Dr. Ford: the “Perfect Victim”

Even before Dr. Christine Blasey Ford began her testimony, it was clear she was the “type” of sexual assault survivor who had a good chance of being heard. White, highly educated, successful, blond, large-terrified eyes – she appeared on the screen as an embodiment of white middle class femininity (endnote 1). Then, as she started her opening statement, a soft-spoken and girlish voice emerged from this grown woman. As her hearing continued, her demeanor was consistently deferential. Nothing about her was “threatening.” She performed and capitalized on her social position, embodying white middle-class respectability and feminine passivity. She was at once credible and infantile – the “perfect victim” for Congress to “rescue.” For a split-second, I thought Kavanaugh was doomed.

I was wrong. Confirmed shortly after, Kavanaugh’s successful appointment affirmed white patriarchy’s salience in the United States.

This paper analyzes the gender ideologies and language ideologies that constructed Ford as what I call the “perfect victim” (endnote 2): a survivor who gains power and legitimacy by upholding a white middle class feminine identity, speaking with deference, and overall posing little direct threat to white patriarchy. First, I outline the advantages Ford was assured simply because of her white and professional status, referencing the ways Anita Hill experienced a different public reception. Second, I explore the ways Ford employed “Women’s Language,” indexing her white middle class femininity. Third, I examine why women employ linguistic strategies that paint them as “powerless,” considering how women gain social power by reenacting the oppression of their gender. Fourth, I interrogate whether strategic use of “powerless” language is a form of resistance against or complicity with white patriarchy. To conclude, I discuss the importance of building meaningful solidarity between white women and women of color. If white women want to be "allies" to women of color, we have to address the ways our daily actions – even our speech – reproduce a white patriarchal order. Kavanaugh’s confirmation has brought into focus how urgent this task is.

The “Perfect Victim” is White and Middle Class

As an upper class white woman, Ford had a higher chance of being heard than woman of color and lower class woman. Early on, she was established as an educated, “respectable” figure. Senator Feinstein’s opening introduction painted a clear picture. Announcing, “…when I saw your CV, I was extremely impressed,” Feinstein highlighted Ford’s extensive academic achievements: attendance and employment at multiple elite institutions; a long list of peer-reviewed article publications; and “numerous awards” (Washington Post Transcript, 6-7, endnote 3) . She then added, “[If] that were not enough,” Ford is a “wife” and “mother” (Washington Post Transcript, 7). Ford is the “complete package;” as a professional woman who continues to perform traditional feminine roles, she does not transgress middle class norms and values. Following Feinstein’s introduction, Ford’s opening statement gave us additional insights about her racial and class status. We learned about a woman who grew up in a suburb, attended a private all-girls school, and spent summers at the “country club” (Washington Post Transcript, 11). Later in life, she had access to professional counseling as well as “completed a very extensive, very long remodel” of her home (Washington Post Transcript, 13). Ford is the “perfect victim” because a professional class white woman could not deserve, ask for, or lie about sexual abuse. Overall, Ford’s whiteness and class status bolstered her visibility and credibility in the eyes of Congress and the mainstream American public. As Tambe (2018) points out, “popular media coverage” of #MeToo has highlighted a “familiar problem in a racist society:” “[middle class] white women’s pain” is centered over and above other women’s struggles (199).

In contrast, as Mendoza-Denton explains, Professor Anita Hill’s social position was a significant disadvantage during her 1991 hearings. Although, like Ford, Hill was highly educated and professionally successful, she was a Black woman – subject to both sexism and racism. As a woman, she could easily be dismissed as “[emotional]” and “[hysterical]” (Mendoza-Denton, 62). However, she was also up against racist stereotypes that labeled her as “verbally and sexually aggressive” (Mendoza-Denton, 62). Before she had a chance to speak her truth, she was already the “angry Black woman” as well as the “promiscuous” “Jezebel” (Mendoza-Denton, 63). To make her position more complex, she had accused a Black man of sexual misconduct – evoking a history of Black men being lynched for unfounded rape accusations (Mendoza-Denton, 63). The Black antiracist community was “highly suspicious” of Hill, opting to “[rally]” around Thomas (Mendoza-Denton, 62-64). Hill was able to align herself with the (largely white) feminist community, but these “supporters” marginalized her Blackness (Mendoza-Denton 63-64). The arguments of (white) feminists failed to consider the specifics of Hill’s situation – such as the pressure on Black women to protect Black men (Mendoza-Denton, 63-64; Tambe, 199-200). Unlike Ford, Hill had to navigate being female and Black; she did not have access to the image of white respectability Ford so easily conjured. Up against stereotypes and expectations particular to Black women, Hill’s credibility was compromised among the mainstream American public and the Black community.

