The Black Panther Party... It's Complicated

History of the Black Panthers

Many citizens of the United States have no idea of the legacy of the Black Panther Party or the contributions they made to society. Many believe that the Black Panther Party was a militant group that was also primarily a gang, that’s a lie. It was a social group designed for the protection and elevation of mostly Black citizens, but was open to everyone. They, and their history, is well… complicated.

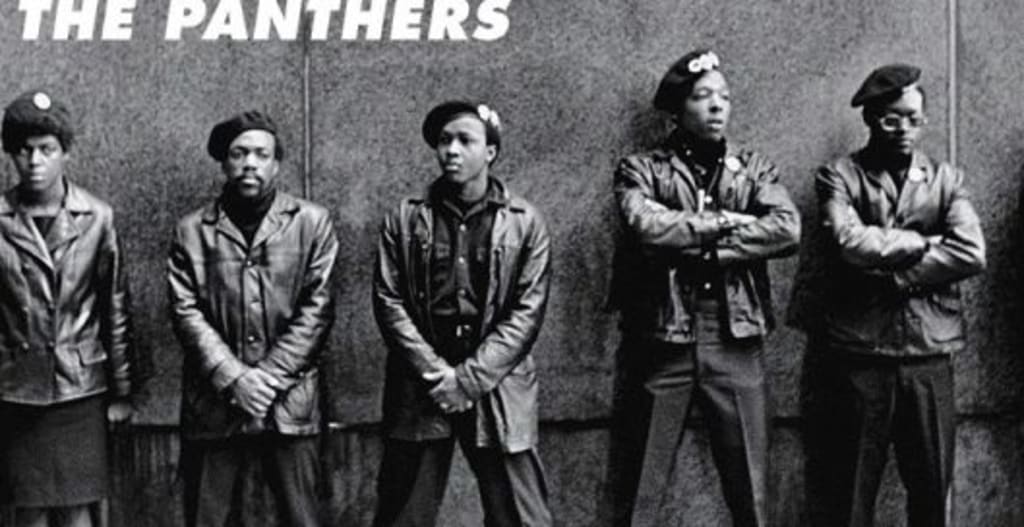

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was considered a revolutionary socialist organization founded by Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton in October 1966.

The party was active in the United States from 1966 until 1982, with international chapters operating in the United Kingdom in the early 1970s, and in Algeria from 1969 until 1972.

At its inception on October 15, 1966, the Black Panther Party's core practice was its armed citizens' patrols to monitor the behavior of police officers of the Oakland Police Department and challenge police brutality in Oakland, California.

In 1969, community social programs became a core activity of party members. The Black Panther Party instituted a variety of community social programs, most extensively the Free Breakfast for Children Programs, and community health clinics to address issues like food injustice. The party enrolled the largest number of members and made the greatest impact in the Oakland-San Francisco Bay Area, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Philadelphia.

Federal Bureau of Investigation Director J. Edgar Hoover called the party "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country", and he supervised an extensive counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO) of surveillance, infiltration, perjury, police harassment, and many other tactics designed to undermine Black Panther leadership, incriminate party members, discredit and criminalize the Party, and drain the organization of resources and manpower. The COINTELPRO program was also accused of assassinating Black Panther members.

Black Panther Party members were involved in many fatal firefights with police including Huey Newton allegedly killing officer John Frey in 1967 and the 1968 Eldridge Cleaver led ambush of Oakland police officers which wounded two officers and killed Black Panther member Bobby Hutton. The party was also involved in many internal conflicts including the murders of Alex Rackley and Betty Van Patter.

Government oppression initially contributed to the party's growth, as killings and arrests of members increased, its support among Blacks and on the broad political left, both of whom valued the Panthers as a powerful force opposed to de facto segregation and the military draft. Black Panther Party membership reached a peak in 1970, with offices in 68 cities and thousands of members, then suffered a series of contractions. After being vilified by the mainstream press, public support for the party waned, and the group became more isolated.

In-fighting among Black Panther leadership, caused largely by the FBI's COINTELPRO operation, led to expulsions and defections that decimated the membership. Popular support for the Party declined further after reports appeared detailing the group's involvement in illegal activities such as drug dealing and extortion schemes directed against Oakland merchants.

In the early 1960s, the insurgent Civil Rights Movement had dismantled the Jim Crow system of racial caste subordination using the tactics of non-violent civil disobedience, and demanding full citizenship rights for Black people. But not much changed in the cities of the North and West. As the wartime jobs which drew much of the black migration fled to the suburbs along with white residents, the black population was concentrated in poor urban ghettos with high unemployment, and substandard housing, mostly excluded from political representation, top universities, and the middle class. Police departments were almost all white. In 1966, only 16 of Oakland's 661 police officers were black representing less than 2.5% of the force.

Insurgent civil rights practices proved incapable of redressing these conditions, and the organizations that had led much of the nonviolent civil disobedience such as SNCC and CORE went into decline. By 1966 a Black Power ferment emerged, consisting largely of young urban Blacks, posing a question the Civil Rights Movement could not answer: how would Black people in America win not only formal citizenship rights, but actual economic and political power? Young Black people in Oakland and other cities developed a rich ferment of study groups and political organizations, and it is out of this ferment that the Black Panther Party emerged.

In late October 1966, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. In formulating a new politics, they drew on their experiences working with a variety of Black Power organizations. Newton and Seale first met in 1962 when they were both students at Merritt College. They joined Donald Warden’s Afro-American Association, where they read widely, debated, and organized in an emergent black nationalist tradition inspired by Malcolm X and others.

