayor Thomas Bloodworth was.

In the small hours as the fire was beginning to take hold, Bloodworth had one last chance to save London before the inferno became unstoppable. But he blew it.

He could have pulled down private houses, created a fire break, but those houses belong to wealthy merchants who'd put him in power, and he didn't want to be unpopular. Instead, he said a woman could piss it out.

Terrible decision because it means he's remembered for that dodgy joke instead of putting out the Great Fire of London. Well done, Thomas Bloodworth!

As dawn broke, London was in utter chaos.

Most people had stopped trying to put out the fire and were now desperately scrambling to save themselves and their things. Forget community spirit now; it was every man, woman and child for themselves. The writer Samuel Pepys takes a boat along the Thames, and he notices the fire seems to be carried on the wind is killing the pigeons that Londoners keep the food. Samuel Peeps, in his diary, writes:

"And among other things, the poor pigeons, I perceive, were loth to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconies till they were, some of them burned, their wings, and fell down."

We know that other writers commented on the same thing: strong winds and the unusually hot, long, dry summer. But none of them realises that these conditions were creating the perfect opportunity for wildfire. Even with today's state-of-the-art equipment, a fire backed by a strong wind can be a nightmare scenario for any firefighter.

Total chaos reigned as thousands watched the tragedy unfolding.

Samuel Pepys, a clerk of the Privy Seal, rushed off to inform King Charles II. The King immediately commanded that all the houses in the fire route be pulled down to create a 'fire-break.

By September 4, half of London was in flames. The King himself joined the fight against the fire, carrying buckets of water to stop the fire.

The Royal army was called in.

Flames reached St. Paul's Cathedral. The acres of lead on its roof melted and flowed down like a river into the street, and the great Cathedral collapsed. The Tower of London got away from the inferno, and ultimately, the fire was brought under control. By September 6, the fire had been extinguished altogether.

But only one-fifth of London was left standing!

The Great fire left hundreds of thousands of people homeless. Eighty-nine parish churches, the Guildhall, several other public houses, gaols, markets, and fifty-seven halls were burned-out shells. The loss was assessed between £ 5 and £7 m. King Charles gave a generous purse of 100 guineas to the firefighters to share. Not for the last time would the nation honour the bravery of its key workers.

In this mad panic Londoners cast the net widely for someone to blame.

Against all common sense Thomas Farriner, the baker from the Pudding Lane area, is not the first to be accused, and when he finally has to answer for himself, he quickly points the finger at someone else. Thomas Farriner turned out to be a master at passing the buck.

You can imagine his delight when the authorities began turning up the heat on a 26-year-old watchmaker's son from Normandy called Robert Hubert.

Hubert was French. He claimed to be Catholic, and like many terrified foreigners, he was fleeing the country when he was caught. None of that voted well, but the thing that damned him was that he confessed when asked about who started the Great Fire of London.

It wasn't long before Robert Huber was on trial and facing the death penalty. And Farriner was off the hook.

Amazingly a record of who bears trial still exists. It's kept at the London Metropolitan Archives.

The original trial's record against Robert Hubert says:

Robert Hubert lately of London a labourer, diabolically, voluntarily maliciously and feloniously started the great fire by putting a fireball through the window of a bakery in Pudding Lane.

Why did he confess?

Well, this is where the story becomes quite sad and a little tragic. Robert Hubert was someone who was mentally unbalanced and it's very likely that he did it for attention.

But if at a distance of 350 years we can judge that he probably wasn't in a fit mental state to give a confession like this, why do they believe him? Really, they were looking for someone to blame and also there was another figure who stood to gain by this confession. Thomas Farriner, Thomas Farriner jr. so the whole Fairness family testified against him. So they're behind this miscarriage of justice. They really are the Baker's from hell.

Robert Huber paid the ultimate price and was hanged at Tyburn Gallows on the 29th of October 1666.

While the Great Fire was a tragedy, it cleansed the crowded, disease-ridden streets, and a new London appeared. A monument was raised where the fire started and can be seen today in Pudding Lane, a reminder of those horrific days in September 1666.

Sir Christopher Wren took the reconstruction task. His masterpiece, St. Paul's Cathedral, was started in 1675 and completed in 1711. There is an inscription in the Cathedral in his memory, which reads, "Si Monumentum Requiris Circumspice". – "If you seek his monument, look round".

Wren also reconstructed 52 of the City churches, and his work transformed the City of London into the place we all recognise.

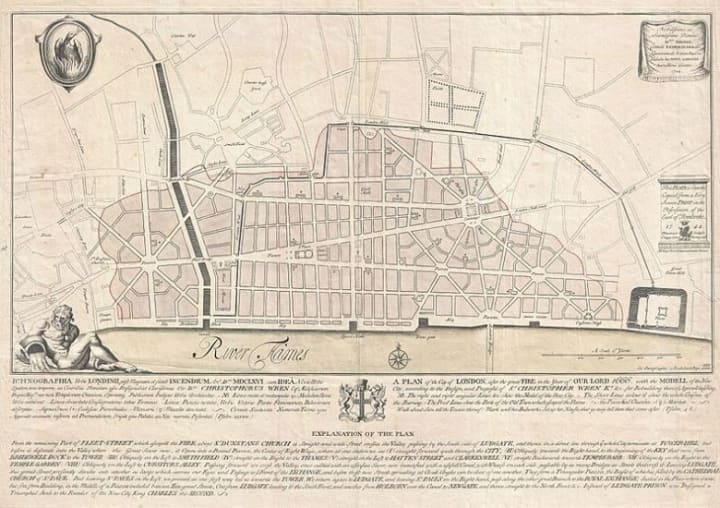

The map above, said to be a replica of the original, shows Sir Christopher Wren's proposal to rebuild the city after London's Great Fire. Notice on the lower left-hand side an image of Thames is the river god after whom the Thames is named.

The mythical phoenix on the upper left-hand side indicates that London will rise from the ashes too.

About the Creator

Anton Black

I write about politics, society and the city where I live: London in the UK.

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insight

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.