As a result of their different social positions, Hill and Ford had differential access to a white middle class feminine speech style. Hill was ultimately left with few linguistic options. An emotional testimony would be read as the aggressive; use of African American English would be read as masculine and improper (Mendoza-Denton, 62). She had “no choice but to adopt a dispassionate and clinical speech style” (Mendoza-Denton, 62). Speaking like a “white woman,” Hill was perceived by the both white and Black Americans as “insincere,” “cold,” and “calculating” (Mendoza-Denton, 62-63). Ford, on the other hand, was received differently. She could speak “white” without compromising her credibility. So long as she stuck to the narrow script associated with her white middle class femininity, Ford could construct herself as a believable and unthreatening victim. Whereas Hill’s “white woman” performance resulted in disapproval and disavowal, Ford’s “white woman” performance was a source of power.

In what follows, I discuss ways Ford embodied “traditional” femininity through speech. I then explore why her testimony was compelling, examining how performing “powerlessness” can reflect agency yet reinforce existing power inequities.

The “Perfect Victim” is Deferential

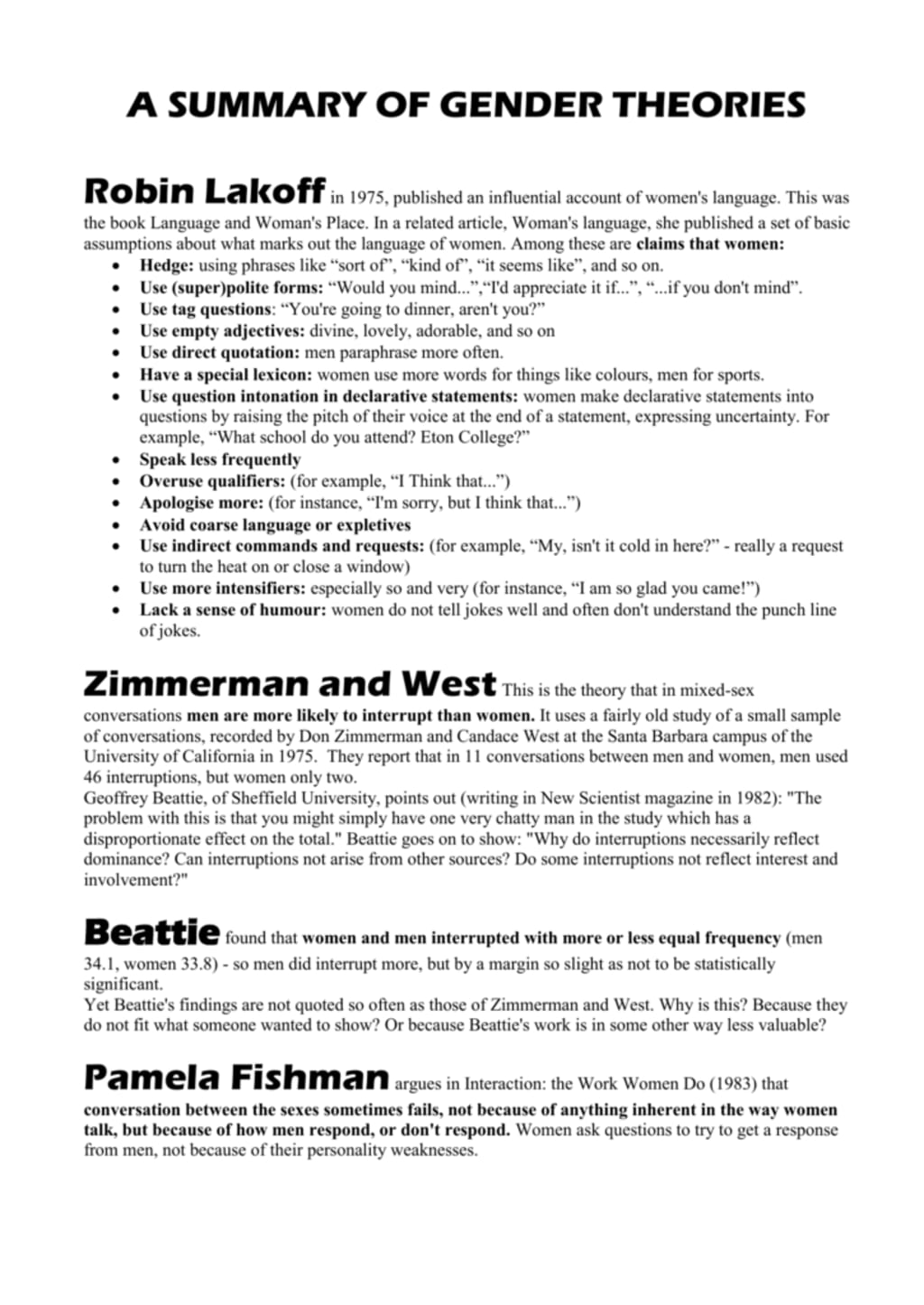

Ford’s linguistic style resonates with Robin Lakoff’s theory of “women’s language” (WL). In 1975, Lakoff published Language and Women’s Place, which included a list of fourteen linguistic characteristics (endnote 4) associated with feminine speech (Cameron & Kulick, 48). These characteristics “reduce the force of utterances which include them,” causing the speaker to “sound less certain, less confident[,] and less authoritative or powerful than she would otherwise;” they index “femininity” because they involve “symbolically minimizing one’s power” (Cameron & Kulick, 48). Although women do not always use WL and women are not the only speakers of WL, Lakoff contends that WL indexes feminine characteristics such as “deference,” “insecurity,” “and a lack of authority” (Cameron & Kulick, 56). For example, WL speakers are more likely to use “proper” language, tending to employ “euphemisms,” “better