Eventually dissatisfied with Warden’s accommodation-ism, they developed a revolutionary anti-imperialist perspective working with more active and militant groups like the Soul Students Advisory Council and the Revolutionary Action Movement. While bringing in a paycheck, jobs running youth service programs at the North Oakland Neighborhood Anti-Poverty Center allowed them to develop a revolutionary nationalist approach to community service, later a key element in the Black Panther Party’s "community survival programs.

Dissatisfied with the failure of these organizations to directly challenge police brutality, Huey and Bobby sought to take matters into their own hands. After the police killed Matthew Johnson, an unarmed young black man in San Francisco, Newton observed the violence that followed. He had an epiphany that would distinguish the Black Panther Party from the multitude of organizations seeking to build Black Power. Newton saw the explosive rebellious anger of the ghetto as a force, and believed that if he could stand up to the police, he could organize that force into political power. Inspired by Robert F. Williams' armed resistance to the KKK and Williams' book Negroes with Guns, Newton studied California gun law until he knew it better than many police officers.

Like the Community Alert Patrol in Los Angeles after the Watts riots, he decided to organize patrols to follow the police around to monitor for incidents of brutality. But with a crucial difference: his patrols would carry loaded guns. Huey and Bobby raised enough money to buy two shotguns by buying bulk quantities of the recently publicized Little Red Book and reselling them to leftist radicals and liberal intellectuals on the Berkeley campus at three times the price. According to Bobby Seale, they would sell the books, make the money, buy the guns, and go on the streets with the guns. We'll protect a mother, protect a brother, and protect the community from the racist cops.

On October 29, 1966, Stokely Carmichael – a leader of SNCC – championed the call for Black Power and came to Berkeley to keynote a Black Power conference. At the time, he was promoting the armed organizing efforts of the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) in Alabama and their use of the Black Panther symbol. Newton and Seale decided to adopt the Black Panther logo and form their own organization called the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. Newton and Seale decided on a uniform of blue shirts, black pants, black leather jackets, and black berets. Sixteen-year-old Bobby Hutton was their first recruit.

The initial tactic of the party utilized contemporary open-carry gun laws to protect Party members when policing the police. This act was done in order to record incidents of police brutality by distantly following police cars around neighborhoods. When confronted by a police officer, Party members cited laws proving they have done nothing wrong and threatened to take to court any officer that violated their constitutional rights. Between the end of 1966 to the start of 1967, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense’s armed police patrols in Oakland black communities attracted a small handful of members. Numbers grew slightly starting in February 1967, when the party provided an armed escort at the San Francisco airport for Betty Shabazz, Malcolm X's widow and keynote speaker for a conference held in his honor.

The Black Panther Party’s focus on militancy was often construed as open hostility, feeding a reputation of violence even though early efforts by the Panthers focused primarily on promoting social issues and the exercise of their legal right to carry arms. The Panthers employed a California law that permitted carrying a loaded rifle or shotgun as long as it was publicly displayed and pointed at no one. Generally this was done while monitoring and observing police behavior in their neighborhoods, with the Panthers arguing that this emphasis on active militancy and openly carrying their weapons was necessary to protect individuals from police violence. For example, chants like "The Revolution has come, it's time to pick up the gun. Off the pigs!", helped create the Panthers' reputation as a violent organization.

The black community of Richmond, California, wanted protection against police brutality. With only three main streets for entering and exiting the neighborhood, it was easy for police to control, contain, and suppress the majority African-American community. On April 1, 1967, a black, unarmed twenty-two-year-old construction worker named Denzil Dowell was shot dead by police in North Richmond. Dowell's family contacted the Black Panther Party for assistance after county officials refused to investigate the case. The Party held rallies in North Richmond that educated the community on armed self-defense and the Denzil Dowell incident. Police seldom interfered at these rallies because every Panther was armed and no laws were broken. The Party's ideals resonated with several community members, who then brought their own guns to the next rallies.

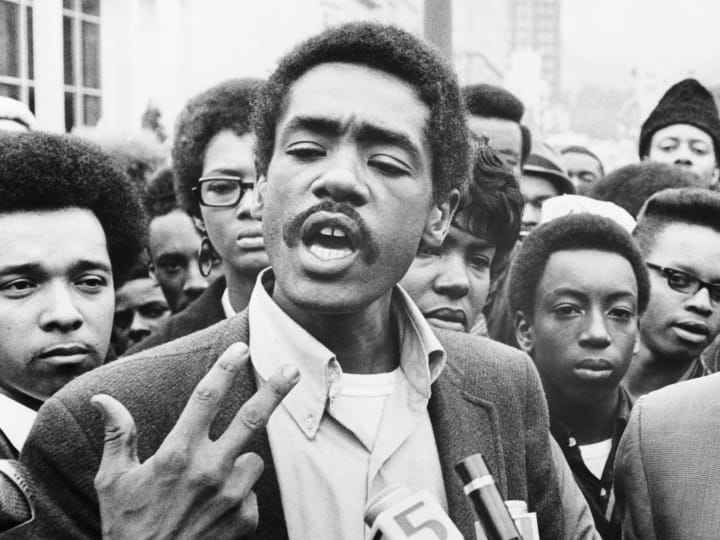

Awareness of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense grew rapidly after their May 2, 1967, protest at the California State Assembly. On May 2, 1967, the California State Assembly Committee on Criminal Procedure was scheduled to convene to discuss what was known as the "Mulford Act", which would make the public carrying of loaded firearms illegal. Eldridge Cleaver and Huey Newton put together a plan to send a group of 26 armed Panthers led by Seale from Oakland to Sacramento to protest the bill. The group entered the assembly carrying their weapons, an incident which was widely publicized, and which prompted police to arrest Seale and five others. The group pleaded guilty to misdemeanor charges of disrupting a legislative session.

In May 1967, the Panthers invaded the State Assembly Chamber in Sacramento, guns in hand, in what appears to have been a publicity stunt. Still, they scared a lot of white people that day. At the time, the Panthers had almost no following. A year later however, their leaders spoke on invitation almost anywhere radicals gathered, and many Whites wore "Honkeys for Huey" buttons, supporting the fight to free Huey Newton, who had been in jail since Oct. 28 1967 on the charge that he killed a policeman .

The Black Panther Party first publicized its original Ten-Point program on May 15, 1967, following the Sacramento action, in the second issue of The Black Panther newspaper. The original ten points of “What We Want Now!" were as follows:

We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.

We want full employment for our people.

We want an end to the robbery by the Capitalists of our Black Community.

We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings.

We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present day society.

We want all Black men to be exempt from military service.

We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people.

We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails.

We want all Black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their Black Communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States.

We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.

In August 1967, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) instructed its program "COINTELPRO" to neutralize what the FBI called Black Nationalist hate groups and other dissident groups. In September 1968, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover described the Black Panthers as the greatest threat to the internal security of the country. By 1969, the Black Panthers and their allies had become primary COINTELPRO targets, singled out in 233 of the 295 authorized Black Nationalist COINTELPRO actions.

The goals of the program were to prevent the unification of militant Black nationalist groups and to weaken the power of their leaders, as well as to discredit the groups to reduce their support and growth. The initial targets included the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Revolutionary Action Movement and the Nation of Islam. Leaders who were targeted included the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, Maxwell Stanford and Elijah Muhammad.

Part of the COINTELPRO actions were directed at creating and exploiting existing rivalries between black nationalist factions. One such attempt was to intensify the degree of animosity between the Black Panthers and the Blackstone Rangers, a Chicago street gang. They sent an anonymous letter to the Ranger's gang leader claiming that the Panthers were threatening his life, a letter whose intent was to induce reprisals against Panther leadership. In Southern California similar actions were taken to exacerbate a gang war between the Black Panther Party and a group called the US Organization. It was alleged that the FBI had sent a provocative letter to the US Organization in an attempt to increase existing antagonism between US and the Panthers.

COINTELPRO also aimed to dismantle the Black Panther Party by targeting the social/community programs they endorsed, one of the most influential being the Free Breakfast for Children Program. The success of the Free Breakfast for Children Program served to shed light on the government's failure to address child poverty and hunger—pointing to the limits of the nation's War on Poverty. The ability of the Party to organize and provide for children more effectively than the U.S. government led the FBI to criticize the program as a means of exposing children to Panther Propaganda. In response to this, as an effort of disassembling the program, Police and Federal Agents regularly harassed and intimidated program participants, supporters, and Party workers and sought to scare away donors and organizations that housed the programs like churches and community centers.

On October 28, 1967, Oakland police officer John Frey was shot to death in an altercation with Huey P. Newton during a traffic stop. In the stop, Newton and backup officer Herbert Heanes also suffered gunshot wounds. Newton was convicted of voluntary manslaughter at trial, but the conviction was later overturned.

At the time, Newton claimed that he had been falsely accused, leading to the "Free Huey" campaign. This incident gained the party even wider recognition by the radical American left. Newton was released after three years, when his conviction was reversed on appeal.

As Newton awaited trial, the Black Panther party's Free Huey campaign developed alliances with numerous individuals, students and anti-war activists, advancing an anti-imperialist political ideology that linked the oppression of antiwar protesters to the oppression of Blacks and Vietnamese. The Free Huey campaign attracted Black Power organizations, New Left groups, and other activist groups such as the Progressive Labor Party, Bob Avakian of the Community for New Politics, and the Red Guard. The Black Panther Party collaborated with the Peace and Freedom Party, which sought to promote a strong antiwar and antiracist politics in opposition to the establishment democratic party. The Black Panther Party provided needed legitimacy to the Peace and Freedom Party's racial politics and in return received invaluable support for the Free Huey campaign.

In 1968 the southern California chapter was founded by Alprentice Bunchy Carter in Los Angeles. Carter was the leader of the Slauson street gang, and many of the LA chapter's early recruits were Slausons.

On April 7, 1968, seventeen-year-old Panther national treasurer Bobby Hutton was killed, and Eldridge Cleaver, Black Panther Party Minister of Information, was wounded in a shootout with the Oakland police. Two police officers were also shot. Although at the time the BPP claimed that the police had ambushed them, several party members later admitted that Cleaver had led the Panther group on a deliberate ambush of the police officers, provoking the shoot-out. Seven other Panthers, including chief of staff David Hilliard, were also arrested. Hutton's death became a rallying issue for Panther supporters.

In 1968, the group shortened its name to the Black Panther Party and sought to focus directly on political action. Members were encouraged to carry guns and to defend themselves against violence. An influx of college students joined the group, which had consisted chiefly of people in the community. This created some tension in the group. Some members were more interested in supporting the Panthers' social programs, while others wanted to maintain a street mentality.