grammar,” “and fewer colloquialisms” (Cameron & Kulick, 49). When describing the night of her assault, Ford used the term “inebriated” to describe the state of Mr. Kavanagh and Mr. Judge (Washington Post Transcript, 12, 26). While she once described the young men as “visibly drunk” (Washington Post Transcript, 12), she never used conversational words such as “wasted” or “smashed.” Through these careful word choices, Ford avoided coming across as an overbearing woman.

Similarly, WL speakers are known to be “polite” and “indirect” (Cameron & Kulick, 49). Ford did not make straightforward demands; when asked what she desired, she answered with a deferential tone. When Congress members, such as Senator Whitehouse and Senator Blumenthal, inquired whether she wanted an FBI investigation, her responses included:

• “Yes. I feel like it would – I could be more helpful…if that was the case…” (Washington Post Transcript, 42).

• “That would be my preference. I’m not sure if it’s really up to me, but I certainly would feel like I could be more helpful to everyone…”(Washington Post Transcript, 61).

Although she began with “Yes” or “That would be my preference,” Ford did not explicitly state that an FBI investigation is necessary; she strayed from confrontation, referencing how she feels such a step would be helpful. She does not assert her position, which also aligns with how WL speakers’ avoid “commit[ing] themselves to an opinion” (Cameron & Kulick, 49). We see this linguistic practice again when the cross-examiner, Mitchell, asks about the source of Ford’s anxiety and PTSD (Washington Post Transcript, 44-45); Ford is ambivalent. She emphasizes the “etiology of anxiety and PTSD is multifaceted,” portraying her sexual assault as just one “risk factor” (Washington Post Transcript, 44-45). Only when pressed further by Mitchell (after two follow-up questions), she affirms that “nothing as striking as that event” stands out as a risk factor (Washington Post Transcript, 44-45). Although her scientific knowledge contributes to her reluctance, Ford’s extensive elaboration (about six to seven lines of text) on her uncertainty suggests she is unwilling to assert a concrete opinion (Washington Post Transcript, 44-45).