By 1968, the party had expanded into many cities throughout the United States, among them, Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Kansas City, Los Angeles, Newark, New Orleans, New York City, Omaha, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle, Toledo, and Washington, D.C. Peak membership was near 10,000 by 1969, and their newspaper, under the editorial leadership of Eldridge Cleaver, had a circulation of 250,000.

Curtis Austin states that by late 1968, Black Panther Party ideology had evolved to the point where they began to reject black nationalism and became more a "revolutionary internationalist movement":

The Party dropped its wholesale attacks against whites and began to emphasize more of a class analysis of society. Its emphasis on Marxist–Leninist doctrine and its repeated espousal of Maoist statements signaled the group's transition from a revolutionary nationalist to a revolutionary internationalist movement. Every Party member had to study Mao Tse-tung's Little Red Book to advance his or her knowledge of peoples' struggle and the revolutionary process.

Panther slogans and iconography spread. At the 1968 Summer Olympics, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, two American medalists, gave the black power salute during the playing of the American national anthem. The International Olympic Committee banned them from the Olympic Games for life.

Hollywood celebrity Jane Fonda publicly supported Huey Newton and the Black Panthers during the early 1970s. She actually ended up informally adopting the daughter of two Black Panther members. Fonda and other Hollywood celebrities became involved in the Panthers' leftist programs. The Panthers attracted a wide variety of left-wing revolutionaries and political activists, including writer Jean Genet, former Ramparts magazine editor David Horowitz and left-wing lawyer Charles R. Garry, who acted as counsel in the Panthers' many legal battles.

The BPP adopted a "Serve the People" program, which at first involved a free breakfast program for children. By the end of 1968, the BPP had established 38 chapters and branches, claiming more than five thousand members. Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver left the country days before Cleaver was to turn himself in to serve the remainder of a thirteen-year sentence for a 1958 rape conviction. They settled in Algeria.

By 1969, the Black Panther Party newspaper officially stated that men and women are equal and instructed male Panthers to treat female Party members as equals. That same year, Deputy Chairman Fred Hampton of the Illinois chapter conducted a meeting condemning sexism. After 1969, the Party considered sexism counter-revolutionary.

The Black Panthers adopted a womanist ideology in consideration of the unique experiences of Black women, affirming the belief that racism is more oppressive than sexism. Womanism was a mix of black nationalism and the vindication of women, putting race and community struggle before the gender issue. Womanism posited that traditional feminism failed to include race and class struggle in its denunciation of male sexism and was therefore part of white hegemony. In opposition to some feminist viewpoints, womanism promoted a gender role point of view that men are not above women, but hold a different position in the home and community, so men and women must work together for the preservation of African-American culture and community.

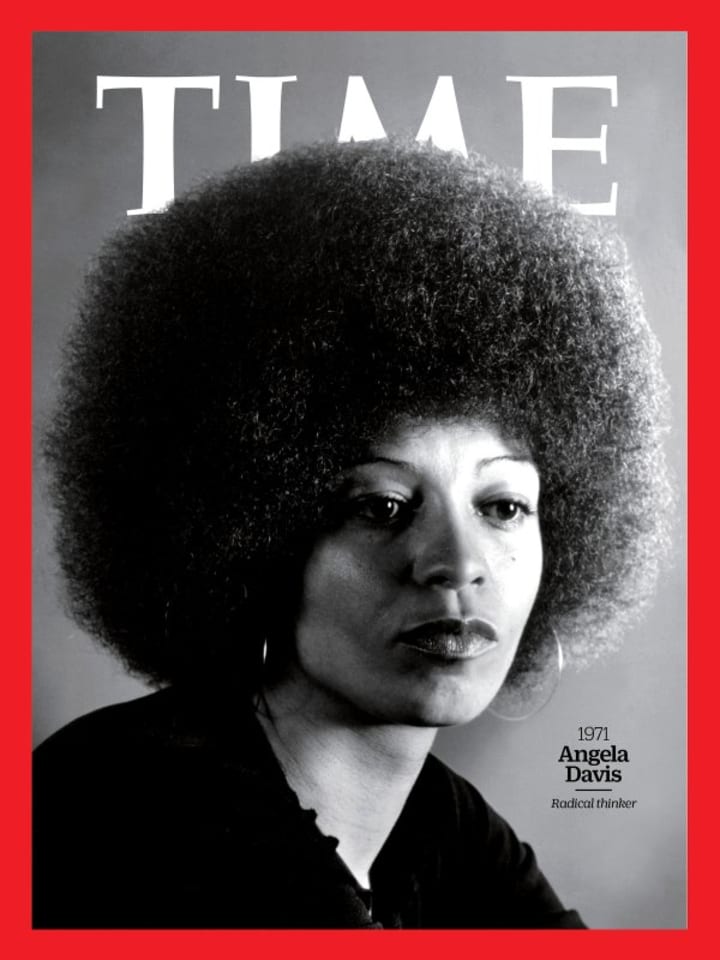

From this point forward, the Black Panther Party newspaper portrayed women as revolutionaries, using the example of party members such as Kathleen Cleaver, Angela Davis and Erika Huggins, all political and intelligent women. The Black Panther Party newspaper often showed women as active participants in the armed self-defense movement, picturing them with children and guns as protectors of the home, the family and the community.

This had direct implications at every level for Black Panther women. From 1968 to the end of its publication in 1982, the head editors of the Black Panther Party newspaper were all women. In 1970, approximately 40% to 70% of Party members were women, and several chapters, like the Des Moines, Iowa, and New Haven, Connecticut, were headed by women.

During the 1970s, recognizing the limited access poor women had to abortion, the Party officially supported women's reproductive rights, including abortion. That same year, the Party condemned and opposed prostitution.

Many women Panthers began to demand childcare in order to be able to fully participate in the organization. The Black Panther Party responded to the women by establishing on-site child development centers in multiple chapters across the United States. Childcare became largely a group activity, the children would be raised collectively during the week. This was following the Panther’s commitment to collectivism and an extension of the African-American extended family tradition. Childcare allowed women Panthers to still be able to embrace motherhood, while at the same time allowing them to fully participate in the Party; allowing women Panthers to not have to make the choice between motherhood and activism.

The Black Panther Party experienced significant problems in several chapters with sexism and gender oppression, particularly in the Oakland chapter where cases of sexual harassment and gender division were common. When Oakland Panthers arrived to bolster the New York City Panther chapter after twenty one New York leaders were incarcerated, they displayed such chauvinistic attitudes towards New York Panther women that they had to be fended off at gunpoint. Some Party leaders thought the fight for gender equality was a threat to men and a distraction from the struggle for racial equality.

In response, the Chicago and New York chapters, among others, established equal gender rights as a priority and tried to eradicate sexist attitudes.

By the time the Black Panther Party disbanded, official policy was to reprimand men who violated the rules of gender equality.

Inspired by Mao Zedong's advice to revolutionaries in The Little Red Book, Newton called on the Panthers to serve the people and to make survival programs a priority within its branches. The most famous of their programs was the Free Breakfast for Children Program, initially run out of an Oakland church.

The Free Breakfast For Children program was especially significant because it served as a space for educating youth about the current condition of the Black community, and the actions that the Party was taking to address that condition. While the children ate their meal, members of the Party taught them liberation lessons consisting of Party messages and Black history. Through this program, the Party was able to influence young minds, and strengthen their ties to communities as well as gain widespread support for their ideologies. The breakfast program became so popular that the Panthers Party claimed to have fed twenty thousand children in the 1968-69 school year.

In 1968, BPP Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver ran for Presidential office on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket. They were a big influence on the White Panther Party, that was tied to the Detroit/Ann Arbor band MC5.

Violent conflict between the Panther chapter in LA and the US Organization, a rival group, resulted in shootings and beatings, and led to the murders of at least four Black Panther Party members. On January 17, 1969, Los Angeles Panther Captain Bunchy Carter and Deputy Minister John Huggins were killed in Campbell Hall on the UCLA campus, in a gun battle with members of the US Organization. Another shootout between the two groups on March 17 led to further injuries. Two more Panthers died.

Paramount to their beliefs regarding the need for individual agency in order to catalyze community change, the BPP strongly supported the education of the masses. As part of their Ten-Point Program which set forth the ideals and goals of the party, they demanded an equitable education for all black people. Number 5 of the "What We Want Now!" section of the program reads: “We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present day society.” In order to ensure that this occurred, the Black Panther Party took the education of their youth into their own hands by first establishing after-school programs and then opening up Liberation Schools in a variety of locations throughout the country which focused their curriculum on Black history, writing skills, and political science.

The first Liberation School was opened by the Richmond Black Panthers in July of 1969 with brunch served and snacks provided to students. Another school was opened in Mt. Vernon New York on July 17th of the subsequent year. These schools were informal in nature and more closely resembled after-school or summer programs. While these campuses were the first to open, the first full-time and longest-running Liberation school was opened in January of 1971 in Oakland in response to the inequitable conditions in the Oakland Unified School District which was ranked one of the lowest scoring districts in California. Named the Intercommunal Youth Institute (IYI), this school, under the directorship of Brenda Bay, and later, Ericka Huggins, enrolled twenty-eight students in its first year, with the majority being the children of Black Panther parents. This number grew to fifty by the 1973-1974 school year. In order to provide full support for Black Panther parents whose time was spent organizing, some of the students and faculty members lived together year around. The school itself was dissimilar to traditional schools in a variety of ways including the fact that students were separated by academic performance rather than age and students were often provided one on one support as the faculty to student ratio was 1:10.

The Panther’s goal in opening Liberation Schools, and specifically the Intercommunal Youth Institute, was to provide students with an education that wasn’t being provided in the white schools, as the public schools in the district employed a eurocentric assimilationist curriculum with little to no attention to black history and culture. While students were provided with traditional courses such as English, Math, and Science, they were also exposed to activities focused on class structure and the prevalence of institutional racism. The overall goal of the school was to instill a sense of revolutionary consciousness in the students. With a strong belief in experiential learning, students had the opportunity to participate in community service projects as well as practice their writing skills by drafting letters to political prisoners associated with the Black Panther Party. Huggins is noted as saying, “I think that the school’s principles came from the socialist principles we tried to live in the Black Panther Party. One of them being critical thinking- that children should learn not what to think but how to think…the school was an expression of the collective wisdom of the people who envisioned it. And it was a living thing that changed every year”. Funding for the Intercommunal Youth Institute was provided through a combination of Black Panther fundraising and community support.

In I974, due to increased interest in enrolling in the school, school officials decided to move to a larger facility and subsequently changed the school’s name to Oakland Community School. During this year, the school graduated its first class. Although the student population continued to grow ranging between 50 and 150 between 1974-1977, the original core values of individualized instruction remained. In September 1977, the school received a special award from Governor Edmund Brown Jr. and the California Legislature for having set the standard for the highest level of elementary education in the state. The school eventually closed in 1982 due to governmental pressure on party leadership which caused insufficient membership and funds to continue running the school.