This in mind, it is no surprise that Ford uses “hedges” – phrases that convey a lack of conviction and are common for WL speakers (Cameron & Kulick, 49). She tags variations of “I don’t know” and “I don’t know if I understand” onto many of her statements. When Mitchell questions her, “How do you know there was a conversation,” Ford explains she is “assuming, since it was a social gathering;” at the end of her reply, she adds on, “I don’t know” (Washington Post Transcript, 32). The hedge paints Ford as unconfident and un-authoritative. Such restraint is also found in Ford’s use of nonverbal communication, which is characteristic of WL (Cameron & Kulick, 49). Most notable, we see a reliance on gestural response when Whitehouse inquires, “You specifically asked for an FBI investigation, did you not?” (Washington Post Transcript, 41). Ford replies only with a nod of her head up and down – as if expecting the congressman to continue; her attorneys quickly prompt her to “say something” and then, she adds, “Yes” (Washington Post Transcript, 41). Such a reserved response suggests Ford is afraid of interrupting Whitehouse, adding to her docile, unassertive image.

Many have challenged Lakoff’s theory, which is heteronormative and centered on the linguistic practices of a narrow demographic: cis white middle class English-speaking American women (Cameron & Kulick, 52). Because she practices WL, Ford not only indexes her femininity through speech – she also indexes factors like race and class. Overall, Ford performs her identity as a white middle class woman through a deferential, polite, soft-spoken speech style.

The “Perfect Victim” Reproduces White Patriarchy

Why would performing passivity benefit Ford? Does her use of WL simply exacerbate her powerlessness? Would she not exert greater power if she came across as confident and strong? Not necessarily. Women, particularly privileged women, are often implicated in the reproduction of their gender’s oppression. This is because patriarchy offers women limited avenues for exerting power; when we choose to take one of these avenues, we often reinforce the (white) patriarchal order.

Ochs and Taylor highlight how women, as mothers and wives, are involved in the “everyday” reproduction of a “‘Father knows best’ ideological dynamic” (117). In their dinner table study, middle class women exercised power by performing the “introducer” role (Ochs & Taylor, 103, 116); “[nominating] narrative topics” throughout the meal, they oversaw who spoke, what was spoken about, and when narratives were spoken (Ochs & Taylor, 103). However, this role involved directing the narrative to their husbands – “giving fathers a platform for monitoring and judging wives and children” (Ochs & Taylor, 117). Their exercise of power had “self-destructive” consequences, affirming men as the “arbiters of conduct” and leaving narrators “vulnerable to repeated spousal/paternal criticism” (Ochs & Taylor, 117). Overall, women played a “pivotal role in enacting and socializing” a patriarchal family structure (Ochs & Taylor, 117).

hooks makes a similar point about white women, who are complicit in the reproduction of “white patriarchy” (95). In her analysis, she points out how white women attain power by upholding racism; “maintain[ing] clear separations between their status and that of black women,” white women have safeguarded their role as the ‘rightful’ wives and sexual partners of white men (hooks, 95). Yet, acts of “racial dominance” have been intricately tied to “heterosexism” and sexism – which have meant a “white woman’s status” has been “overdetermined by her relationship to white men” (hooks, 95). In order to get access to the fruits of white supremacy, white women have complied with patriarchal norms (hooks, 95). Performing the role the white patriarchy has assigned them, white women have attained power by reenacting their own oppression and the oppression of Black women.

Within a white supremacist, patriarchal, and classist society, women like Ford can get access to protection and privilege if they uphold hegemonic norms. Ford’s “‘appropriate’ performance of gender” (Cameron & Kulick, 52) increased her chances of being listened to and believed – albeit she may have indirectly reinforced her inferiority and the inferiority of others in the process.