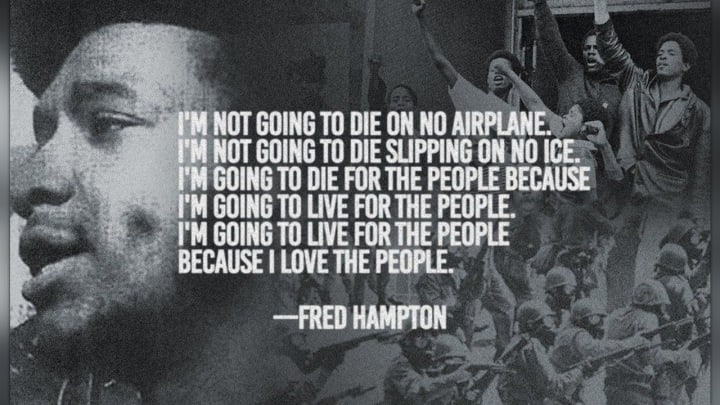

In Chicago, on December 4, 1969, two Panthers were killed when the Chicago Police raided the home of Panther leader Fred Hampton. The raid had been orchestrated by the police in conjunction with the FBI. Hampton was shot and killed, as was Panther guard Mark Clark. A federal investigation reported that only one shot was fired by the Panthers, and police fired at least 80 shots. The only shot fired by the Panthers was from Mark Clark, who appeared to fire a single round determined to be the result of a reflexive death convulsion after he was immediately struck in the chest by shots from the police at the start of the raid.

Hampton was sleeping next to his pregnant fiancée, and was subsequently shot twice in the head at point blank range while unconscious. Coroner reports show that Hampton was drugged with a powerful barbiturate that night, and would have been unable to have been awoken by the sounds of the police raid. His body was then dragged into the hallway. He was 21 years old and unarmed at the time of his death. Seven other Panthers sleeping at the house at the time of the raid were then beaten and seriously wounded, then arrested under charges of aggravated assault and attempted murder of the officers involved in the raid. These charges would later be dropped.

Former FBI agent Wesley Swearingen asserts that the Bureau was guilty of a "plot to murder" the Panthers. Hampton had been slipped the barbiturates which had left him unconscious by William O’Neal, who had been working as an FBI informant. Cook County State's Attorney Edward Hanrahan, his assistant and eight Chicago police officers were indicted by a federal grand jury over the raid, but the charges were later dismissed. In the 1979 civil action, Hampton's family won $1.85 million from the city of Chicago in a wrongful death settlement.

In May 1969, three members of the New Haven chapter tortured and murdered Alex Rackley, a 19-year-old member of the New York chapter, because they suspected him of being a police informant. Three party officers — Warren Kimbro, George Sams Jr., and Lonnie McLucas — later admitted taking part. Sams, who gave the order to shoot Rackley at the murder scene, turned state's evidence and testified that he had received orders personally from Bobby Seale to carry out the execution. Party supporters responded that Sams was himself the informant and an agent provocateur employed by the FBI. The case resulted in the New Haven Black Panther trials of 1970. Kimbro and Sams were convicted of the murder, but the trials of Seale and Ericka Huggins ended with a hung jury, and the prosecution chose not to seek another trial.

Activists from many countries around the globe supported the Panthers and their cause. In Scandinavian countries such as Norway and Finland, for example, left-wing activists organized a tour for Bobby Seale and Masai Hewitt in 1969. At each destination along the tour, the Panthers talked about their goals and the Free Huey campaign. Seale and Hewitt made a stop in Germany as well, gaining support for the Free Huey campaign.

Significant disagreements among the Party's leaders over how to confront ideological differences led to a split within the party. Certain members felt that the Black Panthers should participate in local government and social services, while others encouraged constant conflict with the police. For some of the Party's supporters, the separations among political action, criminal activity, social services, access to power, and grass-roots identity became confusing and contradictory as the Panthers' political momentum was bogged down in the criminal justice system. These and other disagreements led to a split.

Some Panther leaders, such as Huey Newton and David Hilliard, favored a focus on community service coupled with self-defense; others, such as Eldridge Cleaver, embraced a more confrontational strategy. Eldridge Cleaver deepened the schism in the party when he publicly criticized the Party for adopting a reformist rather than revolutionary agenda and called for Hilliard's removal. Cleaver was expelled from the Central Committee but went on to lead a splinter group, the Black Liberation Army, which had previously existed as an underground paramilitary wing of the Party. The split turned violent, as the Newton and Cleaver factions carried out retaliatory assassinations of each other's members, resulting in the deaths of four people.

In late September 1971, Huey P Newton led a delegation to China and stayed for 10 days. At every airport in China, Huey was greeted by thousands of people waving copies of the Little Red Book and displaying signs that said we support the Black Panther Party, down with US imperialism or we support the American people but the Nixon imperialist regime must be overthrown. During the trip the Chinese arranged for him to meet and have dinner with a DPRK ambassador, a Tanzania ambassador, and delegations from both North Vietnam and the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam. Huey was under the impression he was going to meet Mao Zedong, but instead had two meetings with the first Premier of the People's Republic of China Zhou Enlai. One of these meetings also included Mao Zedong's wife Jiang Qing. Huey described China as a free and liberated territory with a socialist government.

In 1972, the party began closing down dozens of chapters and branches all over the country, and bringing members and operations to Oakland. The political arm of the southern California chapter was shut down and its members moved to Oakland, although the underground military arm remained for a time. The underground remnants of the LA chapter, which had emerged from the Slausons street gang, eventually re-emerged as the Crips, a street gang who at first advocated social reform before devolving into racketeering.

The party developed a five-year plan to take over the city of Oakland politically. Bobby Seale ran for mayor, Elaine Brown ran for city council, and other Panthers ran for minor offices. Neither Seale nor Brown were elected. A few Panthers won seats on local government commissions.

Minister of Education Ray Masai Hewitt created the Buddha Samurai, the party's underground security cadre in Oakland. Newton expelled Hewitt from the party later in 1972, but the security cadre remained in operation under the leadership of Flores Forbes.

In 1974, Huey Newton and eight other Panthers were arrested and charged with assault on police officers. Newton went into exile in Cuba to avoid prosecution for the murder of Kathleen Smith, an eighteen-year-old prostitute. Newton was also indicted for pistol-whipping his tailor, Preston Callins. He was ultimately acquitted of assaulting Preston Callins after Callins refused to press charges.

In October 1977 Flores Forbes, the party's assistant chief of staff, led a botched attempt to assassinate Crystal Gray, a key prosecution witness in Newton's upcoming trial who had been present the day of Kathleen Smith's murder. Unbeknownst to the assailants, they attacked the wrong house and the occupant returned fire. During the shootout one of the Panthers, Louis Johnson, was killed and the other two assailants escaped. One of the two surviving assassins, Flores Forbes, fled to Las Vegas with the help of Panther paramedic Nelson Malloy. Fearing that Malloy would discover the truth behind the botched assassination attempt, Newton allegedly ordered a house cleaning, and Malloy was shot and buried alive in the desert. Although permanently paralyzed from the waist down, Malloy recovered from the assault and told police that fellow Panthers Rollin Reid and Allen Lewis were behind his attempted murder. Newton denied any involvement or knowledge and said the events might have been the result of overzealous party members. Newton was ultimately acquitted of the murder of Kathleen Smith, after Crystal Gray's testimony was impeached by her admission that she had smoked marijuana on the night of the murder.

In 1974, as Huey Newton prepared to go into exile in Cuba, he appointed Elaine Brown as the first Chairwoman of the Party. Under Brown's leadership, the Party became involved in organizing for more radical electoral campaigns, including Brown's 1975 unsuccessful run for Oakland City Council. The Party supported Lionel Wilson in his successful election as the first black mayor of Oakland, in exchange for Wilson's assistance in having criminal charges dropped against Party member Flores Forbes, leader of the Buddha Samurai cadre. In addition to changing the Party's direction towards more involvement in the electoral arena, Brown also increased the influence of women Panthers by placing them in more visible roles within the previously male-dominated organization.

Panther leader Elaine Brown hired Betty Van Patter in 1974 as a bookkeeper. Van Patter had previously served as a bookkeeper for Ramparts magazine, and was introduced to the Panther leadership by David Horowitz, who had been Ramparts' editor and a major fundraiser and board member for the Panther school. Later that year, after a dispute with Brown over financial irregularities, Van Patter went missing on December 13, 1974. Some weeks later, her severely beaten corpse was found on a San Francisco Bay beach. There was insufficient evidence for police to charge anyone with van Patter's murder.

In 1977, Newton returned from exile in Cuba, and found that some men in the party were concerned about the increased power delegated to women, who now outnumbered men in the organization. According to Elaine Brown, Newton authorized the disciplining of school administrator Regina Davis as punishment for reprimanding a male coworker. Davis was hospitalized with a broken jaw. Brown said "The beating of Regina would be taken as a clear signal that the words 'Panther' and 'comrade' had taken a gender on gender connotation, denoting an inferiority in the female half of us." Brown resigned from the party and fled to LA.

Although many scholars and activists date the Party's downfall to the period before Brown became the leader, an increasingly smaller group of Panthers continued to exist through the 1970s. By 1980, Panther membership had dwindled to 27, and the Panther-sponsored school closed in 1982 after it became known that Newton was embezzling funds from the school to pay for his drug addiction.

Numerous former Panthers have held elected office in the United States; these include Charles Barron (New York City Council), Nelson Malloy (Winston-Salem City Council), and Bobby Rush (US House of Representatives). Most of these officials hold positive assessments of the BPP's overall contribution to black liberation and American democracy. In 1990, the Chicago City Council passed a resolution declaring Fred Hampton Day in honor of the slain leader. In Winston-Salem in 2012, a large contingent of local officials and community leaders came together to install a historic marker of the local BPP headquarters; State Representative Earline Parmone declared "The Black Panther Party dared to stand up and say, 'We're fed up and we’re not taking it anymore'...Because they had courage, today I stand as … the first African American ever to represent Forsyth County in the state Senate".

In January 2007, a joint California state and Federal task force charged eight men with the August 29, 1971, murder of California police officer Sgt. John Young. The defendants have been identified as former members of the Black Liberation Army. Two have been linked to the Black Panthers. In 1975 a similar case was dismissed when a judge ruled that police gathered evidence through the use of torture. On June 29, 2009, Herman Bell pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter in the death of Sgt. Young. In July 2009, charges were dropped against four of the accused: Ray Boudreaux, Henry W. Jones, Richard Brown and Harold Taylor. Also that month Jalil Muntaquim pleaded no contest to conspiracy to commit voluntary manslaughter becoming the second person to be convicted in this case. Since the 1990s, former Panther chief of staff David Hilliard has offered tours of sites in Oakland that are historically significant to the Black Panther Party.