The “Perfect Victim” Gains Power Through “Powerlessness”

Does this mean Ford is a mere puppet of the white patriarchy? Gal reminds us: “domination and power rarely go uncontested” (175). People frequently “parody, subvert, resist,” and “contest” hegemonic norms (Gal, 175, 180). In fact, we demonstrate agency even when we “accommodate positioned and powerful ideological framings” (Gal 180). In often-overlooked ways, women actively negotiate and destabilize patriarchal norms and structures.

For example, Hall shows how phone-sex workers found empowerment by using linguistic strategies associated with WL (Hall 183-209; Cameron & Kulick, 60). Although performing stereotypically feminine identities in the service of men’s sexual desires, the women expressed feeling in control of the calls and superior to their clients; they saw themselves as active agents – they were artists and storytellers (Hall 196-209; Cameron & Kulick, 60). Phone-sex workers were not passive “victims,” but individuals who used misogyny to their advantage. They creatively exploited patriarchal norms, acquiring material benefits by enacting “powerless” speech (Hall, 183, 196-209; Cameron & Kulick, 60). In summary, they made what is deemed “powerless” powerful.

This in mind, how should we judge Ford’s linguistic style? Although her speech indexes “powerlessness” and white middle class femininity, shouldn’t we consider the ways her performance may have been strategic? By accommodating white patriarchal classist norms, did she not improve her chances of getting listened to?

But, What About Liberation?

However, where is the line between complicity and resistance? What happens when white middle class women capitalize on their social status? This essay is not intended to rebuke mothers, wives, phone-sex workers, and, especially not, Ford. Rather, as a white woman who is often perceived as passive and harmless – I wonder how speech styles like Ford’s and mine reproduce systems of domination. When I use my proper, soft-spoken, hyper-polite language to get what I want, I reinstate the stereotypes about my gender while exploiting my white privilege. hooks reminds us that Black women have learned to expect “[betrayal]” from white women (107). Through daily acts such as speech, are privileged white women letting all women down?

Kavanaugh was sworn into the Supreme Court in spite of Ford’s picturesque display of white middle class femininity. This event affirms that male supremacy will not be destroyed through compliance with (white) patriarchal norms. It affirms that there is little freedom to gain when privileged white women use their social position to gain power.

I do not think strategic use of one’s social position is inherently bad. And at times, I think it is necessary. However, if society is to radically transform, I think privileged white women need to become better "allies" to women of color and lower-class woman. To make possible a “sisterhood based on political solidarity” (hooks, 109-110), we must begin by actively unraveling and addressing the ways we are implicated in a racist, classist, male-dominated society. Then, without women to support its structure, the white patriarchy may just start to crumble…

Endnotes

(1) Although white middle class femininity is contextually and historically contingent, I used it here to denote the white middle class femininity I have been socialized to uphold and accept as the “ideal.” This form of femininity involves being educated, passive, restrained, and overall unchallenging to hegemonic norms.

(2) I call Ford “perfect” to denote that who she was and how she performed gave her major advantages within a white supremacist, classist, patriarchal order. Survivors should not have to be “perfect” to be heard – but the ones that are centered by the mainstream, are often “perfect” – i.e. white and middle class (Tambe, 199).

(3) To cite the transcript, I indicate the source (Washington Post) and the page number of the exported PDF document.

(4) Although Dr. Ford exhibited most of Lakoff’s 14 WL characteristics, I focus here on her word choice and sentence structure – which I think most strongly index her deferential demeanor.

References

Ashwini Tamber, 2018. “Reckoning with the Silences of #MeToo” in Feminist Studies 44(1):197-203.

bell hooks, “Holding My Sister’s Hand: Feminist Solidarity” in Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom.

Elinor Ochs & Susan Taylor, “The ‘Father Knows Best’ Dynamic in Dinnertime Narratives” in Gender Articulated, edited by Kira Hall & Mary Bucholtz

Kira Hall, “Lip Service on the Fantasy Lines” in Gender Articulated, edited by Kira Hall & Mary Bucholtz.

Norma Mendoza-Denton, “Pregnant Pauses” in Gender Articulated, edited by Kira Hall & Mary Bucholtz.

The Washington Post, “Kavanaugh Hearing Transcript,” Sept. 27, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/national/wp/2018/09/27/kavanaugh-hearing-transcript/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.07a15dd6e560 .

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.