Various groups and movements have picked names inspired by the Black Panthers:

Assata's Daughters, an all-black activist group in Chicago, was founded in 2015 by Page May; the group is named after Black Panther Assata Shakur and has objectives similar to the Black Panther's 10-Point Program.

Gray Panthers, often used to refer to advocates for the rights of seniors (Gray Panthers in the United States, The Grays – Gray Panthers in Germany).

Polynesian Panthers, an advocacy group for Māori and Pacific Islander people in New Zealand.

Black Panthers, a protest movement that advocates social justice and fights for the rights of Mizrahi Jews in Israel.

White Panthers, used to refer to both the White Panther Party, a far-left, anti-racist, White American political party of the 1970s, as well as the White Panthers UK, an unaffiliated group started by Mick Farren.

The Pink Panthers, used to refer to two LGBT rights organizations.

Dalit Panthers, an Indian social reform movement, which fights against Caste Oppression in Indian Society.

The British Black Panther movement, which flourished in London in the late 1960s and early 1970s, was not affiliated with the American organization although it fought for many of the same rights.

The French Black Dragons, a black antifascist group closely linked to the punk rock and rockabilly scene.

Young Lords

Black Lives Matter

Huey P. Newton Gun Club, a gun club named after the Black Panther Party's founder.

Memphis Black Autonomy Federation.

In April 1977 Panthers were key supporters of the 504 Sit-In, the longest of which was the 25-day occupation of the San Francisco Federal Building by over 120 people with disabilities. Panthers provided daily home-cooked meals and support of the people that proved essential to the protest's success, which in turn inspired a movement that was instrumental in getting the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) passed thirteen years later.

In 1989, a group calling itself the "New Black Panther Party" was formed in Dallas, Texas. Ten years later, the NBPP became home to many former Nation of Islam members when its chairmanship was taken by Khalid Abdul Muhammad.

The Anti-Defamation League and the Southern Poverty Law Center include the New Black Panthers on their lists of designated hate groups.

The Huey Newton Foundation, former chairman and co-founder Bobby Seale, and members of the original Black Panther Party have insisted that this New Black Panther Party is illegitimate and they have strongly objected to it by stating that there is no new Black Panther Party.

Creation and legacy of the Black Panther Party Community Programs

1966 - 1982

1. Alameda County Volunteer Bureau Work Site

2. Benefit Counseling

3. Black Student Alliance

4. Child Development Center

5. Consumer Education Classes

6. Community Facility Use

7. Community Health Classes

8. East Oakland CIL (Center for Independent Living) Branch

9. Community Pantry (Free Food Program)

10. Drug/Alcohol Abuse Awareness Program

11. Drama Classes

12. Disabled Persons Services/Transportation and Attendant

13. Drill Team

14. Employment Referral Service

15. Free Ambulance Program

16. Free Breakfast for Children Programs

17. Free Busing to Prisons Program

18. Free Clothing Program

19. Free Commissary for Prisoners Program

20. Free Dental Program

21. Free Employment Program

22. Free Food Program

23. Free Film Series

24. Free Furniture Program

25. Free Health Clinics

26. Free Housing Cooperative Program

27. Food Cooperative Program

28. Free Optometry Program

29. Community Forum

30. Free Pest Control Program

31. Free Plumbing and Maintenance Program

32. Free Shoe Program

33. GED Classes

34. Geriatric Health Center

35. GYN Clinic

36. Home SAFE Visits

37. Intercommunal Youth Institute (becomes OCS by 1975)

38. Junior and High School Tutorial Program

39. Legal Aid and Education

40. Legal Clinic/Workshops

41. Laney Experimental College Extension Site

42. Legal Referral Service(s)

43. Liberation Schools

44. Martial Arts Program

45. Nutrition Classes

46. Oakland Community Learning Center

47. Outreach Preventative Care

48. Program Development

49. Pediatric Clinic

50. Police patrols

51. Seniors Against a Fearful Environment

52. SAFE Club

53. Sickle Cell Anemia Research Foundation

54. Son of Man Temple (becomes Community Forum by 1976)

55. Sports

56. Senior Switchboard

57. The Black Panther Newspaper

58. Teen Council

59. Teen Program

60. U.C. Berkeley Students Health Program

61. V.D. Preventative Screening & Counseling

62. Visiting Nurses Program

63. WIC (Women Infants, and Children) Program

64. Youth Diversion and Probation Site

65. Youth Training and Development

The Black Panthers Party was an extremely complicated organization that fought for social justice and created sixty-five social programs, of which over forty are now government run programs. Yet the Black Panther Party was considered the greatest threat to the internal security of the country, or if it were today, they would be considered the greatest threat to national security. They were hunted, murdered, chased out of the country, jailed and encouraged to walk away from social justice, yet there is no solution for the Klu Klux Klan, which has been in existence for over 100 years and whose only contribution to society is to murder citizens and have lawmakers that create unjust and dehumanizing laws, adding nothing beneficial to society.

About the Creator

Glenda Davis

The purpose of this blog will be to discuss race relations, learn history and hopefully help us all to be more patient, understanding, emphatic.

I am a 59 year old Black woman, a veteran Sargent of the United States Air Force and a retiree.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.